Moving panorama

The moving panorama was an innovation on panoramic painting in the mid-nineteenth century. It was among the most popular forms of entertainment in the world, with hundreds of panoramas constantly on tour in the United Kingdom, the United States, and many European countries. Moving panoramas were often seen in melodramatic plays. It became a new visual element to theatre and helped incorporate a more realistic quality. Not only was it a special effect on stage, but it also served as an ancestor and platform to early cinema.

Background

The word “panorama” is derived from the Greek words “to see” and “all.” Robert Barker, an Irish-born scene painter, coined the term with his first panorama of Edinburgh, displayed in a specially built rotunda in Leicester Square in 1791. This attraction was extremely popular amongst the middle and lower classes for the way it was able to offer the illusion of transport for the viewer to a completely different location that they had most likely never seen.

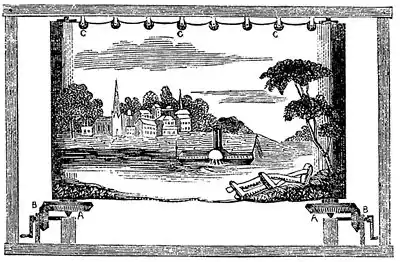

Panoramic paintings and the various offshoots had become so in demand across Europe and America by the early nineteenth century that the enormous paintings had begun to be displayed in less specialized settings, like community halls, churches, and eventually theaters where they evolved into moving panoramas and became essential to theatrical set design. Moving panoramas were achieved by taking the long, continuous painted canvas scene and rolling each end around two large spool-type mechanisms that could be turned, causing the canvas to scroll across the back of a stage, often behind a stationary scenic piece or object like a boat, horse, or vehicle, to create the illusion of movement and travelling through space. The immense spools were scrolled past the audience behind a cut-out drop-scene or proscenium which hid the mechanism from public view. Robert Fulton obtained a patent for the panorama in 1799 in France; he is credited with helping create the spool mechanisms that allowed for the moving panorama to take hold in theatrical set design, combining the technology of the Industrial Revolution and art for profit, very much a nineteenth century idea.

However, these paintings were not true panoramas, but rather contiguous views of passing scenery, as if seen from a boat or a train window. Unlike panoramic painting, the moving panorama almost always had a narrator, styled as its "Delineator" or "Professor", who described the scenes as they passed and added to the drama of the events depicted. One of the most successful of these delineators was John Banvard, whose panorama of a trip up (and down) the Mississippi River had such a successful world tour that the profits enabled him to build an immense mansion, lampooned as "Banvard's Folly", built on Long Island in imitation of Windsor Castle. Banvard was also the first painter to undertake painting a panorama of such size. It was largely the accuracy and sheer spectacle of his Mississippi River panorama that earned him so much fame. In Britain, showmen such as the durable Moses Gompertz toured the provinces with a variety of such panoramas from the 1850s until well into the 1880s.

These moving panoramas were readily accepted in New York, where Americans loved the melodramatic genre of plays, which made use of the newest technologies and relied on spectacle. William Dunlap, America’s first theatre historian, professional playwright, and a painter himself, was commissioned by the Bowery Theatre in New York in 1827 to write, somewhat reluctantly, A Trip to Niagara: or Travellers in America: A Farce, a satirical social comedy, specifically for an already existing painting of a steamboat journey up the Hudson River to the base of Niagara Falls, named the “Eidophusikon.” The production was extremely popular, not for the play, but for the spectacular moving scenery.

The concept of early cinema, “moving pictures,” is a direct evolution of the concept of a moving panorama. The first use of the scrolling background concept early on in film was rear projection. This technique, for example, was used when stationary actors were filming in a car that wasn't actually moving, but instead had a projection of changing locales behind on the rear window to create the illusion that the car was moving, a trope often used in Hitchcock movies. Today, we have much more realistic computer technology to create this illusion of movement, but the image of a stationary object or actor in front of a changing background harkens back to the moving panorama scroll. Moving projections of clouds or passing objects on cycloramas at the back of a stage sometimes seen in modern live theater productions also utilize the illusion of seamless movement behind a stationary object that was popularized by the moving panorama of the nineteenth century.

Popular subjects

Moving panoramas (or sometimes moving dioramas) often recreated grand ceremonies. In Philadelphia in 1811 nearly 1,300 feet (400 m) of painted cloth were unwound to display the Federal Procession of 1788,[1] and George IV's coronation in London was treated as a "Grand Historical Peristrephic Panorama" by the Marshall brothers.[2]

Exotic landscapes and travel were popular themes, particularly trips to India, New Zealand, and the Arctic regions. Popular subjects in America were of river journeys, such as in Dunlap’s Trip to Niagara, and trips out west following the railroads that were quickly springing up as America expanded. Banvard's enormous Mississippi River panorama was shown on both sides of the Atlantic and a moving panorama of "Romantic and Picturesque Scenery in the Environs of Hobart Town" taken to London in 1839 allowed people in England to get an impression of Australia.[3] A narrator explained the scenes passing in front of the audience and music played. In the United States, moving panoramas were popular throughout the 1850s and 1860s, with multiple touring shows operated by proprietors such as Edwin Beale, T.K. Treadwell, Henry Lewis and George K. Goodwin. Among the more popular subjects were the Arctic regions, major cities such as New York, the Mississippi River and Niagara Falls.

