Public Works of Art Project

The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was a New Deal work-relief program that employed professional artists to create sculptures, paintings, crafts and design for public buildings and parks during the Great Depression in the United States.[1][2] The program operated from December 8, 1933, to May 20, 1934,[3] administered by Edward Bruce under the United States Treasury Department, with funding from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

Negro Mother and Child (1934) by Maurice Glickman, commissioned by PWAP and installed at the Stewart Lee Udall Department of the Interior Building in 1940 | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 8, 1933 |

| Dissolved | May 20, 1934 |

| Parent agency | United States Department of the Treasury |

Although the program lasted less than one year, it had employed 3,749 artists, who produced 15,663 works of art.[4][5] In an art exhibition that featured 451 paintings commissioned by the PWAP, 30 percent of the artists featured were in their twenties, and 25 percent were first-generation immigrants.[5] The PWAP served as way to employ artists, while having competent representatives of the profession create work for display work in a public setting.[4] According to one news report at the PWAP show at MoMA, "The artists selected for the program were chosen on the basis of their artistic qualifications and their need of employment. The subject assigned to them was the American scene in all its phases."[6]

Overview and purpose

The purpose of the Public Works of Art Project was "to give work to artists by arranging to have competent representatives of the profession embellish public buildings."[7] Artworks from the project were shown or incorporated into a variety of locations, including the White House and the House of Representatives.[7] Artists were paid an average of $75.59 per artwork, and the PWAP used a total of $1,184,400 to pay artists for their work.[8] Participants were required to be professional artists, and in total, 3,749 artists were hired, and 15,663 works were produced:[8] 7,000 easel paintings; 700 mural projects; 750 sculptures; and 2500 works of graphic art were commissioned by the PWAP.[9]

The PWAP sought to produce images focused on the "American Scene", and commissioned paintings and murals that depicted "optimistic visions of America during a time of economic desperation."[10] However, many artists disliked the idea of creating art that focused only on the positive aspects of living in America, as people were still experiencing dire hardships and personal tragedies from the Great Depression.[10] This created a community of PWAP artists who aspired to create artworks depicting both the "haves" and "have nots" of America, referred to as Social Realists.

The short-lived Public Works of Art Project was a prototype for later federal art programs, including the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Subsequent visual art programs administered by the Treasury Department were the Section of Painting and Sculpture and the Treasury Relief Art Project, both of which employed artists to decorate federal buildings throughout the U.S.[2]

History

The vision and advocacy of artists George Biddle and Edward Bruce are credited for the creation and management of the New Deal art programs of the United States Department of the Treasury. On May 9, 1933, Biddle wrote a letter to newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposing that the U.S. government designate funds for murals in federal buildings "to improve the quality of American life". Roosevelt arranged for him to meet with L. W. Robert Jr., Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, who was responsible for the federal building construction program. At their June meeting, Biddle learned that funds had been approved to decorate the new Department of Justice and Post Office buildings in Washington, D.C., but that Congress was reluctant to have the appropriated funds spent on art. Biddle sent a proposal to a number of government officials, as well as Eleanor Roosevelt, who shared it with FDR. They both approved of the concept, as did Robert and architect Charles Louis Borie Jr., who designed the Justice building.[11] The proposal's greatest advocate was Ned Bruce, an artist as well as an expert on monetary policy who had joined the Treasury Department in 1932. In October 1933, Bruce had a series of gatherings at his home to discuss the possibility of government support for the visual arts. When the funding source was identified as the sticking point, Biddle and Bruce met with Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, who administered the Public Works Administration. Ickes supported the art program that was proposed, and believed it could be funded by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, led by Harry L. Hopkins. Recognizing the value of a work-relief program for workers in the visual arts, Hopkins allocated $1 million in FERA funds to the program.[11]

On December 11, 1933, the Public Works of Art Project was approved and announced. "The project is expected to encourage and inspire artists to depict a permanent record of the times," reported The Washington Star. The program operated under the general supervision of Robert, advised by the Advisory Committee to the Treasury on Fine Arts. This group was made up of Charles Moore, chair of the Fine Arts Commission; Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Rexford Tugwell; Henry Hopkins; Henry T. Hunt of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration of Public Works; Frederic A. Delano, director of the National Capital Planning Commission, who chaired the committee; and Bruce, who was secretary. Art critic and writer Forbes Watson (1879–1960) served as the project's technical director.[12]

PWAP was organized into 16 regional districts headed by the following administrators:[13]

