History of Taiwan

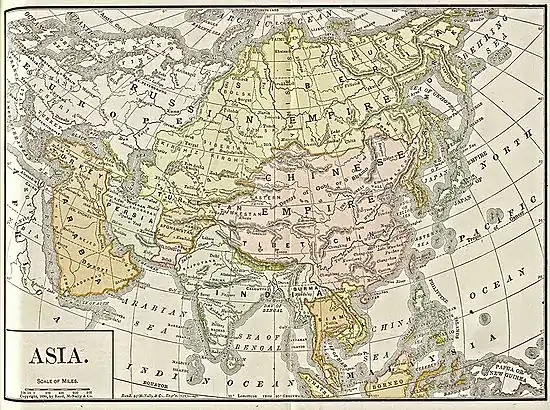

The history of the island of Taiwan dates back tens of thousands of years to the earliest known evidence of human habitation.[1][2] The sudden appearance of a culture based on agriculture around 3000 BC is believed to reflect the arrival of the ancestors of today's Taiwanese indigenous peoples.[3] Han Chinese gradually came into contact with Taiwan starting in the late 13th century and started settling there by the early 17th century. Named Formosa by Portuguese explorers, the south of the island was colonized by the Dutch in the 17th century whilst the Spanish built a settlement in the north which lasted until 1642. These European settlements were followed by an influx of Hoklo and Hakka immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong.

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| History of Taiwan | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣歷史 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Taiwanese history | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

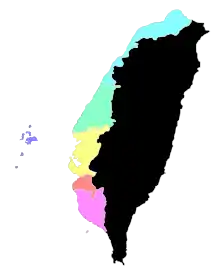

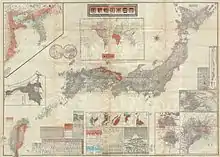

In 1662, Koxinga defeated the Dutch and established a base of operations on the island. His descendants were defeated by the Qing dynasty in 1683 and their territory in Taiwan was annexed by the Qing dynasty. Over two centuries of Qing rule, Taiwan's population increased by over two million and became majority Han Chinese due to illegal cross-strait migrations from mainland China and encroachment on Taiwanese indigenous territory. Due to the continued expansion of Chinese settlements, Qing-governed territory eventually encompassed the entire western plains and the northeast. The Qing ceded Taiwan and Penghu to Japan after losing the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Taiwan experienced industrial growth and became a productive rice- and sugar-exporting Japanese colony. During the Second Sino-Japanese War it served as a base for invasions of China, and later Southeast Asia and the Pacific during World War II.

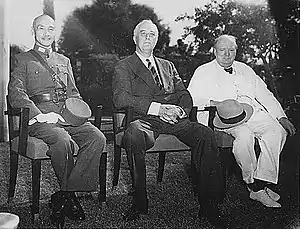

In 1945, following the end of hostilities in World War II, the nationalist government of the Republic of China (ROC), led by the Kuomintang (KMT), took control of Taiwan. The legality and nature of its control of Taiwan, including transfer of sovereignty, is debated.[4][5] In 1949, after losing control of mainland China in the Chinese Civil War, the ROC government under the KMT withdrew to Taiwan where Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law. The KMT ruled Taiwan (along with the islands of Kinmen, Wuqiu and the Matsu) as a single-party state for forty years until democratic reforms in the 1980s. The first-ever direct presidential election was held in 1996. During the post-war period, Taiwan experienced rapid industrialization and economic growth known as the "Taiwan Miracle", and was one of the "Four Asian Tigers".

Prehistory

In the Late Pleistocene, sea levels were about 140 metres (460 ft) lower than at present, exposing the floor of the shallow Taiwan Strait as a land bridge.[6] A concentration of vertebrate fossils has been found in the channel between the Penghu Islands and Taiwan, including a partial jawbone designated Penghu 1, apparently belonging to a previously unknown species of genus Homo, dated 450,000 to 190,000 years ago.[7] The oldest evidence of modern human presence on Taiwan consists of fragments and a tooth found at Chouqu and Gangzilin, in Zuojhen District, estimated to be between 20,000 and 30,000 years old.[1][8] The oldest artefacts are chipped-pebble tools of the Paleolithic Changbin culture found in Changbin, Taitung, dated 15,000 to 5,000 years ago. The same culture is found at sites at Eluanbi on the southern tip of Taiwan, persisting until 5,000 years ago.[2][9] Analysis of spores and pollen grains in sediment of Sun Moon Lake suggests that traces of slash-and-burn agriculture started in the area 11,000 years ago, and ended 4,200 years ago, when abundant remains of rice cultivation were found.[10] At the beginning of the Holocene 10,000 years ago, sea levels rose, forming the Taiwan Strait and cutting off the island from the Asian mainland.[6]

In 2011, the ~8,000-year-old Liangdao Man skeleton was found on Liang Island.[11][12] The only Paleolithic burial that has been found on Taiwan was in Chenggong in the southeast, dating from about 4000 BC.[13]

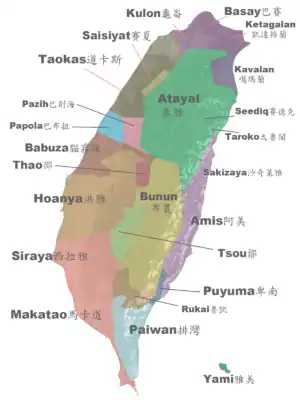

Around 3,000 BC, the Neolithic Dapenkeng culture abruptly appeared and quickly spread around the coast. Their sites are characterised by corded-ware pottery, polished stone adzes and slate points. The inhabitants cultivated rice and millet, but were also heavily reliant on marine shells and fish. Most scholars believe this culture is not derived from the Changbin culture, but was brought across the Strait by the ancestors of today's Taiwanese aborigines, speaking early Austronesian languages.[3][14] Some of these people later migrated from Taiwan to the islands of Southeast Asia and throughout the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Malayo-Polynesian languages are now spoken across a huge area, but form only one branch of the Austronesian family, the rest of whose branches are found only on Taiwan.[15][16][17][18] Trade links with the Philippine archipelago continued from the early 2nd millennium BC, including the use of jade from eastern Taiwan in the Philippine jade culture.[19]

The Dapenkeng culture was succeeded by a variety of cultures throughout the island, including the Tahu and Yingpu. Iron appeared in such cultures as the Niaosung Culture.[20] The earliest metal artifacts were trade goods, but by around 400 AD wrought iron was being produced locally using bloomeries, a technology possibly introduced from the Philippines.[21]

Chinese contact and settlement

Early Chinese histories refer to visits to eastern islands that some historians identify with Taiwan. Troops of the Three Kingdoms state of Eastern Wu are recorded visiting an island known as Yizhou in the spring of 230.[22] Some scholars have identified this island as Taiwan while others do not.[23] The Book of Sui relates that Emperor Yang of the Sui dynasty sent three expeditions to a place called "Liuqiu" early in the 7th century.[24] The Liuqiu described by the Book of Sui produced little iron, had no writing system, taxation, or penal code, and was ruled by a king. The natives used stone blades and practiced slash-and-burn agriculture.[22] Later the name Liuqiu (whose characters are read in Japanese as "Ryukyu") referred to the island chain to the northeast of Taiwan, but some scholars believe it may have referred to Taiwan in the Sui period.[25]