Peter Grain's Panorama of the Hudson and James Rivers - Scenes in Virginia, painted in oil and watercolor, was exhibited at the San Francisco Hall in San Francisco in March 1853, concluding a tour of cities across the United States. The work covered 9,400 feet of canvas.

Popular, too, were religious subjects. In the 1877 Bureau County, Illinois, Voter's and Tax Payers,[4] page 361, William Mercer's possessions include two religious themed panoramas. "The Great Apocalypse, containing fifty-two fine oil paintings; " The Visions of St. John," covering 8,000 feet of canvas, and costing $7,000." Mercer sold them to a Kansas firm which exhibited them in 1899. The Visions of St. John 8,000 feet of canvas was a moving panorama of the biblical apocalypse. In 2016, the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign unveiled a display of part of a rare moving panorama which portrays the Annunciation, in which the angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary that she will become the mother of Jesus.

Detail of sequins and gold foil on Marcus Mote’s Scenes from the Life of Christ distemper on cotton muslin.

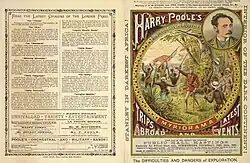

Poole's Myriorama

In the early nineteenth century, British traveling panorama shows had been operated by several firms, among them the Marshall brothers of Glasgow and J.B. Laidlaw. However, it was not until the 1850s that a nearly year-round programme of such shows was offered by Moses Gompertz, who with his assistants the Poole brothers traveled the length and breadth of Britain. Gompertz continued in this line of work through the mid-1880s, when his business was taken over by the Pooles. To distinguish theirs from rival shows, they started to use the name Myriorama which seems to have originated around 1824 with the toy of that name despite suggestions that it was coined by Joseph Poole in about 1883.[6] By 1900 they had seven separate shows touring for 40 weeks of the year.[7] They added elaborate effects to the scrolling paint-and-cloth panoramas: cut-out figures moving across the scene, accompanied by music, lighting and sound effects. The narrator, often one of the Poole brothers in evening dress, would describe and interpret. "Poole's Myriorama" was well-known and is even mentioned in James Joyce's Ulysses.

Stories of travel and adventure, often military adventure, were popular: the action was conveyed by hidden stagehands moving shaped flats across a fixed backdrop. One naval battle had them manoeuvring ships accompanied by gunshot noises, puffs of smoke and Rule Britannia with waves on a rippling cloth at the front of the stage.[8] Some shows, with variety acts as well as myriorama displays, employed dozens of people.

Some of the first films seen in the UK were presented in late 19th century myriorama shows.[9] Although cinema eventually replaced the myriorama, this kind of entertainment stayed popular until the late 1920s, and was considered a Christmas-time treat. In December 1912 the Pooles first presented their Loss of the Titanic in "eight tableaux", starting with "a splendid marine effect" of the ship gliding across the scene.[10] A descendant of theirs, Hudson John Powell, gathered together the family story in Poole's Myriorama!: a story of travelling panorama showmen (2002). The Guardian has called their myrioramas part of the "popular visual culture of the 19th century".[11]

John Reginald Poole (1882 - 1950) was the last of the family in the Myriorama business. His father Charles William Poole had taken over all the family's entertainment concerns. In 1937, he published the book One Hundred Years of Showmanship.[12]

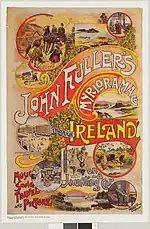

Fuller's Myriorama

A Myriorama company formed in New Zealand in 1896 by John Fuller (1850–1923) used magic lantern images rather than paintings wound on rollers.[13] Their shows offered a changing display of pictures accompanied by commentary and music.

Surviving moving panoramas

Few moving panoramas have survived to this day, and conservation issues prevent them from being shown in their original format. One notable rediscovered moving panorama in the United States is the Grand Moving Panorama of Pilgrim's Progress, which was found in storage at the York Institute, now the Saco Museum, in Saco, Maine by its former curator Tom Hardiman. It was found to incorporate designs by many of the leading painters of its day, including Jasper Francis Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, and Henry Courtney Selous (Selous was the in-house painter for the original Barker panorama in London for many years). Another significant panorama, Russell and Purrington's "Whaling Voyage 'Round the World," is in the collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum and it is currently on exhibit during conservation.[14] C.C.A. Christensen's "Mormon Panorama" survives at Brigham Young University's Museum of Art, where it has been the subject of several recent shows and lectures.

