Himba people

The Himba (singular: OmuHimba, plural: OvaHimba) are an indigenous people with an estimated population of about 50,000 people[1] living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene Region (formerly Kaokoland) and on the other side of the Kunene River in southern Angola.[1] There are also a few groups left of the OvaTwa, who are also OvaHimba, but are hunter-gatherers. Culturally distinguishable from the Herero people, the OvaHimba are a semi-nomadic, pastoralist people and speak OtjiHimba, a variety of Herero, which belongs to the Bantu family within Niger–Congo.[1] The OvaHimba are semi-nomadic as they have base homesteads where crops are cultivated, but may have to move within the year depending on rainfall and where there is access to water.

OvaHimba | |

|---|---|

Himba (OmuHimba) woman | |

| Total population | |

| about 50,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| - | |

| - | |

| Languages | |

| OtjiHimba (a variety of Herero) | |

| Religion | |

| Monotheistic (Mukuru and Ancestor Reverence) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Herero people, Bantu peoples | |

The OvaHimba are considered the last (semi-) nomadic people of Namibia.

Culture

Subsistence economy

The OvaHimba are predominantly livestock farmers who breed fat-tailed sheep and goats, but count their wealth in the number of their cattle.[1] They also grow and farm rain-fed crops such as maize and millet.[1] Livestock are the major source of milk and meat for the OvaHimba. Their main diet is sour milk and maize porridge (oruhere ruomaere) and sometimes plain hard porridge only, due to milk and meat scarcity. Their diet is also supplemented by cornmeal, chicken eggs, wild herbs and honey. Only occasionally, and opportunistically, are the livestock sold for cash.[1] Non-farming businesses, wages and salaries, pensions, and other cash remittances make up a very small portion of the OvaHimba livelihood, which is gained chiefly from their work in conservancies, old-age pensions, and drought relief aid from the government of Namibia.[1]

Daily life

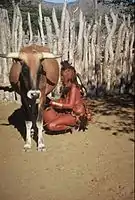

Women and girls tend to perform more labor-intensive work than men and boys do, such as carrying water to the village, earthen plastering the mopane wood homes with a traditional mixture of red clay soil and cow manure binding agent, collecting firewood, attending to the calabash vines used for producing and ensuring a secure supply of soured milk, cooking and serving meals, as well as artisans making handicrafts, clothing and jewelry.[1] The responsibility for milking the cows and goats also lies with the women and girls.[1] Women and girls take care of the children, and one woman or girl will take care of another woman's children. The men's main tasks are tending to the livestock farming, herding where the men will often be away from the family home for extended periods, animal slaughtering, construction, and holding council with village tribal chiefs.[1]

Members of a single extended family typically dwell in a homestead (onganda), a small family-village, consisting of a circular hamlet of huts and work shelters that surround an okuruwo (sacred ancestral fire) and a kraal for the sacred livestock. Both the fire and the livestock are closely tied to their veneration of the dead, the sacred fire representing ancestral protection and the sacred livestock allowing "proper relations between human and ancestor".[2]

The OvaHimba use a heterogeneous pasture system that includes both rainy-season pastures and dry-season pastures. Dry-season pastures are rested during the rainy season which results in higher biomass production in the soil compared to constantly grazing all pastures.[3]

Clothing and hair style

Both the Himba men and women are accustomed to wearing traditional clothing that befits their living environment in the Kaokoland and the hot semi-arid climate of their area. In most occurrences this consists simply of skirt-like clothing made from calfskins and sheep skin or, increasingly, from more modern textiles, and occasionally sandals for footwear. Women's sandals are made from cows' skin while men's are made from old car tires. Women who have given birth wear a small backpack of skin attached to their traditional outfit. Himba people, especially women, are famous for covering themselves with otjize paste, a cosmetic mixture of butterfat and ochre pigment. Otjize cleanses the skin over long periods due to water scarcity and protects from the hot and dry climate of the Kaokoland, as well as from insect bites. It gives Himba people's skin and hair plaits a distinctive texture, style, and orange or red tinge, and is often perfumed with the aromatic resin of the omuzumba shrub.[1] Otjize is considered foremost a highly desirable aesthetic beauty cosmetic, symbolizing earth's rich red color and blood, the essence of life, and is consistent with the OvaHimba ideal of beauty.