During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Han Chinese people started visiting Taiwan.[26] The Yuan emperor Kublai Khan sent officials to the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1292 to demand its loyalty, but the officials ended up in Taiwan and mistook it for Ryukyu. After three soldiers were killed, the delegation immediately retreated. Another expedition was sent in 1297. Wang Dayuan visited Taiwan in 1349 and mentioned the presence of Chuhou pottery from modern Lishui, suggesting that Chinese merchants had already visited the island.[27]

By the early 16th century, increasing numbers of Chinese fishermen, traders and pirates were visiting the southwestern part of the island. Some merchants from Fujian were familiar enough with the indigenous peoples of Taiwan to speak Formosan languages.[26] The people of Fujian sailed closer to Taiwan in the mid-16th century to trade with Japan while evading Ming authorities. Chinese who traded in Southeast Asia also began taking an East Sea Compass Course (dongyang zhenlu) that passed southwestern and southern Taiwan. Some of them traded with the Taiwanese aborigines. Taiwan was referred to as Xiaodong dao ("little eastern island") and Dahui guo ("the country of Dahui"), a corruption of Tayouan, a tribe that lived on an islet near modern Tainan from which the name "Taiwan" is derived. By the late 16th century, Chinese from Fujian were settling in southwestern Taiwan. In 1593, Ming officials started issuing licenses for Chinese junks to trade in northern Taiwan, acknowledging already existing illegal trade.[28]

Initially Chinese merchants arrived in northern Taiwan and sold iron and textiles to the aboriginal peoples in return for coal, sulfur, gold, and venison. Later the southwest became the primary destination for its mullet fish. Some fishing junks camped on Taiwan's shores and many began trading with the indigenous people for deer products. The southwestern Taiwanese trade was of minor importance until after 1567 when it was used as a way to circumvent the ban on Sino-Japanese trade. The Chinese bought deerskins from the aborigines and sold them to the Japanese for a large profit.[29]

Chen Di visited Taiwan in 1603 on an expedition against the Wokou pirates.[30][31] The pirates were defeated and they met a native chieftain who presented them with gifts.[32] Chen recorded these events in an account of Taiwan known as Dongfanji (An Account of the Eastern Barbarians) and described the natives of Taiwan and their lifestyle.[33]

When a Portuguese ship sailed past southwestern Taiwan in 1596, several of its crew members who had been shipwrecked there in 1582 noticed that the land had become cultivated, presumably by settlers from Fujian.[34] When the Dutch arrived in 1623, they found about 1,500 Chinese visitors and residents. A small minority brought Chinese plants with them and grew crops such as apples, oranges, bananas, watermelons.[35] Some estimates of the Chinese population put it at 2,000 over two villages, one of which would become Tainan. There was also a significant population of Chinese living in an aboriginal village where the villagers spoke a creole language incorporating many Chinese words.[26][29]

Dutch and Spanish colonies (1624–1668)

Contact and establishment

The name Formosa (福爾摩沙) dates from 1542, when Portuguese sailors noted it on their maps as Ilha Formosa (Portuguese for "beautiful island"). In 1582, the survivors of a Portuguese shipwreck spent 45 days battling malaria and aborigines before returning to Macau.[36][29]

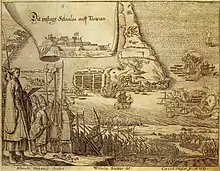

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) came to the area in search of an Asian trade and military base. Defeated by the Portuguese at the Battle of Macau in 1622, they attempted to occupy Penghu, but were driven off by the Ming authorities in 1624. They then built Fort Zeelandia on the islet of Tayowan off the southwest coast. On the adjacent mainland, they built a smaller brick fort, Fort Provintia.[37]

Piracy

The Europeans worked with and also fought against Chinese pirates. The pirate Li Dan mediated between Ming Chinese forces and the Dutch at Penghu. Chinese fishermen paid 10 percent of their catch to the pirates for a document guaranteeing their safety. The VOC to also enter the protection business; this was one of the first taxes levied on the colony. In July 1626, the Council of Formosa ordered all Chinese living or trading in Taiwan to obtain a residence permit.[38] This eventually became a head tax and major source of income for the Dutch.[38]

Zheng Zhilong became pirate chief in 1625 and pillaged under the Dutch flag, selling them the spoils. Chinese officials asked the Dutch for help against Zheng in return for trading rights. The Dutch failed and Zheng attacked the city of Xiamen. In 1628, Chinese authorities awarded him with an official title and imperial rank. Zheng became the "Patrolling Admiral" responsible for clearing the coast of pirates, and eliminated his competitors.[38] In the summer of 1633, a Dutch fleet and the pirate Liu Xiang carried out a successful sneak attack, destroying Zheng's fleet.[38] On 22 October 1633, Zheng forces lured the Dutch fleet and their pirate allies into an ambush and defeated them.[39][40] The Dutch reconciled with Zheng and he arranged for more Chinese trade in Taiwan. In 1637, Liu was defeated by Zheng.[38]

Japanese trade

The Japanese had been trading for Chinese products in Taiwan since before the Dutch arrived in 1624. In 1609, the Tokugawa shogunate sent an exploratory mission to the island.[41] In 1616, Murayama Tōan sent 13 vessels to conquer Taiwan. The fleet was dispersed by a typhoon.[42][43]

In 1625, Batavia ordered the governor of Taiwan to prevent the Japanese from trading because they paid more for silk. The Dutch also restricted Japanese trade with the Ming dynasty.[38] The loss of Japanese trade made trade in Taiwan far less profitable. After 1635, the shogun forbade Japanese from going abroad and eliminated the Japanese threat to the company. The VOC expanded into previous Japanese markets in Southeast Asia.[38]

Spanish Formosa

In 1626, the Spanish Empire, viewing the Dutch presence on Taiwan as a threat to their colony in the Philippines, established a settlement at Santísima Trinidad on the northeast coast (modern Keelung), building Fort San Salvador. They also built Fort Santo Domingo in the northwest (modern Tamsui) in 1629 but abandoned it by 1638 due to conflicts with the local population. The small colony was plagued by disease, faced hostile locals, and received little support from Manila, who viewed the fortresses as a drain on their resources.[44]

In August 1641, the Dutch and their native allies tried to take the Spanish fortresses but they did not have enough artillery.[45] In August 1642, the Dutch ejected the Spanish.[46][47]

Dutch colonization

According to Salvador Diaz, initially there were only 320 Dutch soldiers and they were "short, miserable, and very dirty."[38] Dutch ships wrecked at Liuqiu in 1624 and 1631; their crews were killed by the inhabitants.[48] In 1633, an expedition consisting of 250 Dutch soldiers, 40 Chinese pirates, and 250 Taiwanese natives were sent against Liuqiu Island but met with little success.[49]

The Dutch allied with Sinkan, a small village that provided them with firewood, venison and fish.[50] In 1625, they bought land from the Sinkanders and built the town of Sakam for Dutch and Chinese merchants.[51] Initially the other villages maintained peace with the Dutch. In 1625, the Dutch attacked 170 Chinese pirates in Wankan but were driven off. Encouraged by the Dutch failure, Mattau warriors raided Sinkan. The Dutch returned and drove off the pirates. The people of Sinkan then attacked Mattau and Baccluan, and sought protection from Japan. In 1629, Pieter Nuyts visited Sinkan with 60 musketeers. After Nuyts left, the musketeers were killed in an ambush by Mattau and Soulang warriors.[38] On 23 November 1629, an expedition set out and burned most of Baccluan, killing many of its people, who the Dutch believed harbored proponents of the previous massacre. Baccluan, Mattau, and Soulang people continued to harass company employees until late 1633 when Mattau and Soulang went to war with each other.[38]

