Persian art

Persian art or Iranian art (Persian: هنر ایرانی, romanized: Honar-è Irâni) has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

.jpg.webp)

From the Achaemenid Empire of 550 BC–330 BC for most of the time a large Iranian-speaking state has ruled over areas similar to the modern boundaries of Iran, and often much wider areas, sometimes called Greater Iran, where a process of cultural Persianization left enduring results even when rulership separated. The courts of successive dynasties have generally led the style of Persian art, and court-sponsored art has left many of the most impressive survivals.

In ancient times the surviving monuments of Persian art are notable for a tradition concentrating on the human figure (mostly male, and often royal) and animals. Persian art continued to place larger emphasis on figures than Islamic art from other areas, though for religious reasons now generally avoiding large examples, especially in sculpture. The general Islamic style of dense decoration, geometrically laid out, developed in Persia into a supremely elegant and harmonious style combining motifs derived from plants with Chinese motifs such as the cloud-band, and often animals that are represented at a much smaller scale than the plant elements surrounding them. Under the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century this style was used across a wide variety of media, and diffused from the court artists of the shah, most being mainly painters.

Early arts

.jpg.webp)

Evidence of a painted-pottery civilization around Susa has been dated to c 5000 BCE.[1] Susa was firmly within the Sumerian Uruk cultural sphere during the Uruk period. An imitation of the entire state apparatus of Uruk, proto-writing, cylinder seals with Sumerian motifs, and monumental architecture, is found at Susa. Susa may have been a colony of Uruk. As such, the periodization of Susa corresponds to Uruk; Early, Middle and Late Susa II periods (3800–3100 BCE) correspond to Early, Middle, and Late Uruk periods.

Shortly after Susa was first settled 6000 years ago, its inhabitants erected a temple on a monumental platform that rose over the flat surrounding landscape. The exceptional nature of the site is still recognizable today in the artistry of the ceramic vessels that were placed as offerings in a thousand or more graves near the base of the temple platform. Nearly two thousand pots were recovered from the cemetery most of them now in the Louvre. The vessels found are eloquent testimony to the artistic and technical achievements of their makers, and they hold clues about the organization of the society that commissioned them.[2] Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian Ubaid ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium B.C.[2]

Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery. Others are course cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children.[3] The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

Lullubi rock reliefs

The rock reliefs of the mountain kingdom of Lullubi, especially the Anubanini rock relief, are rock reliefs from circa 2300 BC or the early 2nd millennium BC, the earliest rock reliefs of Iran. They are located in Kermanshah Province.[4][5] These reliefs are thought to have influenced the later Achaemenid Behistun reliefs, about a millennium and a half later.[4][6]

Elam

Elamite art, from the south and west of modern Iran shared many characteristics with the neighbouring art of Mesopotamia, though it was often less sophisticated. Cylinder seals, small figures of worshippers, gods and animals, shallow reliefs, and some large statues of rulers are all found. There are a small number of very fine gold vessels with relief figures.[7]

Luristan bronzes

Luristan bronzes (rarely "Lorestān", "Lorestāni" etc. in sources in English) are small cast objects decorated with bronze sculptures from the Early Iron Age which have been found in large numbers in Lorestān Province and Kermanshah in west-central Iran.[8] They include a great number of ornaments, tools, weapons, horse-fittings and a smaller number of vessels including situlae,[9] and those found in recorded excavations are generally found in burials.[10] The ethnicity of the people who created them remains unclear,[11] though they may well have been Persian, possibly related to the modern Lur people who have given their name to the area. They probably date to between about 1000 and 650 BC.[12]

The bronzes tend to be flat and use openwork, like the related metalwork of Scythian art. They represent the art of a nomadic or transhumant people, for whom all possessions needed to be light and portable, and necessary objects such as weapons, finials (perhaps for tent-poles), horse-harness fittings, pins, cups and small fittings are highly decorated over their small surface area.[13] Representations of animals are common, especially goats or sheep with large horns, and the forms and styles are distinctive and inventive. The "Master of Animals" motif, showing a human positioned between and grasping two confronted animals is common[14] but typically highly stylized.[15] Some female "mistress of animals" are seen.[16]

The Ziwiye hoard of about 700 BC is a collection of objects, mostly in metal, perhaps not all in fact found together, of about the same date, probably showing the art of the Persian cities of the period. Delicate metalwork from Iron Age II times has been found at Hasanlu and still earlier at Marlik.[7]

Achaemenids

Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, metalwork, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening. Most survivals of court art are monumental sculpture, above all the reliefs, double animal-headed Persian column capitals and other sculptures of Persepolis (see below for the few but impressive Achaemenid rock reliefs).[17]

Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they produced not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.[18] Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a specialty of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of earlier sites.

The rhyton drinking vessel, horn-shaped and usually ending in an animal shape, is the most common type of large metalwork to survive, as in a fine example in New York. There are a number of very fine smaller pieces of jewellery or inlay in precious metal, also mostly featuring animals, and the Oxus Treasure has a wide selection of types. Small pieces, typically in gold, were sewn to clothing by the elite, and a number of gold torcs have survived.[17]

Achaemenid griffin capital at Persepolis

Achaemenid griffin capital at Persepolis One of a pair of armlets from the Oxus Treasure, which has lost its inlays of precious stones or enamel

One of a pair of armlets from the Oxus Treasure, which has lost its inlays of precious stones or enamel Similar armlets in the "Apadana" reliefs at Persepolis, also bowls and amphorae with griffin handles are given as tribute

Similar armlets in the "Apadana" reliefs at Persepolis, also bowls and amphorae with griffin handles are given as tribute Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring

Bas-relief in Persepolis—a symbol in Zoroastrian for Nowruz— eternally fighting bull (personifying the moon), and a lion (personifying the Sun) representing the Spring

Rock reliefs

The large carved rock relief, typically placed high beside a road, and near a source of water, is a common medium in Persian art, mostly used to glorify the king and proclaim Persian control over territory.[19] It begins with Lullubi and Elamite rock reliefs, such as those at Sarpol-e Zahab (circa 2000 BC), Kul-e Farah and Eshkaft-e Salman in southwest Iran, and continues under the Assyrians. The Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great, is on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire.[20] Persian rulers commonly boasted of their power and achievements, until the Muslim conquest removed imagery from such monuments; much later there was a small revival under the Qajar dynasty.[21]

Behistun is unusual in having a large and important inscription, which like the Egyptian Rosetta Stone repeats its text in three different languages, here all using cuneiform script: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a later form of Akkadian).[22] This was important in the modern understanding of these languages. Other Persian reliefs generally lack inscriptions, and the kings involved often can only be tentatively identified. The problem is helped in the case of the Sasanians by their custom of showing a different style of crown for each king, which can be identified from their coins.[21]

Naqsh-e Rustam is the necropolis of the Achaemenid dynasty (500–330 BC), with four large tombs cut high into the cliff face. These have mainly architectural decoration, but the facades include large panels over the doorways, each very similar in content, with figures of the king being invested by a god, above a zone with rows of smaller figures bearing tribute, with soldiers and officials. The three classes of figures are sharply differentiated in size. The entrance to each tomb is at the centre of each cross, which opens onto a small chamber, where the king lay in a sarcophagus.[23] The horizontal beam of each of the tomb's facades is believed to be a replica of the entrance of the palace at Persepolis.

