Pearl hunting

Pearl hunting, also known as pearling, is the activity of recovering pearls from wild molluscs, usually oysters or mussels, in the sea or freshwater. Pearl hunting was prevalent in the Persian Gulf region and Japan for thousands of years. On the northern and north-western coast of Western Australia pearl diving began in the 1850s, and started in the Torres Strait Islands in the 1860s, where the term also covers diving for nacre or mother of pearl found in what were known as pearl shells.

In most cases the pearl-bearing molluscs live at depths where they are not manually accessible from the surface, and diving or the use of some form of tool is needed to reach them. Historically the molluscs were retrieved by freediving, a technique where the diver descends to the bottom, collects what they can, and surfaces on a single breath. The diving mask improved the ability of the diver to see while underwater. When the surface-supplied diving helmet became available for underwater work, it was also applied to the task of pearl hunting, and the associated activity of collecting pearl shell as a raw material for the manufacture of buttons, inlays and other decorative work. The surface supplied diving helmet greatly extended the time the diver could stay at depth, and introduced the previously unfamiliar hazards of barotrauma of ascent and decompression sickness.

History

.jpg.webp)

Before the beginning of the 20th century, the only means of obtaining pearls was by manually gathering very large numbers of pearl oysters or mussels from the ocean floor or lake or river bottom. The bivalves were then brought to the surface, opened, and the tissues searched. More than a ton were searched in order to find at least 3-4 quality beads.

In order to find enough pearl oysters, free-divers were often forced to descend to depths of over 100 feet on a single breath, exposing them to the dangers of hostile creatures, waves, eye damage, and drowning, often as a result of shallow water blackout on resurfacing.[1] Because of the difficulty of diving and the unpredictable nature of natural pearl growth in pearl oysters, pearls of the time were extremely rare and of varying quality.

Asian

_-_Copy.jpg.webp)

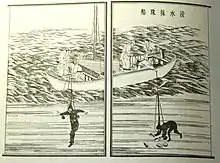

In Asia, some pearl oysters could be found on shoals at a depth of 5–7 feet (1.5–2.1 meters) from the surface, but more often divers had to go 40 feet (12 meters) or even up to 125 feet (38 meters) deep to find enough pearl oysters, and these deep dives were extremely hazardous to the divers. In the 19th century, divers in Asia had only very basic forms of technology to aid their survival at such depths. For example, in some areas they greased their bodies to conserve heat, put greased cotton in their ears, wore a tortoise-shell clip to close their nostrils, gripped a large object like a rock to descend without the wasteful effort of swimming down, and had a wide-mouthed basket or net to hold the oysters.[1][3]

For thousands of years, most seawater pearls were retrieved by divers working in the Indian Ocean, in areas such as the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and in the Gulf of Mannar (between Sri Lanka and India).[4] A fragment of Isidore of Charax's Parthian itinerary was preserved in Athenaeus's 3rd-century Sophists at Dinner, recording freediving for pearls around an island in the Persian Gulf.[5]

Pearl divers near the Philippines were also successful at harvesting large pearls, especially in the Sulu Archipelago. In fact, pearls from the Sulu Archipelago were considered the "finest of the world" which were found in "high bred" shells in deep, clear, and rapid tidal waters. At times, the largest pearls belonged by law to the sultan, and selling them could result in the death penalty for the seller. Nonetheless, many pearls made it out of the archipelago by stealth, ending up in the possession of the wealthiest families in Europe.[6] Pearling was popular in Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Japan, India and some areas in Persian Gulf countries. The Gulf of Mexico was particularly famous for pearling, which was originally found by the Spanish explorers.

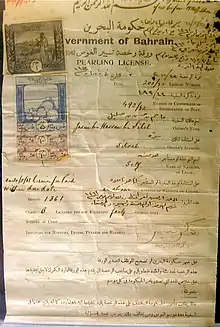

Persian Gulf

The shallow Persian Gulf produced many pearls, and the pearling industry flourished in Kuwait, UAE, and Qatar, with Bahrain producing the highest export. The price for pearls increased throughout the nineteenth century, with the pearl trade expanding in this region. At this time, pearls from the Persian Gulf were being traded in Aleppo and Istanbul, and there is evidence that merchants would sail to India (particularly Bombay) to sell pearls. By the 1930s, there were a few traders travelling all the way to Paris to sell their pearls. In the early twentieth century, it was estimated that about a quarter of the population living in the Persian Gulf's littoral was involved with the pearl trade. In the Persian Gulf, the pearling industry was dominated by slave labor, and male slaves were used as pearl divers[7] until the final abolition of slavery in the Gulf states in the period of 1937-1971.