From pubescence, boys continue to have one braided plait, while girls will have many otjize-textured hair plaits, some arranged to veil the girl's face. In daily practice the plaits are often tied together and held parted back from the face. Women who have been married for about a year or have had a child wear an ornate headpiece called the Erembe, sculptured from sheepskin, with many streams of braided hair coloured and put in shape with otjize paste. Unmarried young men continue to wear one braided plait extending to the rear of the head, while married men wear a cap or head-wrap and un-braided hair beneath.[4][5] Widowed men will remove their cap or head-wrap and expose un-braided hair. The OvaHimba are also accustomed to use wood ash for hair cleansing due to water scarcity.

Customary practices

The OvaHimba are polygamous, with the average Himba man being husband to two wives at the same time. They also practice early arranged marriages. Young Himba girls are married to male partners chosen by their fathers. This happens from the onset of puberty,[1] which may mean that girls aged 10 or below are married off. This practice is illegal in Namibia, and even some OvaHimba contest it, but it is nevertheless widespread.[6]

Genetical testing was used in a 2020 study of a semi-nomadic group near the Angolan border. It showed that 48% of all children were conceived by a father outside of the marriage; and that more than 70% of the couples had at least one child from an extra-pair father. Furthermore, parents of both sexes could, with a reliability of 72 and 73% percent, tell which ones of their children were fathered by a man outside of the marriage.[7]

Among the Himba people, it is customary as a rite of passage to circumcise boys before puberty. Upon marriage, a Himba boy is considered a man. A Himba girl is not considered a fully-fledged woman until she bears a child.

Marriage among the OvaHimba involves transactions of cattle, which are the source of their economy. Bridewealth is involved in these transactions; this can be negotiable between the groom's family and the bride's father, depending on the relative poverty of the families involved.[8] In order for the bride's family to accept the bridewealth, the cattle must appear of high quality. It is standard practice to offer an ox, but more cattle will be offered if the groom's father is wealthy and is capable of offering more.

Societal participation

Despite the fact that a majority of OvaHimba live a distinct cultural lifestyle in their remote rural environment and homesteads, they are socially dynamic, and not all are isolated from the trends of local urban cultures. The OvaHimba coexist and interact with members of their country's other ethnic groups and the social trends of urban townsfolk. This is especially true of those in proximity to the Kunene Region capital of Opuwo, who travel frequently to shop at the local town supermarkets for the convenience of commercial consumer products, market food produce and to acquire health care.[1]

Links with Western culture

Some Himba children attend Western schools, and some young people leave the homelands to live in towns.[9]

Tribal structure

Because of the harsh desert climate in the region where they live and their seclusion from outside influences, the OvaHimba have managed to maintain and preserve much of their traditional lifestyle. Members live under a tribal structure based on bilateral descent that helps them live in one of the most extreme environments on earth.

Under bilateral descent, every tribe member belongs to two clans: one through the father (a patriclan, called oruzo) and another through the mother (a matriclan, called eanda).[11] Himba clans are led by the eldest male in the clan. Sons live with their father's clan, and when daughters marry, they go to live with the clan of their husband. However, inheritance of wealth does not follow the patriclan but is determined by the matriclan, that is, a son does not inherit his father's cattle but his maternal uncle's instead. Along with the inheritance of wealth, moral obligations are also important within the tribal structure. When a person dies, the OvaHimba evaluate the care of those who are left behind, such as orphans and widows. Access to water-points and pastures is another part of the OvaHimba inheritance structure.

Bilateral descent is found among only a few groups in West Africa, India, Australia, Melanesia and Polynesia, and anthropologists consider the system advantageous for groups that live in extreme environments because it allows individuals to rely on two sets of kin dispersed over a wide area.[12]

History

The OvaHimba history is fraught with disasters, including severe droughts and guerrilla warfare, especially during Namibia's war of independence and as a result of the civil war in neighboring Angola.