Only one has inscriptions and the matching of the other kings to tombs is somewhat speculative; the relief figures are not intended as individualized portraits. The third from the left, identified by an inscription, is the tomb of Darius I the Great (c. 522–486 BC). The other three are believed to be those of Xerxes I (c. 486–465 BC), Artaxerxes I (c. 465–424 BC), and Darius II (c. 423–404 BC) respectively. A fifth unfinished one might be that of Artaxerxes III, who reigned at the longest two years, but is more likely that of Darius III (c. 336–330 BC), last of the Achaemenid dynasts. The tombs were looted following the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great. [23]

Well below the Achaemenid tombs, near ground level, are rock reliefs with large figures of Sassanian kings, some meeting gods, others in combat. The most famous shows the Sassanian king Shapur I on horseback, with the Roman Emperor Valerian bowing to him in submission, and Philip the Arab (an earlier emperor who paid Shapur tribute) holding Shapur's horse, while the dead Emperor Gordian III, killed in battle, lies beneath it (other identifications have been suggested). This commemorates the Battle of Edessa in 260 AD, when Valerian became the only Roman Emperor who was captured as a prisoner of war, a lasting humiliation for the Romans. The placing of these reliefs clearly suggests the Sasanian intention to link themselves with the glories of the earlier Achaemenid Empire.[24] There are three further Achaemenid royal tombs with similar reliefs at Persepolis, one unfinished.[25]

The seven Sassanian reliefs, whose approximate dates range from 225 to 310 AD, show subjects including investiture scenes and battles. The earliest relief at the site is Elamite, from about 1000 BC. About a kilometre away is Naqsh-e Rajab, with a further four Sasanian rock reliefs, three celebrating kings and one a high priest. Another important Sasanian site is Taq Bostan with several reliefs including two royal investitures and a famous figure of a cataphract or Persian heavy cavalryman, about twice life size, probably representing the king Khosrow Parviz mounted on his favourite horse Shabdiz; the pair continued to be celebrated in later Persian literature.[26] Firuzabad, Fars and Bishapur have groups of Sassanian reliefs, the former including the oldest, a large battle scene, now badly worn.[27] At Barm-e Delak a king offers a flower to his queen.

Sassanian reliefs are concentrated in the first 80 years of the dynasty, though one important set are 6th-century, and at relatively few sites, mostly in the Sasanian heartland. The later ones in particular suggest that they draw on a now-lost tradition of similar reliefs in palaces in stucco. The rock reliefs were probably coated in plaster and painted.[21]

The rock reliefs of the preceding Persian Selucids and Parthians are generally smaller and more crude, and not all direct royal commissions as the Sasanian ones clearly were.[28] At Behistun an earlier relief including a lion was adapted into a reclining Herakles in a fully Hellenistic style; he reclines on a lion skin. This was only uncovered below rubble relatively recently; an inscription dates it to 148 BC.[29] Other reliefs in Iran include the Assyrian king in shallow relief at Shikaft-e Gulgul; not all sites with Persian reliefs are in modern Iran.[21] Like other Sassanian styles, the form enjoyed a small revival under the Qajar, whose reliefs include a large and lively panel showing hunting at the royal hunting-ground of Tangeh Savashi, and a panel, still largely with its colouring intact, at Taq Bostan showing the shah seated with attendants.

The standard catalogue of pre-Islamic Persian reliefs lists the known examples (as at 1984) as follows: Lullubi #1–4; Elam #5–19; Assyrian #20–21; Achaemenid #22–30; Late/Post-Achaemenid and Seleucid #31–35; Parthian #36–49; Sasanian #50–84; others #85–88.[30]

Parthians

.jpg.webp)

The art of the Parthians was a mix of Iranian and Hellenistic styles. The Parthian Empire existed from 247 BC to 224 AD in what is now Greater Iran and several territories outside it. Parthian places are often overlooked in excavations, and Parthian layers difficult to distinguish from those around them.[31] The research situation and the state of knowledge on Parthian art is therefore still very patchy; dating is difficult and the most important remains come from the fringes of the empire, as at Hatra in modern Iraq, which has produced the largest quantity of Parthian sculpture yet excavated.[32] Even after the period of the Parthian dynasty, art in its style continued in surrounding areas for some time. Even in narrative representations, figures look frontally out to the viewer rather than at each other, a feature that anticipates the art of Late Antiquity, medieval Europe and Byzantium. Great attention is paid to the details of clothing, which in full-length figures is shown decorated with elaborate designs, probably embroidered, including large figures.[33]

The excavations at Dura-Europos in the 20th century provided many new discoveries. The classical archaeologist and director of the excavations, Michael Rostovtzeff, realized that the art of the first centuries AD, Palmyra, Dura Europos, but also in Iran up to the Buddhist India followed the same principles. He called this artwork Parthian art.[34]

The most characteristic feature of the "Parthian" art is frontality which is not a special feature of Iranic or Parthian art and first appeared in the art of Palmyra.[35] There are doubts whether this art can be called a "Parthian" art or that it should be associated with any particular regional area; there is no evidence that this art was created outside the middle-Euphrates region then brought to Palmyra for example.[36] This art is better thought of as a local development common to the middle Euphrates region.[36] Parthian rock reliefs are covered above.

In architecture, patterns in plaster were very popular, almost all now lost. Once the technique was developed these covered large surfaces and perhaps shared elements of their design with carpets and other textiles, also now almost entirely lost.[37] Parthian rhyta continued the Achaemenid style, but in the best the animals at the terminal (or protome) are more naturalistic, probably under Greek influence.

