Philolaus

Philolaus (/ˌfɪləˈleɪəs/; Ancient Greek: Φιλόλαος, Philólaos; c. 470 – c. 385 BCE)[1][2] was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and the most outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras developed a school of philosophy that was dominated by both mathematics and mysticism. Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views. He may have been the first to write about Pythagorean doctrine. According to August Böckh (1819), who cites Nicomachus, Philolaus was the successor of Pythagoras.[3]

Philolaus | |

|---|---|

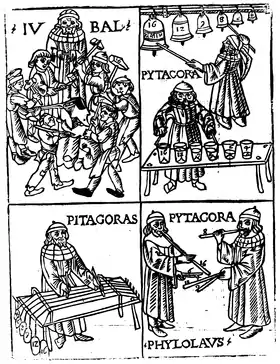

Medieval woodcut by Franchino Gaffurio, depicting Pythagoras and Philolaus conducting musical investigations | |

| Born | c. 470 BCE |

| Died | c. 385 BCE |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Pythagoreanism |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

He argued that at the foundation of everything is the part played by the limiting and limitless, which combine in a harmony. With his assertions that the Earth was not the center of the universe (geocentrism), he is credited with the earliest known discussion of concepts in the development of heliocentrism, the theory that the Earth is not the center of the Universe, but rather that the Sun is. Philolaus discussed a Central Fire as the center of the universe and that spheres (including the Sun) revolved around it.

Biography

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton,[4] Tarentum,[5] or Metapontum[6]—all part of Magna Graecia (the name of the coastal areas of Southern Italy on the Tarentine Gulf that were colonized extensively by Greek settlers). It is most likely that he came from Croton.[7][8] He migrated to Greece, perhaps while fleeing the second burning of the Pythagorean meeting-place around 454 BC.[9]

According to Plato's Phaedo, he was the instructor of Simmias and Cebes at Thebes, around the time the Phaedo takes place, in 399 BC.[10] That would make him a contemporary of Socrates, and would agree with the statement that Philolaus and Democritus were contemporaries.[11]

The writings of much later writers are the sources of further reports about his life. They are scattered and of dubious value in reconstructing his life. Apparently, he lived for some time at Heraclea, where he was the pupil of Aresas, or (as Plutarch calls him) Arcesus.[12] Diogenes Laërtius is the only authority for the claim that shortly after the death of Socrates, Plato traveled to Italy where he met with Philolaus and Eurytus.[13] The pupils of Philolaus were said to have included Xenophilus, Phanto, Echecrates, Diocles, and Polymnastus.[14]

As to his death, Diogenes Laërtius reports a dubious story that Philolaus was put to death at Croton on account of being suspected of wanting to be the tyrant;[15] a story which Diogenes Laërtius even chose to put into verse.[16]

Writings

Pythagoras and his earliest successors do not appear to have committed any of their doctrines to writing. According to Porphyrius (Vit. Pyth. p. 40) Lysis and Archippus collected in a written form some of the principal Pythagorean doctrines, which were handed down as heirlooms in their families, under strict injunctions that they should not be made public. But amid the different and inconsistent accounts of the matter, the first publication of the Pythagorean doctrines is pretty uniformly attributed to Philolaus.[17]

In one source, Diogenes Laërtius speaks of Philolaus composing one book,[18] but elsewhere he speaks of three books,[19] as do Aulus Gellius and Iamblichus. It might have been one treatise divided into three books. Plato is said to have procured a copy of his book. Later, it was claimed that Plato composed much of his Timaeus based upon the book by Philolaus.[20]

One of the works of Philolaus was called On Nature.[18] It seems to be the same work that Stobaeus calls On the World and from which he has preserved a series of passages.[21] Other writers refer to a work entitled Bacchae, which may have been another name for the same work, and which may originate from Arignote. However, it has been mentioned that Proclus describes the Bacchae as a book for teaching theology by means of mathematics.[7] It appears, in fact, from this, as well as from the extant fragments, that the first book of the work contained a general account of the origin and arrangement of the universe. The second book appears to have been an exposition of the nature of numbers, which in the Pythagorean theory are the essence and source of all things.[22]

