Ouranosaurus

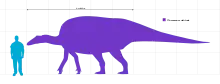

Ouranosaurus is a genus of herbivorous basal hadrosauriform dinosaur that lived during the Aptian stage of the Early Cretaceous of modern-day Niger and Cameroon. Ouranosaurus measured about 7–8.3 metres (23–27 ft) long and weighed 2.2 metric tons (2.4 short tons). Two rather complete fossils were found in the Elrhaz Formation, Gadoufaoua deposits, Agadez, Niger, in 1965 and 1970, with a third indeterminate specimen known from the Koum Formation of Cameroon. The animal was named in 1976 by French paleontologist Philippe Taquet; the type species being Ouranosaurus nigeriensis. The generic name is a combination of ourane, a word with multiple meanings ("an Arabic name that signifies valor, courage, recklessness"; the Tuareg name of the desert monitor given by the Tuareg Berbers of Niger & Algeria), and sauros, the Greek word for lizard. The specific epithet nigeriensis alludes to Niger, its country of discovery (in Latin, the adjectival suffix -iensis means "originating from"). And so, Ouranosaurus nigeriensis could be interpreted as "brave lizard originating from Niger".[1]

| Ouranosaurus Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted paratype skeleton, Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia 3714 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Styracosterna |

| Clade: | †Hadrosauriformes |

| Genus: | †Ouranosaurus Taquet, 1976 |

| Species: | †O. nigeriensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 | |

Discovery and naming

Five French palaeontological expeditions were undertaken in the Gadoufaoua region of the Sahara Desert in Niger between 1965 and 1972 and led by French palaeontologist Philippe Taquet.[1] These deposits come from GAD 5, a layer in the upper Elrhaz Formation of the Tégama Group, which was deposited during the Aptian stage of the Early Cretaceous.[2] On the first expedition, lasting from January–February 1965, eight iguanodontian specimens were discovered at the "niveau des Innocents" site, east of the Emechedoui wells. An additional two skeletons were discovered 7 km (4.3 mi) southeast of Elrhaz in the "Camp des deux Arbres" locality, which were given the field numbers GDF 300 and GDI 381. Both were collected in the February–April 1996 expedition, the former including a nearly complete but scattered skeleton, and the latter a skeleton that was two-thirds preserved.[1][3] The skeletons then in 1967 were brought to the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle of Paris, where they were prepared. GDF 381 was recategorized with the number MNHN GDF 1700 and then later described in 1999 as the holotype of the new taxon Lurdusaurus arenatus.[3] While the third expedition did not turn up additional iguanodontian material, the fourth in January–March 1970 uncovered a nearly complete and partially articulated skeleton lacking the skull, 4 km (2.5 mi) south of the "niveau des Innocents" site, and was also given the field number GDF 381. This specimen was collected and taken to the MNHN by the fifth expedition in 1972.[1][3] Following a subsequent Italian-French expedition led by Taquet and Italian palaeontologist Giancarlo Ligabue that turned up a potential additional iguanodontian specimen, Ligabue offered to donate the nearly complete specimen and a skull of Sarcosuchus to the Municipality of Venice, which accepted the offer and subsequently mounted the skeleton in 1975 at the Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia.[3]

Taquet formally described the two mostly-complete specimens MNHN GDF 300 and MNHN GDF 381 from the first and fourth expeditions as Ouranosaurus nigeriensis in 1976, along with a referred coracoid and femur that bore the numbers MNHN GDF 301 and MNHN GDF 302 respectively. MNHN GDF 300 was made the holotype, and was the primary specimen described, including a semi-articulated skull lacking the left maxilla, right quadratojugal and the articulars, almost the entire vertebral column, forelimbs lacking a few hand bones, and most of the right hindlimb and a few bones of the left.[1] Additional description for bones unpreserved in the holotype was based on Taquet's MNHN GDF 381, which was not mentioned as having been sent to Venice and renumbered as MSNVE 3714, although this was confirmed by Italian palaeontologist Filippo Bertozzo and colleagues in 2017. The holotype itself was returned to Niger after being described and having its bones cast and mounted, and is now on display at the Musée National Boubou Hama in Niamey.[3] The generic name Ouranosaurus carries a double meaning, it is both taken from Arabic meaning "valour", "bravery " or "recklessness" and also from the local Tuareg language of Niger where it is the name they call the desert monitor. The specific name refers to Niger, the country of discovery. Taquet had used the name "Ouranosaurus nigeriensis" previously, first in a public presentation of the skeleton MNHN GDF 300 in July 1972, then later in September 1972 in a news article and again in December 1972 in a book; only the book bore any images associated with the name, and none of the earlier mentions had a diagnosis to make the name valid.[1]

