Pandora's box

Pandora's box is an artifact in Greek mythology connected with the myth of Pandora in Hesiod's c. 700 B.C. poem Works and Days.[1] Hesiod related that curiosity led her to open a container left in the care of her husband, thus releasing curses upon mankind. Later depictions of the story have been varied, with some literary and artistic treatments focusing more on the contents than on Pandora herself.

The container mentioned in the original account was actually a large storage jar, but the word was later mistranslated. In modern times an idiom has grown from the story meaning "Any source of great and unexpected troubles",[2] or alternatively "A present which seems valuable but which in reality is a curse".[3]

In mythology

According to Hesiod, when Prometheus stole fire from heaven, Zeus, the king of the gods, took vengeance by presenting Pandora to Prometheus' brother Epimetheus. Pandora opened a jar left in her care containing sickness, death and many other unspecified evils which were then released into the world.[4] Though she hastened to close the container, only one thing was left behind – usually translated as Hope, though it could also have the pessimistic meaning of "deceptive expectation".[5]

From this story has grown the idiom "to open a Pandora's box", meaning to do or start something that will cause many unforeseen problems.[6] A modern, more colloquial equivalent is "to open a can of worms".[7]

Etymology of the "box"

The word translated as "box" was actually a large jar (πίθος pithos) in Greek.[8][9] Pithoi were used for storage of wine, oil, grain or other provisions, or, ritually, as a container for a human body for burying, from which it was believed souls escaped and necessarily returned.[10] Many scholars see a close analogy between Pandora herself, who was made from clay, and the clay jar which dispenses evils.[11]

The mistranslation of pithos is usually attributed to the 16th-century humanist Erasmus who, in his Latin account of the story of Pandora, changed the Greek pithos to pyxis, meaning "box".[12] The context in which the story appeared was Erasmus' collection of proverbs, the Adagia (1508), in illustration of the Latin saying Malo accepto stultus sapit (from experiencing trouble a fool is made wise). In his version the box is opened by Epimetheus, whose name means 'Afterthought' – or as Hesiod comments, "he whom mistakes made wise".[13]

Different versions of the container

.jpg.webp) Nicolò dell'Abate, 1555

Nicolò dell'Abate, 1555 Russian fountain, 1801

Russian fountain, 1801 James Gillray political cartoon, 1809

James Gillray political cartoon, 1809 Pandora by John Gibson, 1899

Pandora by John Gibson, 1899 John William Waterhouse, 1896

John William Waterhouse, 1896

Contents

There were alternative accounts of jars or urns containing blessings and evils bestowed upon humanity in Greek myth, of which a very early account is related in Homer's Iliad:

On the floor of Jove's palace there stand two urns, the one filled with evil gifts, and the other with good ones. He for whom Jove the lord of thunder mixes the gifts he sends, will meet now with good and now with evil fortune; but he to whom Jove sends none but evil gifts will be pointed at by the finger of scorn, the hand of famine will pursue him to the ends of the world, and he will go up and down the face of the earth, respected neither by gods nor men.[14]

In a major departure from Hesiod, the 6th-century BC Greek elegiac poet Theognis of Megara states that

Hope is the only good god remaining among mankind;

the others have left and gone to Olympus.

Trust, a mighty god has gone, Restraint has gone from men,

and the Graces, my friend, have abandoned the earth.

Men's judicial oaths are no longer to be trusted, nor does anyone

revere the immortal gods; the race of pious men has perished and

men no longer recognize the rules of conduct or acts of piety.[15]

The poem seems to hint at a myth in which the jar contained blessings rather than evils. It is confirmed in the new era by an Aesopic fable recorded by Babrius, in which the gods send the jar containing blessings to humans. Rather than a named female, it was a generic "foolish man" (ἀκρατὴς ἄνθρωπος) who opened the jar out of curiosity and let them escape. Once the lid was replaced, only hope remained, "promising that she will bestow on each of us the good things that have gone away." This aetiological version is numbered 312 in the Perry Index.[16]

