Phenethylamine

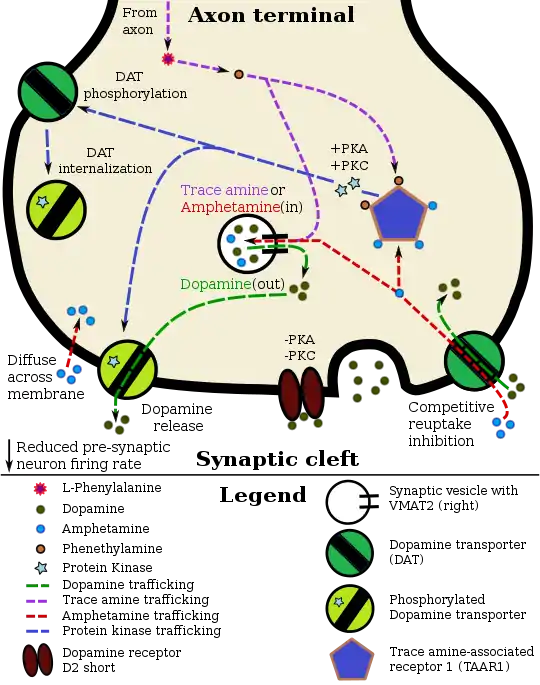

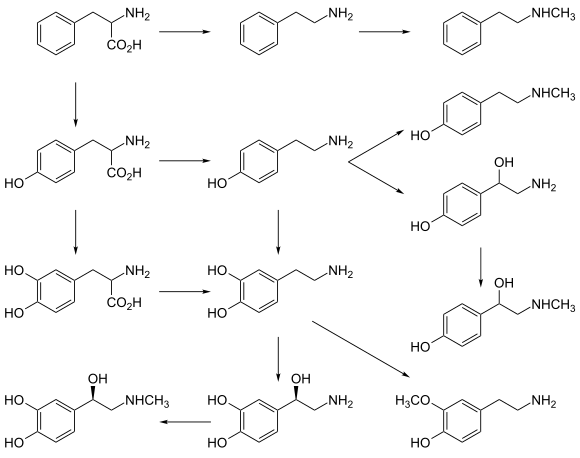

Phenethylamine[note 1] (PEA) is an organic compound, natural monoamine alkaloid, and trace amine, which acts as a central nervous system stimulant in humans. In the brain, phenethylamine regulates monoamine neurotransmission by binding to trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and inhibiting vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in monoamine neurons.[1][12][13] To a lesser extent, it also acts as a neurotransmitter in the human central nervous system.[14] In mammals, phenethylamine is produced from the amino acid L-phenylalanine by the enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase via enzymatic decarboxylation.[15] In addition to its presence in mammals, phenethylamine is found in many other organisms and foods, such as chocolate, especially after microbial fermentation.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /fɛnˈɛθələmiːn/ |

| Other names | PEA; phenylethylamine, phetamine |

| Dependence liability | Psychological: low–moderate Physical: none |

| Addiction liability | None–Low (w/o an MAO-B inhibitor)[1] Moderate (with an MAO-B inhibitor)[1] |

| Routes of administration | Oral (taken by mouth) |

| Drug class | CNSTooltip central nervous system stimulant |

| ATC code |

|

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | Substantia nigra pars compacta; Ventral tegmental area; Locus coeruleus; many others |

| Target tissues | System-wide |

| Receptors | Varies greatly across species; Human receptors: hTAAR1[2] |

| Precursor | L-Phenylalanine[3][4] |

| Biosynthesis | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC)[3][4] |

| Metabolism | Primarily: MAO-B[3][4][5] Other enzymes: MAO-A,[5][6] SSAOs (AOC2 & AOC3),[5][7] PNMT,[3][4][5] AANAT,[5] FMO3,[8][9] and others |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Primarily: MAO-B[3][4][5] Other enzymes: MAO-A,[5][6] SSAOs (AOC2 & AOC3),[5][7] PNMT,[3][4][5] AANAT,[5] FMO3,[8][9] and others |

| Elimination half-life | |

| Excretion | Renal (kidneys) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.523 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H11N |

