Ottoman ironclad Muin-i Zafer

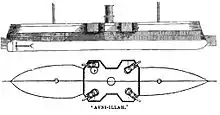

Muin-i Zafer (Ottoman Turkish: Aid to Triumph) was the second of two Avnillah-class casemate ships built for the Ottoman Navy in the late 1860s. The ship was laid down in 1868, launched in 1869, and she was commissioned into the fleet the following year. A central battery ship, she was armed with a battery of four 228 mm (9 in) guns in a central casemate, and was capable of a top speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).

.tiff.jpg.webp) Muin-i Zafer in Constantinople, sometime before 1894 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Muin-i Zafer |

| Namesake | "Aid to Triumph" |

| Ordered | 1867 |

| Builder | Samuda Brothers, Cubitt Town |

| Laid down | 1868 |

| Launched | June 1869 |

| Commissioned | 1870 |

| Decommissioned | 1932 |

| Fate | Broken up, 1934 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Avnillah-class ironclad |

| Displacement | 2,362 metric tons (2,325 long tons) |

| Length | 68.9 m (226 ft 1 in) (lpp) |

| Beam | 10.9 m (35 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 5 m (16 ft 5 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament | 4 × 228 mm (9 in) guns |

| Armor | |

Muin-i Zafer saw action during the Russo-Turkish War in 1877–1878, where she supported Ottoman forces in the Caucasus. After the war, she was placed in reserve and allowed to deteriorate; by the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish War in 1897, she was in unserviceable condition. Muin-i Zafer was reconstruction by Gio. Ansaldo & C. after the war, and was later converted for secondary duties, including as a training ship in 1913, a barracks ship in 1920, and a depot ship for submarines in 1928. The ship was ultimately decommissioned in 1932 and broken up in 1934.

Design

Muin-i Zafer was 68.9 m (226 ft 1 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 10.9 m (35 ft 9 in) and a draft of 5 m (16 ft 5 in). The hull was constructed with iron, incorporated a partial double bottom, and displaced 2,362 metric tons (2,325 long tons) normally and 1,399 t (1,377 long tons) BOM. She had a crew of 15 officers and 130 enlisted men.[1][2]

The ship was powered by a single horizontal compound engine which drove one screw propeller. Steam was provided by four coal-fired box boilers that were trunked into a single funnel amidships. The engine was rated at 2,200 indicated horsepower (1,600 kW) and produced a top speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), though by 1877 she was only capable of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Decades of poor maintenance had reduced the ship's speed to 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) by 1892. Muin-i Zafer carried 220 t (220 long tons; 240 short tons) of coal. A supplementary brigantine rig was also fitted.[1][2]

The ship was armed with a battery of four 228 mm (9 in) muzzle loading guns mounted in a central, armored casemate, two guns per side. The guns were positioned so as to allow any two to fire directly ahead, astern, or to either broadside. The ship's armored belt was 127 to 152 mm (5 to 6 in) thick, with the thicker portion above the waterline and the thinner below. The belt extended 0.6 m (2 ft) above the line and 1.2 m (4 ft) below, and was capped with 76 mm (3 in) thick transverse bulkhead at either end. The casemate had heavy armor protection, with the gun battery protected by 152 mm of iron plating.[1][2]

Service history

Muin-i Zafer, meaning "Aid to Triumph",[3] was ordered in 1867 from the Samuda Brothers shipyard in Cubitt Town, London. The keel for the ship was laid down in 1868 and she was launched in June 1869. She conducted sea trials in 1870 and was commissioned into the Ottoman fleet later that year.[2] Upon completion, Muin-i Zafer and the other ironclads then being built in Britain and France were sent to Crete to assist in stabilizing the island in the aftermath of the Cretan Revolt of 1866–1869. During this period, the Ottoman fleet, under Hobart Pasha, remained largely inactive, with training confined to reading translated British instruction manuals.[4] Muin-i Zafer was assigned to the II Squadron of the Asiatic Fleet, along with her sister ship Avnillah and the ironclads Hifz-ur Rahman and Lütf-ü Celil.[5] Early in the ship's career, the Ottoman ironclad fleet was activated every summer for short cruises from the Golden Horn to the Bosporus to ensure their propulsion systems were in operable condition.[6]

Russo-Turkish War

The Ottoman fleet began mobilizing in September 1876 to prepare for a conflict with Russia, as tensions with the country had been growing for several years, an insurrection had begun in Ottoman Bosnia in mid-1875, and Serbia had declared war on the Ottoman Empire in July 1876. In December 1876, Muin-i Zafer and her sister ship Avnillah were transferred to Batumi owing to the increasingly active Russian naval forces in the area. The Russo-Turkish War began on 24 April 1877 with a Russian declaration of war.[7] Muin-i Zafer spent the war in the Black Sea squadron, with the bulk of the Ottoman ironclad fleet.[8] The eight ironclads of the Ottoman fleet in the Black Sea, commanded by Hobart Pasha, was vastly superior to the Russian Black Sea Fleet; the only ironclads the Russians possessed there were Vitse-admiral Popov and Novgorod, circular vessels that had proved to be useless in service.[9]