In the Renaissance, the story of the jar was revisited by two immensely influential writers, Andrea Alciato in his Emblemata (1534) and the Neo-Latin poet Gabriele Faerno in his collection of a hundred fables (Fabulum Centum, 1563). Alciato only alluded to the story while depicting the goddess Hope seated on a jar in which, she declares, "I alone stayed behind at home when evils fluttered all around, as the revered muse of the old poet [Hesiod] has told you".[17] Faerno's short poem also addressed the origin of hope but in this case it is the remainder of the "universal blessings" (bona universa) that have escaped: "Of all good things that mortals lack,/Hope in the soul alone stays back."[18]

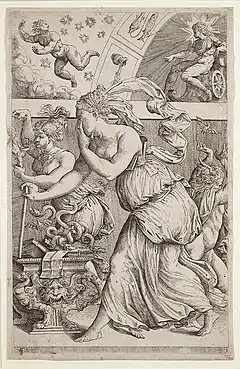

An idea of the nature of the blessings lost is given in a Renaissance engraving by Giulio Bonasone, where the culprit is Pandora's husband, Epimetheus. He is shown holding the lid of a large storage jar from which female representations of the Roman virtues are flying up into the air. They are identified by their names in Latin: security (salus), harmony (concordia), fairness (aequitas), mercy (clementia), freedom (libertas), happiness (felicitas), peace (pax), worth (virtus) and joy (laetitia). Hope (spes) is delayed on the lip and holds aloft the flower that is her attribute.[19]

Difficulties of interpretation

In Hesiodic scholarship, the interpretive crux has endured:[20] Is the hope imprisoned within a jar full of evils to be considered a benefit for humanity, or a further curse? A number of mythology textbooks echo the sentiments of M. L. West: "[Hope's retention in the jar] is comforting, and we are to be thankful for this antidote to our present ills."[21] Some scholars such as Mark Griffith, however, take the opposite view: "[Hope] seems to be a blessing withheld from men so that their life should be the more dreary and depressing."[22] The interpretation hangs on two related questions: First, how is elpis to be rendered, the Greek word usually translated as "hope"? Second, does the jar preserve elpis for men, or keep it away from men?

As with most ancient Greek words, elpis can be translated in a number of ways. A number of scholars prefer the neutral translation of "expectation". Classical authors use the word elpis to mean "expectation of bad", as well as "expectation of good". Statistical analysis demonstrates that the latter sense appears five times more than the former in all of extant ancient Greek literature.[23] Others hold the minority view that elpis should be rendered "expectation of evil" (vel sim).[24]

The answer to the first question largely depends on the answer to the second one: should the jar be interpreted as a prison, or a pantry?[25] The jar certainly serves as a prison for the evils that Pandora released – they only affect humanity once outside the jar. Some have argued that logic dictates, therefore, that the jar acts as a prison for elpis as well, withholding it from the human race.[26] If elpis means expectant hope, then the myth's tone is pessimistic: All the evils in the world were scattered from Pandora's jar, while the one potentially mitigating force, hope, remains locked securely inside.[27] A less pessimistic interpretation understands the myth to say: countless evils fled Pandora's jar and plague human existence; the hope that humanity might be able to master these evils remains imprisoned inside the jar. Life is not hopeless, but human beings are hopelessly human.[28]

It is also argued that hope was simply one of the evils in the jar, the false kind of hope, and was no good for humanity, since, later in the poem, Hesiod writes that hope is empty (498) and no good (500) and makes humanity lazy by taking away their industriousness, making them prone to evil.[29]

In Human, All Too Human, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche argued that "Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man's torment."[30]

An objection to the "hope is good/the jar is a prison" interpretation counters that, if the jar is full of evils, then what is expectant hope – a blessing – doing among them? This objection leads some to render elpis as the expectation of evil, which would make the myth's tone somewhat optimistic: although mankind is troubled by all the evils in the world, at least it is spared the continual expectation of evil, which would make life unbearable.[24]