In the 1980s it appeared the OvaHimba way of life was coming to a close due to a climax in adverse climatic conditions and political conflicts.[13] A severe drought killed 90% of their livestock, and many gave up their herds and became refugees in the town of Opuwo living in slums on international humanitarian aid, or joined Koevoet paramilitary units to cope with the livestock losses and widespread famine.[13] OvaHimba living over the border in Angola were occasionally victims of kidnapping during the South African Border war, either taken as hostages or abducted to join the Angolan branch of the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN, army of SWAPO).[13]

Religion

The OvaHimba are a monotheistic people who worship the god Mukuru, as well as their clan's ancestors (ancestor reverence). Mukuru only blesses, while the ancestors can bless and curse.[14] Each family has its own sacred ancestral fire, which is kept by the fire-keeper. The fire-keeper approaches the sacred ancestral fire every seven to eight days in order to communicate with Mukuru and the ancestors on behalf of his family.[15] Often, because Mukuru is busy in a distant realm, the ancestors act as Mukuru's representatives.[15]

The OvaHimba traditionally believe in omiti, which some translate to mean witchcraft but which others call "black magic" or "bad medicine".[16] Some OvaHimba believe that death is caused by omiti, or rather, by someone using omiti for malicious purposes.[17] Additionally, some believe that evil people who use omiti have the power to place bad thoughts into another's mind[18] or cause extraordinary events to happen (such as when a common illness becomes life-threatening).[19] But users of omiti do not always attack their victim directly; sometimes they target a relative or loved one.[20] Some OvaHimba will consult a traditional African diviner-healer to reveal the reason behind an extraordinary event, or the source of the omiti.[19]

Since Namibian independence

The OvaHimba have been successful in maintaining their culture and traditional way of life.

As such, the OvaHimba have worked with international activists to block a proposed hydroelectric dam along the Kunene River that would have flooded their ancestral lands.[21] In 2011, when Namibia announced its new plan to build a dam in Orokawe, in the Baynes Mountains. The OvaHimba submitted in February 2012 their protest declaration against the hydroelectric dam to the United Nations, the African Union and to the Government of Namibia.[22]

The government of Norway and Iceland funded mobile schools for Himba children, but since Namibia took them over in 2010, they have been converted to permanent schools and are no longer mobile. The Himba leaders complain in their declaration about the culturally inappropriate school system, that they say would threaten their culture, identity and way of life as a people.

Human rights

Groups of the last remaining hunters and gatherers Ovatwa are held in secured camps in the northern part of Namibia's Kunene region, despite complaints by the traditional Himba chiefs that the Ovatwa are held there without their consent and against their wishes.[23]

In February 2012, traditional Himba chiefs[24] issued two separate declarations[25][26] to the African Union and to the OHCHR of the United Nations.The first, titled "Declaration of the most affected Ovahimba, Ovatwa, Ovatjimba and Ovazemba against the Orokawe Dam in the Baynes Mountains"[22] outlines the objections from regional Himba chiefs and communities that reside near the Kunene River. The second, titled "Declaration by the traditional Himba leaders of Kaokoland in Namibia"[25] lists violations of civil, cultural, economic, environmental, social and political rights perpetrated by the government of Namibia (GoN).

In September 2012, the United Nations special rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples visited the OvaHimba and heard their concerns that they do not have recognized traditional authorities and that they are placed under the jurisdictions of chiefs of neighboring dominant tribes, who make decisions on behalf of the minority communities. In his view, the lack of recognition of traditional chiefs, in accordance with Namibian law, relates to a lack of recognition of the minority indigenous tribes' communal lands.[27] On November 23, 2012, hundreds of OvaHimba and Zemba from Omuhonga and Epupa region protested in Okanguati against Namibia's plans to construct a dam in the Kunene River in the Baynes Mountains, against increasing mining operations on their traditional land and human rights violations against them.[28]

On March 25, 2013, over 1,000 Himba people marched in protest again, this time in Opuwo, against the ongoing human rights violations that they endure in Namibia. They expressed their frustration over the lack of recognition of their traditional chiefs as "Traditional Authorities" by the government;[29] Namibia's plans to build the Orokawe dam in the Baynes Mountains at the Kunene River without consulting with the OvaHimba, who do not consent to the construction plans; culturally inappropriate education; the illegal fencing of parts of their traditional land; and their lack of property rights to the territory that they have lived upon for centuries. They also protested against the implementation of the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002.[30]

On October 14, 2013, Himba chief Kapika, on behalf of his region Epupa and the community which was featured in German RTL reality TV show Wild Girls condemned the misuse of Himba people, individuals and villagers in the show, and demanded the halt of broadcasting any further episodes as they would mock the culture and way of being of the Himba people.[31]

