Paavo Nurmi

Paavo Johannes Nurmi (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈpɑːʋo ˈnurmi] ⓘ; 13 June 1897 – 2 October 1973) was a Finnish middle-distance and long-distance runner. He was called the "Flying Finn" or the "Phantom Finn", as he dominated distance running in the 1920s. Nurmi set 22 official world records at distances between 1500 metres and 20 kilometres, and won nine gold and three silver medals in his 12 events in the Summer Olympic Games. At his peak, Nurmi was undefeated for 121 races at distances from 800 m upwards. Throughout his 14-year career, he remained unbeaten in cross country events and the 10,000 metres.

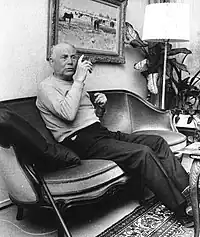

.jpg.webp) Nurmi at the 1920 Summer Olympics | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Paavo Johannes Nurmi[1] |

| Born | 13 June 1897[2] Turku, Grand Duchy of Finland[2] |

| Died | 2 October 1973 (aged 76)[2] Helsinki, Finland[2] |

| Height | 174 cm (5 ft 9 in)[1] |

| Weight | 65 kg (143 lb)[1] |

| Sport | |

| Country | Finland |

| Sport | Athletics |

Medal record | |

Born into a working-class family, Nurmi left school at the age of 12 to provide for his family. In 1912, he was inspired by the Olympic feats of Hannes Kolehmainen and began developing a strict training program. Nurmi started to flourish during his military service, setting Finnish records in athletics en route to his international debut at the 1920 Summer Olympics. After winning a silver medal in the 5000 m, he won gold in the 10,000 m and the cross country events. In 1923, Nurmi became the first runner to hold simultaneous world records in the mile, the 5000 m and the 10,000 m races, a feat which has never been repeated. He set new world records for the 1500 m and the 5000 m with just an hour between the races, and took gold medals in both distances in less than two hours at the 1924 Summer Olympics. Seemingly unaffected by the Paris heat wave, Nurmi won all his races and returned home with five gold medals,[3] although he was frustrated that Finnish officials had refused to enter him for the 10,000 m.

Struggling with injuries and motivation issues after his exhaustive U.S. tour in 1925, Nurmi found his long-time rivals Ville Ritola and Edvin Wide ever more serious challengers. At the 1928 Summer Olympics, Nurmi recaptured the 10,000 m title but was beaten for the gold in the 5000 m and the 3000 m steeplechase. He then turned his attention to longer distances, breaking the world records for events such as the one hour run and the 25-mile marathon. Nurmi intended to end his career with a marathon gold medal, as his idol Kolehmainen had done. In a controversial case that strained Finland–Sweden relations and sparked an inter-IAAF battle, Nurmi was suspended before the 1932 Games by an IAAF council that questioned his amateur status; two days before the opening ceremonies, the council rejected his entries. Although he was never declared a professional, Nurmi's suspension became definite in 1934 and he retired from running.

Nurmi later coached Finnish runners, raised funds for Finland during the Winter War, and worked as a haberdasher, building contractor, and stock trader, becoming one of the richest people in Finland. In 1952, he was the lighter of the Olympic Flame at the Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Nurmi's running speed and elusive personality spawned nicknames such as the "Phantom Finn", while his achievements, training methods and running style influenced future generations of middle- and long-distance runners. Nurmi, who rarely ran without a stopwatch in his hand, has been credited for introducing the "even pace" strategy and analytic approach to running, and for making running a major international sport.

Early life

his family in 1924

Nurmi was born in Turku, Finland, to carpenter Johan Fredrik Nurmi and his wife Matilda Wilhelmiina Laine.[4] Nurmi's siblings, Siiri, Saara, Martti and Lahja, were born in 1898, 1902, 1905 and 1908, respectively.[5] In 1903, the Nurmi family moved from Raunistula into a 40-square-meter apartment in central Turku, where Paavo Nurmi would live until 1932.[5] The young Nurmi and his friends were inspired by the English long-distance runner Alfred Shrubb.[4] They regularly ran or walked six kilometres (four miles) to swim in Ruissalo, and back, sometimes twice a day.[6] By the age of eleven, Nurmi ran the 1500 metres in 5:02.[4] Nurmi's father Johan died in 1910 and his sister Lahja a year later.[5] The family struggled financially, renting out their kitchen to another family and living in a single room.[4] Nurmi, a talented student, left school to work as an errand boy for a bakery.[5] Although he stopped running actively,[4] he got plenty of exercise pushing heavy carts up the steep slopes in Turku.[7] He later credited these climbs for strengthening his back and leg muscles.[7]

At 15, Nurmi rekindled his interest in athletics after being inspired by the performances of Hannes Kolehmainen, who was said to "have run Finland onto the map of the world" at the 1912 Summer Olympics.[8] He bought his first pair of sneakers a few days later.[6] Nurmi trained primarily by doing cross country running in the summers and cross country skiing in the winters.[4] In 1914, Nurmi joined the sports club Turun Urheiluliitto and won his first race on the 3000 metres.[9] Two years later, he revised his training program to include walking, sprints and calisthenics.[4] He continued to provide for his family through his new job at the Ab. H. Ahlberg & Co workshop in Turku, where he worked until he started his military service at a machine gun company in the Pori Brigade in April 1919.[4] During the Finnish Civil War in 1918, Nurmi remained politically passive and concentrated on his work and his Olympic ambitions.[4] After the war, he decided not to join the newly founded Finnish Workers' Sports Federation, but wrote articles for the federation's chief organ and criticized the discrimination against many of his fellow workers and athletes.[4]

In the army, Nurmi quickly impressed in the athletic competitions: While others marched, Nurmi ran the whole distances with a rifle on his shoulder and a backpack full of sand.[9] Nurmi's stubbornness caused him difficulties with his non-commissioned officers, but he was favoured by the superior officers,[9] despite his refusal to take the military oath even at the threat of a court-martial.[10] As the unit commander Hugo Österman was a known sports aficionado, Nurmi and few other athletes were given free time to practice.[4] Nurmi improvised new training methods in the army barracks; he ran behind trains, holding on to the rear bumper, to stretch his stride, and used heavy iron-clad army boots to strengthen his legs.[4] Nurmi soon began setting personal bests and got close for the Olympic selection.[9] In March 1920, he was promoted to corporal (alikersantti).[4] On 29 May 1920, he set his first national record on the 3000 m and went on to win the 1500 m and the 5000 m at the Olympic trials in July.[8][11]

Olympic career

1920–1924 Olympics

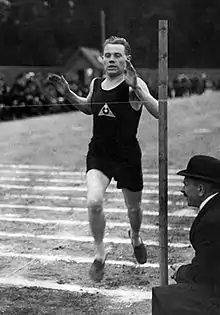

.jpg.webp)

Nurmi made his international debut in August at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium.[9] He took his first medal by finishing second to Frenchman Joseph Guillemot in the 5000 m. This would remain the only time that Nurmi lost to a non-Finnish runner in the Olympics.[8] He went on to win gold medals in his other three events: the 10,000 m, sprinting past Guillemot on the final curve and improving his personal best by over a minute,[12] the cross country race, beating Sweden's Eric Backman, and the cross country team event where he helped Heikki Liimatainen and Teodor Koskenniemi defeat the British and Swedish teams. Nurmi's success brought electric lighting and running water for his family in Turku.[5] Nurmi, however, was given a scholarship to study at the Teollisuuskoulu industrial school in Helsinki.[9]