| Molar mass | 121.183 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 0.9640 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −60 °C (−76 °F) [11] |

| Boiling point | 195 °C (383 °F) [11] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenethylamine is sold as a dietary supplement for purported mood and weight loss-related therapeutic benefits; however, in orally ingested phenethylamine, a significant amount is metabolized in the small intestine by monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) and then aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which converts it to phenylacetic acid.[5] This means that for significant concentrations to reach the brain, the dosage must be higher than for other methods of administration.[5][6][16] Some authors postulated its role in people's falling-in-love without substantiating it with any direct evidence.[17][18]

Phenethylamines, or more properly, substituted phenethylamines, are the group of phenethylamine derivatives that contain phenethylamine as a "backbone"; in other words, this chemical class includes derivative compounds that are formed by replacing one or more hydrogen atoms in the phenethylamine core structure with substituents. The class of substituted phenethylamines includes all substituted amphetamines, and substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamines (MDxx), and contains many drugs which act as empathogens, stimulants, psychedelics, anorectics, bronchodilators, decongestants, and/or antidepressants, among others.

Natural occurrence

Phenethylamine is produced by a wide range of species throughout the plant and animal kingdoms, including humans;[15][19] it is also produced by certain fungi and bacteria (genera: Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Pseudomonas and the family Enterobacteriaceae) and acts as a potent antimicrobial against certain pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli (e.g., the O157:H7 strain) at sufficient concentrations.[20]

Chemistry

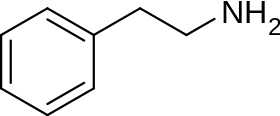

Phenethylamine is a primary amine, the amino-group being attached to a benzene ring through a two-carbon, or ethyl group.[21] It is a colourless liquid at room temperature that has a fishy odor, and is soluble in water, ethanol and ether.[21] Its density is 0.964 g/ml and its boiling point is 195 °C.[11] Upon exposure to air, it combines with carbon dioxide to form a solid carbonate salt.[22] Phenethylamine is strongly basic, pKb = 4.17 (or pKa = 9.83), as measured using the HCl salt, and forms a stable crystalline hydrochloride salt with a melting point of 217 °C.[21][23]

Substituted derivatives

Substituted phenethylamines are a chemical class of organic compounds based upon the phenethylamine structure;[note 2] the class is composed of all the derivative compounds of phenethylamine which can be formed by replacing, or substituting, one or more hydrogen atoms in the phenethylamine core structure with substituents.

Many substituted phenethylamines are psychoactive drugs, which belong to a variety of different drug classes, including central nervous system stimulants (e.g., amphetamine), hallucinogens (e.g., 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine), entactogens (e.g., 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine), appetite suppressants (e.g. phentermine), nasal decongestants and bronchodilators (e.g., pseudoephedrine), antidepressants (e.g. bupropion), antiparkinson agents (e.g., selegiline), and vasopressors (e.g., ephedrine), among others. Many of these psychoactive compounds exert their pharmacological effects primarily by modulating monoamine neurotransmitter systems; however, there is no mechanism of action or biological target that is common to all members of this subclass.

Numerous endogenous compounds – including hormones, monoamine neurotransmitters, and many trace amines (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, adrenaline, tyramine, and others) – are substituted phenethylamines. Dopamine is simply phenethylamine with a hydroxyl group attached to the 3 and 4 position of the benzene ring. Several notable recreational drugs, such as MDMA (ecstasy), methamphetamine, and cathinones, are also members of the class. All of the substituted amphetamines are phenethylamines, as well.

Pharmaceutical drugs that are substituted phenethylamines include phenelzine, phenformin, and fanetizole, among many others.