Description

Ouranosaurus was a relatively large iguanodontian, measuring 7–8.3 metres (23–27 feet) long and weighing 2.2 tonnes (2.4 short tons).[1][4] The holotype and paratype specimens were suggested to belong to subadults by Bertozzo et al. in 2017, although they would have been close to adult size. MSNVE 3714 is 6.5 m (21 ft) long as mounted, although a few caudals are missing, and is roughly 90% the length of the holotype, which would be 7.22 m (23.7 ft) long. The variation between the sizes fits within the range of variation between adult individuals of Iguanodon, so there is a chance that the larger holotype and smaller paratype were same ontogenetic stage.[3]

Skull

The skull of Ouranosaurus is 67.0 cm (26.4 in) long. It was rather low, being 24.4 cm (9.6 in) wide and only 26.0 cm (10.2 in) tall. The top of the skull was flat, the highest point being just in front of the orbits and sloping down towards both the rear of the skull and the tip of the snout.[1] This makes Ouranosaurus have the most elongate skull of any non-hadrosaurid, the length being 3.8 times the maximum height, although the skull is proportionally wider than related Mantellisaurus.[3]

Bones of the snout are more loosely articulated with each other than the bones of the posterior skull. The premaxillae are 46.0 cm (18.1 in) long, with very deep external nares as in other iguanodontians. Anteriorly, the premaxillae flare gently laterally into a rugose surface for a beak, like other iguanodontians, although dissimilar from Iguanodon and similar to hadrosaurids the nares are entirely visible from above. Neither premaxilla bears any teeth, although the very anterior tip has "pseudo-teeth" formed by multiple denticles on the margin of the bone.[1] Only the right maxilla of Ouranosaurus is known. although it is well preserved forming a triangle 28.0 cm (11.0 in) long and 11.7 cm (4.6 in) tall, much taller proportionally than Iguanodon. The maxilla bears faces for articulation with the premaxilla in front, lacrimal above, ectopterygoid, vomer, palatine and possibly pterygoid internally, and jugal to the rear. The lacrimal process is the highest point of the maxilla, and behind this process is a smooth and curved margin for the antorbital fenestra, which is bounded by the maxilla in front and below, lacrimal above, and jugal behind. The jugal overlaps only the posterior end of the maxilla, which is unlike hadrosaurids where there is more overlap.[1] The dental edge of the maxilla is slightly arced, and above the toothrow is a shallow depression bearing nutrient foramina, also known as the buccal emargination that is diagnostic of Ornithischia.[1][5] 20 teeth are preserved in the maxilla, although the anterior end of the toothrow is broken and Taquet (1976) predicted the total number to be 22.[1]

Many of the central bones of the skull are the same form as those of hadrosaurids or related iguanodontians like Iguanodon and Mantellisaurus. The jugal below and behind the orbit bears the same shape as in hadrosaurids, with a high rear process, and articulated with the quadratojugal and quadrate that are also very similar to more derived taxa. As in other ornithopods, the postorbital is a tri-radiate bone surrounding sides of the orbit, infratemporal fenestra and supratemporal fenestra. Contact between the postorbital and the parietal excludes the flattened and wide frontals from the supratemporal fenestra. In Ouranosaurus and related taxa the prefrontals are small, and articulates with the broadened and textured lacrimal. Only a single supraorbital was present in Ouranosaurus, which projects into the orbit above the eye. The nasal bones of Ouranosaurus are unique among ornithischians. The bones are unfused suggesting mobility, and at their ends on the top of the skull are rounded domes, which were described by Taquet (1976) as distinct and rugose "nasal protuberances".[1]

The snout was toothless and covered in a horny sheath during life, forming a very wide beak together with a comparable sheath on the short predentary bone at the extreme front of the lower jaws. However, after a rather large diastema with the beak, there were large batteries of cheek teeth on the sides of the jaws: the gaps between the teeth crowns were filled by the points of a second generation of replacement teeth, the whole forming a continuous surface. Contrary to the situation with some related species, a third generation of erupted teeth was lacking. There were twenty-two tooth positions in both lower and upper jaw, for a total of eighty-eight.