Buoyed by his defeat to Guillemot, Nurmi's races became a series of experiments which he analyzed meticulously.[13] Previously known for his blistering pace on the first few laps, Nurmi started to carry a stopwatch and spread his efforts more uniformly over the distance.[14] He aimed to perfect his technique and tactics to a point where the performances of his rivals would be rendered meaningless.[13] Nurmi set his first world record on the 10,000 m in Stockholm in 1921.[15] In 1922, he broke the world records for the 2000 m, the 3000 m and the 5000 m.[14] A year later, Nurmi added the records for the 1500 m and the mile.[14] His feat of holding the world records for the mile, the 5000 m and the 10,000 m at the same time has not been matched by any other athlete before or since.[8] Nurmi also tested his speed in the 800 m, winning the 1923 Finnish Championships with a new national record.[16] After excelling in mathematics,[17] Nurmi graduated as an engineer in 1923 and returned home to prepare for the upcoming Olympic Games.[5][9]

Nurmi's trip to the 1924 Summer Olympics was endangered by a knee injury in the spring of 1924, but he recovered and resumed training twice a day.[16] On 19 June, Nurmi tried out the 1924 Olympic schedule at the Eläintarha Stadium in Helsinki by running the 1500 m and the 5000 m inside an hour, setting new world records for both distances.[18] In the 1500 m final at the Olympics in Paris, Nurmi ran the first 800 m almost three seconds faster.[18] His only challenger, Ray Watson of the United States, gave up before the last lap and Nurmi was able to slow down and coast to victory ahead of Willy Schärer, H. B. Stallard and Douglas Lowe,[18] still breaking the Olympic record by three seconds.[19] The 5000 m final started in less than two hours, and Nurmi faced a tough challenge from countryman Ville Ritola, who had already won the 3000 m steeplechase and the 10,000 m.[18] Ritola and Edvin Wide figured that Nurmi must be tired and tried to burn him off by running at world-record pace.[20][21] Realizing that he was now racing the two men and not the clock, Nurmi tossed his stopwatch onto the grass.[20] The Finns later passed the Swede as his pace faded and continued their duel.[18] On the home straight, Ritola sprinted from the outside but Nurmi increased his pace to keep his rival a metre behind.[18]

In the cross country events, the heat of 45 °C (113 °F),[22] caused all but 15 of the 38 competitors to abandon the race.[18] Eight finishers were taken away on stretchers.[18] One athlete began to run in tiny circles after reaching the stadium, until setting off into the stands and knocking himself unconscious.[23] Early leader Wide was among those who blacked out along the course, and was incorrectly reported to have died at the hospital.[24][25] Nurmi exhibited only slight signs of exhaustion after beating Ritola to the win by nearly a minute and a half.[18] As Finland looked to have lost the team medal, the disoriented Liimatainen staggered into the stadium, but was barely moving forward.[26] An athlete ahead of him fainted 50 metres from the finish, and Liimatainen stopped and tried to find his way off the track, thinking he had reached the finish line.[26] After having ignored shouts and kept the spectators in suspense for a while, he turned into the right direction, realised his situation and reached the finish in 12th place and secured team gold.[18][26] Those present at the stadium were shocked by what they had witnessed, and Olympic officials decided to ban cross country running from future Games.[27]

In the 3000 m team race on the next day, Nurmi and Ritola again finished first and second, and Elias Katz secured the gold medal for the Finnish team by finishing fifth.[18] Nurmi had won five gold medals in five events, but he left the Games embittered as the Finnish officials had allocated races between their star runners and prevented him from defending his title in the 10,000 m, the distance that was dearest to him.[18][28] After returning to Finland, Nurmi set a 10,000 m world record that would last for almost 13 years.[28] He now held the 1500 m, the mile, the 3000 m, the 5000 m and the 10,000 m world records simultaneously.[29]

U.S. tour and 1928 Olympics

In early 1925, Nurmi embarked on a widely publicised tour of the United States. He competed in 55 events (45 indoors) during a five-month period, starting at a sold-out Madison Square Garden on 6 January.[30] His debut was a copy of his feats in Helsinki and Paris.[30] Nurmi defeated Joie Ray and Lloyd Hahn to win the mile and Ritola to win the 5000 m, again setting new world records for both distances.[30] Nurmi broke ten more indoor world records in regular events and set several new best times for rarer distances.[30] He won 51 of the events, abandoned one race and lost two handicap races along with his final event; a half-mile race at the Yankee Stadium, where he finished second to American track star Alan Helffrich.[30][31] Helffrich's victory ended Nurmi's 121-race, four-year win streak in individual scratch races at distances from 800 m upwards.[32] Although he hated losing more than anything,[33] Nurmi was the first to congratulate Helffrich.[31] The tour made Nurmi extremely popular in the United States, and the Finn agreed to meet President Calvin Coolidge at the White House.[34] Nurmi left America fearing that he had competed too often and burned himself out.[35]

Nurmi struggled to maintain motivation for running, heightened by his rheumatism and Achilles tendon problems.[9] He quit his job as a machinery draughtsman in 1926 and began studying business intensively.[9] As Nurmi started a new career as a share dealer, his financial advisors included Risto Ryti, director of the Bank of Finland.[9] In 1926, Nurmi broke Wide's world record for the 3000 m in Berlin and then improved the record in Stockholm,[29] despite Nils Eklöf repeatedly trying to slow his pace down in an effort to aid Wide.[36] Nurmi was furious at the Swedes and vowed never to race Eklöf again.[37] In October 1926, he lost a 1500 m race along with his world record to Germany's Otto Peltzer.[38] This marked the first time in over five years and 133 races that Nurmi had been defeated at a distance over 1000 m.[32] In 1927, Finnish officials barred him from international competition for refusing to run against Eklöf at the Finland-Sweden international, cancelling the Peltzer rematch scheduled for Vienna.[39] Nurmi ended his season and threatened, until late November, to withdraw from the 1928 Summer Olympics.[40] At the 1928 Olympic trials, Nurmi was left third in the 1500 m by eventual gold and bronze medalists Harri Larva and Eino Purje, and he decided to concentrate on the longer distances.[41] He added steeplechase to his program, although he had only tried the event twice before,[41] the latest being a two-mile steeplechase victory at the 1922 British Championships.[42]

At the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, Nurmi competed in three events. He won the 10,000 m by staying right behind Ritola until sprinting past him on the home straight.[43] Before the 5000 m final, Nurmi injured himself in his qualifying heat for the 3000 m steeplechase.[43] He fell on his back at the water jump, spraining his hip and foot.[43] Lucien Duquesne stopped to help him up, and Nurmi thanked the Frenchman by pacing him past the field and offered him the heat win, which Duquesne gracefully refused.[43] In the 5000 m, Nurmi tried to repeat his move on Ritola but had to watch his teammate pull away instead.[43] Nurmi, looking more exhausted than ever before, only barely managed to keep Wide behind and take silver.[43] Nurmi had little time to rest or nurse his injuries as the 3000 m steeplechase started the next day.[43] Struggling with the hurdles, Nurmi let Finland's steeplechase specialist Toivo Loukola escape into the distance.[43] On the final lap, he sprinted clear of the others and finished nine seconds behind the world-record setting Loukola; Nurmi's time also bettered the previous record.[43] Although Ritola did not finish, Ove Andersen completed a Finnish sweep of the medals.[43]