The pearling industry in this region reached its zenith around 1912, "the Year of Superabundance." By the 1950s, however, dependency on pearls was replaced by dependency on oil, as oil was discovered and the oil industry became the dominant economic trade. [8]

Americas

In a similar manner as in Asia, Native Americans harvested freshwater pearls from lakes and rivers like the Ohio, Tennessee, and Mississippi, while others successfully retrieved marine pearls from the Caribbean and waters along the coasts of Central and South America.

In the time of colonial slavery in northern South America (off the northern coasts of modern Colombia and Venezuela), slaves were used as pearl divers.[9] A diver's career was often short-lived because the waters being searched were known to be shark-infested, resulting in frequent attacks on divers. However, a slave who discovered a great pearl could sometimes purchase his freedom.[10]

The Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s made it hard to get good prices for pearl shell. The natural pearls found from harvested oysters were a rare bonus for the divers. Many fabulous specimens were found over the years. By the 1930s, over-harvesting had severely depleted the oyster beds. The US government was forced to strictly regulate the harvest to prevent the oysters from becoming extinct, and the Mexican government banned all pearl harvesting from 1942 to 1963.[11]

Australia

Although harvesting of shells had long been practiced by Aboriginal Australians, pearl diving only began in the 1850s off the coast of Western Australia and the pearling industry remained strong until the advent of World War I, when the price of mother-of-pearl plummeted with the invention and expanded use of plastics for buttons and other articles previously been made of shell.

In the 1870s pearling began in the Torres Strait, off Far North Queensland. By the 1890s, pearling was the largest industry in the region, and had a huge impact on coastal Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Because of the dangers of diving, almost no white people participated, and Asian, Pacific, and Indigenous Australians were used as cheap labor for the industry. Shells were the main aim for collection, and the whole industry was essentially a colonial one geared to procuring mother-of-pearl for sale to overseas markets for the making of buttons. As time went on and sources were depleted, divers were encouraged to dive deeper, making the enterprise even more dangerous. Divers experimented with the heavy diving suit, discarding the full diving suit and using the helmet and corselet only, which became standard practice until 1960. "Hookah" gear, tested to 48 fathoms (87 metres) in 1922, was considered unsuitable for the strong tides in these waters, and the later Scuba equipment did not supply enough air to spend the time required underwater and for decompression while surfacing [12]

Colonial Latin America

During the first half of the sixteenth century, Spaniards discovered the extensive pearl oyster beds that existed on the Caribbean coast of Venezuela, particularly in the vicinity of Margarita Island. Indigenous slavery was easy to establish in this area because it had not yet been outlawed; therefore, indigenous peoples were captured and often forced to work as pearl divers. Since violence could not protect the efficiency of the slave trade, coastal chieftains established a ransoming system known as the "rescate" system.

As this system continued to grow, more and more oyster beds were discovered along the Latin American coast, including near Riohacha on Colombia's Guajira Peninsula. However, due to over-exploitation of both indigenous labor and the oyster beds, the Spanish pearl economy soon plummeted. By 1540, previous Spanish settlements along the coast had been abandoned as the Spanish looked elsewhere for more labor and newer markets. The pearl industry was partially revived in the late sixteenth century when Spaniards replaced indigenous labor with African slave labor.[13]

Process

Oyster harvesting methods remained much the same along the coast and varied depending on the divers' conditions, the region's topography, and a Spanish master's work demands.

