Tsintaosaurus

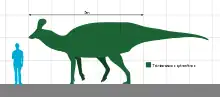

Tsintaosaurus (/sɪntaʊˈsɔːrəs/; meaning "Qingdao lizard", after the old transliteration "Tsingtao"[2]) is a genus of hadrosaurid dinosaur from China. It was about 10 metres (33 ft) long and weighed 4 tonnes (4.4 short tons).[3] The type species is Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus, first described by Chinese paleontologist C. C. Young in 1958.

| Tsintaosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype skull with broken crest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Tsintaosaurini |

| Genus: | †Tsintaosaurus Young, 1958[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus Young, 1958[1] | |

As a hadrosaur, Tsintaosaurus had the characteristic 'duck bill' snout and a battery of powerful teeth which it used to chew vegetation. It usually walked on all fours, but could rear up on its hind legs to scout for predators and flee when it spotted one. Like other hadrosaurs, Tsintaosaurus probably lived and traveled in herds.

Discovery and naming

In 1950, at Hsikou, near Chingkangkou, in Laiyang, Shandong, in the eastern part of China, various remains of large hadrosaurids were uncovered. In 1958 these were described by Chinese paleontologist Yang Zhongjian ("C.C. Young") as the type species Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus. The generic name is derived from the city of Qingdao, earlier often transliterated as "Tsintao". The specific name means "with a nose spine", from Latin spina, and Greek ῥίς, rhis, "nose", in reference to the distinctive crest on the snout.[1]

The holotype, IVPP AS V725, was discovered in a layer of the Jingangkou Formation, part of the Wangshi Group dating from the Campanian. It consists of a partial skeleton with skull. The paratype is specimen IVPP V818, a skull roof. In the same area some additional partial skeletons and a large number of disarticulated skeletal elements were found. Some of these were by Yang referred to Tsintaosaurus, others were named as a Tanius chingkankouensis Yang 1958; also a Tanius laiyangensis Zhen 1976 exists. The latter two species are today either considered junior synonyms or nomina dubia. Later researchers would refer a larger part of the material to Tsintaosaurus.

Description

Crest

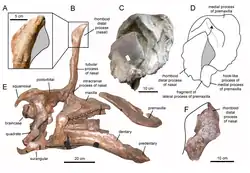

Tsintaosaurus was originally reconstructed with a unicorn-like crest on its skull. The crest, as preserved, consists of an about forty centimetres long process, protruding almost vertically from the top of the rear snout. The structure is hollow and seems to have a forked upper end. Comparable structures with related species are unknown: they possess more lobe-like crests. In 1990, David B. Weishampel and Jack Horner cast doubt on the presence of the crest, suggesting that it was actually a broken nasal bone from the top of the snout distorted upward by a crushing of the fossil. Their study further suggested that, without the distinctive crest to distinguish it, Tsintaosaurus was actually a synonym of the similar but crestless hadrosaur Tanius. However, in 1993 Éric Buffetaut e.a., after a renewed investigation of the bones themselves, concluded that the crest was neither distorted nor an artefact of restoration; besides, a second specimen with an upright crest part had since been discovered, indicating that the crest was indeed real and Tsintaosaurus is likely a distinct genus.[4]

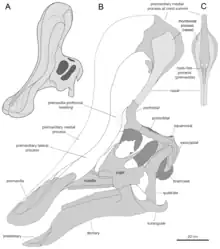

A new reconstruction in 2013, by Albert Prieto-Márquez and Jonathan Wagner and based on the identification of specimen IVPP V829, a praemaxilla, as a Tsintaosaurus element, came to the conclusion that the unicorn-like bone was just the rear part of a larger cranial crest that started from the tip of the snout. The front of the crest would have been formed by ascending processes of the praemaxillae. These had expanded rhomboid contact facets with the expanded upper parts of the crest processes of the nasal bones, forming the rear of the crest. The rear base of the crest was covered by outgrowths of the prefrontals. The fused nasal bones would have formed a hollow tubular structure. The height of the crest would have exceeded that of the rear skull, measured along the quadrates. Though largely vertical, the crest is directed slightly to the rear; the forward inclination of the holotype crest would be the result of a distortion of the fossil.[5]