Synthesis

One method for preparing β-phenethylamine, set forth in J. C. Robinson and H. R. Snyder's Organic Syntheses (published 1955), involves the reduction of benzyl cyanide with hydrogen in liquid ammonia, in the presence of a Raney-Nickel catalyst, at a temperature of 130 °C and a pressure of 13.8 MPa. Alternative syntheses are outlined in the footnotes to this preparation.[24]

A much more convenient method for the synthesis of β-phenethylamine is the reduction of ω-nitrostyrene by lithium aluminium hydride in ether, whose successful execution was first reported by R. F. Nystrom and W. G. Brown in 1948.[25]

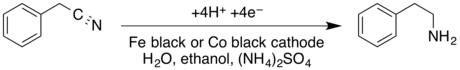

Phenethylamine can also be produced via the cathodic reduction of benzyl cyanide in a divided cell.[26]

Assembling phenethylamine structures for synthesis of compounds such as epinephrine, amphetamines, tyrosine, and dopamine by adding the beta-aminoethyl side chain to the phenyl ring is possible. This can be done via Friedel-Crafts acylation with N-protected acyl chlorides when the arene is activated, or by Heck reaction of the phenyl with N-vinyloxazolone, followed by hydrogenation, or by cross-coupling with beta-amino organozinc reagents, or reacting a brominated arene with beta-aminoethyl organolithium reagents, or by Suzuki cross-coupling.[27]

Detection in body fluids

Reviews that cover attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and phenethylamine indicate that several studies have found abnormally low urinary phenethylamine concentrations in ADHD individuals when compared with controls.[28] In treatment-responsive individuals, amphetamine and methylphenidate greatly increase urinary phenethylamine concentration.[28] An ADHD biomarker review also indicated that urinary phenethylamine levels could be a diagnostic biomarker for ADHD.[28]

Thirty minutes of moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise has been shown to induce an increase in urinary phenylacetic acid, the primary metabolite of phenethylamine.[3][29][30] Two reviews noted a study where the mean 24 hour urinary phenylacetic acid concentration following just 30 minutes of intense exercise rose 77% above its base level;[3][29][30] the reviews suggest that phenethylamine synthesis sharply increases during physical exercise during which it is rapidly metabolized due to its short half-life of roughly 30 seconds.[3][29][30][4] In a resting state, phenethylamine is synthesized in catecholamine neurons from L-phenylalanine by aromatic amino acid decarboxylase at approximately the same rate as dopamine is produced.[4] Monoamine oxidase deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone. Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B, which is not found in the gut. Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin, but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate.[15] Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life. Because of the pharmacological relationship between phenethylamine and amphetamine, the original paper and both reviews suggest that phenethylamine plays a prominent role in mediating the mood-enhancing euphoric effects of a runner's high, as both phenethylamine and amphetamine are potent euphoriants.[3][29][30]

Skydiving has also been shown to induce a marked increase in urinary phenethylamine concentrations.[21][31]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Phenethylamine pharmacodynamics in a TAAR1–dopamine neuron

|

Phenethylamine, being similar to amphetamine in its action at their common biomolecular targets, releases norepinephrine and dopamine.[12][13][35] Phenethylamine also appears to induce acetylcholine release via a glutamate-mediated mechanism.[36]

Phenethylamine has been shown to bind to human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1) as an agonist.[2] β-PEA is also an odorant binding TAAR4 in mice thought to mediate predator avoidance.[37]

Pharmacokinetics

By oral route, phenethylamine's half-life is 5–10 minutes;[10] endogenously produced PEA in catecholamine neurons has a half-life of roughly 30 seconds.[3] In humans, PEA is metabolized by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT),[3][4][5][41] monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A),[5][6] monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B),[3][4][5][16] the semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidases (SSAOs) AOC2 and AOC3,[5][7] flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3),[8][9] and aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT).[5][42] N-Methylphenethylamine, an isomer of amphetamine, is produced in humans via the metabolism of phenethylamine by PNMT.[3][4][41] β-Phenylacetic acid is the primary urinary metabolite of phenethylamine and is produced via monoamine oxidase metabolism and subsequent aldehyde dehydrogenase metabolism.[5] Phenylacetaldehyde is the intermediate product which is produced by monoamine oxidase and then further metabolized into β-phenylacetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase.[5][43]

When the initial phenylethylamine concentration in the brain is low, brain levels can be increased 1000-fold when taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), particularly a MAO-B inhibitor, and by 3–4 times when the initial concentration is high.[44]

Notes

- Synonyms and alternate spellings include: phenylethylamine, β-phenylethylamine (β-PEA), 2-phenylethylamine, 1-amino-2-phenylethane, and 2-phenylethan-1-amine.