The optimistic reading of the myth is expressed by M. L. West. Elpis takes the more common meaning of expectant hope. And while the jar served as a prison for the evils that escaped, it thereafter serves as a residence for Hope. West explains, "It would be absurd to represent either the presence of ills by their confinement in a jar or the presence of hope by its escape from one."[31] Hope is thus preserved as a benefit for humans.[32]

Fixing the blame

Neither Alciato nor Faerno had named who was responsible for opening the jar beyond saying it was a "mortal". During the Renaissance it is the name of Epimetheus that is mentioned as often as not, as in the engraving by Bonasone noticed above and the mention of Pandora's partner in a rondeau that Isaac de Benserade took it on himself to insert into his light-hearted version of the Metamorphoses (1676) - although Ovid had not in fact written about it himself.

In a jar an odious treasure is

Shut by the gods' wish:

A gift that's not everyday,

The owner's Pandora alone;

And her eyes, this in hand,

Command the best in the land

As she flits near and far;

Prettiness can't stay

Shut in a jar.

Someone took her eye, he took

A look at what pleased her so

And out came the grief and woe

We won't ever be rid of,

For heaven had hidden

That in the jar.

The etching by Sébastien Le Clerc that accompanied the poem in the book shows Pandora and Epimetheus seated on either side of a jar from which clouds of smoke emerge, carrying up the escaping evils. The lid of the jar is quite plainly in Epimetheus' hand.[33] Paolo Farinati, an earlier Venetian artist, was also responsible for a print which laid the blame on Epimetheus, depicting him as lifting the lid from the jar that Pandora is holding. Out of it boils a cloud which carries up a man and a dragon; between them they support a scroll reading "sero nimirum sapere caepit" (finding out too late), in reference to the meaning of Epimetheus' name in Greek.

Another Venetian print, ascribed to Marco Angelo del Moro (active 1565 – 1586), is much more enigmatic. Usually titled "Pandora's Box, or The Sciences that Illuminate the Human Spirit", it portrays a woman in antique dress opening an ornate coffer from which spill books, manuscripts, snakes and bats. By Pandora's side is a woman carrying a burning brand, while a horned figure flees in the opposite direction. Above is a curved vault painted with signs of the zodiac to which the sun-god Apollo is pointing, while opposite him another figure falls through the stars. Commentators ascribe different meanings to these symbols as contradictory as the contents of the chest. In one reading, the hand Pandora holds up to her face makes her the figure of Ignorance.[34] Alternatively her eyes are protected because she is dazzled and the snakes crawling from the chest are ancient symbols of wisdom.[35] Apollo, seated above, points to Aquarius, the zodiacal sign of January/February, which marks the "Ascent of the Sun" from the trough of winter. The falling figure opposite him may be identified either as Lucifer or as night fleeing before the dawn; in either case, the darkness of ignorance is about to be dispelled. The question remains whether the box thus opened will in the end be recognised as a blessing; whether the ambiguous nature of knowledge is either to help or to hurt.

In later centuries the emphasis in art has generally been on the person of Pandora. With few exceptions, the box has appeared merely as her attribute. René Magritte's street scene of 1951, however, one of the few modern paintings to carry the title "Pandora's Box", is as enigmatic as were the Renaissance allegorical prints.[36]

Theatre

In the first half of the 18th-century, three French plays were produced with the title "Pandora's Box" (La Boîte – or Boëte – de Pandore). In each of these, the main interest is in the social and human effects of the evils released from the box and in only one of them does Pandora figure as a character. The 1721 play by Alain René Lesage appeared as part of the longer La Fausse Foire.[37] It was a one-act prose drama of 24 scenes in the commedia dell'arte style. At its opening, Mercury has been sent in the guise of Harlequin to check whether the box given by Jupiter to the animated statue Pandora has been opened. He proceeds to stir up disruption in her formerly happy village, unleashing ambition, competition, greed, envy, jealousy, hatred, injustice, treachery and ill-health. Amid the social breakdown, Pierrot falls out with the bride he was about to marry at the start of the play and she becomes engaged instead to a social upstart.