In 1635, 475 soldiers from Batavia arrived in Taiwan.[52] By this point even Sinkan was on bad terms with the Dutch. Soldiers were sent into the village and arrested those who plotted rebellion. In the winter of 1635 the Dutch defeated Mattau and Baccluan. In 1636, a large expedition was sent against Liuqiu Island. The Dutch and their allies chased about 300 inhabitants into caves, sealed the entrances, and killed them with poisonous fumes. The native population of 1100 was removed from the island.[53] They were enslaved with the men sent to Batavia while the women and children became servants and wives for the Dutch officers. The Dutch planned to depopulate the outlying islands.[54] The villages of Taccariang, Soulang, and Tevorang were also pacified.[38] In 1642, the Dutch massacred the people of Liuqiu island again.[55]

The Dutch estimated in 1650 that there were around 50,000 natives in the western plains region;[56] the Dutch Formosa ruled around "315 tribal villages with a total population of around 68,600, estimated 40–50% of the entire indigenes of the island".[57] The Dutch tried to convince the natives to give up hunting and adopt sedentary farming but their efforts were unsuccessful.[58] The VOC administered the island and its predominantly aboriginal population until 1662. They set up a tax system and schools to teach romanized script of Formosan languages and evangelize Christianity.[59][53] They tried to teach the native children the Dutch language but the effort was abandoned after failing to produce good results.[60] The native Taiwanese religion was primarily animist. Practices like mandatory abortion, marital infidelity, nakedness, and non-observation of the Christian Sabbath were considered sinful. The Bible was translated into the native languages. This was the first entrance of Christianity into Taiwan.[57]

The Dutch levied a tax on all imports and exports. A tax was also levied on every non-Dutch person above the age of six. This poll tax was highly unpopular and the cause the major insurrections in 1640 and 1652. A tax was imposed on hunting through licenses for pit-traps and snaring.[61][62] Although its control was mainly limited to the western plain of the island, the Dutch systems were adopted by succeeding occupiers.[63] The Dutch originally sought to use their castle Zeelandia at Tayowan as a trading base between Japan and China, but soon realized the potential of the huge deer populations that roamed Taiwan's western regions.[56]

Chinese settlers

The VOC encouraged Chinese migration to Taiwan and provided a military and administrative structure for Chinese immigration. It advertised to the Chinese a number of economic benefits and even paid them to move to Taiwan. Thousands of Chinese, mostly young single men, became rice and sugar planters.[64][26]

In 1625, the company started advertising Provintia as a site of settlement. The next year the town caught fire and both the Chinese and company personnel left. In 1629, the natives of Mattau and Soulang attacked Sakam and chased away the inhabitants of Provintia. In 1632, the company encouraged the Chinese to plant sugarcane in Sakam.[26] In the spring of 1635, 300 Chinese laborers arrived. The Chinese initially cultivated rice but lost interest in the crop by 1639 due to lack of access to water. This was addressed in the early 1640s and rice production resumed. Various industries sprung up and in the 1640s the Dutch began to tax them, causing some discontent.[26] After 1648, nearly all company revenue came from the Chinese.[65]

The Chinese were allowed to own property in a limited area. The Dutch attempted to prevent the Chinese from mingling with the natives.[26] The natives traded meat and hides for salt, iron, and clothing from Chinese traders. In 1634 the Dutch ordered the Chinese to sell deerskins to only the company. By 1636, Chinese hunters were entering previously native lands cleared by the Dutch. Commercial hunters replaced the natives and by 1638 the future of the deer population was in question. Restrictions on hunting were implemented.[66]

In 1636, Favorolang, the largest aboriginal village north of Mattau, killed three Chinese and wounded several others. From August to November, Favrolangers appeared near Fort Zeelandia and captured a Chinese fishing vessel. The next year the Dutch and their native allies defeated Favorolang. The expedition was paid for by the Chinese populace. When peace negotiations failed, the Dutch blamed a group of Chinese at Favorolang. The Favorolangers continued their attacks until 1638. In 1640 an incident involving the capture of a Favorolang leader and the ensuing death of three Dutch hunters near Favorolang resulted in the banning of Chinese hunters from Favorolang territory. The Dutch blamed the Chinese and orders were given to restrict Chinese residency and travel. No Chinese vessel was allowed around Taiwan unless it carried a license. An expedition was ordered to chase away the Chinese from the land and to subjugate the natives to the north. In November 1642, an expedition set out northward, killing 19 natives and 11 Chinese. A policy banning any Chinese from living north of Mattau was implemented. Later the Chinese were allowed to conduct trade in Favorolang with a permit. The Favorolangers were told to capture any Chinese who did not possess a permit.[66]

In the late 1630s, Batavia started pressuring the authority in Taiwan to increase revenues. The Dutch started collecting voluntary donations from the Chinese. In addition to a 10 percent tax on numerous products and real estate sales, they also implemented a residency-permit tax. Chinese settlers began protesting the residency tax, that the Dutch harassed them for pay.[67] The Dutch thought the Chinese were exploiting the natives by selling at high prices.[67] The sale of rights to trade with aborigines was not just a way to raise profits but to keep track of the Chinese and prevent them from mingling with the natives.[67]

On 8 September 1652, a Chinese farmer, Guo Huaiyi, and an army of peasants attacked Sakam. Most of the Dutch were able to find refuge but others were captured and executed. Over the next two days, natives and Dutch killed around 500 Chinese. On 11 September, four or five thousand Chinese rebels clashed with the company soldiers and their native allies. The rebels fled; some 4,000 Chinese were killed.[67] The rebellion and its ensuing massacre destroyed the rural labor force. Although the crops survived almost unscathed, there was a below average harvest for 1653. However thousands of Chinese migrated to Taiwan due to war on the mainland and a modest recovery of agriculture occurred. Anti-Chinese measures increased. Natives were reminded to watch the Chinese and not to engage with them. However in terms of military preparations, little was done.[65] In May 1654, Fort Zeelandia was afflicted by locusts, a plague, and an earthquake.[68]

End of Dutch rule

Zheng Chenggong, known in Dutch sources as Koxinga, studied at the Imperial Academy in Nanjing. When Beijing fell in 1644 to rebels, Chenggong and his followers declared their loyalty to the Ming dynasty and he was bestowed the title Guoxingye (Lord of the Imperial surname). Chenggong continued the resistance against the Qing from Xiamen. In 1650 he planned a major offensive from Guangdong. The Qing deployed a large army to the area and Chenggong decided to ferry his army along the coast but a storm hindered his movements. The Qing launched a surprise attack on Xiamen, forcing him to return to protect it. From 1656 to 1658 he planned to take Nanjing. Chenggong encircled Nanjing on 24 August 1659. Qing reinforcements arrived and broke Chenggong's army, forcing them to retreat to Xiamen. In 1660 the Qing embarked on a coastal evacuation policy to starve Chenggong of his source of livelihood.[68] Some of the rebels during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion had expected aid from Chenggong and some company officials believed that the rebellion had been incited by him.[68]