- In other words, all of the compounds that belong to this class are structural analogs of phenethylamine.

References

- Pei Y, Asif-Malik A, Canales JJ (April 2016). "Trace Amines and the Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1: Pharmacology, Neurochemistry, and Clinical Implications". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10: 148. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00148. PMC 4820462. PMID 27092049.

Furthermore, evidence has accrued on the ability of TAs to modulate brain reward (i.e., the subjective experience of pleasure) and reinforcement (i.e., the strengthening of a conditioned response by a given stimulus; Greenshaw, 2021), suggesting the involvement of the TAs in the neurological adaptations underlying drug addiction, a chronic relapsing syndrome characterized by compulsive drug taking, inability to control drug intake and dysphoria when access to the drug is prevented (Koob, 2009). Consistent with its hypothesized role as "endogenous amphetamine," β-PEA was shown to possess reinforcing properties, a defining feature that underlies the abuse liability of amphetamine and other psychomotor stimulants. β-PEA was also as effective as amphetamine in its ability to produce conditioned place preference (i.e., the process by which an organism learns an association between drug effects and a particular place or context) in rats (Gilbert and Cooper, 1983) and was readily self-administered by dogs that had a stable history (i.e., consisting of early acquisition and later maintenance) of amphetamine or cocaine self-administration (Risner and Jones, 1977; Shannon and Thompson, 1984). In another study, high concentrations of β-PEA dose-dependently maintained responding in monkeys that were previously trained to self-administer cocaine, and pretreatment with a MAO-B inhibitor, which delayed β-PEA deactivation, further increased response rates (Bergman et al., 2001).

- Khan MZ, Nawaz W (October 2016). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 83: 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. PMID 27424325.

- Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

The pharmacology of TAs might also contribute to a molecular understanding of the well-recognized antidepressant effect of physical exercise [51]. In addition to the various beneficial effects for brain function mainly attributed to an upregulation of peptide growth factors [52,53], exercise induces a rapidly enhanced excretion of the main β-PEA metabolite β-phenylacetic acid (b-PAA) by on average 77%, compared with resting control subjects [54], which mirrors increased β-PEA synthesis in view of its limited endogenous pool half-life of ~30 s [18,55].

- Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase

- Wishart, David S.; Guo, An Chi; Oler, Eponine; Wang, Fel; Anjum, Afia; Peters, Harrison; Dizon, Raynard; Sayeeda, Zinat; Tian, Siyang; Lee, Brian L.; Berjanskii, Mark; Mah, Robert; Yamamoto, Mai; Jovel Castillo, Juan; Torres Calzada, Claudia; Hiebert Giesbrecht, Mickel; Lui, Vicki W.; Varshavi, Dorna; Varshavi, Dorsa; Allen, Dana; Arndt, David; Khetarpal, Nitya; Sivakumaran, Aadhavya; Harford, Karxena; Sanford, Selena; Yee, Kristen; Cao, Xuan; Budinsky, Zachary; Liigand, Jaanus; Zhang, Lun; Zheng, Jiamin; Mandal, Rupasri; Karu, Naama; Dambrova, Maija; Schiöth, Helgi B.; Gautam, Vasuk. "Showing metabocard for Phenylethylamine (HMDB0012275)". Human Metabolome Database, HMDB. 5.0.

- Suzuki O, Katsumata Y, Oya M (March 1981). "Oxidation of beta-phenylethylamine by both types of monoamine oxidase: examination of enzymes in brain and liver mitochondria of eight species". Journal of Neurochemistry. 36 (3): 1298–1301. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb01734.x. PMID 7205271. S2CID 36099388.

- Kaitaniemi S, Elovaara H, Grön K, Kidron H, Liukkonen J, Salminen T, et al. (August 2009). "The unique substrate specificity of human AOC2, a semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 66 (16): 2743–2757. doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0076-5. PMID 19588076. S2CID 30090890.