He composed a work on the Pythagorean philosophy in three books, which Plato is said to have procured at the cost of 100 minae through Dion of Syracuse, who purchased it from Philolaus, who was at the time in deep poverty.[23] Other versions of the story represent Plato as purchasing it himself from Philolaus or his relatives when in Sicily. [24] Out of the materials which he derived from these books Plato is said to have composed his Timaeus. But in the age of Plato the leading features of the Pythagorean doctrines had long ceased to be a secret; and if Philolaus taught the Pythagorean doctrines at Thebes, he was hardly likely to feel much reluctance in publishing them; and amid the conflicting and improbable accounts preserved in the authorities above referred to, little more can be regarded as trustworthy, except that Philolaus was the first who published a book on the Pythagorean doctrines, and that Plato read and made use of it. [25] Historians from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Chapter Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia, noted the following:[7]

It is implied that these books were not by Philolaus himself, and it seems likely that the statement refers to three spurious works assigned to Pythagoras at D.L. VIII 6 (Burkert 1972a, 224–5). The story of Plato's purchase of these books from Philolaus was probably invented to authenticate the three forged treatises of Pythagoras. Burkert's arguments (1972a, 238–277), supported by further study (Huffman 1993), have led to a consensus that some 11 fragments are genuine (Frs. 1–6, 6a, 7, 13, 16 and 17 in the numbering of Huffman 1993) and derive from Philolaus' book On Nature (Barnes 1982; Kahn 1993 and 2001; Kirk, Raven and Schofield 1983; Nussbaum 1979; Zhmud 1997). Fragments 1, 6a and 13 are identified as coming from the book On Nature by ancient sources. Stobaeus cites fragments 2 and 4–7 as coming from a work On the Cosmos, but this appears to be an alternate title for On Nature, which probably arose because the chapter heading in Stobaeus under which the fragments are cited is 'On the Cosmos.'

Philosophy

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting;[27] for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge.[28] Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (harmonia):

This is the state of affairs about nature and harmony. The essence of things is eternal; it is a unique and divine nature, the knowledge of which does not belong to Man. Still it would not be possible that any of the things that are, and are known by us, should arrive to our knowledge, if this essence was not the internal foundation of the principles of which the world was founded, that is, of the limiting and unlimited elements. Now since these principles are not mutually similar, neither of similar nature, it would be impossible that the order of the world should have been formed by them, unless the harmony intervened [...].

— Philolaus, Fragment DK 44B 6a.

Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:[29]

Philolaus is trying to show how the ordered universe that we know came into its present condition. It arose, he says, by the action of harmony on a basic substance, which we do not know but must infer. This substance consisted of different primary elements, and harmony fitted these together in such a way that nature φύσις turns out to be an ordered world κόσμος.

The book by Philolaus begins with the following:[7]

Nature (physis) in the world-order (cosmos) was fitted together out of things which are unlimited and out of things which are limiting, both the world-order as a whole and everything in it.

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around a hypothetical astronomical object he called the Central Fire.

Philolaus says that there is fire in the middle at the centre [...] and again more fire at the highest point and surrounding everything. By nature the middle is first, and around it dance ten divine bodies—the sky, the planets, then the sun, next the moon, next the earth, next the counterearth, and after all of them the fire of the hearth which holds position at the centre. The highest part of the surrounding, where the elements are found in their purity, he calls Olympus; the regions beneath the orbit of Olympus, where are the five planets with the sun and the moon, he calls the world; the part under them, being beneath the moon and around the earth, in which are found generation and change, he calls the sky.