Sasanians

Sasanian art, or Sasanian art, was produced under the Sasanian Empire which ruled from the 3rd to 7th centuries AD, before the Muslim conquest of Persia was completed around 651. In 224 AD, the last Parthian king was defeated by Ardashir I. The resulting Sasanian dynasty would last for four hundred years, ruling modern Iran, Iraq, and much territory to the east and north of modern Iran. At times the Levant, much of Anatolia and parts of Egypt and Arabia were under its control. It began a new era in Iran and Mesopotamia, which in many ways was built on Achaemenid traditions, including the art of the period. Nevertheless, there were also other influences on art of the period that came from as far as China and the Mediterranean.[38]

The surviving art of the Sasanians is best seen in its architecture, reliefs and metalwork, and there are some surviving paintings from what was evidently a widespread production. Stone reliefs were probably greatly outnumbered by interior ones in plaster, of which only fragments have survived. Free standing sculptures faded out of popularity in this time as compared to the period under the Parthians, but the Colossal Statue of Shapur I (r. AD 240–272) is a major exception, carved from a stalagmite grown in a cave;[39] there are literary mentions of other colossal statues of kings, now lost.[40] The important Sasanian rock reliefs are covered above, and the Parthian tradition of moulded stucco decoration to buildings continued, also including large figurative scenes.[39]

Surviving Sasanian art depicts courtly and chivalric scenes, with considerable grandeur of style, reflecting the lavish life and display of the Sasanian court as recorded by Byzantine ambassadors. Images of rulers dominate many of the surviving works, though none are as large as the Colossal Statue of Shapur I. Hunting and battle scenes enjoyed a special popularity, and lightly-clothed dancing girls and entertainers. Representations are often arranged like a coat of arms, which in turn may have had a strong influence on the production of art in Europe and East Asia. Although Parthian art preferred the front view, the narrative representations of the Sassanian art often features figures shown in the profile or a three-quarter view. Frontal views occur less frequently.[39]

One of the few sites where wall-paintings survived in quantity is Panjakent in modern Tajikistan, and ancient Sogdia, which was barely, if at all, under the control of the central Sasanian power. The old city was abandoned in the decades after the Muslims eventually took the city in 722 and has been extensively excavated in modern times. Large areas of wall paintings survived from the palace and private houses, which are mostly now in the Hermitage Museum or Tashkent. They covered whole rooms and were accompanied by large quantities of reliefs in wood. The subjects are similar to other Sasanian art, with enthroned kings, feasts, battles, and beautiful women, and there are illustrations of both Persian and Indian epics, as well as a complex mixture of deities. They mostly date from the 7th and 8th centuries.[41] At Bishapur floor mosaics in a broadly Greco-Roman style have survived, and these were probably widespread in other elite settings, perhaps made by craftsmen from the Greek world.[42]

A number of Sasanid silver vessels have survived, especially rather large plates or bowls used to serve food. These have high-quality engraved or embossed decoration from a courtly repertoire of mounted kings or heroes, and scenes of hunting, combat and feasting, often partially gilded. Ewers, presumably for wine, may feature dancing girls in relief. These were exported to China, and also westwards.[43]

Sasanian glass continued and developed Roman glass technology. In simpler forms it seems to have been available to a wide range of the population, and was a popular luxury export to Byzantium and China, even appearing in elite burials from the period in Japan. Technically, it is a silica-soda-lime glass production characterized by thick glass-blown vessels relatively sober in decoration, avoiding plain colours in favour of transparency and with vessels worked in one piece without over-elaborate amendments. Thus the decoration usually consists of solid and visual motifs from the mould (reliefs), with ribbed and deeply cut facets, although other techniques like trailing and applied motifs were practised.[39] Sasanian pottery does not seem to have been used by the elites, and is mostly utilitarian.

Carpets evidently could reach a high level of sophistication, as the praise lavished on the lost royal Baharestan Carpet by the Muslim conquerors shows. But the only surviving fragments that might originate from Sasanid Persia are humbler productions, probably made by nomad tribes. Sasanid textiles were famous, and fragments have survived, mostly with designs based on animals in compartments, in a long-lasting style.[39]

%252C_pendjikent%252C_sett._VI%252C_cam._41%252C_angolo_n.o.%252C_740_ca._2.JPG.webp) Sections of wall-paintings from Panjakent, c. 740

Sections of wall-paintings from Panjakent, c. 740

The so-called "Coupe de Chosroès", metal and carved semi-precious stone

The so-called "Coupe de Chosroès", metal and carved semi-precious stone Silver-gilt head of a king, 4th century

Silver-gilt head of a king, 4th century Vases with dancing beauties, c. 300–500

Vases with dancing beauties, c. 300–500 Rhyton with female head and water buffalo, c. 600–700, silver

Rhyton with female head and water buffalo, c. 600–700, silver Silver partly gilded dish with the favourite subject of the king hunting, 7th century

Silver partly gilded dish with the favourite subject of the king hunting, 7th century

Sogdians

Sogdian art refers to the art, architecture, and art-forms produced by the Sogdians, an Iranian people who lived mostly in Sogdia in Central Asia, but also had a large diaspora spread throughout Asia, especially in China, where their art was much appreciated, and influenced the Chinese. This influence on the Chinese ranged from metallurgy to music. Today, the Sogdians are best known for their paintings, but they had a distinctive sculpture and architecture as well.

The Sogdians were especially talented in metalworking, and their work in this field inspired the Chinese, who were among their patrons together with the Turks. The Sogdian metalwork may be confused with Sasanian metalwork, and the two are still confused by some scholars today. However, they differentiate in technique and shape, as well as iconography. Thanks to the work of archaeologist Boris Marshak, several characteristic of Sogdian metalwork have been established: with respect to Sasanian vessels, Sogdian productions are less massive, their shape differs from the Sasanian, as do the techniques employed in their production. Further, the designs of Sogdian productions are more dynamic.[44][45]

The Sogdians lived in architecturally complex abodes that resembled their temples. These places were decorated with remarkable paintings, an art in which the Sogdians excelled. Indeed, they preferred to produce paintings and wood carvings to decorate their own houses. Sogdian wall paintings are bright, vigorous, and of remarkable beauty, but also tell about Sogdian life. They reproduce, for example, the costumes of the day, the gaming equipment, and the harness. They also depict stories and epics drawing on Iranian, Near Eastern (Manichaean, Nestorian) and Indian themes. Sogdian religious art reflects the religious affiliations of the Sogdians, and this knowledge is derived mostly from paintings and ossuaries.[46] Through these artifacts, it is possible to "experience the vibrancy of Sogdian life and imagination."[46]

Because Sogdian artists, and patrons, were much attentive to social life, displaying it in their works, banqueting, hunting, and entertainment are recurrent in their representations. The Sogdians were storytellers: they loved to recount stories. Thus, their paintings are narrative in nature.[47]

The Sogdians sought to portray both the supernatural and natural worlds. This desire "extended into portraying their own world." However, they did not "represent their mercantile activities, a major source of their wealth, but instead chose to show their enjoyment of it, such as the scenes of banqueting at Panjikent. In these paintings we see how the Sogdians saw themselves."[47]

Many Sogdian paintings were destroyed during the several invasions they suffered in their land. Of the works which survived, some of the best known are the Afrasiab murals and the Penjikent murals.