Move to longer distances

Nurmi stated to a Swedish newspaper that "this is absolutely my last season on the track. I am beginning to get old. I have raced for fifteen years and have had enough of it."[8] However, Nurmi continued running, turning his attention to longer distances. In October, he broke the world records for the 15 km, the 10 miles and the one hour run in Berlin.[15] Nurmi's one-hour record stood for 17 years, until Viljo Heino ran 129 metres further in 1945.[44] In January 1929, Nurmi started his second U.S. tour from Brooklyn.[45] He suffered his first-ever defeat in the mile to Ray Conger at the indoor Wanamaker Mile.[46][47] Nurmi was seven seconds slower than in his world record run in 1925,[46] and it was immediately speculated if the mile had become too short a distance for him.[48] In 1930, he set a new world record for the 20 km.[15] In July 1931, Nurmi showed he still had pace for the shorter distances by beating Lauri Lehtinen, Lauri Virtanen and Volmari Iso-Hollo, and breaking the world record on the now-rare two miles.[49][50] He was the first runner to complete the distance in less than nine minutes.[49] Nurmi planned to compete only in the 10,000 m and the marathon in the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, stating that he "won't enter the 5000 metres for Finland has at least three excellent men for that event."[51]

In April 1932, the executive council of the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) suspended Nurmi from international athletics events pending an investigation into his amateur status by the Finnish Athletics Federation.[52] The Finnish authorities criticized the IAAF for acting without a hearing,[52] but agreed to launch an investigation. It was customary of the IAAF to accept the final decision of its national branch,[53] and the Associated Press wrote that "there is little doubt that if the Finnish federation clears Nurmi the international body will accept its decision without question."[52] A week later, the Finnish Athletics Federation ruled in favor of Nurmi, finding no evidence for the allegations of professionalism.[53] Nurmi was hopeful that his suspension would be lifted in time for the Games.[54]

On 26 June 1932 Nurmi started his first marathon at the Olympic trials. Not drinking a drop of liquid, he ran the old-style 'short marathon' of 40.2 km (25.0 mi) in 2:22:03.8 – on the pace to finish in about 2:29:00,[55] just under Albert Michelsen's marathon world record of 2:29:01.8. At the time, he led Armas Toivonen, the eventual Olympic bronze medalist, by six minutes.[56] Nurmi's time was the new unofficial world record for the short marathon.[57] Confident that he had done enough, Nurmi stopped and retired from the race owing to problems with his Achilles tendon.[55] The Finnish Olympic Committee entered Nurmi for both the 10,000 m and the marathon.[58] The Guardian reported that "some of his trial times were almost unbelievable,"[23] and Nurmi went on to train at the Olympic Village in Los Angeles despite his injury.[8] Nurmi had set his heart on ending his career with a marathon gold medal, as Kolehmainen had done shortly after the First World War.[59]

1932 Olympics and later career

Less than three days before the 10,000 m, a special commission of the IAAF, consisting of the same seven members that had suspended Nurmi, rejected the Finn's entries and barred him from competing in Los Angeles.[60] Sigfrid Edström, the Swedish chairman of the Council of the International Association of Athletics Federations (s.o. the board of directors), pushed independently and without receiving the support of the rules of the International Association of Athletics Federations for a decision to ban Nurmi from participating in the Los Angeles Olympics at the IAAF board meeting without consulting the Finnish Sports Federation (SUL) and Nurmi on 3.4.[61] and 7/30/1932.[62] [The rules for disqualification of an athlete were made only after the Olympics at the Congress (General Assembly) of the International Sports Federation (IAAF), where Edström and Bo Ekelund, secretary of the council, represented Sweden. The report for Nurmi's ban came from Avery Brundage, president of the American Sports Federation.][63][64] Edström stated that the full congress of the IAAF, which was scheduled to start the next day, could not reinstate Nurmi for the Olympics but merely review the phases and political angles related to the case.[60] The AP called this "one of the slickest political maneuvers in international athletic history", and wrote that the Games would now be "like Hamlet without the celebrated Dane in the cast."[65] Thousands protested against the action in Helsinki.[66] Details of the case were not released to the press, but the evidence against Nurmi was believed be the sworn statements from German race promoters that Nurmi had received $250–500 per race when running in Germany in autumn 1931.[65] The statements were produced by Karl Ritter von Halt, after Edström had sent him increasingly threatening letters warning that if evidence against Nurmi were not provided he would be "unfortunately obliged to take stringent action against the German Athletics Association."[67] The IOC did not follow their own rules for disqualification for not being a non-amateur Olympic participant. The rulebook for the 1912 Olympics stated that protests had to be made "within 30 days from the closing ceremonies of the games."[68]

On the eve of the marathon, all the entrants of the race except for the Finns, whose positions were known, filed a petition asking Nurmi's entry to be accepted.[69] Edström's right-hand man Bo Ekelund, secretary general of the IAAF and head of the Swedish Athletics Federation, approached the Finnish officials and stated that he might be able to arrange for Nurmi to participate in the marathon outside the competition.[69] However, Finland maintained that as long as the athlete is not declared a professional, he must have the right to participate in the race officially.[69] Although he had been diagnosed with a pulled Achilles tendon two weeks earlier,[70] Nurmi stated he would have won the event by five minutes.[8] The congress concluded without Nurmi being declared a professional, but the council's authority to disbar an athlete was upheld on a 13–12 vote.[71] However, due to the close vote, the matter was postponed until the 1934 meet in Stockholm.[71] Finns charged that the Swedish officials had used devious tricks in their campaign against Nurmi's amateur status,[72] and ceased all athletic relations with Sweden.[73] A year earlier, controversies on the track and in the press had led Finland to withdraw from the Finland-Sweden athletics international.[74] After Nurmi's suspension, Finland did not agree to return to the event until 1939.[72]

Nurmi refused to turn professional,[75] and continued running as an amateur in Finland.[8] In 1933, he ran his first 1500 m in three years and won the national title with his best time since 1926.[76][77] At the IAAF meet in August 1934, Finland launched two proposals that lost.[78] The council then brought forward its resolution empowering it to suspend athletes that it finds in violation of the IAAF amateur code.[78] With a 12–5 vote, with many not voting, Nurmi's suspension from international amateur athletics became definite.[78] Less than three weeks later, Nurmi retired from running with a 10,000 m victory in Viipuri on 16 September 1934.[8] Nurmi remained undefeated in the distance throughout his 14-year top-level career.[79] In cross country running, his win streak lasted 19 years.[80]

Later life

While active as a runner, Nurmi was known to be secretive about his training methods.[81] Always running alone, he upped his pace and quickly exhausted anyone who was bold enough to join him.[81] Even his club mate Harri Larva had learned little from him.[81] After ending his career, Nurmi became a coach for the Finnish Athletics Federation and trained runners for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.[16] In 1935, Nurmi along with the entire board of directors quit the federation after a heated 40–38 vote to resume athletic relations with Sweden.[82] However, Nurmi returned to coaching three months later and the Finnish distance runners went on to take three gold medals, three silvers and a bronze at the Games.[16][83] In 1936, Nurmi also opened a men's clothing store (haberdashery) in Helsinki.[84] It became a popular tourist attraction,[85] and Emil Zátopek was among those who visited the store trying to meet Nurmi.[86] The Finn spent his time in the back room, running another new business venture; construction.[84] As a contractor, Nurmi built forty apartment buildings in Helsinki with about a hundred flats in each.[87] Within five years, he was rated a millionaire.[85] His fiercest rival Ritola ended up living in one of Nurmi's flats, at half price.[59] Nurmi also made money on the stock market, eventually becoming one of Finland's richest people.[88]