The preferred in vitro substrates of AOC2 were found to be 2-phenylethylamine, tryptamine and p-tyramine instead of methylamine and benzylamine, the favored substrates of AOC3.

- Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

The biogenic amines, phenethylamine and tyramine, are N-oxygenated by FMO to produce the N-hydroxy metabolite, followed by a rapid second oxygenation to produce the trans-oximes (Lin & Cashman, 1997a, 1997b). This stereoselective N-oxygenation to the trans-oxime is also seen in the FMO-dependent N-oxygenation of amphetamine (Cashman et al., 1999) ... Interestingly, FMO2, which very efficiently N-oxygenates N-dodecylamine, is a poor catalyst of phenethylamine N-oxygenation. The most efficient human FMO in phenethylamine N-oxygenation is FMO3, the major FMO present in adult human liver; the Km is between 90 and 200 μM (Lin & Cashman, 1997b).

- Robinson-Cohen C, Newitt R, Shen DD, Rettie AE, Kestenbaum BR, Himmelfarb J, Yeung CK (August 2016). "Association of FMO3 Variants and Trimethylamine N-Oxide Concentration, Disease Progression, and Mortality in CKD Patients". PLOS ONE. 11 (8): e0161074. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161074R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161074. PMC 4981377. PMID 27513517.

TMAO is generated from trimethylamine (TMA) via metabolism by hepatic flavin-containing monooxygenase isoform 3 (FMO3). ... FMO3 catalyzes the oxidation of catecholamine or catecholamine-releasing vasopressors, including tyramine, phenylethylamine, adrenaline, and noradrenaline [32, 33].

- "Phenethylamine: Pharmacology and Biochemistry". PubChem. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Plasma Pharmacokinetics of PEA Could Be Described By 1st-Order Kinetics With Estimated T/2 of Approx 5-10 Min.

- "Chemical and Physical Properties". Phenethylamine.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Wimalasena K (July 2011). "Vesicular monoamine transporters: structure-function, pharmacology, and medicinal chemistry". Medicinal Research Reviews. 31 (4): 483–519. doi:10.1002/med.20187. PMC 3019297. PMID 20135628.

Phenylethylamine (10), amphetamine [AMPH (11 & 12)], methylenedioxy methamphetamine [METH (13)] and N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (15) are all more potent inhibitors of VMAT2...

- Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- Sabelli HC, Mosnaim AD, Vazquez AJ, Giardina WJ, Borison RL, Pedemonte WA (August 1976). "Biochemical plasticity of synaptic transmission: a critical review of Dale's Principle". Biological Psychiatry. 11 (4): 481–524. PMID 9160.

- Berry MD (July 2004). "Mammalian central nervous system trace amines. Pharmacologic amphetamines, physiologic neuromodulators". Journal of Neurochemistry. 90 (2): 257–271. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02501.x. PMID 15228583.

- Yang HY, Neff NH (November 1973). "Beta-phenylethylamine: a specific substrate for type B monoamine oxidase of brain". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 187 (2): 365–371. PMID 4748552.

- Godfrey PD, Hatherley LD, Brown RD (1 August 1995). "The Shapes of Neurotransmitters by Millimeter-Wave Spectroscopy: 2-Phenylethylamine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 117 (31): 8204–8210. doi:10.1021/ja00136a019. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Marazziti D, Canale D (August 2004). "Hormonal changes when falling in love". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 29 (7): 931–936. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.006. PMID 15177709. S2CID 24651931.

- Smith TA (1977). "Phenethylamine and related compounds in plants". Phytochemistry. 16 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(77)83004-5.

- Lynnes T, Horne SM, Prüß BM (January 2014). "ß-Phenylethylamine as a novel nutrient treatment to reduce bacterial contamination due to Escherichia coli O157:H7 on beef meat". Meat Science. 96 (1): 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.06.030. PMID 23896151.

Acetoacetic acid (AAA) and ß-phenylethylamine (PEA) performed best in this experiment. On beef meat pieces, PEA reduced the bacterial cell count by 90% after incubation of the PEA-treated and E. coli-contaminated meat pieces at 10°C for one week.