Detail from Penjikent murals, 5th–8th century

Detail from Penjikent murals, 5th–8th century Sogdian banquet, Penjikent murals, 5th–8th century

Sogdian banquet, Penjikent murals, 5th–8th century_mural_%252C_6th-8th_Centuries_(2).jpg.webp) Detail of the Penjikent murals

Detail of the Penjikent murals

Early Islamic period

Before the Mongol conquest

Persia managed to retain its cultural identity after the Muslim conquest of Persia, which was complete by 654, and the Arab conquerors soon gave up attempts to impose the Arabic language on the population, although it became the language used by scholars. Turkic peoples became increasingly important in Greater Iran, especially the eastern parts, leading to a cultural Turko-Persian tradition. The political structure was complex, with effective power often exercised by local rulers.[48]

Nishapur during the Islamic Golden Age, especially the 9th and 10th centuries, was one of the great centres of pottery and related arts.[49] Most of the ceramic artefacts discovered in Nishapur are preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and museums in Tehran and Mashhad. Ceramics produced at Nishapur showed links with Sasanian art and Central Asian art.[50]

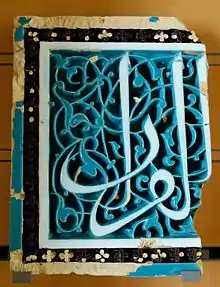

Geometric Islamic architectural decoration in stucco, tiling, brick and carved wood and stone became elaborate and refined, and along with textiles worn by the rich was probably the main type of art that could be seen by the whole population, with other types essentially restricted to the private spheres of the rich.[51] Carpets are recorded in several accounts of life at the time, but none remain; they were perhaps mainly a rural folk art at this period. Very highly decorated metalwork in copper alloys (brass or bronze) was produced, apparently for a sophisticated urban market. Gold and silver equivalents apparently existed but have been mostly recycled for their precious materials; the few survivals were mostly traded north for furs and then buried as grave goods in Siberia. Sasanid iconography of mounted heroes, hunting scenes, and seated rulers with attendants remained popular in pottery and metalwork, now often surrounded by elaborate geometrical and calligraphic decoration.[52] The rich silk textiles that were an important export from Persia also continued to use the animal, and sometimes human, figures of their Sasanid predecessors.[53]

The Samanid period saw the creation of epigraphic pottery. These pieces were typically earthenware vessels with black slip lettering in Kufi script painted on a base of white slip. These vessels would typically be inscribed with blessings or proverbs, and used to serve food.[54] Samarqand and Nishapur were both centres of production for this kind of pottery.[55]

The Seljuqs, nomads of Turkic origin from present-day Mongolia, appeared on the stage of Islamic history toward the end of the 10th century. They seized Baghdad in 1048, before dying out in 1194 in Iran, although the production of "Seljuq" works continued through the end of the 12th and beginning of the 13th century under the auspices of smaller, independent sovereigns and patrons. During their time, the center of culture, politics and art production shifted from Damascus and Baghdad to Merv, Nishapur, Rayy, and Isfahan, all in Iran.[56] Seljuq palace centres often featured Seljuk stucco figures.

Popular patronage expanded because of a growing economy and new urban wealth. Inscriptions in architecture tended to focus more on the patrons of the piece. For example, sultans, viziers or lower ranking officials would receive often mention in inscriptions on mosques. Meanwhile, growth in mass market production and sale of art made it more commonplace and accessible to merchants and professionals.[57] Because of increased production, many relics have survived from the Seljuk era and can be easily dated. In contrast, the dating of earlier works is more ambiguous. It is, therefore, easy to mistake Seljuk art as new developments rather than inheritance from classical Iranian and Turkic sources.[58]

Innovations in ceramics from this period include the production of mina'i ware, painted in enamels with figures on a white background. This is the earliest pottery anywhere to use overglaze enamel painting, which only began in China slightly later, and in Europe in the 18th century. This and other types of fine pottery use fritware, a silicon-based paste, rather than clay.[59] Metalworkers highlighted their intricate hammered designs with precious metal inlays.[60] Across the Seljuk era, from Iran to Iraq, a unification of book painting can be seen. These paintings have animalistic figures that convey strong symbolic meaning of fidelity, treachery, and courage.[61]

The Persians gradually adopted Arabic scripts after the conquest, and Persian calligraphy became an important artistic medium, often used as part of the decoration of other works in most media.[62]

Ilkhanids

During the 13th century, the Mongols under the leadership of Genghis Khan swept through the Islamic world. After his death, his empire was divided among his sons, forming many dynasties: the Yuan in China, the Ilkhanids in Iran and the Golden Horde in northern Iran and southern Russia, the latter two converting to Islam within a few decades.[63]

A rich civilization developed under these "little khans," who were originally subservient to the Yuan emperor, but rapidly became independent. Architectural activity intensified as the Mongols became sedentary, and retained traces of their nomadic origins, such as the north-south orientation of the buildings. At the same time a process of "iranisation" took place, and construction according to previously established types, such as the "Iranian plan" mosques, was resumed. The art of the Persian book was also born under this dynasty, and was encouraged by aristocratic patronage of large manuscripts such as the Jami' al-tawarikh compiled by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, and the Demotte or Great Mongol Shahnameh, probably commissioned by his son. New techniques in ceramics appeared, such as the lajvardina (a variation on lusterware), and Chinese influence is perceptible in all arts.[64][65]

Timurids

During the reign of the Timurids, the golden age of Persian painting began, and Chinese influence continued, as Timurid artists refined the Persian art of the book, which combines paper, calligraphy, illumination, illustration and binding in a brilliant and colourful whole.[66] From the start paper was used, rather than parchment as in Europe. It was the Mongol ethnicity of the Chaghatayid and Timurid Khans that is the source of the stylistic depiction of the human figure in Persian art during the Middle Ages. These same Mongols intermarried with the Persians and Turks of Central Asia, even adopting their religion and languages. Yet their simple control of the world at that time, particularly in the 13–15th centuries, reflected itself in the idealised appearance of Persians as Mongols. Though the ethnic make-up gradually blended into the Iranian and Mesopotamian local populations, the Mongol stylism continued well after, and crossed into Asia Minor and even North Africa.[67]

Luster-ware bowl from Susa, 9th century

Luster-ware bowl from Susa, 9th century Perfume-burner, 11th century, Khorasan or Central Asia

Perfume-burner, 11th century, Khorasan or Central Asia Bowl with a hunting scene from the tale of the 5th-century king Bahram Gur and Azadeh, mina'i ware.