In February 1940, during the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union, Nurmi returned to the United States with his protégé Taisto Mäki, who had become the first man to run the 10,000 m under 30 minutes, to raise funds and rally support to the Finnish cause.[8] The relief drive, directed by former president Herbert Hoover, included a coast-to-coast tour by Nurmi and Mäki.[89] Hoover welcomed the two as "ambassadors of the greatest sporting nation in the world."[90] While in San Francisco, Nurmi received news that one of his apprentices, 1936 Olympic champion Gunnar Höckert, had been killed in action.[91] Nurmi left for Finland in late April,[92] and later served in the Continuation War in a delivery company and as a trainer in the military staff.[93] Before he was discharged in January 1942, Nurmi was promoted first to a staff sergeant (ylikersantti) and later to a sergeant first class (vääpeli).[93]

In 1952, Nurmi was persuaded by Urho Kekkonen, Prime Minister of Finland and former chairman of the Finnish Athletics Federation, to carry the Olympic torch into the Olympic Stadium at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki.[88] His appearance astonished the spectators, and Sports Illustrated wrote that "his celebrated stride was unmistakable to the crowd. When he came into view, waves of sound began to build throughout the stadium, rising to a roar, then to a thunder. When the national teams, assembled in formation on the infield, saw the flowing figure of Nurmi, they broke ranks like excited schoolchildren, dashing toward the edge of the track."[94] After lighting the flame in the Olympic Cauldron, Nurmi passed the torch to his idol Kolehmainen, who lighted the beacon in the tower.[59] In the cancelled 1940 Summer Olympics, Nurmi had been planned to lead a group of fifty Finnish gold medal winners.[95]

Nurmi felt that he got too much credit as an athlete and too little as a businessman,[9] but his interest in running never died.[96] He even returned to the track himself a few times. In 1946, he faced his old rival Edvin Wide in Stockholm in a benefit for the victims of the Greek Civil War.[97] Nurmi ran for the last time on 18 February 1966 at the Madison Square Garden, invited by the New York Athletic Club.[98] In 1962, Nurmi predicted that welfare countries would start to struggle in the distance events: "The higher the standard of living in a country, the weaker the results often are in the events which call for work and trouble. I would like to warn this new generation: 'Do not let this comfortable life make you lazy. Do not let the new means of transport kill your instinct for physical exercise. Too many young people get used to driving in a car even for small distances.'"[99] In 1966, he took the microphone in front of 300 sports club guests and criticised the state of distance running in Finland, reproaching the sports executives as publicity seekers and tourists, and demanding athletes sacrifice everything to accomplish something.[100] Nurmi lived to see the renaissance of Finnish running in the 1970s, led by athletes such as the 1972 Olympic gold medalists Lasse Virén and Pekka Vasala.[96] He had complimented the running style of Virén, and advised Vasala to concentrate on Kipchoge Keino.[9]

Although he accepted an invitation from President Lyndon B. Johnson to revisit the White House in 1964,[101] Nurmi lived a very secluded life until the late 1960s when he began granting some press interviews.[102] On his 70th birthday, Nurmi agreed to an interview for Yle, Finland's national public-broadcasting company, only after learning that President Kekkonen would act as the interviewer.[103] Suffering from health problems, with at least one heart attack, a stroke and failing eyesight, Nurmi at times spoke bitterly about sports, calling it a waste of time compared to science and art.[104] He died in 1973 in Helsinki and was given a state funeral.[28] Kekkonen attended the funeral and praised Nurmi: "People explore the horizons for a successor. But none comes and none will, for his class is extinguished with him."[59] At the request of Nurmi, who enjoyed classical music and played the violin,[9] Konsta Jylhä's Vaiennut viulu (The Silenced Violin) was played during the ceremony.[105] Nurmi's last record fell in 1996; his 1925 world record for the indoor 2000 m lasted as the Finnish national record for 71 years.[106]

Personal life and public image

Nurmi was married to socialite Sylvi Laaksonen (1907–1968) from 1932 to 1935.[84] Laaksonen, who was not interested in athletics, opposed Nurmi raising their newborn son Matti to be a runner and stated to the Associated Press in 1933, "[H]is concentration on athletics at last forced me to go to the judge for a divorce."[107] Matti Nurmi did become a middle-distance runner, and later a "self-made" businessman.[87] Nurmi's relationship with his son was termed "uneasy".[87] Matti admired his father more as a businessman than as an athlete, and the two never discussed his running career.[87] As a runner, Matti was at his best in the 3000 m, where he equalled his father's time.[87] In the famous race on 11 July 1957 when the "three Olavis" (Salsola, Salonen and Vuorisalo) broke the world record for the 1500 m, Matti Nurmi finished a distant ninth with his personal best, 2.2 seconds slower than his father's world record from 1924.[87] Hollywood actress Maila Nurmi, best known as the horror icon "Vampira", was often referred to as Paavo Nurmi's niece.[108] However, the kinship is not supported by official documents.[108]

Nurmi enjoyed the Finnish sports massage and sauna-bathing traditions, crediting the Finnish sauna for his performances during the Paris heat wave in 1924.[109] He had a versatile diet, although he had practiced vegetarianism between the ages of 15 and 21.[109] Nurmi, who identified as neurasthenic, was known to be "taciturn", "stony-faced" and "stubborn".[9] He was not believed to have had any close friends, but he had occasionally socialized and showed his "sarcastic sense of humour" among the small circles he knew.[9] Acclaimed the biggest sporting figure in the world at his peak,[110] Nurmi was averse to publicity and the media,[9] stating later on his 75th birthday, "[W]orldly fame and reputation are worth less than a rotten lingonberry."[87] French journalist Gabriel Hanot questioned Nurmi's intensive approach to sports and wrote in 1924 that Nurmi "is ever more serious, reserved, concentrated, pessimistic, fanatic. There is such coldness in him and his self-control is so great that never for a moment does he show his feelings."[111] Some contemporary Finns nicknamed him Suuri vaikenija (The Great Silent One),[112] and Ron Clarke noted that Nurmi's persona remained a mystery even to Finnish runners and journalists: "Even to them, he was never quite real. He was enigmatic, sphinx-like, a god in a cloud. It was as if he was all the time playing a role in a drama."[111]

Nurmi was more responsive to his fellow athletes than to the media. He exchanged ideas with sprinter Charley Paddock and even trained with his rival Otto Peltzer.[38][113] Nurmi told Peltzer to forget his opponents: "Conquering yourself is the greatest challenge of an athlete."[38] Nurmi was known to emphasize the importance of psychological strength: "Mind is everything; muscle, pieces of rubber. All that I am, I am because of my mind."[114] Regarding Nurmi's track antics, Peltzer found that "in his impenetrability he was a Buddha gliding on the track. Stopwatch in hand, lap after lap, he ran towards the tape, subject only to the laws of a mathematical table."[115] Marathoner Johnny Kelley, who first met his idol at the 1936 Olympics, said that while Nurmi appeared cold to him at first, the two chatted for quite a while after Nurmi had asked for his name: "He grabbed ahold of me — he was so excited. I couldn't believe it!"[116]

Nurmi's speed and elusive personality led to nicknames such as the "Phantom Finn", the "King of Runners" and "Peerless Paavo",[8][117] while his mathematical prowess and use of a stopwatch led the press to characterize him as a running machine.[119] One newspaperman dubbed Nurmi "a mechanical Frankenstein created to annihilate time."[120] Phil Cousineau noted that "his own innovation — the tactic of pacing himself with a stopwatch — both inspired and troubled people in an era when the robot was becoming symbolic of the modern soulless human being."[120] Among the popular newspaper rumours about Nurmi was that he had a "freakish heart" with a very low pulse rate.[121] During the debate over his amateur status, Nurmi was joked to have "the lowest heartbeat and the highest asking price of any athlete in the world."