In the spring of 1655 no silk junks arrived in Taiwan. Some company officials suspected that this was a plan by Chenggong to harm them. In 1655, the governor of Taiwan received a letter from Chenggong referring to the Chinese in Taiwan as his subjects. He commanded them to stop trading with the Spanish. Chenggong directly addressed the Chinese leaders in Taiwan rather than Dutch authorities, stating that he would withhold his junks from trading in Taiwan if the Dutch would not guarantee their safety. Chenggong had increased foreign trade by sending junks to various regions and Batavia was wary of this competition. Batavia sent a small fleet to Southeast Asian ports to intercept Chenggong's junks. One junk was captured but another junk managed to escape.[68] The Taiwanese trade slowed and for several months in late 1655 and early 1656 not a single Chinese vessel arrived in Tayouan. Even low-cost goods grew scarce and the value of aboriginal products fell. The system of selling Chinese merchants the right to trade in aboriginal villages fell apart. On 9 July 1656, a junk flying Chenggong's flag arrived at Fort Zeelandia. Chenggong wrote that he was angry with the Dutch but since Chinese people lived in Taiwan, he would allow them to trade on the Chinese coast for 100 days so long as only Taiwanese products were sold. Chinese merchants began leaving. Chenggong confiscated a Chinese junk from Tayouan trading pepper in Xiamen, causing Chinese merchants to abort their trade voyages. Chinese merchants refused to buy the company's foreign wares and even sold their own foreign wares, causing prices to collapse.[68]

Chinese merchants in aboriginal villages ran out of goods to trade for aboriginal products. Chinese farmers also suffered due to the exodus of Chinese. By the end of 1656, Chinese farmers were asking for relief from debts and many could barely find food for themselves.[68]

Chenggong retreated from his stronghold in Amoy (Xiamen city) and attacked the Dutch colony in Taiwan in the hope of establishing a strategic base to marshal his troops to retake his base at Amoy. On 23 March 1661, Zheng's fleet set sail from Kinmen with a fleet carrying around 25,000 soldiers and sailors. The fleet arrived at Tayouan on 2 April. Zheng's forces routed 240 Dutch soldiers at Baxemboy Island in the Bay of Taiwan and landed at the bay of Luermen.[69][70] Three Dutch ships attacked the Chinese junks and destroyed several until their main warship exploded. The remaining ships were unable to keep Zheng from controlling the waters around Taiwan.[71][72]

On 4 April, Fort Provintia surrendered to Zheng's forces. Following a nine-month siege, Chenggong captured the Dutch fortress Zeelandia and established a base in Taiwan.[73] The Dutch held out at Keelung until 1668 when they withdrew from Taiwan completely.[74][75][76]

Kingdom of Tungning (1661–1683)

Conquest

Koxinga renamed Zeelandia to Anping and Provintia to Chikan.[77] On 29 May 1662, Chikan was renamed to "Ming Eastern Capital" (Dongdu Mingjing). Later "Eastern Capital" (Dongdu) was renamed Dongning (Wades Giles: Tungning), which means "Eastern Pacification,"[78] by Zheng Jing, Koxinga's son. One prefecture and two counties (Tianxing and Wannian) were established in Taiwan.[77]

Koxinga died on 23 June 1662. Chinese nationalists in the 20th century invoked Koxinga for his patriotism and political loyalty against Qing and foreign influence.[79][80][81][82]

Retreat to Taiwan

Zheng Jing's succession was contested by Zheng Miao, Zheng Chenggong's fifth son. Zheng Jing arrived in Taiwan in December 1662 and defeated his enemies. The infighting caused some followers to defect to the Qing. By 1663, some 3,985 officials and officers, 40,962 soldiers, 64,230 civilians, and 900 ships in Fujian had defected from Zheng territory.[83] To combat population decline, Zheng Jing promoted migration to Taiwan. Between 1665 and 1669 a large number of Fujianese moved to Taiwan. Some 9,000 Chinese were brought to Taiwan by Zheng Jing.[84]

The Qing dynasty enacted a sea-ban to starve out the Zheng forces. In 1663, the writer Xia Lin testified that the Zhengs were short on supplies and the people suffered tremendous hardship.[85] The Dutch attacked Zheng ships in Xiamen but failed to take the town. The Dutch assisted the Qing in combat against the Zheng fleet in October 1663, resulting in the capture of Zheng bases in Xiamen and Kinmen. The remaining Zheng forces fled southward and completely evacuated from the mainland coast in the spring of 1664.[86] Qing-Dutch forces attempted to invade Taiwan twice in December 1664 and again in 1666 but were impacted by adverse weather. The Dutch continued to attack Zheng ships occasionally but were unable to take back the island.[87][88]

After Zheng Jing was ejected from the mainland, the Qing tried to settle the conflict through negotiation.[89] In 1669 the Qing offered Zheng significant autonomy in Taiwan if they shaved their heads in the Manchu style. Zheng Jing declined and insisted on a relationship with the Qing similar to Korea.[90] In 1670 and 1673, Zheng forces seized vessels on their way to the mainland. In 1671, Zheng forces raided the coast of Zhejiang and Fujian. In 1674, Zheng Jing joined the Revolt of the Three Feudatories and recaptured Xiamen. He imported war material and made an alliance with Geng Jingzhong in Fujian. They fell afoul of each other not long afterward. Zheng captured Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in 1674. After Geng and other rebels surrendered to the Qing in 1676 and 1677, the tide turned against the Zheng forces. Quanzhou was lost to the Qing on 12 March 1677 and then Zhangzhou and Haicheng on 5 April. Zheng forces counterattacked and retook Haicheng in August. Zheng naval forces blockaded Quanzhou and tried to retake the city in August 1678 but they were forced to retreat when Qing reinforcements arrived. Zheng forces suffered heavy casualties in a battle in January 1679.[91] On 20 March 1680, the Qing fleet led by Wan Zhengse defeated Zheng naval forces near Quanzhou. Many Zheng commanders and soldiers defected to the Qing. Xiamen was abandoned. On 10 April, Zheng Jing's war on the mainland came to a close.[92] Zheng Jing died in early 1681.[93]

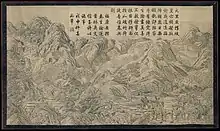

Sinicization

Zheng Jing never relinquished the trappings of a Ming government,[94] enabling him to draw support from Ming loyalists. In Taiwan, the Six Ministries were established, however oversight of all affairs was given to military leaders. Zheng's family and officers remained at the top of the administration.[95] They enacted programs of agricultural and infrastructural development. By 1666, grain harvests were more than capable of sustaining the population.[96] Zheng also advised commoners to improve their dwellings and for temples dedicated to the Buddha and local Fujianese deities to be constructed. An Imperial Academy and Confucian Shrine were established in 1665 and 1666 while regular civil service examinations were implemented.[78]

Zheng dispatched teachers to aboriginal tribes to provide them with supplies and teach them more advanced farming techniques.[97] Schools were set up to teach the aboriginal people the Chinese language and those who refused were punished.[98][97] The expansion of Chinese settlements often came at the expense of aboriginal tribes, causing rebellions flared up over the course of Zheng rule. In one campaign, several hundred Shalu tribes people in modern Taichung were killed.[97][99] The Chinese population in Taiwan more than doubled under Zheng rule.[100] Zheng disbanded the troops and turned them into military colonies.[101]