Bowl with a hunting scene from the tale of the 5th-century king Bahram Gur and Azadeh, mina'i ware. Jug, 15th century, gilt-bronze with silver inlay, probably styled for the European market

Jug, 15th century, gilt-bronze with silver inlay, probably styled for the European market

Carpets

Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and art. Within the group of Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the so-called "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its designs.[68]

Persian carpets and rugs of various types were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes, in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories alike. As such, they represent different, simultaneous lines of tradition, and reflect the history of Iran and its various peoples. The carpets woven in the Safavid court manufactories of Isfahan during the sixteenth century are famous for their elaborate colours and artistical design, and are treasured in museums and private collections all over the world today. Their patterns and designs have set an artistic tradition for court manufactories which was kept alive during the entire duration of the Persian Empire up to the last royal dynasty of Iran. Exceptional individual Safavid carpets include the Ardabil Carpet (now in London and Los Angeles) and the Coronation Carpet (now in Copenhagen). Much earlier, the Baharestan Carpet is a lost Sasanian carpet for the royal palace at Ctesiphon, and the oldest significant carpet, the Pazyryk Carpet was possibly made in Persia.[68]

Carpets woven in towns and regional centres like Tabriz, Kerman, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns. Town manufactories like those of Tabriz have played an important historical role in reviving the tradition of carpet weaving after periods of decline. Rugs woven by the villages and various tribes of Iran are distinguished by their fine wool, bright and elaborate colours, and specific, traditional patterns. Nomadic and small village weavers often produce rugs with bolder and sometimes more coarse designs, which are considered as the most authentic and traditional rugs of Persia, as opposed to the artistic, pre-planned designs of the larger workplaces. Gabbeh rugs are the best-known type of carpet from this line of tradition.[68]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

The art and craft of carpet weaving has gone through periods of decline during times of political unrest, or under the influence of commercial demands. It particularly suffered from the introduction of synthetic dyes during the second half of the nineteenth century. Carpet weaving still plays a major part in the economy of modern Iran.[68] Modern production is characterized by the revival of traditional dyeing with natural dyes, the reintroduction of traditional tribal patterns, but also by the invention of modern and innovative designs, woven in the centuries-old technique. Hand-woven Persian carpets and rugs were regarded as objects of high artistic and utilitarian value and prestige from the first time they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers, until today.

Although the term "Persian carpet" most often refers to pile-woven textiles, flat-woven carpets and rugs like Kilim, Soumak, and embroidered fabrics like Suzani are part of the rich and manifold tradition of Persian weaving. Persia was famous for its textiles at least as early as for its carpets.[68]

In 2010, the "traditional skills of carpet weaving" in Fārs and Kashan were inscribed to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[69][70]

Persian miniature

A Persian miniature is a small painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an older Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant Persian genre in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests,[71] and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries.[72] The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this,[73] and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

The tradition grew from book illustration, illustrating many narrative scenes, often with many figures. The representational conventions that developed are effective but different from Western graphical perspective. More important figures may be somewhat larger than those around them, and battle scenes can be very crowded indeed. Recession (depth in the picture space) is indicated by placing more distant figures higher up in the space. Great attention is paid to the background, whether of a landscape or buildings, and the detail and freshness with which plants and animals, the fabrics of tents, hangings or carpets, or tile patterns are shown is one of the great attractions of the form. The dress of figures is equally shown with great care, although artists understandably often avoid depicting the patterned cloth that many would have worn. Animals, especially the horses that very often appear, are mostly shown sideways on; even the love-stories that constitute much of the classic material illustrated are conducted largely in the saddle, as far as the prince-protagonist is concerned. Landscapes are very often mountainous (the plains that make up much of Persia are rarely attempted), this being indicated by a high undulating horizon, and outcrops of bare rock which, like the clouds in the normally small area of sky left above the landscape, are depicted in conventions derived from Chinese art. Even when a scene in a palace is shown, the viewpoint often appears to be from a point some metres in the air.[74]

Persian art under Islam had never completely forbidden the human figure, and in the miniature tradition the depiction of figures, often in large numbers, is central. This was partly because the miniature is a private form, kept in a book or album and only shown to those the owner chooses. It was therefore possible to be more free than in wall paintings or other works seen by a wider audience. The Qur'an and other purely religious works are not known to have been illustrated in this way, though histories and other works of literature may include religiously related scenes, including those depicting Muhammed, after 1500 usually without showing his face.[75]

As well as the figurative scenes in miniatures and borders, there was a parallel style of non-figurative ornamental decoration which was found in borders and panels in miniature pages, and spaces at the start or end of a work or section, and often in whole pages acting as frontispieces. In Islamic art this is referred to as "illumination", and manuscripts of the Qur'an and other religious books often included considerable number of illuminated pages.[76] The designs reflected contemporary work in other media, in later periods being especially close to book-covers and Persian carpets, and it is thought that many carpet designs were created by court artists and sent to the workshops in the provinces.[77]

Safavids

Safavid art is the art of the Persian Safavid dynasty from 1501 to 1722. It was a high point for the art of the book and architecture; and also including ceramics, metal, glass, and gardens. The arts of the Safavid period show a far more unitary development than in any other period of Persian art,[78] with the same style, diffused from the court, appearing in carpets, architectural tiles, ceramics, and manuscript illumination.[79]

When the Safavids seized the throne Persian art had become divided into two styles: in the east a continuation of Timurid styles, and in the west a Turkman style. Two rulers of the new dynasty succeeded in encouraging new styles that spread all over their territories: Shah Tahmasp I, who reigned 1524–1576 but lost interest in art after about 1555, and Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629).[80]

Chinese imitation drawings emerged in 15th century Persian art. Scholars have noted that extant works from the post-Mongol period contain an abundance of motifs common to Chinese art like dragons, simurgh, cloud-bands, gnarled tree trunks, and lotus and peony flowers. Chinoiserie was popular during this period. Themes that had become standard in Persian art by the 16th and 17th centuries included hunting scenes, landscapes featuring animals and horsemen battling lions. Literary scenes depicting animal fables and dragons also featured in the artwork of this period. Scholars have not found evidence of Persian drawing before the Mongol invasions but hunting, combat between men and animals and animal fables are believed to be Persian or Central Asian themes.[81]

Arts of the book

Under the Safavids, the art of the book, especially Persian miniature painting, constituted the essential driving force of the arts. The ketab khaneh, the royal library-workshop, provided most of the sources of motifs for objects such as carpets, ceramics or metal. Various types of books were copied, illuminated, bound and sometimes illustrated: religious books – Korans, but also commentaries on the sacred text and theological works—and books of Persian literature – the Shahnameh, Nizami's Khamsa, Jami al-Tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, and shorter accounts of the Mi'raj, or "Night Journey" of the Prophet.[82]