The new reconstruction by Prieto-Márquez and Wagner also led to a new hypothesis about the internal air passages of the crest. Yang had assumed that the tubular hollowing in the preserved part of the holotype would have served as the main intake of air. This was rejected by Prieto-Márquez and Wagner who pointed out that the tube was closed at its lower end and that with lambeosaurines in general the air passages are located in a more forward position, the bony nostrils being completely enclosed by the praemaxillae. They assumed that Tsintaosaurus would have had a standard lambeosaurine arrangement in the snout, the air, when inhaling, entering the skull through the paired pseudonares, the "fake nostrils" of the praemaxillae behind the upper beak. From there the air would have been transported through paired passages below the median processes of the praemaxillae to the top of the crest, subsequently entering a common median chamber within the lobe. The rear of the chamber was formed by the nasal bones and probably homologous to the nasal cavity. The chamber was divided into two smaller cavities, one at the front, the other at the rear, by curved median processes of the praemaxillae, forming hooks around a passage between the cavities. From the rear cavity the air was transported to below, towards the internal skull cavity. Although it is usually assumed that a single passage served for this purpose, Prieto-Márquez and Wagner saw indications in the form of the nasal that there were paired downward passages, to the inside of the lateral processes of the praemaxillae. From this they concluded that the entire airflow was likely separated, the common medium chamber probably being divided into a left and right section by a cartilaginous septum.[5]

The conclusion that the tubular structure in the rear nasal bones was not an air passage, forced Prieto-Márquez and Wagner to find an alternative explanation of its function. They suggested that it would have served to lessen the weight of the crest, such a tube combining relative strength with a low bone mass. Tsintaosaurus would have differed in this from more derived lambeosaurines, which have a front extension of the frontal bone, in the form of a bone sheet, supporting the crest.[5]

Other distinctive traits

Apart from the crest, Prieto-Márquez and Wagner identified several other distinctive traits (autapomorphies) of Tsintaosaurus. The rim of the upper beak is rounded and thick, wider than the transverse width of the front depression around the nostrils. As far as this depression is situated on the praemaxillae, it is at each side divided lengthwise by two ridges obliquely continuing to below and sideways. Internally, the fused nasal bones form a bony block in front of the braincase. The rear of the nasal bone is clipped by front extensions of the frontal bone, the topmost of which is elevated relative to the skull roof. The ascending branches of the praemaxillae have internal processes pointing to behind, below and slightly inside, dividing a shared chamber at the midline. The prefrontal possesses a flange, continuing from the lower part of the lacrimal bone to the lower part of the ascending process of the prefrontal, and connecting to a process on the side of the praemaxilla to form an elevation on the side of the crest base. The side and the underside of the prefrontal show deep vertical grooves. The supratemporal fenestra is, transversely, wider than long.[5]

Classification

Tsintaosaurus may form a clade in Lambeosaurinae with the European genera Pararhabdodon and Koutalisaurus (probable synonym of Pararhabdodon).[6]

The position of Tsintaosaurus in the evolutionary tree according to a 2013 study by Prieto-Márquez e.a. is indicated by this cladogram:[7]

| Lambeosaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

A study of dinosaur eggs in successive layers of the Wangshi Series of Shandong province, of which the Jingangkou Formation is the most recent layer, shows that the region was one of high dinosaur diversity and that the climate had become drier from the preceding Jiangjunding Formation.[8]

See also

References

- Young, C.-C. (1958). "The dinosaurian remains of Laiyang, Shantung". Palaeontologia Sinica, New Series C. Whole Number. 42 (16): 1–138.

- Creisler, B. (2002). "Dinosauria Translation and Pronunciation Guide T". DOL Dinosaur Omnipedia. Archived from the original on 31 December 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- Gregory S. Paul (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. United States: Princeton University Press. pp. 308. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- Buffetaut, E.; Tong, H. (1993). "Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus Young and Tanius sinensis Wiman: a preliminary comparative study of two hadrosaurs (Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of China". C.R. Academy of Science Paris. 2. pp. 1255–1261.

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J. R. (2013). "The 'Unicorn' Dinosaur That Wasn't: A New Reconstruction of the Crest of Tsintaosaurus and the Early Evolution of the Lambeosaurine Crest and Rostrum". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e82268. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882268P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082268. PMC 3838384. PMID 24278478.

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J. R. (2009). "Pararhabdodon isonensis and Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus: a new clade of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids from Eurasia". Cretaceous Research. online preprint (5): 1238–1246. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.06.005. hdl:2152/41080. S2CID 85081036.

- Prieto-Marquez, A.; Vecchia, F. M. D.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, A. (2013). "Diversity, relationships, and biogeography of the Lambeosaurine dinosaurs from the European archipelago, with description of the new aralosaurin Canardia garonnensis". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69835. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869835P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069835. PMC 3724916. PMID 23922815.

- Zhao, ZiKui; Zhang, ShuKang; Wang, Qiang; Wang, XiaoLin (2013). "Dinosaur diversity during the transition between the middle and late parts of the Late Cretaceous in eastern Shandong Province, China: Evidence from dinosaur eggshells". Chinese Science Bulletin. 58 (36): 4663–4669. Bibcode:2013ChSBu..58.4663Z. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-6059-9. S2CID 131373599.