Legacy

Nurmi broke 22 official world records on distances between 1500 m and 20 km; a record in running.[15][122] He also set many more unofficial ones for a total of 58.[87] His indoor world records were all unofficial as the IAAF did not ratify indoor records until the 1980s.[15] Nurmi's record for most Olympic gold medals was matched by gymnast Larisa Latynina in 1964, swimmer Mark Spitz in 1972 and fellow track and field athlete Carl Lewis in 1996, and broken by swimmer Michael Phelps in 2008.[123] Nurmi's record for most medals in the Olympic Games stood until Edoardo Mangiarotti won his 13th medal in fencing in 1960.[124] Time selected Nurmi as the greatest Olympian of all time in 1996,[125] and IAAF named him among the first twelve athletes to be inducted into the IAAF Hall of Fame in 2012.[126]

Nurmi introduced the "even pace" strategy to running, pacing himself with a stopwatch and spreading his energy uniformly over the race.[127] He reasoned that "when you race against time, you don't have to sprint. Others can't hold the pace if it is steady and hard all through to the tape." Archie Macpherson stated that "with the stopwatch always in his hand, he elevated athletics to a new plane of intelligent application of effort and was the harbinger of the modern scientifically prepared athlete."[128] Nurmi was considered a pioneer also in regards to training; he developed a systematic all-year-round training program that included both long-distance work and interval running.[129][130] Peter Lovesey wrote in The Kings of Distance: A Study of Five Great Runners that Nurmi "accelerated the progress of world records; developed and actually came to personify the analytic approach to running; and he was a profound influence not only in Finland, but throughout the world of athletics. Nurmi, his style, technique and tactics were held to be infallible, and really seemed so, as successive imitators in Finland steadily improved the records."[81] Cordner Nelson, founder of Track & Field News, credited Nurmi for popularizing running as a spectator sport: "His imprint on the track world was greater than any man’s before or after. He, more than any man, raised track to the glory of a major sport in the eyes of international fans, and they honored him as one of the truly great athletes of all sports."[111]

Nurmi's achievements and training methods inspired future generations of track stars. Emil Zátopek chanted "I am Nurmi! I am Nurmi!" when he trained as a child,[87] and based his training system on what he was able to find out about Nurmi's methods.[131] Lasse Virén idolized Nurmi and was scheduled to meet him for the first time on the day that Nurmi died.[115] Hicham El Guerrouj was inspired to become a runner so that he could "repeat the achievements of the great man of whom his grandfather spoke."[132] He became the first man after Nurmi to win the 1500 m and the 5000 m at the same Games.[132] Nurmi's influence stretched further than running on the Olympic arena. At the 1928 Olympics, Kazimierz Wierzyński won the lyric gold medal with his poem Olympic Laurel that included a verse on Nurmi.[133] In 1936, Ludwig Stubbendorf and his horse Nurmi won the individual and team gold medals in eventing.[133]

A bronze statue of Nurmi was sculpted by Wäinö Aaltonen in 1925.[134] The original is held at the art museum Ateneum, but copies cast from the original mould exist in Turku, in Jyväskylä, in front of the Helsinki Olympic Stadium and at the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland.[134] In a widely publicized prank by the students of the Helsinki University of Technology, a miniature copy of the statue was discovered from the 300-year-old wreck of the Swedish war ship Vasa when it was lifted from the bottom of the sea in 1961.[135] Statues of Nurmi were also sculpted by Renée Sintenis in 1926 and by Carl Eldh, whose 1937 work Löpare (Runners) depicts a battle between Nurmi and Edvin Wide.[133] Boken om Nurmi (The Book about Nurmi), released in Sweden in 1925, was the first biographical book on a Finnish sportsman.[133] Finnish astronomer Yrjö Väisälä named the main belt asteroid 1740 Paavo Nurmi after Nurmi in 1939,[136] while Finnair named its first DC-8 Paavo Nurmi in 1969.[137] Nurmi's former rival Ville Ritola boarded the plane when he moved back to Finland in 1970.[133]

Paavo Nurmi Marathon, held annually since 1969, is the oldest marathon in Wisconsin and the second-oldest in the American Midwest.[138] In Finland, another marathon bearing the name has been held in Nurmi's hometown of Turku since 1992, along with the athletics competition Paavo Nurmi Games that was started in 1957.[139] Finlandia University, an American college with Finnish roots, named their athletic center after Nurmi.[140] A ten-mark bill featuring a portrait of Nurmi was issued by the Bank of Finland in 1987.[141] The other revised bills honored architect Alvar Aalto, composer Jean Sibelius, Enlightenment thinker Anders Chydenius and author Elias Lönnrot, respectively.[141] The Nurmi bill was replaced by a new 20-mark note featuring Väinö Linna in 1993.[141] In 1997, a historic stadium in Turku was renamed the Paavo Nurmi Stadium.[133] Twenty world records have been set at the stadium, including John Landy's records on the 1500 m and the mile, Nurmi's record on the 3000 m and Zátopek's record on the 10,000 m.[142] In fiction, Nurmi appears in William Goldman's 1974 novel Marathon Man as the idol of the protagonist, who aims to become a greater runner than Nurmi.[143] The opera on Nurmi, Paavo the Great. Great Race. Great Dream., written by Paavo Haavikko and composed by Tuomas Kantelinen, debuted at the Helsinki Olympic Stadium in 2000.[144] In a 2005 episode of The Simpsons, Mr. Burns brags that he once outraced Nurmi in his antique motorcar.[145] The NURMI Study, which aims to compare the athletic performance of vegetarian and vegan athletes to those with omnivorous diets, is named in honour of Paavo Nurmi.[146][147]

Career summary (1920–34)

Seasons

The starts figure excludes heats, handicap races, relays, and events where Nurmi raced alone against relay teams.