In March 2014, OvaHimba from both countries, Angola and Namibia, marched again in protest against the dam's construction plans and against the government attempt to bribe their regional Himba chief. In the signed letter of the Himba community from Epupa, the region that would be directly affected by the dam, the traditional leaders explain that any consent form signed by a former chief as a result of bribery was not valid, as they remain opposed to the dam.[32]

Anthropological investigations

Color perception and vision

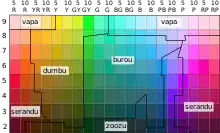

Several researchers have studied the OvaHimba perception of colours.[33] The OvaHimba use four colour names: zuzu stands for dark shades of blue, red, green and purple; vapa is white and some shades of yellow; buru is some shades of green and blue; and dambu is some other shades of green, red and brown.[34]

Like many traditional societies, the Himba have exceptionally sharp vision, believed to come from their cattle rearing and need to identify each cow's markings.[35]

Notable Ovahimba

- Vipuakuje Muharukua, member of Namibia's Parliament

See also

Himba village about 15 km north of Opuwo, Namibia

Himba village about 15 km north of Opuwo, Namibia Himba woman working, Namibia

Himba woman working, Namibia Male Himba herders

Male Himba herders Himba girl tending cattle

Himba girl tending cattle Himba woman prepares a fire. Himba huts in the background.

Himba woman prepares a fire. Himba huts in the background. As is customary in Himba culture and climate, a Himba girl of northern Namibia wears a traditional skirt made from calfskin leather, headdress and jewelry which signify her social status.

As is customary in Himba culture and climate, a Himba girl of northern Namibia wears a traditional skirt made from calfskin leather, headdress and jewelry which signify her social status. Himba woman milking a cow

Himba woman milking a cow

Literature

- Kamaku Consultancy Services cc., Commissioned by: Country Pilot Partnership (CPP) Programme Namibia (2011). Strategies That Integrate Environmental Sustainability Into National Development Planning Process to Address Livelihood Concerns of the OvaHimba Tribe in Namibia - A Summary (PDF). Windhoek, Namibia: The Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Republic of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- Bollig, Michael (2006). Risk Management in a Hazardous Environment: A Comparative Study of two Pastoral Societies. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. ISBN 9780387275819.

- Sherman, Rina. Ma vie avec les Ovahimba.

- Bardet, Solenn. Pieds nus sur la terre rouge.

- Bardet, Solenn. Rouge Himba.

References

- Kamaku Consultancy Services cc., Commissioned by: Country Pilot Partnership (CPP) Programme Namibia (2011). Strategies That Integrate Environmental Sustainability Into National Development Planning Process to Address Livelihood Concerns of the OvaHimba Tribe in Namibia - A Summary (PDF). Windhoek, Namibia: The Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Republic of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- Crandall 2000, p. 18.

- Müller, Birgit; Linstädter, Anja; Frank, Karin; Bollig, Michael; Wissel, Christian (2007). "Learning from Local Knowledge: Modeling the Pastoral-Nomadic Range Management of the Himba, Namibia". Ecological Applications. 17 (7): 1857–1875. doi:10.1890/06-1193.1. ISSN 1939-5582. PMID 17974327.

- Kcurly (4 January 2011). "Himba Hair Styling". Newly Natural. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- "Tribes of Africa. The Himba". Africa Travel. About.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- Kangootui, Nomhle (26 May 2016). "Opuwo's lonely voice against child marriages". The Namibian. p. 1.

- B. A. Scelza; S. P. Prall; N. Swinford; S. Gopalan; E. G. Atkinson; R. McElreath; J. Sheehama; B. M. Henn (2020-02-19). "High rate of extrapair paternity in a human population demonstrates diversity in human reproductive strategies". Science Advances. 6 (8): eaay6195. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.6195S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay6195. PMC 7030936. PMID 32128411.

- Crandall, D. (1998). The Role of Time in Himba Valuations of Cattle. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(1), 101-114. doi:10.2307/3034430

- "Namibia's Himba people caught between traditions and modernity". BBC News. 2017-08-30. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- Friedman, John (2011). Imagining The Post-Apartheid State: An Ethnographic Account of Namibia. Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books. p. 204. ISBN 9781782383239.

- Crandall 2000.