The presence of the fleet did force the Russians to keep two corps in reserve for coastal defense, but the Ottoman high command failed to make use of its naval superiority in a more meaningful way, particularly to hinder the Russian advance into the Balkans. Hobart Pasha took the fleet to the eastern Black Sea, where he was able to make a more aggressive use of it to support the Ottoman forces battling the Russians in the Caucasus. The fleet bombarded Poti and assisted in the defense of Batumi.[10] On 14 May 1877, an Ottoman squadron consisting of Muin-i Zafer, Avnillah, Necm-i Şevket, Feth-i Bülend, Mukaddeme-i Hayir, and Iclaliye bombarded Russian positions around the Black Sea port of Sokhumi before landing infantry and arming the local populace to start an uprising against the Russians. The Ottomans captured Sokhumi two days later.[11][12] By June, Muin-i Zafer had been transferred to Sulina at the mouth of the Danube, along with the ironclads Hifz-ur Rahman and Asar-i Şevket. The ships were tasked with defending the seaward approach to the port, supporting three coastal fortifications.[13]

Later career

After the end of the war in 1878, the ship was laid up in Constantinople;[2] she did not see further activity for the next twenty years. The annual summer cruises to the Bosporus ended after the war.[14] During this period, the ship was modernized slightly. In 1882, a pair of 87 mm (3.4 in) breech-loading guns manufactured by Krupp were added. At some point, she also received new Scotch marine boilers, and her brigantine rig was removed, with heavy military masts installed in its place. The Ottomans planned to further strengthen the ship's armament with a pair of 63 mm (2.5 in) Krupp guns, two 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon, two 25.4 mm (1 in) guns, also manufactured by Hotchkiss, and a 450 mm (18 in) torpedo tube, but the plan came to nothing.[1][15]

By the mid-1880s, the Ottoman ironclad fleet was in poor condition, and Muin-i Zafer was unable to go to sea. Many of the ships' engines were unusable, having seized up from rust, and their hulls were badly fouled. The British naval attache to the Ottoman Empire at the time estimated that the Imperial Arsenal would take six months to get just five of the ironclads ready to go to sea. Throughout this period, the ship's crew was limited to about one-third the normal figure. During a period of tension with Greece in 1886, the fleet was brought to full crews and the ships were prepared to go to sea, but none actually left the Golden Horn, and they were quickly laid up again. By that time, most of the ships were capable of little more than 4 to 6 knots (7.4 to 11.1 km/h; 4.6 to 6.9 mph).[16]

At the start of the Greco-Turkish War in February 1897, the Ottomans inspected the fleet and found that almost all of the vessels, including Muin-i Zafer, to be completely unfit for combat against the Greek Navy. Many of the ships had rotted hulls and their crews are poorly trained. Through April and May, the Ottoman fleet made several sorties into the Aegean Sea in an attempt to raise morale among the ships' crews, though the Ottomans had no intention of attacking Greek forces. The condition of the Ottoman fleet could not be concealed from foreign observers, which proved to be an embarrassment for the government and finally forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to authorize a modernization program, which recommended that the ironclads be modernized in foreign shipyards. Following a lengthy process of negotiations, Krupp received the contract to rebuild Muin-i Zafer on 11 August 1900, along with several other warships. By December 1902, however, Krupp withdrew from the deal and the Italian firm Gio. Ansaldo & C. took over the project.[17] By 1906, the work was completed. Her old muzzle-loading guns were replaced with new 150 mm (5.9 in) Krupp 40-caliber guns, and a new light battery consisting of six 75 mm (3 in) quick-firing (QF) Krupp guns, ten 57 mm (2.2 in) QF Krupp guns, and two 47 mm (1.9 in) QF Krupp guns.[15]

Muin-i Zafer was reduced to a stationary ship in İzmir in 1910, at which point her armament was reduced to just two of the 75 mm guns and four 57 mm guns.[18] In September 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire, initiating the Italo-Turkish War. At the start of the war, Muin-i Zafer was stationed as a guard ship in Beirut.[19] She left shortly after the onset of hostilities, however, and on 30 September arrived in Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal. There, she was disarmed and her guns were taken ashore to strengthen the local defenses.[20] By the start of the First Balkan War in October 1912, Muin-i Zafer had been moved back to İzmir.[5]In 1913, she became a torpedo training ship based in Constantinople. The ship was converted into a floating barracks in 1920 stationed in İzmit. In 1928, the vessel was converted again, into a depot ship for submarines at Erdek. She served in that capacity for four years before being decommissioned in 1932; she was broken up for scrap in 1934.[2]

Notes

- Lyon, p. 390.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 138.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 198.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 3, 5.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 194.

- Sturton, p. 138.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 5.

- Greene & Massignani, p. 358.

- Barry, pp. 97–102.

- Barry, pp. 114–115, 190.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 6.

- Greene & Massignani, p. 360.

- Wilson, pp. 289, 295.

- Sturton, pp. 138, 144.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 137.

- Sturton, p. 144.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 8–11.

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 137–138.

- Beehler, p. 12.

- Beehler, pp. 25–26.

References

- Barry, Quintin (2012). War in the East: A Military History of the Russo-Turkish War 1877–78. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-11-3.

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Combined Publishing. ISBN 978-0-938289-58-6.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Turkey". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 388–394. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Sturton, Ian. "Through British Eyes: Constantinople Dockyard, the Ottoman Navy, and the Last Ironclad, 1876–1909". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. 57 (2). ISSN 0043-0374.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.