The play by Philippe Poisson (1682-1743) was a one-act verse comedy first produced in 1729. There Mercury visits the realm of Pluto to interview the ills shortly to be unleashed on mankind. The characters Old Age, Migraine, Destitution, Hatred, Envy, Paralysis, Quinsy, Fever and Transport (emotional instability) report their effects to him. They are preceded by Love, who argues that he deserves to figure among them as a bringer of social disruption.[38] The later play of 1743 was written by Pierre Brumoy and subtitled "curiosity punished" (la curiosité punie).[39] The three-act satirical verse comedy is set in the home of Epimetheus and the six children recently created by Prometheus. Mercury comes on a visit, bringing the fatal box with him. In it are the evils soon to subvert the innocence of the new creations. Firstly seven flatterers: the Genius of Honours, of Pleasures, Riches, Gaming (pack of cards in hand), Taste, Fashion (dressed as Harlequin) and False Knowledge. These are followed by seven bringers of evil: envy, remorse, avarice, poverty, scorn, ignorance and inconstancy. The corrupted children are rejected by Prometheus but Hope arrives at the end to bring a reconciliation.

It is evident from these plays that, in France at least, blame had shifted from Pandora to the trickster god who contrives and enjoys mankind's subversion. Although physical ills are among the plagues that visit humanity, greater emphasis is given to the disruptive passions which destroy the possibility of harmonious living.

Poetry

Two poems in English dealing with Pandora's opening of the box are in the form of monologues, although Frank Sayers preferred the term monodrama for his recitation with lyrical interludes, written in 1790. In this Pandora is descending from Heaven after being endowed with gifts by the gods and therefore feels empowered to open the casket she carries, releasing strife, care, pride, hatred and despair. Only the voice of Hope is left to comfort her at the end.[40] In the poem by Samuel Phelps Leland (1839-1910), Pandora has already arrived in the household of Epimetheus and feels equally confident that she is privileged to satisfy her curiosity, but with a worse result. Shutting the lid too early, she thus "let loose all curses on mankind/ Without a hope to mitigate their pain".[41] This is the dilemma expressed in the sonnet that Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote to accompany his oil painting of 1869–71. The gifts with which Pandora has been endowed and that made her desirable are ultimately subverted, "the good things turned to ill…Nor canst thou know/ If Hope still pent there be alive or dead."[42] In his painting Rossetti underlines the point as a fiery halo streams upward from the opening casket on which is inscribed the motto NESCITUR IGNESCITUR (unknown it burns).

While the speakers of the verse monologues are characters hurt by their own simplicity, Rossetti's painting of the red-robed Pandora, with her expressive gaze and elongated hands about the jewelled casket, is a more ambiguous figure. So too is the girl in Lawrence Alma-Tadema's watercolour of Pandora (see above), as the comments of some of its interpreters indicate. Sideways against a seascape, red-haired and naked, she gazes down at the urn lifted towards her "with a look of animal curiosity", according to one contemporary reviewer,[43] or else "lost in contemplation of some treasure from the deep" according to another account.[44] A moulded sphinx on the unopened lid of the urn is turned in her direction. In the iconography of the time, such a figure is usually associated with the femme fatale,[45] but in this case, the crown of hyacinths about her head identifies Pandora as an innocent Greek maiden.[46] Nevertheless, the presence of the sphinx at which she gazes with such curiosity suggests a personality on the cusp, on the verge of gaining some harmful knowledge that will henceforth negate her uncomplicated qualities. The name of Pandora already tells her future.

Notes

- Hesiod, Works and Days. 47ff. Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Chambers Dictionary, 1998

- Brewer's Concise Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, 1992

- Cf. Hesiod, Works and Days, (90). "For ere this the tribes of men lived on earth remote and free from ills and hard toil and heavy sicknesses which bring the Fates upon men ... Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within under the rim of the great jar, and did not fly out at the door; for ere that, the lid of the jar stopped her, by the will of Aegis-holding Zeus who gathers the clouds. But the rest, countless plagues, wander amongst men; for earth is full of evils and the sea is full. Of themselves diseases come upon men continually by day and by night, bringing mischief to mortals silently; for wise Zeus took away speech from them."