By the start of 1684, a year after the end of Zheng rule, areas under cultivation in Taiwan had tripled in size since the end of the Dutch era in 1660.[99] Zheng merchant fleets continued to operate between Japan and Southeast Asian countries, reaping profits as a center of trade. They extracted a tax from traders for safe passage through the Taiwan Strait. Zheng Taiwan held a monopoly on certain commodities such as deer skin and sugarcane, which sold at a high price in Japan.[102] Zheng Taiwan achieved greater economic diversification than the profit-driven Dutch colony and cultivated more types of grain, vegetables, fruits, and seafood. By the end of Zheng rule in 1683, the government was extracting over 30% more annual income in silver than under the Dutch in 1655. Sugar exports exceeded Dutch figures in 1658 while deerskin output remained the same.[103]

Shi Lang

.jpg.webp)

Shi Lang led the Qing conquest of Zheng Taiwan. He was originally a military leader working under Zheng Zhilong, the father of Zheng Chenggong. He had a falling out with Chenggong. After escaping imprisonment by Chenggong, Shi Lang defected to the Qing dynasty and participated in a successful assault on a Zheng stronghold. In 1658, Shi was made Deputy Commander of Tongan and continued to participate in campaigns against Zheng forces. Shi relayed information about Zheng internal conflict between Chenggong and his son to Beijing.[104] The Qing established a naval force in Fujian in 1662 and appointed Shi Lang as the commander. Shi advocated for more aggressive action against the Zhengs. On 15 May 1663, Shi attacked the Zheng fleet and succeeded in killing and capturing Zheng forces. From 18 to 20 November, the Dutch fought sea battles against Zheng forces while Shi took Xiamen. In 1664, Shi assembled a fleet of 240 ships, and in conjunction with 16,500 troops, chased remaining Zheng forces south. They failed to dislodge the last Zheng stronghold. After the defection of Zheng commander Zhou Quanbin, Zheng Jing pulled out from the remaining mainland stronghold in the spring of 1664.[105]

End of Zheng rule

Shi Lang was instructed to arrange a peace mission to Taiwan but he did not believe Zheng Jing would accept the terms. He warned that if the Zhengs built up their strength, they would pose a serious danger. Shi detailed his plans to invade Taiwan; he argued that securing Taiwan would render garrisons unnecessary and reduce the defense spending.[106] In 1681, Li Guangdi recommended Shi Lang to be the coordinator of the invasion force. Shi was reappointed as naval chief of Fujian on 10 September 1681.[107] Shi's plan was to take Penghu first. The Governor-general Yao Qisheng disagreed and proposed a two pronged attack on Tamsui and Penghu at the same time. Shi thought the proposal was unrealistic and requested to be put in total control over the entire invasion force. Kangxi denied the request.[108]

In Taiwan, Zheng Jing's death resulted in a coup. Zheng Keshuang murdered his brother Zheng Kezang. Political turmoil, heavy taxes, an epidemic in the north, a large fire that caused the destruction of more than a thousand houses, and suspicion of collusion with the Qing caused more Zheng followers to defect to the Qing. Zheng's deputy Commander Liu Bingzhong surrendered with his ships and men from Penghu.[109] Orders from the Kangxi Emperor to invade Taiwan reached Yao Qisheng and Shi Lang on 6 June 1682. The invasion fleet met with unfavorable winds and was forced to turn back. Conflict between Yao and Shi led to Yao's removal in November.[110] On 18 November 1682, Shi Lang was authorized to assume the role of supreme commander and Yao was relegated to logistics. Two attempts to sail to Penghu in February 1683 failed due to a shift in winds.[111]

Shi's fleet of 238 ships and over 21,000 men set sail on 8 July 1683.The next day, Shi's fleet approached small islands to the northwest of Penghu. The Qing forces were met by 200 Zheng ships. Following an exchange of gunfire, the Qing were forced to retreat with Zheng forces in pursuit. The Qing vanguard led by Lan Li provided cover fire for a withdrawal. The Zheng side also suffered heavy losses, making Liu reluctant to pursue the disarrayed Qing forces.[112] On 11 July, Shi regrouped his squadrons and requested reinforcements at Bazhao. On 16 July, reinforcements arrived. Shi divided the main striking force into eight squadrons of seven ships with himself leading from the middle. Two flotillas of 50 small ships sailed in different directions as a diversion. The remaining vessels served as rear reinforcements.[113]

The battle took place in the bay of Magong. The Zheng garrison fired at the Qing ships and then set sail from the harbor with about 100 ships to meet the Qing forces. Shi concentrated fire on one big enemy ship at a time until all of Zheng's battle ships were sunk by the end of 17 July. Approximately 12,000 Zheng forces perished. Liu escaped to Taiwan while the garrison commanders surrendered. The Qing captured Penghu on 18 July.[114] Shi Lang arrived in Taiwan on 5 October 1683 to supervise the surrender, which went smoothly. Zheng Keshuang and other leaders shaved their head in the Manchu style. The use of the Ming calendar in Taiwan was ended.[115]

Qing dynasty (1683–1895)

Annexation

Shi Lang remained in Taiwan for 98 days before returning to Fujian on 29 December 1683. In Fujian, some officials from the central government advocated for transporting all of Taiwan's inhabitants to the mainland and abandoning the island.[116] One argued that defending Taiwan was impossible and increasing defense expenditures was unfavorable.[116]

Shi opposed abandoning Taiwan, arguing that this would leave it open to other enemies. He assured that defending Taiwan would only take 10,000 men and reduce garrison forces on the coast. Shi convinced all the attendees at the Fujian conference, with the exception of Subai, that it was in their best interests to annex Taiwan.[117] On 6 March 1684, Kangxi accepted Shi's proposal to set up permanent military establishments in Penghu and Taiwan and authorized the establishment of Taiwan Prefecture, divided into three counties, as a prefecture of Fujian Province.[118][119]

Taiwan administration

The Qing initially forbade mainlanders from moving to Taiwan and sent most of the people back to the mainland, after which the official population of Taiwan was only 50,000. Manpower shortage compelled local officials to solicit migrants from the mainland despite restrictions. Sometimes even warships transported civilians to Taiwan.[120] By 1711, illegal migrants amounted to tens of thousands yearly.[121] Individuals such as Lin Qianguang, a native of Fujian Province, entered Taiwan. He held office in Taiwan from 1687 to 1691 but lived in Taiwan for several years beforehand. He wrote one of the first accounts of aboriginal life i Taiwan in 1685.[122]

The first recorded regulation on the permit system was made in 1712 but it probably existed as early as 1684. Its purpose was to reduce population pressure on Taiwan. The government believed that Taiwan was unable to support a larger population before leading to conflict. Regulations banned migrants from bringing their families. To prevent undesirables from entering Taiwan, the government recommended only allowing those who had property or relatives in Taiwan to enter Taiwan. A regulation to this effect was implemented in 1730.[123]