Venezuela

On Margarita Island, small zones were inspected in advance by the divers, who relied on breath-hold endurance to dive and resurface. Once those small zones had been depleted of their oysters, the men on the boat - which usually included a dozen divers, a Spanish navigator, a diving chief, oarsmen, and a foreman - moved on to the next oyster bed. To retrieve the pearls, the divers carried a small net that had one end tied to the boat and the other end tied to the fishing net. The shells that they extracted were usually placed in this basket, but for dives of greater depth, the divers also had to wear stones tied to their bodies as they submerged into the ocean. The stones acted as a ballast until they resurfaced, where the divers then untied the stones from their bodies. The divers would receive a slight break to eat and rest and continue this work until sundown, where they all presented their catch to the foreman, return to the ranchería to have some dinner, and then open the oyster shells.[14]

The divers were locked in their quarters at night by the Spaniards, who believed that if the divers (who were mostly male) compromised their chastity, they would not be able to submerge but rather float on the water. The divers who either had a small catch or rebelled were beaten with whips and tied in shackles. The working day lasted from dawn till dusk and being underwater, along with bruises, could affect the health of some divers. Furthermore, it is well known that the coastal waters were often infested with sharks, so shark attacks were quite frequent as well. As the fisheries continued to diminish, slaves hid some of the valuable pearls and exchanged them for clothing with their bosses.[14]

On Cubagua, another Venezuelan island, the Spaniards used natives as slave labor in their initial attempts to establish a thriving pearl market in this area. Indians, especially those from Lucayo in the Bahamas, were taken as slaves to Cubagua since their diving skills and swimming capabilities were known to be superb. Likewise, the Spaniards began to import African slaves as the indigenous populations died off from disease and over-exploitation and Africans became so preferred by the Spanish over indigenous labor that a royal decree of 1558 decreed that only Africans (and no natives) should be used for pearl diving. Like other pearl diving groups controlled by the Spanish, the pearl divers could be treated harshly based on their daily pearl retrieval. Unlike the other pearl diving groups, however, the divers on Cubagua were marked by a hot iron on their face and arms with the letter "C," which some scholars argue stood for Cubagua.[15]

The pearl diving process in Cubagua varied slightly from other Spanish pearl diving practices. Here, there were six divers per boat and divers worked together in pairs to collect the pearls. These pearl divers used small pouches tied to their necks to collect the oysters from the sea bottom. Some scholars have reported that because of the climate in Cubagua, the heat would cause the oysters to open themselves, making the pearl extraction process a bit simpler. Natives, unlike Africans, were given less rest time and could potentially be thrown off the boat or whipped to commence work sooner. Similar to slaves on Margarita Island, all pearl diving slaves were chained at night to prevent escape; in addition, deaths not only resulted from shark attacks, but also from hemorrhaging caused by rapid surfacing from the water and intestinal issues induced by constant reentry into cold water.[15]

Panama

Diver groups in the Panamanian fisheries were larger than those on Margarita Island, usually comprising 18 - 20 divers. Instead of net bags, these divers surfaced with oysters under their armpits or even in their mouths, placing their catch in a cloth bag on board the ship. Each diver would continue to submerge until he was out of breath or extremely tired, but also after they had met their fixed quota for the day. Once the bags were full, the divers caught another breath and immediately began pearl extraction aboard the vessel, handing the pearls to the foreman who accounted for both imperfect and perfect pearls. Excess pearls were given to the divers who could sell them to the vessel owner at a just price; in contrast, if the divers did not meet their daily quota, they would either use their reserve pearls to fulfill the quota for the next day or write that amount of pearls into a debt account. Like the Venezuelan divers, the Panamanian divers also faced the danger of shark attacks, although they usually carried knives to defend themselves.[14]

Present

Today, pearl diving has largely been supplanted by cultured pearl farms, which use a process widely popularized and promoted by Japanese entrepreneur Kōkichi Mikimoto. Particles implanted in the oyster encourage the formation of pearls and allow for more predictable production. Today's pearl industry produces billions of pearls every year. Ama divers still work, primarily now for the tourist industry.

Pearl diving in the Ohio and Tennessee rivers of the United States still exists today. Pearling in Highland rivers in Scotland was prohibited in 1995 after the mussel population was driven to near extinction, see Pearl#British Isles.