- Ezzell, Carol (17 June 2001). "The Himba and the Dam". Scientific American. 284 (6): 80–9. Bibcode:2001SciAm.284f..80E. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0601-80. PMID 11396346. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- Bollig, Michael (2006). Risk Management in a Hazardous Environment: A Comparative Study of two Pastoral Societies. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. pp. 167–168. ISBN 9780387275819.

- Crandall 2000, p. 188.

- Crandall 2000, p. 47.

- Crandall 2000, p. 33.

- Crandall 2000, pp. 38–39.

- Crandall 2000, p. 102.

- Crandall 2000, p. 66.

- Crandall 2000, p. 67.

- "Namibia: Dam will mean our destruction, warn Himba". IRIN. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 18 January 2008.

- "Declaration of the most affected Ovahimba, Ovatwa, Ovatjimba and Ovazemba against the Orokawe Dam in the Baynes Mountains". Earth Peoples. 7 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Cupido, Delme (28 February 2012). "Indigenous coalition opposed to new dam". OSISA. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- "Indigenous Himba Appeal to UN to Fight Namibian Dam". Galdu. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Declaration by the traditional Himba leaders of Kaokoland in Namibia". Earth Peoples. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-07-27. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Namibian Minority Groups Demand Their Rights". Newsodrome. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Statement of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, upon concluding his visit to Namibia from 20-28 September 2012". OHCHR. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- Sommer, Rebecca (23 November 2012). "Namibia: Indigenous semi-nomadic Himba and Zemba march in protest against dam, mining and human rights violations". Earth Peoples. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- "German GIZ directly engaged with dispossessing indigenous peoples of their lands and territories in Namibia". earthpeoples.org. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- Sasman, Catherine. "Himba, Zemba reiterate 'no' to Baynes dam". Allafrica. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- "Indigenous peoples Himba community condemn RTL TV series Wild Girls, asking Earth Peoples co-founder Rebecca Sommer for help to intervene on their behalf and stop it". Earth Peoples. Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2013-10-16.

- Sommer, Rebecca. "NAMIBIA Semi-nomadic HIMBA march again in protest against dam construction and government attempt to bribe Himba chief's consent". earthpeoples.org. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- Roberson, Debi; Davidoff, Jules; Davies, Ian R.L.; Shapiro, Laura R. "Colour Categories and Category Acquisition in Himba and English" (pdf). The Department of Psychology. University of Essex. Retrieved 2012-05-28.

- Reiger, Terry; Kay, Paul (28 August 2009). "Language, thought, and color: Whorf was half right" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 13 (10): 439–446. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.07.001. PMID 19716754. S2CID 2564005. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- Robson, David (26 June 2020). "The astonishing vision and focus of Namibia's nomads". Retrieved 27 June 2020.

Further reading

- Crandall, David P. (2000). The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees: A Year in the Lives of the Cattle-Herding Himba of Namibia. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. pp. 18, 33, 38–39, 47, 48, 66, 67, 102, 188. ISBN 0-8264-1270-X.

- Peter Pickford, Beverly Pickford, Margaret Jacobsohn: Himba; ed. New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd, 1990; ISBN 978-1-85368-084-7

- Klaus G. Förg, Gerhard Burkl: Himba. Namibias ockerrotes Volk; Rosenheim: Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 2004; ISBN 3-475-53572-6 (in German)

- Rina Sherman: Ma vie avec les Ovahimba; Paris: Hugo et Cie, 2009; ISBN 978-2-7556-0261-6 (in French)

External links

- Himbas, struggle for survive; a long term documentary by photojournalist and filmmaker Delmi Alvarez

- A Peace Corps volunteer works among the Himba

- HIMBA CUSTOMS from Namibia. Extract from Last Free Men by José Manuel Novoa

- HIMBA DANCE in Omuhonga, Kaokoland, Namibia, video by Rebecca Sommer

- Association Kovahimba, created by Solenn Bardet

Photographs

- The Ovahimba Years – photography by Rina Sherman

- The Himba Tribe – photography by Klaus Tiedge

- Photos of the Himba People in Okangwati Archived 2014-08-15 at the Wayback Machine – photography by Benjamin Rennicke

- Photos from Himba village near Opuwo, Namibia – photographs and information

- Africa on the Matrix: Himba People of Namibia – photographs and information

Movies

- The Himba are shooting – movie by Solenn Bardet (French and English)