Postcranial skeleton

The most conspicuous feature of Ouranosaurus is a large "sail" on its back, supported by long, wide, neural spines, that spanned its entire rump and tail, resembling that of Spinosaurus, a well-known meat-eating dinosaur also known from northern Africa.[6] These tall neural spines did not closely resemble those of sail-backs such as Dimetrodon of the Permian Period. The supporting spines in a sailback become thinner distally, whereas in Ouranosaurus the spines actually become thicker distally and flatten. The posterior spines were also bound together by ossified tendons, which stiffened the back. Finally, the spine length peaks over the forelimbs.

The first four dorsal vertebrae are unknown; the fifth already bears a 32-centimetre-long spine (1.05 ft) that is pointed and slightly hooked; Taquet presumed it might have anchored a tendon to support the neck or skull. The tenth, eleventh and twelfth spines are the longest, at about 63 cm (25 in). The last dorsal spine, the seventeenth, has a grooved posterior edge, in which the anterior corner of the lower spine of the first sacral vertebra is locked. The spines over the six sacral vertebrae are markedly lower, but those of the tail base again longer; towards the end of the tail the spines gradually shorten.

The dorsal "sail" is usually explained as either functioning as a system for thermoregulation or a display structure. An alternative hypothesis is that the back might have carried a hump consisting of muscle tissue or fat, resembling that of a bison or camel, rather than a sail. It could have been used for energy storage to survive a lean season.[7]

The axial column consisted of eleven neck vertebrae, seventeen dorsal vertebrae, six sacral vertebrae and forty tail vertebrae. The tail was relatively short.

The front limbs were rather long with 55% of the length of the hind limbs. A quadrupedal stance would have been possible. The humerus was very straight. The hand was lightly built, short and broad. On each hand Ouranosaurus bore a thumb claw or spike that was much smaller than that of the earlier Iguanodon. The second and third digits were broad and hoof-like, and anatomically were good for walking. To support the walking hypothesis, the wrist was large and its component bones fused together to prevent its dislocation. The last digit (number 5) was long. In related species the fifth finger is presumed to have been prehensile: used for picking food like leaves and twigs or to help lower the food by lowering branch to a manageable height. Taquet assumed that with Ouranosaurus this function had been lost because the fifth metacarpal, reduced to a spur, could no longer be directed sideways.

The hindlimbs were large and robust to accommodate the weight of the body and strong enough to allow a bipedal walk. The femur was slightly longer than the tibia. This may indicate that the legs were used as pillars, and not for sprinting. Taquet concluded that Ouranosaurus was not a good runner because the fourth trochanter, the attachment point for the large retractor muscles connected to the tail base, was weakly developed. The foot was narrow with only three toes and relatively long.

In the pelvis, the prepubis was very large, rounded and directed obliquely upwards.

Classification

Taquet originally assigned Ouranosaurus to the Iguanodontidae, within the larger Iguanodontia. However, although it shares some similarities with Iguanodon (such as a thumb spike), Ouranosaurus is no longer usually placed in the iguanodontid family, a grouping that is now generally considered paraphyletic, a series of subsequent offshoots from the main stem-line of iguandontian evolution. It is instead placed in the clade Hadrosauriformes, closely related to the Hadrosauroidea, which contains the Hadrosauridae (also known as "duck-billed dinosaurs") and their closest relatives. Ouranosaurus appears to represent an early specialized branch in this group, showing in some traits independent convergence with the hadrosaurids. It is thus a basal hadrosauriform.

The simplified cladogram below follows an analysis by Andrew McDonald and colleagues, published in November 2010 with information from McDonald, 2011.[8][9]

| Iguanodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Diet

The jaws were apparently operated by relatively weak muscles. Ouranosaurus had only small temporal openings behind the eyes, from which the larger capiti-mandibularis muscle was attached to the coronoid process on the lower jaw bone. Small rounded horns in front of its eyes made Ouranosaurus the only known horned ornithopod. The back of the skull was rather narrow and could not compensate for the lack of a greater area of attachment for the jaw muscle, that the openings normally would provide, allowing for more power and a stronger bite. A lesser muscle, the musculus depressor mandibulae, used to open the lower jaws, was located at the back of the skull and was connected to a strongly projecting, broad and anteriorly oblique processus paroccipitalis. Ouranosaurus probably used its teeth to chew up tough plant food. A diet has been suggested of leaves, fruit, and seeds as the chewing would allow to free more energy from high quality food;[6] the wide beak on the other hand indicates a specialisation in eating large amounts of low quality fodder. Ouranosaurus lived in a river delta.