| Season | Distances | Starts | Wins | Podiums | DNF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 1500 m – 10,000 m[148] | 14 | 13 | 14 | 0 |

| 1921 | 800 m – 10,000 m[149] | 17 | 15 | 16 | 0 |

| 1922 | 800 m – 4 miles[150] | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| 1923 | 800 m – 5000 m[151] | 23 | 23 | 23 | 0 |

| 1924 | 800 m – 10,000 m[152] | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 |

| 1925 | 800 m – 10,000 m[153] | 58 | 56 | 57 | 1 |

| 1926 | 1000 m – 10,000 m[154] | 19 | 16 | 19 | 0 |

| 1927 | 1500 m – 5000 m[155] | 12 | 12 | 12 | 0 |

| 1928 | 1500 m – One hour run[156] | 15 | 12 | 15 | 0 |

| 1929 | Mile – 6 miles[157] | 14 | 12 | 14 | 0 |

| 1930 | 1500 m – 20,000 m[158] | 11 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

| 1931 | 2 miles – 7 miles[159] | 16 | 14 | 14 | 2 |

| 1932 | 10,000 m – Marathon[77] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1933 | 1500 m – 25,000 m[160] | 16 | 13 | 15 | 1 |

| 1934 | 3000 m – 10,000 m[161] | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

Events

The starts figure excludes heats, handicap races, relays, and events where Nurmi raced alone against relay teams.

| Event | Years | Starts | Wins | Podiums | DNF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800 m / 880 yd | 1921–1925[162] | 8 | 6 | 8 | 0 |

| 1500 m | 1920–1933[163] | 33 | 30 | 32 | 0 |

| Mile | 1920–1929[76] | 10 | 9 | 10 | 0 |

| 3000 m | 1920–1934[164] | 29 | 27 | 29 | 0 |

| 2 miles | 1922–1931[165] | 23 | 22 | 23 | 0 |

| 5000 m | 1920–1934[166] | 71 | 67 | 69 | 2 |

| 10,000 m | 1920–1934[79] | 17 | 17 | 17 | 0 |

| Cross country | 1920–1934[80] | 23 | 23 | 23 | 0 |

Olympics

| Year | Date | Event | Mark | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 16 August[11] | 5000 m – heat 3 | 15:33.0 | Q (2nd) |

| 17 August[11] | 5000 m – final | 15:00.5 | 2nd | |

| 19 August[11] | 10,000 m – heat 1 | 33:46.3 | Q (2nd) | |

| 20 August[11] | 10,000 m – final | 31:45.8 | 1st | |

| 22 August[11] | Individual cross country | 27:15.0 | 1st | |

| Team cross country | 10 pts | 1st | ||

| 1924 | 8 July[167] | 5000 m – heat 2 | 15:28.6 | Q (1st) |

| 9 July[167] | 1500 m – heat 3 | 4:07.6 | Q (1st) | |

| 10 July[167] | 1500 m – final | 3:53.6 (OR) | 1st | |

| 5000 m – final | 14:31.2 (OR) | 1st | ||

| 11 July[167] | 3000 m team race – heat 1 | 8:47.8 (1st) | Q (1st) | |

| 12 July[167] | Individual cross country | 32:54.8 | 1st | |

| Team cross country | 11 pts | 1st | ||

| 13 July[167] | 3000 m team race – final | 8:32.0 (1st) | 1st | |

| 1928 | 29 July[168] | 10,000 m | 30:18.8 (OR) | 1st |

| 31 July[168] | 5000 m – heat 3 | 15:08.0 | Q (4th) | |

| 1 August[168] | 3000 m steeplechase – heat 2 | 9:58.8 | Q (1st) | |

| 3 August[168] | 5000 m – final | 14:40.0 | 2nd | |

| 4 August[168] | 3000 m steeplechase – final | 9:31.2 | 2nd |

World records

IAAF-ratified

| Distance | Mark[15] | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1500 m | 3:52.6 | 19 June 1924 | Helsinki |

| Mile | 4:10.4 | 23 August 1923 | Stockholm |

| 2000 m | 5:26.3 | 4 September 1922 | Tampere |

| 2000 m | 5:24.6 | 18 June 1927 | Kuopio |

| 3000 m | 8:28.6 | 27 August 1922 | Turku |

| 3000 m | 8:25.4 | 24 May 1926 | Berlin |

| 3000 m | 8:20.4 | 13 July 1926 | Stockholm |

| 2 miles | 8:59.6 | 24 July 1931 | Helsinki |

| 3 miles | 14:11.2 | 24 August 1923 | Stockholm |

| 5000 m | 14:35.4 | 12 September 1922 | Stockholm |

| 5000 m | 14:28.2 | 19 June 1924 | Helsinki |

| 4 miles | 19:15.4 | 1 October 1924 | Viipuri |

| 5 miles | 24:06.2 | 1 October 1924 | Viipuri |

| 6 miles | 29:36.4 | 8 June 1930 | London |

| 10,000 m | 30:40.2 | 22 June 1921 | Stockholm |

| 10,000 m | 30:06.2 | 31 August 1924 | Kuopio |

| 15000 m | 46:49.6 | 7 October 1928 | Berlin |

| 10 miles | 50:15.0 | 7 October 1928 | Berlin |

| One hour run | 19,210 m | 7 October 1928 | Berlin |

| 20,000 m | 1:04:38.4 | 3 September 1930 | Stockholm |

| 4 × 1500 m | 16:26.2 | 12 July 1926 | Stockholm |

| 4 × 1500 m | 16:11.4 | 17 July 1926 | Viipuri |

Unofficial

| Distance | Mark | Date | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1500 m | 3:53.0[169] | 23 August 1923 | Stockholm |

| 1500 m (indoor) | 3:56.2[170] | 6 January 1925 | New York City |

| Mile (indoor) | 4:13.5[30] | 6 January 1925 | New York City |

| Mile (indoor) | 4:12.0[171] | 7 March 1925 | Buffalo |

| 2000 m (indoor) | 5:33.0[172] | 17 January 1925 | New York City |

| 2000 m (indoor) | 5:30.2[172] | 28 January 1925 | New York City |

| 2000 m (indoor) | 5:22.4[173] | 12 February 1925 | Buffalo |

| 3000 m | 8:27.8[174] | 17 September 1923 | Copenhagen |

| 3000 m (indoor) | 8:26.8[175] | 15 January 1925 | New York City |

| 3000 m (indoor) | 8:26.4[172] | 12 March 1925 | New York City |

| 2 miles (indoor) | 9:08.0[176] | 7 February 1925 | New York City |

| 2 miles (indoor) | 8:58.2[177] | 14 February 1925 | New York City |

| 3 miles | 14:14.4[178] | 10 August 1922 | Kokkola |

| 3 miles | 14:08.4[179] | 12 September 1922 | Stockholm |

| 3 miles | 14:02.0[178] | 19 June 1924 | Helsinki |

| 5000 m (indoor) | 14:44.6[30] | 6 January 1925 | New York City |

| 4 miles | 19:18.8[178] | 31 August 1924 | Kuopio |

| 5 miles | 24:13.2[178] | 31 August 1924 | Kuopio |

| 6 miles | 29:41.2[178] | 22 June 1921 | Stockholm |

| 6 miles | 29:07.1[178] | 31 August 1924 | Kuopio |

| 25-mile marathon | 2:22:03.8[57] | 26 June 1932 | Viipuri |

See also

References

- "Paavo Nurmi". sports-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Paavo Nurmi at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Paavo Nurmi". olympic.org. International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Railo, Raimo. "Legendaarinen Paavo Nurmi – sata vuotta ja ylikin suomalaista urheilua, osa 11" [The legendary Paavo Nurmi – over one hundred years of Finnish sport, part 11]. Suomen Liikunta ja Urheilu (SLU) (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Paavo Nurmi's home". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Luhtala, Seppo (2002). Top Distance Runners of the Century. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. p. 15. ISBN 978-1841260693.