- Region 1: Francis H. Taylor, director, Worcester Art Museum

- Region 2: Juliana R. Force, director, Whitney Museum of American Art

- Region 3: Fiske Kimball, director, Pennsylvania Museum of Art

- Region 4: Duncan Phillips, director, Phillips Memorial Gallery

- Region 5: J. J. Haverty, president, High Museum of Art

- Region 6: Ellsworth Woodward, director, Isaac Delgado Museum of Art, president of the Southern States Art League

- Region 7: Louis La Beaume, president, City Art Museum of St. Louis

- Region 8: Homer Saint-Gaudens, director, Carnegie Institute

- Region 9: William M. Milliken, director, Cleveland Museum of Art

- Region 10: Walter S. Brewster

- Region 11: George H. Williamson, Colorado chapter president, American Institute of Architects

- Region 12: John S. Ankeney, director, Dallas Art Association

- Region 13: Jesse L. Nusbaum

- Region 14: Merle Armitage, Southern California regional director

- Region 15: Walter Heil, director, California Palace of the Legion of Honor

- Region 16: Burt Brown Barker, University of Oregon

Notable works

Coit Tower murals

The first and largest of the projects sponsored by the PWAP were the murals in San Francisco's Coit Tower, begun in December 1933 and completed in June 1934. A total of 44 artists and assistants were employed, many of them faculty or former students of the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA). Among the lead artists were Maxine Albro, Victor Arnautoff, Jane Berlandina, Ray Bertrand, Roy Boynton, Ralph Chesse, Ben Cunningham, Rinaldo Cuneo, Harold Mallette Dean, Parker Hall, Edith Hamlin, George Albert Harris, William Hesthal, John Langley Howard, Lucien Labaudt, Gordon Langdon, Jose Moya del Pino, Otis Oldfield, Frederick E. Olmsted, Suzanne Scheuer, Ralph Stackpole, Edward Terada, Frede Vidar, Clifford Wight, and Bernard Zakheim.

After a majority of the murals were completed, the Big Strike of 1934 shut down the Pacific Coast. Though it has been claimed that allusions to the event were subversively included in the murals by some of the artists, in fact the murals were largely completed before the strike began and none of those that were not completed by that time show any reference to the strike.[14]

Griffith Observatory's Astronomers Monument

The Astronomers Monument, commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project in 1933, sits outside of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, California. The Astronomers Monument was designed by Archibald Garner, and created by Garner and five other artists.[15] Each artist was responsible for sculpting one of the astronomers featured in the monument, and in total the monument features six influential astronomers: Hipparchus (about 150 BC); Nicholas Copernicus (1473–1543); Galileo Galilei (1564–1642); Johannes Kepler (1571–1630); Isaac Newton (1642–1727); and William Herschel (1738–1822). One of the artists, George Stanley, was also the creator of the famous "Oscar" statuette presented at the Academy Awards.

On November 25, 1934, about six months prior to the opening of the Observatory, a celebration took place to mark the completion of the Astronomers Monument. The only "signature" on the Astronomers Monument is "PWAP 1934" referring to the program which funded the project and the year it was completed.

Muse of Music, Dance, Drama

.jpg.webp)

This Art Deco style monument serves as the gateway to the Hollywood Bowl, and is said to be the largest of hundreds of monuments in Southern California constructed during the New Deal.[16] The 200-foot long, 22-foot high sculpture is also a fountain and was constructed with concrete and covered with slabs of decorative granite.

The structure was completed in 1940 by George Stanley, also a contributor to the Griffith Observatory's Astronomers Monument and who is better known as the sculptor who molded the original Academy Awards' Oscar statue. The structure was refurbished in 2006.[17]

Selected easel paintings

Golden Gate Bridge

Golden Gate Bridge was commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project in 1934. The artist, Ray Strong, painted a depiction of the Golden Gate Bridge while it was under construction. Building the Golden Gate Bridge seemed impossible at the time it was built, due to the wind and overall complexity of the bridge design.[18] This painting was commissioned as a tribute to the engineering and design feats undertaken during the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge. This painting represents the American Idealism art style.[18]

Connecticut Barns

This 1934 painting was not recognized as being the work of Charles Sheeler until a General Services Administration art researcher found it in an Interior Department closet in 1983. It was not known that Sheeler had been employed by the Public Works of Art Project because the artist's name had been misspelled in government records. He was paid $221.85 for Connecticut Barns. Its title distinguishes it from a similar watercolor—Connecticut Barns in Landscape—measuring 4 by 5 inches, which is thought to be a study for this oil canvas.[19]