- Brill's Companion to Hesiod, Leiden NL 2009, p.77 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English". Archived from the original on 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- Ammer, Christine (2013). The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms, Second Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-547-67658-6.

- Schlegel and Weinfield, "Introduction to Hesiod" p. 6

- Meagher 2314, p. 148

- Cf. Harrison, Jane Ellen, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek history, Chapter II, "The Pithoigia", pp.42-43. Cf. also Figure 7 which shows an ancient Greek pot painting in the University of Jena where Hermes is presiding over a body in a pithos buried in the ground. "In the vase painting in fig.7 from a lekythos in the University Museum of Jena we see a Pithoigia of quite other and solemn booty. A large pithos is sunk deep into the ground. It has served as a grave. ... The vase-painting in fig. 7 must not be regarded as an actual conscious representation of the rupent rite performed on the first day of the Anthesteria. It is more general in content; it is in fact simply a representation of ideas familiar to every Greek, that the pithos was a grave-jar, that from such grave-jars souls escaped and to them necessarily returned, and that Hermes was Psychopompos, Evoker and Revoker of souls. The vase-painting is in fact only another form of the scene so often represented on Athenian white lekythoi, in which the souls flutter round the grave-stele. The grave-jar is but the earlier form of sepulture; the little winged figures, the Keres, are identical in both classes of vase-painting."

- Cf. Jenifer Neils 2005, p.41 especially: "They ignore, however, Hesiod's description of Pandora's pithos as arrektoisi or unbreakable. This adjective, which is usually applied to objects of metal, such as gold fetters and hobbles in Homer (Il. 13.37, 15.20), would strongly imply that the jar is made of metal rather than earthenware, which is obviously capable of being broken."

- Meagher 1995, p. 56. In his notes to Hesiod's Works and Days (p.168) M.L. West has surmised that Erasmus may have confused the story of Pandora with that found elsewhere of a box which was opened by Psyche.

- William Watson Baker, The Adages of Erasmus, University of Toronto 2001, 1 i 31, p.32

- Iliad, 24:527ff Archived 2020-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Theognis, 1135ff.

- "Aesopica". Archived from the original on 2018-12-05. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "In simulachrum spei". Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- Fabulum Centum, London 1743, Fable 94, p.216 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Metropolitan Museum". Archived from the original on 2021-01-24. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- Though Pandora was not a subject of medieval art, Dora Panofsky and Erwin Panofsky examined the post-Renaissance mythos, see Bibliography

- West 1978, p. 169.

- Griffith 1983:250.

- Leinieks 1984, 1–4.

- E.g., Verdenius 1985; Blumer 2001.

- The prison/pantry terminology comes from Verdenius 1985 ad 96.

- Scholars holding this view (e.g., Walcot 1961, 250) point out that the jar is termed an "unbreakable" (in Greek: arrektos) house. In Greek literature (e.g., Homer, and elsewhere in Hesiod), the word arrektos is applied to structures meant to sequester or otherwise restrain its contents.

- See Griffith 1984 above.

- Thus Athanassakis 1983 in his commentary ad Works 96.

- Cf. Jenifer Neils, in The Girl in the Pithos: Hesiod's Elpis, in "Periklean Athens and its Legacy. Problems and Perspectives" Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 40–41 especially.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich, Human, All Too Human. Cf. Section Two, On the History of Moral Feelings, aph. 71. "Hope. Pandora brought the jar with the evils and opened it. It was the gods' gift to man, on the outside a beautiful, enticing gift, called the 'lucky jar.' Then all the evils, those lively, winged beings, flew out of it. Since that time, they roam around and do harm to men by day and night. One single evil had not yet slipped out of the jar. As Zeus had wished, Pandora slammed the top down and it remained inside. So now man has the lucky jar in his house forever and thinks the world of the treasure. It is at his service; he reaches for it when he fancies it. For he does not know that the jar which Pandora brought was the jar of evils, and he takes the remaining evil for the greatest worldly good—it is hope, for Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man's torment."