Muslim Spanish paper arriving early in Iran (13th century), was always used. There is frequent use of coloured papers. Towards 1540, a marbled paper also appeared, which however rapidly disappeared again. The bindings were mostly in tinted Morocco leather of very fine quality. They could be gilded and stamped with geometric, floral or figurative motifs, or embossed in blue. In the second half of the 16th century, they pierced the leather covers to allow the coloured paper or silk pages to be seen. In the same period, at Shiraz, appeared lacquered bindings, which remain however very rare and highly valued in Iran. The decoration of page margins was realised in various ways: sometimes they were inserted in a different paper, (a tradition that appeared in the 15th century); sprinkled with gold, following a Chinese custom; or painted with colours or gold. The style of illustrations varied greatly from one manuscript to another, according to the period and centre of production.[83]

Tahmasp I was for the early years of his reign a generous funder of the royal workshop, who were responsible for several of the most magnificent Persian manuscripts, but from the 1540s he was increasingly troubled by religious scruples, until in 1556 he finally issued an "Edict of Sincere Repentance" attempting to outlaw miniature painting, music and other arts.[84] This greatly disrupted the arts, with many painters such as Abd al-Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali moving to India to develop the Mughal miniature instead; these two were the trail-blazers, headhunted by the Mughal Emperor Humayun when he was in exile in 1546. Others found work at the provincial courts of Tahmasp's relations.[85]

From this dispersal of the royal workshop there was a shift in emphasis from large illustrated books for the court to the production of single sheets designed to be put into a muraqqa, or album. These allowed collectors with more modest budgets to acquire works by leading painters. By the end of the century complicated narrative scenes with many figures were less popular, replaced by sheets with single figures, often only partially painted and with a garden background drawn rather than painted. The master of this style was Reza Abbasi whose career largely coincided with the reign of Abbas I, his main employer. Although he painted figures of old men, his most common subjects were beautiful young men and (less often) women or pairs of lovers.[86]

Rustam sleeps, while his horse Rakhsh fends off a tiger. Probably an early work by Sultan Mohammed, 1515–20

Rustam sleeps, while his horse Rakhsh fends off a tiger. Probably an early work by Sultan Mohammed, 1515–20

Khusraw discovers Shirin bathing in a pool, a favourite scene, here from 1548. The silver used to paint the stream has oxidized to black.

Khusraw discovers Shirin bathing in a pool, a favourite scene, here from 1548. The silver used to paint the stream has oxidized to black. Youth kneeling and holding out a wine-cup, a typical miniature intended for an album by Riza Abbasi

Youth kneeling and holding out a wine-cup, a typical miniature intended for an album by Riza Abbasi

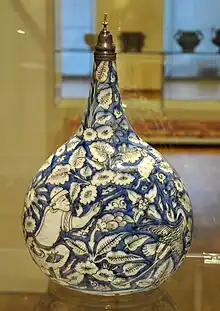

Ceramics

The study and dating of ceramics under Shah Ismail and Shah Tahmasp is difficult because there are few pieces which are dated or which mention the place of production. Chinese porcelain was collected by the elite and more highly valued than the local productions; Shah Abbas I donated much of the royal collection to the shrines at Ardabil and Mashad, renovating a room at Ardabil to display pieces in niches.[88] Many locations of workshops have been identified, although not with certainty, in particular: Nishapur, Kubachi ware, Kerman (moulded monochromatic pieces) and Mashhad. Lusterware was revived, using a different technique from the earlier production, and typically producing small pieces with a design in a dark copper colour over a dark blue background. Unlike other wares, these use traditional Middle Eastern shapes and decoration rather than Chinese-inspired ones.[79]

In general, the designs tend to imitate those of Chinese porcelain, with the production of blue and white pieces with Chinese form and motifs, with motifs such as chi clouds, and dragons.[79] The Persian blue is distinguished from the Chinese blue by its more numerous and subtle nuances. Often, quatrains by Persian poets, sometimes related to the destination of the piece (allusion to wine for a goblet, for example) occur in the scroll patterns. A completely different type of design, much more rare, carries iconography very specific to Islam (Islamic zodiac, bud scales, arabesques) and seems influenced by the Ottoman world, as is evidenced by feather-edged anthemions (honeysuckle ornaments) widely used in Turkey. New styles of figures appeared, influenced by the art of the book: young, elegant cupbearers, young women with curved silhouettes, or yet cypress trees entangling their branches, reminiscent of the paintings of Reza Abbasi.

Numerous types of pieces were produced: goblets, plates, long-necked bottles, spitoons, etc. A common shape is flasks with very small necks and bodies flattened on one side and very rounded on the other. Shapes borrowed from Islamic metalwork with decoration largely inspired by Chinese porcelain are characteristic.[89] With the closing of the Chinese market in 1659, Persian ceramic soared to new heights, to fulfill European needs. The appearance of false marks of Chinese workshops on the backs of some ceramics marked the taste that developed in Europe for far-eastern porcelain, satisfied in large part by Safavid production. This new destination led to wider use of Chinese and exotic iconography (elephants) and the introduction of new forms, sometimes astonishing (hookahs, octagonal plates, animal-shaped objects).

Plate, 16th century, imitating Chinese Kraak ware

Plate, 16th century, imitating Chinese Kraak ware Plate, Kubachi ware, 16th century

Plate, Kubachi ware, 16th century Tile with young man. Earthenware, painted on slip and under transparent glaze. Northwestern Iran, Kubachi ware, 17th century

Tile with young man. Earthenware, painted on slip and under transparent glaze. Northwestern Iran, Kubachi ware, 17th century Lustreware wine bottle, 2nd half 17th century

Lustreware wine bottle, 2nd half 17th century

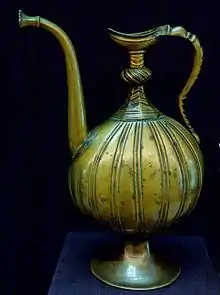

Metalwork

Metalwork saw a gradual decline during the Safavid dynasty, and remains difficult to study, particularly because of the small number of dated pieces. Under Shah Ismail, there is a perpetuation of the shapes and decorations of Timurid inlays: motifs of almond-shaped glories, of shamsa (suns) and of chi clouds are found on the inkwells in the form of mausoleums or the globular pitchers reminiscent of Ulugh Beg's jade one. Under Shah Tahmasp, inlays disappeared rapidly, as witnessed by a group of candlesticks in the form of pillars.[90]