Additional works

Dewey Albinson, Northern Minnesota (Minnesota)

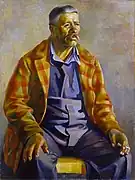

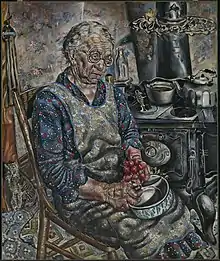

Dewey Albinson, Northern Minnesota (Minnesota) Ivan Albright, The Farmer’s Kitchen (Illinois)

Ivan Albright, The Farmer’s Kitchen (Illinois) Bernard Badura, Quarry at New Hope (Pennsylvania)

Bernard Badura, Quarry at New Hope (Pennsylvania) Laverne Nelson Black, Jicarilla Apache Fiesta (New Mexico)

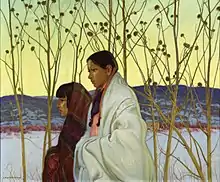

Laverne Nelson Black, Jicarilla Apache Fiesta (New Mexico) Norman S. Chamberlain, Corn Dance, Taos Pueblo (California)

Norman S. Chamberlain, Corn Dance, Taos Pueblo (California) George A. Danchuk, Aircraft No. 5 (Ohio)

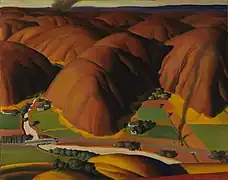

George A. Danchuk, Aircraft No. 5 (Ohio) Ross Dickinson, Valley Farms (California)

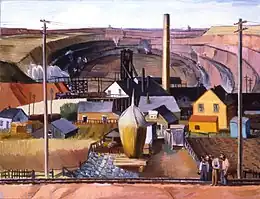

Ross Dickinson, Valley Farms (California) Arthur Durston, Industry (California)

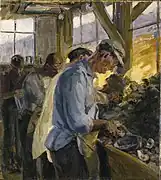

Arthur Durston, Industry (California) Claire Falkenstein, Inside a Lumber Mill (California)

Claire Falkenstein, Inside a Lumber Mill (California) Gerald Sargent Foster, Racing (New Jersey)

Gerald Sargent Foster, Racing (New Jersey) Harry Louis Freund, Clinton, Mo. (Missouri)

Harry Louis Freund, Clinton, Mo. (Missouri) Lily Furedi, Subway (New York)

Lily Furedi, Subway (New York) Lloyd Goff, Suburban Apartments (New York)

Lloyd Goff, Suburban Apartments (New York) Z. Vanessa Helder, Alki Point Lighthouse (Washington)

Z. Vanessa Helder, Alki Point Lighthouse (Washington) Ernest Martin Hemmings, Homeward Bound (New Mexico)

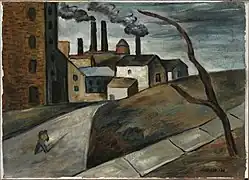

Ernest Martin Hemmings, Homeward Bound (New Mexico) Louis Hirshman, The Factory (Pennsylvania)

Louis Hirshman, The Factory (Pennsylvania) Catherine M. Howell, Oyster Shuckers (Louisiana)

Catherine M. Howell, Oyster Shuckers (Louisiana) Rowland Lyon, Georgetown Waterfront (Washington, D.C.)

Rowland Lyon, Georgetown Waterfront (Washington, D.C.) Ila Mae McAfee, Mountain Lions (New Mexico)

Ila Mae McAfee, Mountain Lions (New Mexico) Frank Mechau, Horses at Night (Colorado)

Frank Mechau, Horses at Night (Colorado)

Ernest Ralph Norling, The Timber Bucker (Washington)

Ernest Ralph Norling, The Timber Bucker (Washington) John T. Robertson, Old Man River (Iowa)

John T. Robertson, Old Man River (Iowa)_SAAM-1964.1.23_1.jpg.webp) William S. Schwartz, Americana (No. 2) (Illinois)

William S. Schwartz, Americana (No. 2) (Illinois) Gale Stockwell, Parkville, Main Street (Missouri)

Gale Stockwell, Parkville, Main Street (Missouri) Elizabeth F. Summers, Untitled (Missouri)

Elizabeth F. Summers, Untitled (Missouri) Charles W. Ward, Industry (New Jersey)

Charles W. Ward, Industry (New Jersey) Santos Zingale, Lynch Law (Wisconsin)