— Stobaeus, i. 22. 1d

In Philolaus's system a sphere of the fixed stars, the five planets, the Sun, Moon, and Earth, all moved around a Central Fire. According to Aristotle, writing in Metaphysics, Philolaus added a tenth unseen body, he called Counter-Earth, as without it there would be only nine revolving bodies, and the Pythagorean number theory required a tenth. However, Greek scholar George Burch asserts his belief that Aristotle was lampooning Philolaus's addition.

The system that Philolaus described predated the idea of spheres by hundreds of years, however.[30] Nearly two-thousand years later, Nicolaus Copernicus would mention in De revolutionibus that Philolaus already knew about the Earth's revolution around a central fire.

It has been pointed out, however, that Stobaeus betrays a tendency to confound the dogmas of the early Ionian philosophers, and in his accounts, he occasionally mixes up Platonism with Pythagoreanism.[31]

Notes

- Huffman, Carl (2020), "Philolaus", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- "The most likely date for Philolaus' birth would then appear to be around 470, although he could have been born as early as 480 or as late as 440. He appears to have lived into the 380s and at the very least until 399." Carl A. Huffman, (1993) Philolaus of Croton: Pythagorean and Presocratic, pages 5–6. Cambridge University Press

- Böckh, August (1819). Philolaos des Pythagoreers Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken seines Werkes. In der Vossischen Buchhandlung. p. 14.

Pythagoras Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken seines Werkes.

- Iamblichus, Vita Pythagorica, p. 148

- Iamblichus, Vita Pythagorica, p. 267; Diogenes Laërtius, viii, p. 46

- Iamblichus, Vita Pythagorica, pp. 266–67

- Carl Huffman. "Philolaus". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Carl A. Huffman, (1993) Philolaus of Croton: Pythagorean and Presocratic, p. 6. Cambridge University Press

- Not to be confused with the first burning of the meeting place, in the lifetime of Pythagoras, c. 509 BC

- Plato, Phaedo, 61DE

- Apollodorus ap. Diogenes Laërtius, ix. 38

- Iamblichus, Vita Pythagorica; comp. Plutarch, de Gen. Socr. 13, although the account given by Plutarch involves great inaccuracies

- Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 6

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 46

- "The story at D.L. 84 that Philolaus was killed because he was thought to be aiming at a tyranny is clearly a confusion with Dion who is mentioned in the context and did have such a death." Carl A. Huffman, (1993) Philolaus of Croton: Pythagorean and Presocratic, p. 6. Cambridge University Press

- Diogenes Laërtius, iii. p. 84; cf. Suda, Philolaus

-

Charles Peter Mason (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

Charles Peter Mason (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 85

- Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 9, viii. 15

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 15, 55, 84, 85, iii. 9; Aulus Gellius, iii. 17; Iamblichus, Vita Pythagorica; Tzetzes, Chiliad, x. 792, xi. 38

- DK 44 B 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

-

Charles Peter Mason (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

Charles Peter Mason (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

-

[Charles Peter Mason]] (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

[Charles Peter Mason]] (1870). "Philolaus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

- (Diog. Laert. viii. 15, 55, 84, 85, iii. 9; A. Gellius,iV. iii. 17; lamblichus, Vit. Fyth. 31. p. 172 ; Tzetzes, Chiliad, x. 792, &c. xi. 38, &c.)

- (Böckh, I.e. p. 22.)

- Gaffurius, Franchinus (1492). Theorica musicae.

- Fragment DK 44B 1

- Fragment DK 44B 3

- Scoon, Robert (1922). Philolaus, Fragment 6, Diels. Stobaeus i. 21. 460. Classical Philology.

- Burch, George Bosworth. The Counter-Earth Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stobaeus, Joannes". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

External links

Quotations related to Philolaus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Philolaus at Wikiquote Works by or about Philolaus at Wikisource

Works by or about Philolaus at Wikisource Media related to Philolaus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Philolaus at Wikimedia Commons- Huffman, Carl. "Philolaus". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 414.