Another moving panorama was donated to the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at the Brown University Library in 2005. Painted in Nottingham, England around 1860 by John James Story (d. 1900), it depicts the life and career of the great Italian patriot, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882). The panorama stands about 4½ feet high and approximately 140 feet (43 m) long, painted on both sides in watercolor. Numerous battles and other dramatic events in his life are depicted in 42 scenes, and the original handwritten narration survives. A section of The Moving Panorama of Texas and California (1851-1852), titled "Independence Hall at Washington-on-the-Brazos" is on display at the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin, Texas. This panorama was commissioned by Levi Sala, and painted by Charles L. Smith. The panorama made its public debut at the Dan Rice Amphitheater on St. Charles Street in New Orleans on May 1, 1852. The scenes were painted by Charles L. Smith from drawings and sketches provided by James G. Benton of sites of historical interest in Texas, including scenes along the Brazos River from San Felipe to Washington-on-the-Brazos, as well as views of the San Antonio Missions and episodes of the Texas Revolution of 1835-1836. Also, a member of the Mier Expedition, Charles McLaughlin, contributed eyewitness sketches of the 1842 Texas incursion into Mexico. An artist known only as Mr. Perrine would supply drawings of the California gold country.[15]

Crankies

Crankies are moving panoramas on a smaller scale, with a typical example being roughly twenty feet long by eighteen inches high. Like the larger moving panorama, a crankie is typically displayed with live music or narration. In the form of crankies, the moving panorama has experienced a revival in the United States since the mid-2010s; one group using them in its performances is the American folk duo Anna & Elizabeth.[16][17]

See also

References

- Travers, Len (1997). Celebrating the Fourth: Independence Day & the Rites of Nationalism in the Early Republic. University of Massachusetts. ISBN 1558492038.

- peristrephic means "panoramic, unfolding" (OED)

- Australian Centre for the Moving Image Archived 2007-09-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "The voters and tax-payers of Bureau county, Illinois". 1877.

- "Krannert Art Museum".

- Huhtamo, Erkki (2013). Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles. p. 292. ISBN 978-0262018517. This says :The word "Myriorama" was introduced around 1883 by Joseph Poole, who defined it: "If we prefix horama with the Greek myriroi, which signifies "various", we arrive at the latest development of this class of entertainment, 'Myriorama' meaning "to view various scenes and objects."

- The Scotsman obituary of Jim Poole, 21 January 1998

- Ralph Lownie, ed. (2004). Auld Reekie: An Edinburgh Anthology. Timewell Press. ISBN 1857252047.

- "Richard Buckley and Heidi Addison, An Historic Building Record of the former Cannon Cinema, Abington Square, Northampton (2001)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-24. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- Bottomore, Stephen (2000). The Titanic and Silent Cinema. The Projection Box. p. 191. ISBN 1903000009.

- The Guardian, 21 January 1998

- Poole, John R. (23 June 2009). "One Hundred Years of Showmanship: Poole's 1837-1937". Bill Douglas collection, Open Research Exeter. hdl:10472/183. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Online Dictionary of NZ Biography". Dnzb.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Museum, New Bedford Whaling. "Purrington-Russell Panorama Conservation Project - New Bedford Whaling Museum". Whalingmuseum.org. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Pinckney, Pauline (1967). Painting in Texas: The Nineteenth Century. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780292736825.

- Colson, Nicole S. (12 January 2018). "Crankie Revival is Nod to Theatrical History". SentinelSource.com. The Keene Sentinel. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Sullivan, Robert (17 March 2018). "What Can an Old Folk Song Tell Us?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

Further reading

- The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium, Stephan Oettermann, (Zone Books, 1997), ISBN 0-942299-83-3

- Banvard's Folly: Thirteen Tales of Renowned Obscurity, Famous Anonymity, and Rotten Luck, by Paul Collins (Picador USA, 2001) ISBN 0-312-26886-6

- Zheng's Route Panorama Digital Route Panorama, IEEE MultiMedia 10(3), 2003

- Mr Clark's myriorama

- Oxford English Dictionary, entry for "peristrephic"

- Making the Scene: A History of Stage Design and Technology in Europe and the United States, Oscar G. Brockett, Margaret Mitchell, and Linda Hardberger. San Antonio, TX: Tobin Theatre Arts Fund, 2010.

- A Trip to Niagara, Or, Travellers in America: A Farce in Three Acts by William Dunlap. New York: E.B. Clayton, 1830.

- Living Theatre: History of Theatre. "Chapter Twelve: Theatres from 1800 to 1875.“ Wilson, Edwin, and Alvin Goldfarb. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012.

External links

- The Moving Panorama, a Forgotten Mass Medium of the 19th Century

- Play the Panorama infinite moving panorama project.

- The Dyer Library and Saco Museum

- Arctic Panoramas of Dr. Elisha Kent Kane

- Moving Panoramas at the Bill Douglas Centre at the University of Exeter.

- Garibaldi & the Risorgimento (Brown University)

- Programme for a myriorama show

- The Poole Brothers

- Meridian Magazine's article on the Mormon Panorama

- Digital Route Panorama

- The Crankie Factory

- "The Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage 'Round the World", New Bedford Whaling Museum