Santos Zingale, Lynch Law (Wisconsin) Anonymous, Underpass—Binghamton, New York (New York)

Anonymous, Underpass—Binghamton, New York (New York)

Exhibitions

Los Angeles

An exhibition of Region 14 paintings and sculptures by 100 artists was presented March 11–25, 1934, at the Los Angeles Museum. Los Angeles Times critic Arthur Millier called the show a "Southern California Renaissance".[20] Some 300 pieces were shown; Millier mentioned the following as emblematic of the "young, vigorous, colorful, varied" product of the PWAP artists:

- CCC Workers bas relief, Donal Hord (later installed South Pasadena Junior High)

- The Law, Archibald Garner (later installed Spring Street Courthouse)

- Indian Girl, Eugenia Everett

- "Three lovely figures," Ada May Sharpless

- Decorative panels by Arthur Ames, James Redmond, William P. Everett, Conrad Buff

- Paintings by Kim Clarke of ships and railroads

- Watercolors by James Couper Wright, Joseph DeMers, Milford Zornes, and Everett L. Bryant

A report in the Los Angeles Post-Record said the show was drawing "huge crowds."[21]

Baltimore

The Baltimore Museum of Art showed works by 30 PWAP artists from April 1–21, 1934, including a painting of the waterfront by Charles H. Walther.[22] A second show was put on at the Maryland Institute in December 1934.[23]

Cincinnati

The Cincinnati Museum of Art hosted a PWAP show April 22 to 29, 1934, including drawings of local subjects by local artist Glen Tracy.[24]

Washington, D.C.

On Tuesday, April 24, 1934, FDR and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt attended the opening of National Exhibition of Art by the Public Works of Art Project,[25] a Corcoran Gallery of Art show of 500 pieces created by PWAP artists.[26] New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell listed the following "smaller paintings" as those he wanted on the record as "especially successful":

- Tenement Flats by Millard Sheets

- San Pedro Harbor by Paul Starrett

- Vendue by Robert Tabor

- Old Baltimore Waterfront by Herman Maril

- Barge Dock by Erle Loran

- Old Pennsylvania Farm by A.E. Cederquist

- New England House by H.A. Coon

- Spring Plowing by Helen Dickson

- Waterfront Scene by Pino Lanni

- The Young Artist by Gertrude A. Lambert

- Winter Afternoon, Central Park by Agnes Tait

- The Snow Shovelers by Jacob Getlar Smith

- Paper Workers by Douglass Crockwell

- Interior by Josephine Wupper

- The Covered Bridge by Ivan Hoon

The New York Times featured photographs of three other paintings: Central Park by Carl Gustaf Nelson, Family Quilting by Dorothea Tomlinson, and The Squall by Gerald Foster.[26]

About half of the pieces of art from the Corcoran show became part of a traveling show. The first stop was the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, where about 150 pieces where exhibited from September 19 to October 7.[27] MoMA selected Employment of Negroes in Agriculture for inclusion in their show; "Earle Richardson's lush portrayal of four black cotton workers was the sole painting by a black artist" included in the show, and the first-ever exhibition of black art at MoMA.[28] The Everhart Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania hosted a further scaled-down version of this show from October 24 to 30, 1934, with an exhibit of 50 oil paintings and watercolors.[29][30]

Birmingham

In June 1934, the Birmingham Public Library exhibited an oil painting of the Tannehill Furnace by Carrie Hill, a portrait of John Herbert Phillips by Mrs. Effie Gibson, and had received but had yet to display five prints by "Eastern" artists.[31]

Indianapolis

There was a PWAP show at the Herron Institute in Indiana in June 1934.[32]

Brooklyn

The Brooklyn Museum hosted a show in October 1934 of "31 contemporary artists, featuring accessions acquired through the Public Works of Art Project."[33]

Wilmington, Delaware

The Fine Arts Society of the Wilmington City Library put on a show of local PWAP art from October 15 to 27, 1934.[34]

See also

- Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–1943)

- Treasury Relief Art Project (1935–1938)

- Federal Art Project (1935–1943)

References

- Public Works of Art Project. Report of the Assistant Director of the Treasury to Federal Emergency Relief Administrator, December 8, 1933 – June 30, 1934. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1934. p. 1.

- "Public Works of Art Project selected administrative and business records, 1933–1936". Archives of American Art. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- Public Works of Art Project. Report of the Assistant Director of the Treasury to Federal Emergency Relief Administrator, December 8, 1933 – June 30, 1934. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1934. p. 13.