See also

- Ama (diving) – Japanese pearl divers – female Japanese divers

- Blackbirding

- Fijiri – East Arabian repertoire – vocal music of the Gulf pearl diver

- Culture of Eastern Arabia – Overview of the culture of Eastern Arabia

- Paravar – South Indian caste

- Pearl farming industry in China

- Pearling in Western Australia – Local aquaculture industry

- Zubarah – ruined and deserted town in Qatar – a Qatari pearl fishing and trading port in the 18th and 19th centuries

Bibliography

- Al-Hijji, Yacoub Yusuf (2006). Kuwait and the Sea. A Brief Social and Economic History. Arabian Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9558894-4-8.

- al-Shamlan, Saif Marzooq (2001). Pearling in the Arabian Gulf. A Kuwaiti Memoir. The London Centre of Arab Studies. ISBN 1-900404-19-2.

- Bari, Hubert; Lam, David (2010). Pearls. SKIRA / Qatar Museums Authority. ISBN 978-99921-61-15-9. Especially chapter 4 p. 189-238 The Time of the Great Fisheries (1850-1940)

- Ganter, Regina (1994). The Pearl-Shellers of Torres Strait: Resource Use, Development and Decline, 1860s-1960s. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84547-9.

- George Frederick Kunz: Book of the Pearl (G.F. Kunz was America's leading gemologist and worked for Tiffany's in the beginning of the 20th century)

References

- Rahn, H.; Yokoyama, T. (1965). Physiology of Breath-Hold Diving and the Ama of Japan. United States: National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. p. 369. ISBN 0-309-01341-0. Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "A Ceylon Pearl Merchant". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. London: Wesleyan Mission-House. VI. 1849. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Catelle, W. (1907). "Methods of Fishing". The Pearl: Its Story, Its Charm, and Its Value. Philadelphia & London: J. B. Lippincott Company. p. 171.

- De Silva, K. M. (1995). Volume 2 of History of Ceylon, History of Ceylon: History of Sri Lanka. Peradeniya: Ceylon University Press. p. 56. ISBN 955-589-004-8. OCLC 952216.

- Ἰσίδωρος Χαρακηνός [Isidore of Charax]. Τὸ τῆς Παρθίας Περιηγητικόν [Tò tēs Parthías Periēgētikón, A Journey around Parthia]. c. 1st century AD (in Ancient Greek) in Ἀθήναιος [Athenaeus]. Δειπνοσοφισταί [Deipnosophistaí, Sophists at Dinner], Book III, 93E. c. 3rd century (in Ancient Greek) Trans. Charles Burton Gulick as Athenaeus, Vol. I, p. 403. Harvard University Press (Cambridge), 1927. Accessed 13 Aug 2014.

- Streeter's Pearls and pearling life dedicates a chapter to the Sooloo islands. Streeter was one of the leading and most influential English jewelers in the 19th century and outfitted his own Schooner the Shree-Pas-Sair which he sailed as well and on which he himself went pearl fishing in 1880. (See for illustration of divers on Schooner Pearl fishers obtaining the world's best pearls. Streeter furthermore led a consortium to compete with Baron Rothschild to lease Ruby mines in Burma.

- Suzanne Miers: Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem, p. 265-66

- al-Shamlan, Saif Marzooq (2000). Pearling in the Arabian Gulf: A Kuwaiti Memoir. London: The London Center of Arabic Studies. pp. 16–134.

- Michele Robinson, 'Luxuries that cost human life? Pearls in Early Modern Italy', Refashioning the Renaissance, August 2020

- Rout Jr., Leslie B. (1976-07-30). The African Experience in Spanish America. Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-521-20805-X.

- McDonald-Legg, Christina. "Pearl Diving in Mexico". Travel News, Tips, and Guides - USATODAY.com. USA Today. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Ganter, Regina (21 October 2010). "Pearling". Queensland Historical Atlas. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Restall, Matthew (2011). Latin America in Colonial Times. Cambridge University Press. p. 142.

- Orche, Enrique (2009). "Exploitation of pearl fisheries in the Spanish American colonies". De Re Metallica. 13: 19–33.

- Romero, Aldemaro (1999). "Cubagua's Pearl-Oyster Beds: The First Depletion of a Natural Resource Caused by Europeans in the American Continent". Journal of Political Ecology. 6: 57–78. doi:10.2458/v6i1.21423.