Phoenice (Roman province)

Phoenice (Latin: Syria Phoenīcē Latin: [ˈsʏri.a pʰoe̯ˈniːkeː]; Koinē Greek: ἡ Φοινίκη Συρία, romanized: hē Phoinī́kē Syría Koinē Greek: [(h)e pʰyˈni.ke syˈri.a]) was a province of the Roman Empire, encompassing the historical region of Phoenicia. It was officially created in 194 AD and after c. 394, Phoenice Syria was divided into Phoenice proper or Phoenice Paralia, and Phoenice Libanensis, a division that persisted until the region was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in the 630s.

| Province of Syria Phoenice | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire (after 395 of the Byzantine Empire) | |||||||||||||

| c. 194–c. 394 | |||||||||||||

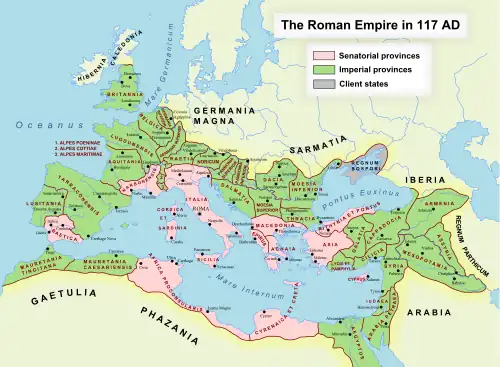

.svg.png.webp) Roman Empire in 210 with Syria Phoenice highlighted in red | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Tyrus | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Created by Septimius Severus | c. 194 | ||||||||||||

• Division during the reign of Theodosius the Great | c. 394 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Lebanon Israel | ||||||||||||

Administrative history

Phoenicia came under Roman rule in 64 BC, when Pompey created the province of Syria. With the exception of a brief period in 36–30 BC, when Mark Antony gave the region to Ptolemaic Egypt, Phoenicia remained part of the province of Syria thereafter.[1] Emperor Hadrian (reigned 117–138) is said to have considered a division of the overly large Syrian province in 123–124 AD, but it was not until shortly after c. 194 AD that Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) actually undertook this, dividing the province into Syria Coele in the north and Syria Phoenice in the south.[1] Tyre became the capital of the new province, but Elagabalus (r. 218–222) raised his native Emesa to co-capital, and the two cities rivalled each other as the head of the province until its division in the 4th century.[1]

The province was much larger than the area traditionally called Phoenicia: for example, cities like Emesa[lower-alpha 1] and Palmyra[lower-alpha 2] and the base of the Legio III Gallica[lower-alpha 3] in Raphanaea[lower-alpha 4] were now subject to governor in Tyre. Veterans of this military unit were settled in Tyre, which also received the rank of colonia.[2]

After the death of the 2nd century Roman emperor Commodus, a civil war erupted, in which Berytus, and Sidon supported Pescennius Niger. While the city of Tyre supported Septimius Severus, which led Niger to send Mauri[lower-alpha 5] javelin men and archers to sack the city.[3] However, Niger lost the civil war, and Septimius Severus decided to show his gratitude for Tyre's support by making it the capital of Phoenice.

Diocletian (r. 284–305) separated the district of Batanaea and gave it to Arabia, while sometime before 328, when it is mentioned in the Laterculus Veronensis, Constantine the Great (r. 306–337) created the new province of Augusta Libanensis out of the eastern half of the old province, encompassing the territory east of Mount Lebanon.[4]

Phoenice I and Phoenice Libanensis

Constantine's province was short-lived, but formed the basis of the re-division of Phoenice c. 394 into the Phoenice I or Phoenice Paralia (Greek: Φοινίκη Παραλία, "coastal Phoenice"), and Phoenice II or Phoenice Libanensis (Φοινίκη Λιβανησία), with Tyre and Emesa as their respective capitals.[4] In the Notitia Dignitatum, written shortly after the division, Phoenice I is governed by a consularis, while Libanensis is governed by a praeses, with both provinces under the Diocese of the East.[5] This division remained intact until the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s.[6] Under the Caliphate, most of the two Phoenices came under the province of Damascus, with parts in the south and north going to the provinces of Jordan and Emesa respectively.[7]

Ecclesiastical administration

The ecclesiastical administration paralleled the political, but with some differences. The bishop of Tyre emerged as the pre-eminent prelate of Phoenice by the mid-3rd century. When the province was divided c. 394, Damascus, rather than Emesa, became the metropolis of Phoenice II. Both provinces belonged to the Patriarchate of Antioch, with Damascus initially outranking Tyre, whose position was also briefly challenged by the see of Berytus c. 450; after 480/1, however, the Metropolitan of Tyre established himself as the first in precedence (protothronos) of all the Metropolitans subject to Antioch.[6]