- Phenethylamine. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - O'Neil MJ, ed. (2001). The Merck Index – An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (13th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and Co., Inc. p. 1296.

- Leffler EB, Spencer HM, Burger A (1951). "Dissociation Constants of Adrenergic Amines". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (6): 2611–3. doi:10.1021/ja01150a055.

- Robinson JC, Snyder HR (1955). "β-Phenylethylamine" (PDF). Organic Syntheses, Collected Volume. 3: 720.

- Nystrom RF, Brown WG (November 1948). "Reduction of organic compounds by lithium aluminum hydride; halides, quinones, miscellaneous nitrogen compounds". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 70 (11): 3738–3740. doi:10.1021/ja01191a057. PMID 18102934.

- Krishnan V, Muthukumaran A, Udupa HV (1979). "The electroreduction of benzyl cyanide on iron and cobalt cathodes". Journal of Applied Electrochemistry. 9 (5): 657–659. doi:10.1007/BF00610957. S2CID 96102382.

- Molander GA, Vargas F (January 2007). "Beta-aminoethyltrifluoroborates: efficient aminoethylations via Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling". Organic Letters. 9 (2): 203–206. doi:10.1021/ol062610v. PMC 2593899. PMID 17217265.

- Scassellati C, Bonvicini C, Faraone SV, Gennarelli M (October 2012). "Biomarkers and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 51 (10): 1003–1019.e20. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.015. PMID 23021477.

Although we did not find a sufficient number of studies suitable for a meta-analysis of PEA and ADHD, three studies20,57,58 confirmed that urinary levels of PEA were significantly lower in patients with ADHD compared with controls. ... Administration of D-amphetamine and methylphenidate resulted in a markedly increased urinary excretion of PEA,20,60 suggesting that ADHD treatments normalize PEA levels. ... Similarly, urinary biogenic trace amine PEA levels could be a biomarker for the diagnosis of ADHD,20,57,58 for treatment efficacy,20,60 and associated with symptoms of inattentivenesss.59 ... With regard to zinc supplementation, a placebo controlled trial reported that doses up to 30 mg/day of zinc were safe for at least 8 weeks, but the clinical effect was equivocal except for the finding of a 37% reduction in amphetamine optimal dose with 30 mg per day of zinc.110

- Szabo A, Billett E, Turner J (October 2001). "Phenylethylamine, a possible link to the antidepressant effects of exercise?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 35 (5): 342–343. doi:10.1136/bjsm.35.5.342. PMC 1724404. PMID 11579070.

The 24 hour mean urinary concentration of phenylacetic acid was increased by 77% after exercise. ... These results show substantial increases in urinary phenylacetic acid levels 24 hours after moderate to high intensity aerobic exercise. As phenylacetic acid reflects phenylethylamine levels3, and the latter has antidepressant effects, the antidepressant effects of exercise appear to be linked to increased phenylethylamine concentrations. Furthermore, considering the structural and pharmacological analogy between amphetamines and phenylethylamine, it is conceivable that phenylethylamine plays a role in the commonly reported "runners high" thought to be linked to cerebral β-endorphin activity. The substantial increase in phenylacetic acid excretion in this study implies that phenylethylamine levels are affected by exercise. ... A 30 minute bout of moderate to high intensity aerobic exercise increases phenylacetic acid levels in healthy regularly exercising men. The findings may be linked to the antidepressant effects of exercise.

- Berry MD (January 2007). "The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 2 (1): 3–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.329.563. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. PMID 18473983.

It has also been suggested that the antidepressant effects of exercise are due to an exercise-induced elevation of PE [151].

- Paulos MA, Tessel RE (February 1982). "Excretion of beta-phenethylamine is elevated in humans after profound stress". Science. 215 (4536): 1127–1129. Bibcode:1982Sci...215.1127P. doi:10.1126/science.7063846. PMID 7063846.

The urinary excretion rate of the endogenous, amphetamine-like substance beta-phenethylamine was markedly elevated in human subjects in association with an initial parachuting experience. The increases were delayed in most subjects and were not correlated with changes in urinary pH or creatinine excretion.