Over the 18th century, regulations on migration remained largely consistent. Early regulations focused on the character of permit receivers while later regulations reiterated measures such as patrolling and punishment. The only changes were to the status of families.[123] Families were barred from entering Taiwan to ensure that migrants would return to their families. The overwhelmingly male migrants had few prospects and thus married locally, resulting in the idiom "has Tangshan[lower-alpha 1] father, no Tangshan mother" (Chinese: 有唐山公,無唐山媽; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ū Tn̂g-soaⁿ kong, bô Tn̂g-soaⁿ má).[124][125] Marrying aboriginal women was prohibited in 1737 on the grounds that it interfered in aboriginal life and was used as a means to claim aboriginal land.[126][127]

Migrant families were allowed to enter Taiwan legally for a period between 1732 and 1740. In 1739, opposition to family migrations claimed that vagrants and undesirables were taking advantage of the system. Families were barred again from 1740 to 1746. In 1760, family crossings to Taiwan became legal again for a short period. Starting in 1771, Qing restrictions on cross-strait migration relaxed as they realized that the policies were unenforceable. Even during periods of legal migration, more individuals chose to hire illegal ferry service than to deal with official procedures. After lifting restrictions on family crossings in 1760, only 277 people requested permits after a year, the majority of them being government employees. In comparison, within a ten-month period in 1758–1759, nearly 60,000 people were arrested for illegal crossings. In 1790, an office was set up to manage civilian travel between Taiwan and the mainland, and the Qing government ceased to actively interfere in cross-strait migration.[121][128][127] In 1875, all restrictions on entering Taiwan were repealed.[121]

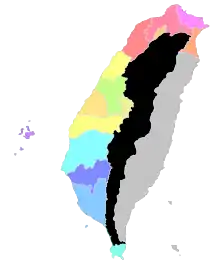

Settler expansion (1684–1795)

From 1661 to 1796, the Qing restricted expansion of territory in Taiwan. Taiwan was garrisoned with 8,000 soldiers at key ports and civil administration was kept to a minimum. Three prefectures nominally covered the entire western plains but effective administration covered a smaller area. A permit was required for settlers to go beyond the mid-point of the western plains. In 1715, the governor-general of Fujian-Zhejiang recommended land reclamation in Taiwan but the Kangxi Emperor was worried that this would cause instability and conflicts.[131]

Under the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722–1735), the Qing extended control over the entire western plains to better control settlers and maintain security. This was not an active colonization policy but a reflection of continued illegal crossings and land reclamation. After the Zhu Yigui uprising in 1721, Lan Dingyuan, an advisor to Lan Tingzhen, who led forces against the rebellion, advocated for land reclamation to strengthen government control over Chinese settlers and to incorporate aboriginals under their administration.[132]

Under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), the administrative structure of Taiwan remained largely unchanged. After the Lin Shuangwen rebellion in 1786, Qianlong agreed that leaving fertile lands to unproductive aborigines only attracted illegal settlers.[133] The Qing did little to administer the aborigines and rarely tried to impose control over them. Aborigines were classified into two categories: acculturated aborigines (shufan) and non-acculturated aborigines (shengfan). To the Qing, shufan were aborigines who paid taxes and had adopted Han Chinese culture. When the Qing annexed Taiwan, there were 46 aboriginal villages under government control, likely inherited from the Zheng regime. In the Yongzheng period, 108 aboriginal villages submitted as a result of enticement from the regional commander, Lin Liang. Shengfan who paid taxes but did not practice Han Chinese culture were called guihua shengfan (submitted non-acculturated aborigines).[134]

The Qianlong administration forbade enticing aborigines to submit due to fear of conflict. In the early Qianlong period, there were 299 named aboriginal villages. Records show 93 shufan villages and 61 guihua shengfan villages. The number of shufan villages remained stable throughout the Qianlong period. Two aboriginal affairs sub-prefects were appointed to manage aboriginal affairs in 1766. One in charge of the north and the other in charge of the south. Boundaries were built to keep the mountain aborigines out of settlement areas. The policy of marking settler boundaries and segregating them from aboriginal territories became official policy in 1722. Fifty-four stelae were used to mark crucial points along the boundary. Settlers were forbidden from crossing into aboriginal territory but settler encroachment continued, and the boundaries were rebuilt in 1750, 1760, 1784, and 1790. Settlers were forbidden from marrying aborigines as marriage was one way to obtain land.[128]

| Taiwan Population Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Chinese | Aboriginal | Total |

| 1623 | 1,500[26] | ||

| 1652 | 25,000[67] | ||

| 1654 | 100,000[135] | ||

| 1661 | 35,000[136] | ||

| 1664 | 50,000[137] | ||

| 1683 | 120,000[138] | ||

| 1756 | 660,147[139] | ||

| 1777 | 839,803[140] | ||

| 1782 | 912,000[141] | ||

| 1790 | 950,000[142] | ||

| 1811 | 1,944,747[143] | ||

| 1824 | 1,786,883[141] | ||

| 1893 | 2,545,000[144] | ||

| 1905 | 2,492,784[137] | 82,795[137] | 3,039,751[137] |

| 1915 | 3,325,755[145] | ||

| 1925 | 3,993,408[137] | ||

| 1935 | 5,212,426[137] | ||

| 1945 | 6,560,000[137] | ||

| 1955 | 9,078,000[137] | ||

| 1958 | 10,000,000[146] | ||

| 1965 | 12,628,000[137] | ||

| 1975 | 16,150,000[137] | ||

| 1985 | 19,258,000[137] | ||

| 1995 | 21,300,000[137] | ||

| 2015 | 546,700[147] | ||

| 2018 | 23,550,000[148] |

Administrative expansion (1796–1874)

Qing quarantine policies were maintained in the early 19th century but attitudes towards aboriginal territory shifted. Local officials repeatedly advocated for colonization, especially in the cases of Gamalan and Shuishalian in modern Yilan County in northeastern Taiwan. The Kavalan people had started paying taxes as early as the Kangxi period (r. 1661–1722), but they were non-acculturated aborigines.[149]

In 1787, a Chinese settler named Wu Sha tried to colonize Gamalan but was defeated. The next year, the Taiwan prefect, Yang Tingli, was convinced to support Wu Sha. Yang recommended colonization of Gamalan to the Fujian governor but the governor refused. In 1797, a new Tamsui sub-prefect supported Wu in his colonization efforts despite the ban. Wu's successors were unable to register their land on government registers. Local officials could not officially recognize it.[150]

In 1806 a pirate, Cai Qian, was within the vicinity of Gamalan. Taiwan Prefect Yang argued that abandoning Gamalan would cause trouble on the frontier. Later another pirate band tried to occupy Gamalan. Yang recommended establishing administration and land surveys in Gamalan. In 1809, the emperor ordered for Gamalan to be incorporated. An imperial decree for the formal incorporation of Gamalan was issued and a Gamalan sub-prefect was appointed.[151]

Unlike Gamalan, debates on Shuishalian (upstream areas of the Zhuoshui River and Wu River) resulted in its continued status as a forbidden area. Six aboriginal villages occupied the flat and fertile basin area of Shuishalian. The aboriginals had submitted as early as 1693 but they remained non-acculturated. In 1814, some settlers obtained reclamation permits through fabricating land lease requests. In 1816, government troops evicted the settlers.[152] Multiple officials recommended opening up Shuishalian between 1823 and 1848, but these recommendations were ignored.[153] The subject of land reclamation continued to be a topic of discussion and the Tamsui subprefecture gazetteer in 1871 openly called for colonization.[154]