- West 1978, 169–70.

- Taking the jar to serve as a prison at some times and as a pantry at others will also accommodate another pessimistic interpretation of the myth. In this reading, attention is paid to the phrase moune Elpis – "only hope," or "hope alone." A minority opinion construes the phrase instead to mean "empty hope" or "baseless hope": not only are humans plagued by a multitude of evils, but they persist in the fruitless hope that things might get better. Thus Beall 1989 227–28.

- Panofsky 1956, p.79 Archived 2020-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- "Smith College". Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- Count Leopoldo Cicognara, Le premier siècle de la calcographie; ou, Catalogue raisonné des estampes, Venice 1837, pp.532-3 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Yale University Art Gallery". Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- Oeuvres choisies de Lesage, Paris 1810, vol.4, pp.409 – 450 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Théâtre Classique" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- Brumoy, Pierre (1743). "La Haye 1743". Archived from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- Poems, Norwich 1803, pp.213-19 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Poems, Chicago 1866, pp.24-5 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Rossetti Archive

- The Pall Mall Budget 1882, vol. 27, p.14 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- The Life and Work of L. Alma Tadema, Art Journal Office, 1888, p.22

- Lothar Hönnighausen, Präraphaeliten und Fin de Siècle, Cambridge University 1988, pp.232-40 Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Victoria Sherrow, Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History, Greenwood Publishing Group 2006, A Archived 2023-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Athanassakis, Apostolos, Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days and The Shield of Heracles. Translation, introduction and commentary, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1983. Cf. P.90

- Beall, E. "The Contents of Hesiod's Pandora Jar: Erga 94–98," Hermes 117 (1989) 227–30.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Griffith, Mark. Aeschylus Prometheus Bound Text and Commentary (Cambridge 1983).

- Hesiod; Works and Days, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Lamberton, Robert, Hesiod, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-04068-7. Cf. Chapter II, "The Theogony", and Chapter III, "The Works and Days", especially pp. 96–103 for a side-by-side comparison and analysis of the Pandora story.

- Leinieks, V. "Elpis in Hesiod, Works and Days 96," Philologus 128 (1984) 1–8.

- Meagher, Robert E.; The Meaning of Helen: in Search of an Ancient Icon, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1995. ISBN 978-0-86516-510-6.

- Neils, Jenifer, "The Girl in the Pithos: Hesiod's Elpis", in Periklean Athens and its Legacy. Problems and Perspective, eds. J. M. Barringer and J. M. Hurwit (Austin: University of Texas Press), 2005, pp. 37–45.

- Panofsky, Dora and Erwin. Pandora's Box. The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol (New York: Pantheon, Bollingen series) 1956.

- Revard, Stella P., "Milton and Myth" in Reassembling Truth: Twenty-first-century Milton, edited by Charles W. Durham, Kristin A. Pruitt, Susquehanna University Press, 2003. ISBN 9781575910628.

- Rose, Herbert Jennings, A Handbook of Greek Literature; From Homer to the Age of Lucian, London, Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1934. Cf. especially Chapter III, Hesiod and the Hesiodic Schools, p. 61

- Schlegel, Catherine and Henry Weinfield, "Introduction to Hesiod" in Hesiod / Theogony and Works and Days, University of Michigan Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-472-06932-3.

- Verdenius, Willem Jacob, A Commentary on Hesiod Works and Days vv 1-382 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1985). ISBN 90-04-07465-1. This work has a very in-depth discussion and synthesis of the various theories and speculations about the Pandora story and the jar. Cf. p. 62 & 63 and onwards.

- West, M. L. Hesiod, Works and Days, ed. with prolegomena and commentary (Oxford 1978)

External links

![]() Media related to Pandora at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pandora at Wikimedia Commons