- Sears 2001, pp. 212–213.

- "Paavo Nurmi – A biography". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Autio, Veli-Matti (12 September 1997). "Nurmi, Paavo (1897–1973)". Finnish Literature Society (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Hänninen, Petri (13 June 2017). "Kaikki juoksijalegenda Paavo Nurmen värikkäästä elämästä – maailmanennätysten tehtailijasta kovaksi liikemieheksi". Yle. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 432.

- "Paavo Nurmi at the Olympic Games – Antwerp 1920". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 98.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 99.

- "Paavo Nurmi's world records (approved by the IAAF)". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Pesola, Matti. "SUL 100 vuotta – Paavo Nurmi" [SUL 100 years – Paavo Nurmi]. Elite Games (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 97.

- "Paavo Nurmi at the Olympic Games – Paris 1924". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Robinson, Roger. "The Greatest Races". Running Times (Apr 2008): 48.

- Sears 2001, p. 214.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 174.

- "Paavo Nurmi : makes the impossible possible". International Olympic Committee. 13 June 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- Burnton, Simon (18 May 2012). "50 stunning Olympic moments No31: Paavo Nurmi wins 5000m in 1924". The Guardian.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 177–178.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 111.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 179.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 112.

- "Paavo Nurmi". CNN. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 417.

- "The American Tour of 1925". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Alan Helffrich Hands Paavo Nurmi His First Defeat in Five Years". The Meriden Daily Journal. 27 May 1925. p. 8. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 433–439.

- Autio, Veli-Matti; Fletcher, Roderich. "Nurmi, Paavo (1897–1973)". Finnish Literature Society. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Coolidge Talks With Nurmi As They Pose for Pictures". The New York Times. 22 February 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Nurmi says he's never coming back to America". The Lewiston Daily Sun. 21 May 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 258.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 259.

- Pears, Time (29 June 2008). "Otto the strange: The champion who defied the Nazis". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 259–260.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 260–262.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 269.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 428.

- "Paavo Nurmi at the Olympic Games – Amsterdam 1928". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Nurmi Mark Has Been Bettered". Ottawa Citizen. 2 October 1945. p. 15. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Getty, Frank (19 January 1929). "Paavo Nurmi runs tonight in Brooklyn". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 1. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Conger Beats Paavo Nurmi in Mile Run". The Day. 11 February 1929. p. 8. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Ray Conger Named Coach; Noted Track Star to Direct the Teams at Penn State". The New York Times. 24 December 1942. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Paavo May Quit Mile Run". The Milwaukee Journal. 11 February 1929. p. 2. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmi Sets Record". The Milwaukee Journal. 25 July 1931. p. 10. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Quercetani, Roberto (1964). A World History of Track and Field Athletics. Oxford University Press. p. 139.

- "Paavo Nurmi on Finnish team of 25 for Olympics". The Lewiston Daily Sun. 29 December 1931. p. 8. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- "Finns Aroused by Nurmi Suspension". St Petersburg Times. 4 April 1932. p. 7. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmi Cleared of Pro Charges, to Marry". Telegraph Herald. 11 April 1932. p. 9. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Nurmi Hopes To Run in Olympics". The Border Cities Star. 8 June 1932. p. 2. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Martin, David E.; Gynn, Roger W. H. (2000). The Olympic Marathon. Human Kinetics. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0880119696.

- Luhtala, Seppo (2002). Top Distance Runners of the Century. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. p. 13. ISBN 978-1841260693.

- "Paavo Nurmi Claims Mark". San Jose News. 27 June 1932. p. 2. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Gould, Alan (23 July 1932). "U.S. opposes blanket law under I.A.A.F." Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 14. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Sears 2001, p. 216.

- Gould, Alan (29 July 1932). "Paavo Nurmi barred from Olympic meet". Telegraph Herald. p. 11. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Nurmi uncompetitive. Helsingin Sanomat, 4.4.1932, p. 1. HS Aikakone (for subscribers only). Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- Nurmi is not allowed to run at the Olympics. Helsingin Sanomat, 30.7.1932, p. 4. HS Aikakone (subscribers only). Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- The truth about the Nurmi story and how to drive it in America. Helsingin Sanomat, 8.9.1932, p. 4, 7. HS Aikakone (subscribers only). Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- The truth about the Nurmi story and how to drive it in America. Helsingin Sanomat, 9.9.1932, p. 4. HS Aikakone (for subscribers only). Retrieved 2021-09-24.

- "Great Nurmi barred from Olympic Games as teams prepare for big carnival". Reading Eagle. 29 July 1932. p. 19. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Finns Are Fretful Over Nurmi's Case". The Vancouver Sun. 30 July 1932. p. 16. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 280.

- ["usoc"]

- Kekkonen, Urho (9 September 1932). "Totuus Nurmen jutusta ja sen ajamisesta Amerikassa" [The truth about Nurmi's story and how things were handled in America]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Daley, Arthur J. (21 July 1932). "Nurmi Is Ordered to Rest His Leg; Dr. Martin Diagnoses Injury to Finnish Runner as a Pulled Achilles Tendon". The New York Times. p. 20. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmi probably through as amateur". Reading Eagle. 10 August 1932. p. 9. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Finland and Sweden renew old rivalry on the athletics track this weekend". Helsingin Sanomat. 29 August 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Jalava, Juhani (15 March 2005). "1925–1935: Yleisurheilu sai Suomen liikkeelle" [1925–1935: Athletics got the Finnish launch]. Turun Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 289.

- "Won't Turn". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. 28 December 1932. p. 10. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 421.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 443.

- "Athletic Union Denies Nurmi Amateur Rank". Schenectady Gazette. 29 August 1934. p. 14. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 426.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 427.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 165.

- "Paavo Nurmi Resigns as Finnish Instructor". The Milwaukee Journal. 7 May 1935. p. 2. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Nurmi Resumes Coaching Finns". The Gettysburg Times. 2 August 1935. p. 6. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmen herrainvaateliike oli Mikonkadulla" [Paavo Nurmi's clothing store was on Mikonkatu]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 9 September 2006. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Sjoblom, Paul (5 June 1941). "'Phantom Finn' Will Coach Runners". The Calgary Herald. p. 7. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Sandrock, Michael (1996). Running with the Legends. Human Kinetics. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0873224932.

- Gillon, Doug (13 August 2005). "'Nurmi on Nurmi' – son of 'Flying Finn' legend speaks about his father". IAAF. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmi: a majestic runner but one thorny customer as a man". Helsingin Sanomat. 15 August 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Tilden Returns to Tennis For Finnish Relief Fund". The Pittsburgh Press. 2 February 1940. p. 39. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "People, Feb. 12, 1940". Time. 12 February 1940. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 357.

- "Maki Out To Redeem Self". The Pittsburgh Press. 19 April 1940. pp. 2–7. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Railo, Raimo (8 June 2000). "Sata vuotta ja ylikin suomalaista urheilua, 12. osa" [Five years and a lot of Finnish sports, Part 12]. Suomen Liikunta ja Urheilu (SLU) (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 28 September 2003. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Johnson, William (17 July 1972). "After The Golden Moment". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Finns to Pay Tribute to Nurmi at Olympics". The Milwaukee Journal. 28 February 1939. p. 6. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 382.