Histology

Ouranosaurus bears more similarities to other derived iguanodonts than more basal ornithopods. Remodeling is present in the subadult paratype, and high vascular density and circumferential arrangement of the microstructure suggests fast growth. Faster growth occurs in the same phylogenetic groups as higher body size, although their relationship is unclear. Ouranosaurus is a similar size to more basal Tenontosaurus which has slow growth, so either faster growth is caused by body size or Tenontosaurus is the maximum size of an ornithopod with a slow growth rate.[3]

Paleoecology

Ouranosaurus is known from the Elrhaz Formation of the Tegama Group in an area called Gadoufaoua, located in Niger. Only two mostly complete skeletons and up to 3 additional individuals have been found.[3] The Elrhaz Formation consists mainly of fluvial sandstones with low relief, much of which is obscured by sand dunes.[10] The sediments are coarse- to medium-grained, with almost no fine-grained horizons.[11] Ouranosaurus is from the upper portion of the formation, probably Aptian in age.[1] It likely lived in habitats dominated by inland floodplains (a riparian zone).[11]

After the iguanodontian Lurdusaurus, Nigersaurus was the most numerous megaherbivore.[11] Other herbivores from the same formation include Ouranosaurus, Elrhazosaurus, and an unnamed titanosaur. It also lived alongside the theropods Kryptops, Suchomimus, Eocarcharia, Carcharodontosaurus, and Afromimus. Crocodylomorphs like Sarcosuchus, Anatosuchus, Araripesuchus, and Stolokrosuchus also lived there. In addition, remains of a pterosaur, chelonians, fish, a hybodont shark, and freshwater bivalves have been found.[10] Grass did not evolve until the late Cretaceous.[11]

References

- Taquet, P. (1976). "Géologie et Paléontologie du Gisement de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger)" (PDF). Cahiers de Paléontologie. Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris: 1–191. ISBN 2-222-02018-2.

- Taquet, P. (1970). "Sur le gisement de Dinosauriens et de Crocodiliens de Gadoufaoua (République du Niger)" (PDF). Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série D. 271: 38–40.

- Bertozzo, F.; Dalla Vechia, F.M.; Fabbri, M. (2017). "The Venice specimen of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda)". PeerJ. 5: e3403. doi:10.7717/peerj.3403. PMC 5480399. PMID 28649466.

- Paul, G.S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. pp. 292. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- Butler, R.J.; Upchurch, P.; Norman, D.B. (2008). "The phylogeny of ornithischian dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002271. S2CID 86728076.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 144. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Bailey, J.B. (1997). "Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?". Journal of Paleontology. 71 (6): 1124–1146. doi:10.1017/S0022336000036076.

- McDonald, A.T.; Kirkland, J.I.; DeBlieux, D.D.; Madsen, S.K.; Cavin, J.; Milner, A.R.C.; Panzarin, L. (2010). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "New Basal Iguanodontians from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e14075. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514075M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014075. PMC 2989904. PMID 21124919.

- Andrew T. McDonald (2011). "The taxonomy of species assigned to Camptosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2783: 52–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2783.1.4.

- Sereno, P. C.; Brusatte, S. L. (2008). "Basal abelisaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (1): 15–46. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0102.

- Sereno, P. C.; Wilson, J. A.; Witmer, L. M.; Whitlock, J. A.; Maga, A.; Ide, O.; Rowe, T. A. (2007). "Structural extremes in a Cretaceous dinosaur". PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1230. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1230S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001230. PMC 2077925. PMID 18030355.

Bibliography

- Ingrid Cranfield, ed. (2000). Dinosaurs and other Prehistoric Creatures. Salamander Books. pp. 152–154.

- Richardson, Hazel (2003). Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals. Smithsonian Handbooks. p. 108.

- Dixon, Dougal (2006). The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. Hermes House.

- Cox, Barry; Colin Harrison; R.J.G. Savage; Brian Gardiner (1999). The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684864112.

External links

- Ouranosaurus on Nature

- Ouranosaurus (with picture)