Expansion in reaction to crises (1875–1895)

In 1874, Japan invaded southern Taiwan in what is known as the Mudan Incident (Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1874)). For six months Japanese soldiers occupied southern Taiwan until the Qinga paid an indemnity in return for their withdrawal.[156]

The imperial commissioner for Taiwan, Shen Baozhen, recommended subjugating the aborigines and populating their territory with Chinese settlers to prevent Japanese encroachment. The administration of Taiwan was expanded and campaigns against the aborigines were launched. Starting in 1874, mountain roads were built and aborigines were brought into formal submission. In 1875, the ban on entering Taiwan was lifted.[157] In 1877, 21 guidelines on subjugating aborigines and opening the mountains were issued. Agencies for recruiting settlers were established. Efforts to promote settlement in Taiwan petered out soon after.[158]

The Sino-French War broke on in 1883 and the French occupied Keelung in northern Taiwan in 1884. The French army withdrew in 1885. Efforts to colonize aboriginal territory were renewed under Liu Mingchuan, the Taiwan defense commissioner. In 1887, Taiwan became its own province. During Liu's tenure, Taiwan's capital was shifted to modern Taichung. Taipei was built up as a temporary capital and then became the permanent capital in 1893. Liu's efforts to increase revenues were mixed due to foreign pressure to reduce levies. A cadastral reform survey was undertaken from June 1886 to January 1890 that met with opposition in the south. The receipts from the land tax reform fell short of expectations.[159]

Electric lighting, modern weaponry, a railway, cable and telegraph lines, a local steamship service, and industrial machinery were introduced to Taiwan. A telegraph line from Tainan to Tamsui was constructed in 1886–88 and a railway connecting Keelung, Taipei, and Hsinchu was built. These efforts met with mixed results. The telegraph line only functioned in bursts of a week due to a difficult overland connection and the railway required an overhaul, serviced small rolling stock, and carried little freight.[160] Taiwan attracted few laborers and few settlers went to Taiwan due to the aborigines and harsh climate. Governor Liu was criticized for the high cost and little gain of colonization activities. Liu resigned in 1891 and the colonization efforts ceased.[161]

A Taiwan Pacification and Reclamation Head Office was established. By 1887, roughly 90,000 aborigines had formally submitted to Qing rule. This number increased to 148,479 aborigines over the following years. However the cost of getting them to submit was exorbitant. The Qing offered them materials and paid village chiefs monthly allowances. Not all the aborigines were under effective control and land reclamation in eastern Taiwan occurred at a slow pace.[161] From 1884 to 1891, Liu launched more than 40 military campaigns against the aborigines with 17,500 soldiers. A third of the invasion force was killed or disabled in the conflict.[160]

By the end of the Qing period, the western plains were developed farmland areas with about 2.5 million Chinese inhabitants. The mountainous areas were still largely autonomous and aboriginal land loss occurred at a relatively slow pace.[162][144] However by the last years of Qing rule, most of the plains aborigines had been acculturated to Han culture, around 20–30% could speak their mother tongues, and they gradually lost their land ownership and rent collection rights.[163]

Rebellions

.jpg.webp)

In 1723, aborigines along the central coastal plain rebelled. Troops from southern Taiwan were sent to put down this revolt, but in their absence, Han settlers in Fengshan County rose up in revolt.[164] By 1732, five different ethnic groups were in revolt but the rebellion was defeated by the end of the year.[164] During the Qianlong period (1735–1796), the 93 shufan acculturated aborigine villages never rebelled and over 200 non-acculturated aboriginal villages submitted.[165] During the 200 years of Qing rule in Taiwan, the plains aborigines rarely rebelled against the government and the mountain aborigines were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule. Most rebellions were caused by Han settlers.[166]

In 1720, there was an upset among in Taiwan due to increased taxation. They gathered around Zhu Yigui and supported him in an anti-Qing rebellion.[167][168] Hakka leader Lin Junying from the south also joined the rebellion. In March 1720, Zhu and Lin attacked Taiwan County. In less than two weeks, the rebels had defeated Qing forces across Taiwan. The Hakka troops left Zhu to follow Lin north. The Qing sent a fleet under the command of Shi Shibian; the rebellion was defeated and Zhu was executed.[167]

In 1786, members of the Tiandihui society were arrested for failing to make tax payments. The Tiandihui broke into the jail and rescued their members. When Qing troops were sent to arrest Lin Shuangwen, the leader of the Tiandihui led his forces to defeat the Qing troops.[169] Many of the rebel army's troops came from new arrivals from mainland China who could not find land.[168] Lin attacked Changhua County, killing 2,000 civilians. In early 1787, 50,000 Qing troops under Li Shiyao were sent to put down the rebellion. Lin tried to enlist the support of the Hakka people but they sent their troops to support the Qing.[169] Despite the Tiandihui's ostensibly anti-Qing stance, its members were generally anti-government and were not motivated by ethnic or national interest, resulting in social discord.[168] In 1788, 10,000 Qing troops led by Fuk'anggan and Hailanqa were sent to Taiwan and defeated the rebellion; Lin was executed.[170][169]

Invasions

By 1831, the East India Company decided it no longer wanted to trade with the Chinese on their terms and planned more aggressive measures. Given the strategic and commercial value of Taiwan, there were British suggestions in 1840 and 1841 to seize the island. William Huttman wrote to Lord Palmerston pointing out "China's benign rule over Taiwan and the strategic and commercial importance of the island."[171] He suggested that Taiwan could be occupied with only a warship and less than 1,500 troops, and the English would be able to spread Christianity among the natives as well as develop trade.[172] In 1841, during the First Opium War, the British tried to scale the heights around the harbor of Keelung three times but failed.[173] The British transport ship Nerbudda became shipwrecked near Keelung Harbour due to a typhoon. In October 1841, HMS Nimrod sailed to Keelung to search for the Nerbudda survivors, but after Captain Joseph Pearse found out that they were sent south for imprisonment, he ordered the bombardment of the harbour and destroyed 27 sets of cannon before returning to Hong Kong. The brig Ann also shipwrecked in March 1842. The commanders of Taiwan, Dahonga and Yao Ying, filed a disingenuous report to the emperor, claiming to have defended against an attack from the Keelung fort. Most of the survivors—over 130 from the Nerbudda and 54 from the Ann—were executed in Tainan in August 1842. The false report was later discovered and the officials in Taiwan punished.[171]

On 12 March 1867, the American barque Rover shipwrecked offshore off of southern Taiwan. The captain, his wife, and some men escaped. The Koaluts (Guizaijiao) tribe of the Paiwan people captured and killed them. Two rescue attempts failed.[174][175] Le Gendre, the US Consul, demanded that the Qing send troops to help him negotiate with the aborigines. On 10 September, Garrison Commander Liu Mingcheng led 500 Qing troops to southern Taiwan with Le Gendre. The aboriginal chief, Tanketok (Toketok), explained that a long time ago the white men came and almost exterminated the Koaluts tribe and their ancestors passed down their desire for revenge. They agreed that the mountain aborigines would help the castaways.[176] It was later discovered that Tanketok did not have absolute control over the tribes. Le Gendre castigated China as a semi-civilized power for not seizing the territory of a "wild race".[177]