- Karikko, Paavo; Koski, Mauno (1975). Yksin aikaa vastaan: Paavo Nurmen elämäkerta (in Finnish). Weilin & Göös. p. 310. ISBN 978-9513514075.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 377.

- Phillips, Bob (2005). "Then Snell came past like a runaway horse" (PDF). BMC News. The British Milers' Club. 4 (2): 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 380–381.

- "Paavo Nurmi Welcomed to Washington by President". The New York Times. 25 January 1964. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Famed Nurmi Dies at 73". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 2 October 1973. p. 15. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Nurmi Wants To Meet Jim Ryun". The Palm Beach Post. 14 June 1967. p. 18. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 365.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 415.

- "Nurmi's last record falls, one he set in Buffalo". The Buffalo News. 14 February 1996. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- "Athlete should never marry, says Mrs. Paavo Nurmi". The Calgary Daily Herald. 20 October 1933. p. 8. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Kaseva, Tuomas. "Maila Nurmi". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Nurmi, Paavo (7 July 1932). "Kunnossaolosalaisuuteni. Sauna ja hieronta ihmelääkkeet" [Kunnossaolo-secret. Sauna and massage are the cure for all ills] (PDF). Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Lopez, Enrique Hank (April 1974). "The Shoeless Mexicans Vs. The Flying Finn". American Heritage. 25 (3). Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- "Nurmi as seen by others". The Sports Museum of Finland. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 372.

- Olympic Review, Issues 195–206. International Olympic Committee. 1984. p. 171.

- Pfitzinger, Pete; Douglas, Scott (2008). Advanced Marathoning. Human Kinetics. p. 11. ISBN 978-0736074605.

- Pears, Tim (29 July 2007). "The time machine". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Lewis, Frederick; Johnson, Dick (2005). Young at Heart: The Story of Johnny Kelley, Boston's Marathon Man. Rounder Records. p. 49. ISBN 978-1579401139.

- Sjoblom, Paul (5 June 1941). "Nurmi To Coach Athletes". The Leader-Post. p. 17. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Bale, John (2003). Running Cultures: Racing in Time and Space. Routledge. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0714684246.

- Cousineau, Phil (2003). The Olympic Odyssey: Rekindling the True Spirit of the Great Games. Quest Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0835608336.

- Salsinger, H. G. (5 March 1927). "Courage and Endurance — Matters of Stomach, Not of Heart". The Dearborn Independent. p. 12.

- "Gebrselassie approaching Record for Running Records". IAAF. 16 March 2006. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Schwartz, Larry (13 August 2008). "Phelps cements place in history". BBC. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Martin, Douglas (25 May 2012). "Edoardo Mangiarotti, Olympian Fencer, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 15.

- "Owens, Nurmi among first in IAAF Hall of Fame". Reuters. 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- Kiell, Paul J. (2006). American Miler: The Life and Times of Glenn Cunningham. Breakaway Books. p. 241. ISBN 978-1891369599.

- Macpherson, Archie (13 December 1999). "Sport has become a matter of taste". The Herald. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- "Faster, Higher, Stronger – Paavo Nurmi". BBC. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Nurmi pioneered modern long-distance running". Sports Illustrated. 8 August 2004. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Lovesey 1968, p. 125.

- Bingham, Eugene (30 August 2004). "Athletics: Nurmi legend relived by El Guerrouj". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Peltola, Vesa-Matti. "Huomionosoituksia maassa ja taivaassa" [Accolades down on earth and up on high]. Suomen Urheilutietäjät (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Seiro, Arno (17 November 2009). "Sportsmen set in stone in the capital". Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Ihamäki, Olli (28 April 2011). "Teekkarien kuningasjäynästä puoli vuosisataa" [Half a century of Techak's roar]. Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Schmadel, Lutz (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. p. 138. ISBN 978-3540002383.

- "DC-8 – A big leap forward". Finnair. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Huhti, Thomas (2011). Wisconsin. Avalon Travel. p. 261. ISBN 978-1598807455.

- "Yleisurheilun klassikko Turun kesässä" [An athletics classic in the summer at Turku]. Paavo Nurmi Sports (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Paavo Nurmi Athletic Center". Finlandia University. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Ask about money!". Bank of Finland. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Rimpiläinen, Tuomas (6 October 2010). "Turkuun pystytettiin kirjoitusvirheitä pursuava muistomerkki" [A memorial to writing errors erected in Turku]. Turun Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Lyons, Gene (27 October 1974). "Four novels... [including] Marathon Man by William Goldman. 309 pp. New York: Delacorte Press. $7.95". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Sport and song combine in Paavo Nurmi Opera spectacle". Helsingin Sanomat. 7 August 2000. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "The Simpsons -sarjan tuoreessa olympialaisjaksossa vieraillaan Helsingissä" [The Simpsons in the new Olympic season in Helsinki]. Dome (in Finnish). 16 February 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Wirnitzer, Gerold. "Home". NURMI-Study (in German). Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Wirnitzer, Katharina; Boldt, Patrick; Wirnitzer, Gerold; Leitzmann, Claus; Tanous, Derrick; Motevalli, Mohamad; Rosemann, Thomas; Knechtle, Beat (18 June 2022). "Health status of recreational runners over 10-km up to ultra-marathon distance based on data of the NURMI Study Step 2". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 10295. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1210295W. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13844-4. PMC 9206639. PMID 35717392.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 432–433.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 433.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 433–434.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 434–435.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 436–437.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 437–438.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 439.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 439–440.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 440–441.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 441–442.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 442.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 442–443.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 443–444.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 444.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 419.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 420–421.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 422–423.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 432–444.

- Raevuori 1997, pp. 423–425.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 436.

- Raevuori 1997, p. 440.

- Quercetani, Roberto (1964). A World History of Track and Field Athletics. Oxford University Press. p. 100.

- "3 world records broken by Nurmi on indoor track". Ellensburg Daily Record. 7 January 1925. p. 8. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Nurmi sets record, runs mile in 4:12". The New York Times. 7 March 1925. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Rumbo a Helsinki 2012 – Grandes Atletas Europeos: Capítulo 1 – Non-Champions" (PDF). Real Federación Española de Atletismo. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Nurmi's new records". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 February 1925. p. 17. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Matthews, Peter (1986). Track & Field Athletics: The Records. Guinness Books. p. 15.

- "Nurmi smashes three more world marks". St. Petersburg Times. 16 January 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Ray's last record smashed by Nurmi". The New York Times. 8 February 1925. Retrieved 26 August 2012. (subscription required)

- "Nurmi burns up boards to new two-mile record". The Sunday Morning Star. 15 February 1925. p. 23. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Kolkka, Sulo; Nygrén, Helge (1974). Paavo Nurmi. Otava. pp. 93–94.

- "Nurmi breaks 2 world records". Providence News. 13 September 1922. p. 14. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

Bibliography

- Lovesey, Peter (1968). The Kings of Distance: A Study of Five Great Runners. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-3540002383.

- Raevuori, Antero (1997). Paavo Nurmi, juoksijoiden kuningas (in Finnish) (2nd ed.). WSOY. ISBN 978-9510218501.

- Sears, Edward Seldon (2001). Running Through the Ages. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786409716.

External links

![]() Media related to Paavo Nurmi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paavo Nurmi at Wikimedia Commons