Coloured paste (red, black, green) inlays begin to replace the previous inlays of silver and gold. Openwork panels in steel appear, for uses such as elements of doors, plaques with inscriptions, and the heads of 'alams, the standards carried in Shi'ite religious processions.[91] Important shrines were given doors and jali grilles in silver and even gold.[92]

Hardstone carvings

Persian hardstone carvings, once thought to mostly date to the 15th and 16th centuries, are now thought to stretch over a wider period. Jade was increasingly appreciated from the Ilkhanid period. As well as wine-cups,[93] there are a series of pitchers with globular bellies, mounted on a little ring-shaped base and having wide, short necks. Two of these (one in black jade inlaid with gold, the other in white jade) are inscribed with the name of Ismail I. The handle is in the shape of a dragon, which betrays a Chinese influence, but this type of pitcher comes in fact directly from the preceding period: its prototype is the pitcher of Ulugh Beg. We also know of blades and handles of knives in jade, often inlaid with gold wire and engraved. Hardstone serves also to make jewels to inlay in metal objects, such as the great zinc bottle inlaid with gold, rubies and turquoise dated to the reign of Ismail and conserved at the museum of Topkapi in Istanbul.

Qajars

Qajar art refers to the art, architecture, and art-forms of the Qajar dynasty of the late Persian Empire, which lasted from 1781 to 1925. The boom in artistic expression that occurred during the Qajar era was the fortunate side effect of the period of relative peace that accompanied the rule of Agha Muhammad Khan and his descendants. With his ascension, the bloody turmoil that had been the eighteenth century in Persia came to a close, and made it possible for the peacetime arts to again flourish. European influence was strong, and produced new genres like painted enamel decoration on metal, typically with flowers that clearly draw on French and other European styles. Lacquer on wood is used in a similar way.[94]

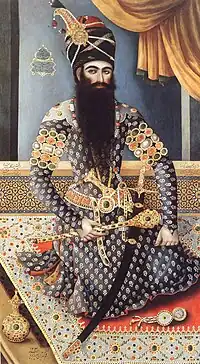

Qajar painting

Painting now adopted the European technique of oil painting. Large murals of scenes of revelry, and historical scenes, were produced as murals for palaces and coffee houses, and many portraits have an arched top showing they were intended to be inset into walls. Qajar art has a distinctive style of portraiture. The roots of traditional Qajar painting can be found in the style of painting that arose during the preceding Safavid empire. During this time, there was a great deal of European influence on Persian culture, especially in the arts of the royalty and noble classes. Though some modelling is used, heavy application of paint and large areas of flat, dark, rich, saturated colours predominate.[95]

While the depiction of inanimate objects and still lifes is seen to be very realistic in Qajar painting, the depiction of human beings is decidedly idealised. This is especially evident in the portrayal of Qajar royalty, where the subjects of the paintings are very formulaically placed with standardised features. However, the impact of photography greatly increased the individuality of portraits in the later 19th century.[96]

Kamal-ol-molk (1845–1940) came from a family of court painters, but also trained with a painter who had studied in Europe. After a career at court, he visited Europe in 1898, at the age of 47, staying for some four years. He was one of the artists who introduced a more European style to Persian painting.[97]

Royal portraiture

Most famous of the Qajar artworks are the portraits that were made of the various Persian Shahs. Each ruler, and many of their sons and other relatives, commissioned official portraits of themselves either for private use or public display. The most famous of these are the myriad portraits which were painted of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, who, with his narrow waist, long black bifurcated beard and deepest eyes, has come to exemplify the Romantic image of the great Oriental Ruler. Many of these paintings were by the artist Mihr 'Ali. While the portraits were executed at various points throughout the life of the Shah, they adhere to a canon in which the distinctive features of the ruler are emphasized.[98]

There are portraits of Fath Ali Shah in a very wide assortment of settings, from the armour-clad warrior king to the flower-smelling gentleman, but all are similar in their depiction of the Shah, differing only slightly, usually due to the specific artist of the portrait. It is only appropriate that this particular Shah be so immortalized in this style, as it was under his rule as the second Qajar shah that the style truly flourished. One reason for this were the stronger and stronger diplomatic ties that the Qajar rulers were nurturing with European powers.[99]

Notes

- Langer, William L., ed. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3.

- Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 26.

- Aruz, Joan (1992). The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: Abrams. p. 29.

- Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 318. ISBN 9780521564960.

- Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781438453255. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Wiesehofer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia. I.B.Tauris. p. 13. ISBN 9781860646751.

- Porada

- "Luristan" remains the usual spelling in art history for the bronzes, as for example in EI, Muscarella, Frankfort, and current museum practice

- Muscarella, 112–113

- Muscarella, 115–116; EI I

- Muscarella, 116–117; EI I

- EI, I

- Frankfort, 343-48; Muscarella, 117 is less confident that they were not settled.

- EI I

- Frankfort, 344-45

- Muscarella, 125–126

- Cotterell, 161–162

- Edward Lipiński, Karel van Lerberghe, Antoon Schoors; Karel Van Lerberghe; Antoon Schoors (1995). Immigration and emigration within the ancient Near East. Peeters Publishers. p. 119. ISBN 978-90-6831-727-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Cotterell, 162 - Canepa, 53 and throughout. Canepa, 63–64, 76–78 on siting

- Luschey; Canepa, 55–57

- Herrmann and Curtis

- Luschey

- Cotterell, 162; Canepa, 57–59, 65–68

- Herrmann and Curtis; Canepa, 62, 65–68

- "Vanden Berghe #27–29". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- Herrmann and Curtis; Canepa, 74–76

- Herrmann and Curtis; Keall for the six at Bishapur

- Canepa, 59–61, 68–73

- Downey; Canepa, 59–60

- Vanden Berghe, Louis, Reliefs rupestres de l' Iran ancien, 1983, Brussels, per online summary of his list here Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Rawson, 45

- Downey

- Downey; Cotterell, 173–175; Rawson, 47

- Rostovtzeff: Dura and the Problem of Parthian Art; Downey

- H. T. Bakker (1987). Iconography of Religions. p. 7. ISBN 9789004047983.

- Fergus Millar (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. p. 329. ISBN 9780674778863. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- Cotterell, 175

- Harper; Cotterell, 177–178;

- Harper

- Keall

- Marshak, Boris I, "Panjicant" Archived 2015-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2002, Encyclopædia Iranica; Canby (1993), 9; Harper; many photos at warfare.ml Archived 2018-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Keall for Bishapur; see Harper for other sites

- Harper; Cotterell, 189–190

- Lerner, Judith A. "Sogdian Metalworking". Freer, Sackler - Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Sogdian art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 10 September 2012 [20 July 1998]. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Lerner, Judith A. "Orlat Plaques". Freer, Sackler - Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- Bellemare, Julie; Lerner, Judith A. "The Sogdians at Home - Art and Material Culture". Freer, Sackler - Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- Ettinghausen et al, 105, 133–135; Soucek

- Nishapur: Pottery of the Early Islamic Period, Wilkinson, Charles K. (1973)

- "Nishapur pottery". Archived from the original on 2015-06-10. Retrieved 2015-10-14.