Military

Since the time of Septimius Severus, it had been the practice to assign not more than two legions to each frontier province, and, although in some provinces one legion was sometimes deemed sufficient, the upper limit was not exceeded. This policy appears to have been continued during the third century AD, as seen in the case of Aurelian raising the garrisons of Phoenice to the normal strength of two legions.[8]

Governors

Propraetorial Imperial Legates of Phoenicia

| Date | Legatus Augusti pro praetore (Governor of imperial province) |

|---|---|

| 193 – 194 | Ti. Manilius Fuscus[9] |

| 198 | Q. Venidius Rufus Marius Maximus L. Calvinianus |

| c. 207 | Domitius Leo Procillianus |

| 213 | D. Pius Cassius |

| Between 268 and 270 | Salvius Theodorus |

| Between 284 and 305 | L. Artorius Pius Maximus |

| 292 – 293 | Crispinus |

Consulares of Phoenicia

In the fourth century, as a whole, almost 30 governors of Phoenicia are known with 23 governors of Phoenicia being in office between 353 and 394.[10]

| Date | Provincial governor (Consularis) |

|---|---|

| Between 293 and 305 | Aelius Statuus |

| Between 293 and 303 | Sossianus Hierocles |

| Before 305 | Julius Julianus |

| ? Between 309/313 | Maximus |

| c. 323 | Achillius |

| 328 – 329 | Fl. Dionysius |

| 335 | Archelaus |

| c. 337 | Nonnus |

| 342 | Marcellinus |

| 353/4 | Apollinaris |

| Before 358 | Demetrius |

| 358 – 359 | Nicentius[11] |

| (?) 359/60 | Euchrostius |

| Before 360 | Julianus |

| 360 – 361 | Andronicus |

| Before 361 | Aelius Claudius Dulcitius |

| 361 | Anatolius |

| c. 361/2 | Polycles |

| 362 | Julianus |

| 362 – 363 | Gaianus |

| 363 – 364 | Marius |

| 364 | Ulpianus |

| 364 – 365 | Domninus |

| 372 | Leontius |

| 380 | Petrus |

| 382 – 383 | Proculus |

| Before 388 | Eustathius |

| 388 | Antherius |

| 388 | Epiphanius |

| 390 | Domitius |

| 391 | Severianus |

| 392 | Leontius |

Notes

- Modern-day Homs/Hims (حمص), Syria.

- Arabic: تَدْمُر (Tadmur)

- A military unit of the Imperial Roman army

- Arabic: الرفنية, romanized: al-Rafaniyya; colloquial: Rafniye

- Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, a region in the ancient Maghreb.

References

- Eißfeldt 1941, p. 368.

- Ulpian, Digests 50.15.1.

- Herodian, Roman History 3.3.

- Eißfeldt 1941, pp. 368–369.

- Notitia Dignitatum, in partibus Orientis, I

- Eißfeldt 1941, p. 369.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 47–48, 240.

- Parker, “The Legions of Diocletian and Constantine,” p. 177/178.

- Hall, pg. 94

- A.H.M. Jones, J.R. Martindale, J. Morris, Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, vol. I: AD 260–395, Cambridge 1971 (hereinafter: PLRE I), pp. 1105–1110 (fasti). For the reviews, often negative, and corrections to the first volume of PLRE, cf. A.H.M. Jones, “Fifteen years of Late Roman Prosopography in the West” (1981–95), [in:] Medieval Prosopography 17/1, 1996, pp. 263–274.

- Martindale, J. R. & A. H. M. Jones, "Nicentius 1", The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I AD 260-395 (Cambridge: University Press, 1971), p. 628

Sources

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Eißfeldt, Otto (1941). "Phoiniker (Phoinike)". Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Vol. Band XX, Halbband 39, Philon–Pignus. pp. 350–379.

- Schürer Emil, Vermes Geza, Millar Fergus, The history of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.-A.D. 135), Volume I, Edinburgh 1973, p. 243-266 (Survey of the Roman Province of Syria from 63 B.C. to A.D. 70).

- Linda Jones Hall, Roman Berytus: Beirut in late antiquity (2004)

- Martindale, J. R.; Jones, A. H. M, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I AD 260–395, Cambridge University Press (1971)