- 2-PHENYLETHYLAMINE. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Erickson JD, Schafer MK, Bonner TI, Eiden LE, Weihe E (May 1996). "Distinct pharmacological properties and distribution in neurons and endocrine cells of two isoforms of the human vesicular monoamine transporter". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (10): 5166–5171. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.5166E. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.10.5166. PMC 39426. PMID 8643547.

- Offermanns, S; Rosenthal, W, eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer. pp. 1219–1222. ISBN 978-3540389163.

- Gozal EA, O'Neill BE, Sawchuk MA, Zhu H, Halder M, Chou CC, Hochman S (2014). "Anatomical and functional evidence for trace amines as unique modulators of locomotor function in the mammalian spinal cord". Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 8: 134. doi:10.3389/fncir.2014.00134. PMC 4224135. PMID 25426030.

TAAR1 activity appears to depress monoamine transport and limit dopaminergic and serotonergic neuronal firing rates via interactions with presynaptic D2 and 5-HT1A autoreceptors, respectively (Wolinsky et al., 2007; Lindemann et al., 2008; Xie and Miller, 2008; Xie et al., 2008; Bradaia et al., 2009; Revel et al., 2011; Leo et al., 2014). ... TAAR1 and TAAR4 labeling in all neurons appeared intracellular, consistent with previous reported results for TAAR1 (Miller, 2011). A cytoplasmic location of ligand and receptor (e.g., tyramine and TAAR1) supports intracellular activation of signal transduction pathways, as suggested previously (Miller, 2011). ... Additionally, once transported intracellularly, they could act on presynaptic TAARs to alter basal activity (Miller, 2011). ... As reported for TAAR1 in HEK cells (Bunzow et al., 2001; Miller, 2011), we observed cytoplasmic labeling for TAAR1 and TAAR4, both of which are activated by the TAs (Borowsky et al., 2001). A cytoplasmic location of the ligand and the receptor (e.g., tyramine and TAAR1) would support intracellular activation of signal transduction pathways (Miller, 2011). Such a co-localization would not require release from vesicles and could explain why the TAs do not appear to be found there (Berry, 2004; Burchett and Hicks, 2006).

- Deepak N, Sara T, Andrew H, Darrell DM, Glen BB (2011). "Trace amines and their relevance to psychiatry and neurology: a brief overview". Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (1): 73–79. doi:10.5350/KPB-BCP201121113.

PEA can also stimulate acetylcholine release through activation of glutamatergic signaling pathways (21), and PEA and p-TA have been reported to depress GABAB receptor-mediated responses in dopaminergic neurons (22,23). Although PEA, T and p-TA have been reported to be present in synaptosomes (nerve ending preparations isolated during homogenization and centrifugation of brain tissue) (24), research with reserpine and neurotoxins suggests that m- and p-TA may be stored in vesicles while PEA and T are not (25–27). ... the antidepressant effects of exercise have been suggested to be due to an elevation of PEA (57). l-Deprenyl (selegiline), a selective inhibitor of MAO-B, is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and produces a marked increase in brain levels of PEA relative to other amines (20,58). ... Interestingly, the gene for aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), the major enzyme involved in the synthesis of the trace amines, is located in the same region of chromosome 7 that has been proposed as a susceptibility locus for ADHD (50)

- Liberles SD (October 2015). "Trace amine-associated receptors: ligands, neural circuits, and behaviors". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 34: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2015.01.001. PMC 4508243. PMID 25616211.

- Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- Pendleton RG, Gessner G, Sawyer J (September 1980). "Studies on lung N-methyltransferases, a pharmacological approach". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 313 (3): 263–268. doi:10.1007/BF00505743. PMID 7432557. S2CID 1015819.

- "EC 2.3.1.87 – Aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase". BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. July 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Aldehyde dehydrogenase – Homo sapiens. January 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - Sabelli HC, Borison RL, Diamond BI, Havdala HS, Narasimhachari N (1978). "Phenylethylamine and brain function". Biochemical Pharmacology. 27 (13): 1707–1711. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(78)90543-9. PMID 361043.