- Ettinghausen et al, 105–116, 159–163, 165–166

- Ettinghausen et al, 166–171; Soucek; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 78–84, 64–73

- Ettinghausen et al, 125-127

- McWilliams, Mary. "Bowl Inscribed with a Saying of 'Ali ibn Abi Talib". Harvard Art Museums. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Volov, Lis (1966). "Plaited Kufic on Samanid Epigraphic Pottery". Ars Orientalis. 6 (1966): 107–33.

- Hillenbrand (1999), p.89; Soucek

- Hillenbrand (1999), p.91; Soucek

- Hillenbrand (1999), Chapter 4

- Piotrovsky & Rogers, 64–73

- Piotrovsky & Rogers, 78–93

- Hillenbrand, p.100

- Ettinghausen et al, 128–129, 162, 167; Soucek; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 50–62

- Canby (1993), 25–27

- Blair & Bloom, Chapter 3

- Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 661, 670. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Canby (1993), Chapter 3

- Blair & Bloom, Chapter 5

- Savory

- "UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity". Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- "UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity". Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- Canby (1993), Chapter 2

- Canby (1993), Chapters 3 and 4 respectively

- Canby (1993), Chapters 5–7

- Gray, 25-26, 48-49, 64

- Gruber, throughout; see Welch, 95–97 for one of the most famous examples, illustrated below

- In the terminiology of Western illuminated manuscripts, "illumination" usually covers both narrative scenes and decorative elements.

- Canby (1993), 83

- Welch

- Blair & Bloom, 171

- Canby (2009), 19-20

- Persian Drawings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1989. p. 3. ISBN 0870995642. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Blair & Bloom, 165–182

- Canby (1993), chapter 2; Blair & Bloom, 170–171

- Canby (1993), 77-86

- Canby (1993), 83-88

- Canby (1993), 91-101

- see Welch, 95-97

- Canby (2009), 101-104, 121-123, 137-159

- Canby (2009), 162-163, 218-219

- Blair & Bloom, 178; Canby (2009), 84-87

- Canby (2009), 237

- Canby (2009), 123

- Canby (2009), 160-161

- Canby (1993), 117–124; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 177-181; Scarce

- Canby (1993), 119–124; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 154-161; Scarce

- Canby (1993), 123

- A. Ashraf with Layla Diba, "Kamal-al-molk, Mohammad Gaffari Archived 2015-12-10 at the Wayback Machine, 2010–12, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Scarce; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 154

- Canby (1993), 119–124; Scarce; Piotrovsky & Rogers, 154

References

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

- Balafrej, Lamia. The Making of the Artist in Late Timurid Painting, Edinburgh University Press, 2019, ISBN 9781474437431

- Blair, Sheila, and Bloom, Jonathan M., The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250–1800, 1995, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300064659

- Canby, Sheila R. (ed), 2009, Shah Abbas; The Remaking of Iran, 2009, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124520

- Canby, Sheila R., 1993, Persian Painting, 1993, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714114590

- Canepa, Matthew P., "Topographies of Power, Theorizing the Visual, Spatial and Ritual Contexts of Rock Reliefs in Ancient Iran", in Harmanşah (2014), google books

- Cotterell, Arthur (ed), The Penguin Encyclopedia of Classical Civilizations, 1993, Penguin, ISBN 0670826995

- Curtis, John, The Oxus Treasure, British Museum Objects in Focus series, 2012, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714150796

- "Curtis and Tallis", Curtis, John and Tallis, Nigel (eds), Forgotten Empire – The World of Ancient Persia (catalogue of British Museum exhibition), 2005, University of California Press/British Museum, ISBN 9780714111575, google books

- Downey, S.B., "Art in Iran, iv., Parthian Art", Encyclopædia Iranica, 1986, Online text

- "EI I" = Muscarella, Oscar White, "Bronzes of Luristan", 1989, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, 2001, Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-08869-8

- Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072

- Gray, Basil, Persian Painting, Ernest Benn, London, 1930

- Gruber, Christiane, Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic painting, in Gulru Necipoglu, Karen Leal eds., Muqarnas, Volume 26, 2009, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-17589-X, 9789004175891, google books

- Harper, P.O., "History of Art in Iran, v. Sasanian", 1986–2011, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Herrmann, G, and Curtis, V.S., "Sasanian Rock Reliefs", Encyclopædia Iranica, 2002, Online text

- Hillenbrand, Robert. Islamic Art and Architecture, Thames & Hudson World of Art series; 1999, London. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7

- Keall, Edward J., "Bīšāpūr", 1989, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Jones, Dalu & Michell, George, (eds); The Arts of Islam, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1976, ISBN 0728700816

- Ledering, Joan, "Sasanian Rock Reliefs", http://www.livius.org

- Luschey, Heinz, "Bisotun ii. Archeology", Encyclopædia Iranica, 2013, Online text

- Muscarella, Oscar White, Bronze and Iron: Ancient Near Eastern Artifacts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870995251, 9780870995255, Google books

- Piotrovsky M.B. and Rogers, J.M. (eds), Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands, 2004, Prestel, ISBN 3791330551

- Porada, Edith, "Art in Iran i, Neolithic to Median", 1986–2011, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Rawson, Jessica, Chinese Ornament: The Lotus and the Dragon, 1984, British Museum Publications, ISBN 0714114316

- Savory, Roger, "Carpets i. Introductory survey; the history of Persian carpet manufacture", Encyclopædia Iranica

- Scarce, J.M., "Art in Iran x.1, Art and Architecture of the Qajar Period", 1986–2011, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Soucec, P., "Art in Iran vii, Islamic Pre-Safavid", 1986–2011, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292764847

- Welch, A, "Art in Iran ix, Safavid to Qajar Periods", 1986, Encyclopædia Iranica

- Welch, Stuart Cary, Royal Persian Manuscripts, Thames & Hudson, 1976, ISBN 0500270740

Further reading

- Roxburgh, David J.. 2003. "Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 43. [President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology]: 12–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20167587.

- Soucek, Priscilla P.. 1987. "Persian Artists in Mughal India: Influences and Transformations". Muqarnas 4. BRILL: 166–81. doi:10.2307/1523102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1523102.

%252C_1590s._By_Muhammad_Mu%E2%80%99min_MS_M.386.5r._Purchased_by_Pierpont_Morgan.jpg.webp)