- provided by John R. Graham, Curator of Exhibits, Western Illinois University Art Gallery, 1 University Circle, Macomb, Illinois 61455

- Brown, Elizabeth. "1934: A New Deal for Artists". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- "PWA Art Work Shown at New York Museum, The Baltimore Sun 30 Sep 1934, page 65". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- Brown, Elizabeth. ""1934: A New Deal for Artists"". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- Adler, Jerry (June 2009). "An Exhibition of Depression-Era Paintings by Federally-Funded Artists Provides a Hopeful View of Life during Economic Travails". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- "Public Works of Art Project". Britannica. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- Fogel, Jared (Fall 2001). "The Canvas Mirror: Painting as Politics in the New Deal". OAH Magazine of History. 16 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1093/maghis/16.1.17. JSTOR 25163482.

- "WPA Art Collection". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- "Public Art Works Plans to Beautify Federal Buildings; 2,500 Artists to Be Employed Throughout the United States". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. December 11, 1933. p. 1.

- Public Works of Art Project. Report of the Assistant Director of the Treasury to Federal Emergency Relief Administrator, December 8, 1933 – June 30, 1934. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1934. pp. 3–4.

- Masha Zakheim, Coit Tower, San Francisco: Its History and Art, 2nd edn., 2009

- "Astronomers Monument & Sundial". Griffith Observatory. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- "Muse of Music, Dance, Drama | LA County Arts Commission". www.lacountyarts.org. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Pool, Bob (2006-06-20). "Getting a Splash From the Past". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- "Golden Gate Bridge". Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- Conroy, Sarah Booth (August 10, 1983). "GSA Finds Lost Sheeler Canvas". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Millier, Arthur (1934-03-11). "Federal Art Exhibition on Today as Museum Reopens: Public Works Show of Paintings Sculpture Called Southland Renaissance; Two Weeks Display". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. ProQuest 163195140.

- "Los Angeles Evening Post-Record 12 Mar 1934, page 5". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "Three Important Exhibitions to Open at the Museum, The Baltimore Sun 01 Apr 1934, page 56". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "The Baltimore Sun 23 Dec 1934, page 52". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "The Cincinnati Enquirer 22 Apr 1934, page Page 51". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "Public Works of Art Project articles and exhibition catalog, 1933-1934 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- Jewell, Edward Alden (1934-04-29). "THE REALM OF ART: THE PUBLIC WORKS OF ART PROJECT; IN A NATIONAL MIRROR". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- "Oakland Tribune 29 Apr 1934, page Page 34". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "The Artist Wasn't Present: On MoMA's Fumbled First Showing of Black American Art". ARTnews.com. 2019-07-17. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "The Tribune 04 Oct 1934, page Page 10". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "Public Works Art Exhibit at Museum, The Tribune, 24 Oct 1934, page 6". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- "Music and Art Notes". The Birmingham News. 1934-06-24. p. 27. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "The Indianapolis Star 24 Jun 1934, page Page 52". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 21 Oct 1934, page 30". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- "The News Journal 10 Oct 1934, page 13". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

Further reading

- Contreras, Belisario R. (1983). Tradition and Innovation in New Deal Art. London and Toronto: Associated University Presses.

- Fogel, Jared. (2001). "The Canvas Mirror: Painting as Politics in the New Deal." OAH Magazine of History. 16: 9.

- Pohl, Frances K. (2008). Framing America. A Social History of American Art. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28715-6.

- Contreras, Belisario R. (1983). Tradition and Innovation in New Deal Art. London and Toronto: Associated University Presses.

- O'Connor, Francis V., ed. (1973). Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project. Boston: New York Graphic Society. ISBN 9780821204399.

- "1934: A New Deal for Artists" is an exhibition featuring artworks from the Public Works of Art Project at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. This site contains a slide show, public programs, and recent news stories

- Public Works of Art Project, video

External links

- Smithsonian Museum of American Art: PWAP paintings Flickr album

- Public Works of Art Project. Report of the Assistant Director of the Treasury to Federal Emergency Relief Administrator, December 8, 1933 – June 30, 1934 (HathiTrust)

- Living New Deal Project, a digital database of the lasting effects of the New Deal, Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley

- New Deal Art Registry

- 1934: A New Deal for Artists, a link to Anne Prentice Wagner's article, "1934: A New Deal for Artists" in the Spring 2009 issue of ' Antiques and Fine Art magazine.

- Additional photographs of the Coit Tower murals by Maxine Albro, Victor Arnautoff, et al.