In December 1871, a Ryukyuan vessel shipwrecked on the southeastern tip of Taiwan and 54 sailors were killed by aborigines.[178] The shipwreck and murder of the sailors came to be known as the Mudan incident, although it did not take place in Mudan (J. Botan), but at Kuskus (Gaoshifo).[179] The Ryukyu Kingdom did not ask Japanese officials for help regarding the shipwreck. Instead its king, Shō Tai, sent a reward to Chinese officials in Fuzhou for the return of the 12 survivors. The Mudan incident did not immediately cause any concern in Japan; it was not until April 1874 that it became an international concern.[180] The Imperial Japanese Army started urging the government to invade Taiwan in 1872. The king of Ryukyu was dethroned by Japan and preparations for an invasion of Taiwan were undertaken in the same year.[181] On 17 May 1874, Saigō Jūdō led the main force, 3,600 strong, aboard four warships.[182] On 3 June, they burnt all the villages that had been occupied. On 1 July, the new leader of the Mudan tribe and the chief of Kuskus surrendered.[183] The Japanese settled in and established large camps with no intention of withdrawing, but in August and September 600 soldiers fell ill. The death toll rose to 561. Negotiations with Qing China began on 10 September. The Western Powers pressured China not to cause bloodshed with Japan as it would negatively impact the coastal trade. The resulting Peking Agreement was signed on 30 October. Japan gained the recognition of Ryukyu as its vassal and an indemnity payment of 500,000 taels. Japanese troops withdrew from Taiwan on 3 December.[184]

During the Sino-French War, the French invaded Taiwan during the Keelung Campaign in 1884. On 5 August 1884, Sébastien Lespès bombarded Keelung's harbor and destroyed the gun placements. The next day, the French attempted to take Keelung but failed to defeat the larger Chinese force led by Liu Mingchuan and were forced to withdraw. On 1 October, Amédée Courbet landed with 2,250 French forces and defeated a smaller Chinese force, capturing Keelung. French efforts to capture Tamsui failed. The French shelled Tamsui, destroying not only the forts but also foreign buildings. Some 800 French troops landed on Shalin beach near Tamsui but they were repelled by Chinese forces.[185] The French imposed a blockade Taiwan from 23 October 1884 until April 1885 but the execution was not completely effective.[186] French ships around mainland China's coast attacked any junk they could find and captured its occupants to be shipped to Keelung for constructing defensive works. However for every junk the French captured, another five junks arrived with supplies at Takau and Anping. The immediate effect of the blockade was a sharp in decline of legal trade and income.[187]

In late January 1885, Chinese forces suffered a serious defeat around Keelung. Although the French captured Keelung they were unable to move beyond its perimeters. In March the French tried to take Tamsui again and failed. At sea, the French bombarded Penghu on 28 March.[188] Penghu surrendered on 31 March but many of the French soon grew ill and 1,100 soldiers and later 600 more were debilitated.[189] An agreement was reached on 15 April 1885 and an end to hostilities was announced. The French evacuation from Keelung was completed on 21 June 1885 and Penghu remained under Chinese control.[190]

End of Qing rule

As part of the settlement for losing the Sino-Japanese War, the Qing empire ceded the islands of Taiwan and Penghu to Japan on April 17, 1895, according to the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The loss of Taiwan would become a rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed.[191]

Japanese Empire (1895–1945)

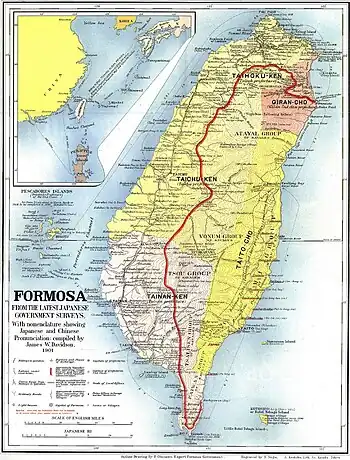

The acquisition of Taiwan by Japan was the result of Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi's "southern strategy" adopted during the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95. Itō and Mutsu Munemitsu, the minister of foreign affairs, stipulated that Penghu and Taiwan must be ceded to Japan. These conditions were met during the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki on 17 April 1895. Taiwan and Penghu were transferred to Japan on 2 June.[192][193]

The period of Japanese rule in Taiwan has been divided into three periods under according to policies: military suppression (1895–1915), dōka (同化): assimilation (1915–37), and kōminka (皇民化): Japanization (1937–45). A separate policy for aborigines was implemented.[194][195] The matter of assimilation, dōka (同化), was tied to the admonition "impartiality and equal favor" (isshi dōjin) for all imperial subjects under the Japanese Emperor. Conceptually this colonial ideal conveyed the idea that metropolitan Japanese (naichijin) imparted their superior culture to the subordinate islanders (hontōjin), who would share the common benefits.[196]

Armed resistance

The colonial authorities encountered violent opposition in Taiwan. Five months of sustained warfare occurred after the 1895 invasion and partisan attacks continued until 1902. For the first two years the colonial authority relied mainly on military force. On 20 May, Qing officials were ordered to leave their posts. General mayhem and destruction ensued in the following months.[197]

Japanese forces landed on the coast of Keelung on 29 May. After the fall of Taipei on 7 June, local militia and partisan bands continued the resistance. In the south, a small Black Flag force led by Liu Yongfu delayed Japanese landings. Governor Tang Jingsong attempted to carry out anti-Japanese resistance efforts as the Republic of Formosa.[197] The Green Standard Army and Yue soldiers from Guangxi took to looting and pillaging. Taipei's gentry elite sent Koo Hsien-jung to Keelung to invite the advancing Japanese forces to proceed to Taipei and restore order.[198] The Republic, established on 25 May, disappeared 12 days later when its leaders left for the mainland.[197] Liu Yongfu formed a temporary government in Tainan before escaping as Japanese forces closed in.[199] Between 200,000 and 300,000 people fled Taiwan in 1895.[200][201] Chinese residents in Taiwan were given the option of selling their property and leaving by May 1897, or become Japanese citizens. From 1895 to 1897, an estimated 6,400 people sold their property and left Taiwan.[202][203]

Armed resistance by Hakka villagers broke out in the south. A series of attacks led by "local bandits" or "rebels" lasted throughout the next seven years. After 1897, uprisings by Chinese nationalists were commonplace. Luo Fuxing, a member of the Tongmenghui, was arrested and executed along with 200 others in 1913.[204] In June 1896, 6,000 Taiwanese were slaughtered in the Yunlin Massacre. From 1898 to 1902, some 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed in addition to the 6,000–14,000 killed in the initial resistance war of 1895.[199][205]

Major armed resistance was largely crushed by 1902 but minor rebellions started occurring again in 1907, such as the Beipu uprising by Hakka and Saisiyat people in 1907, Luo Fuxing in 1913 and the Tapani Incident of 1915.[206][207] The Beipu uprising occurred on 14 November 1907 when a group of Hakka insurgents killed 57 Japanese officers and members of their family. In response, 100 Hakka men and boys were killed in the village of Neidaping.[208] Luo Fuxing was an overseas Taiwanese Hakka involved with the Tongmenghui. He planned a rebellion against the Japanese with 500 fighters, resulting in the execution of more than 1,000 Taiwanese by Japanese police. Luo was killed on 3 March 1914.[205][209] In 1915, Yu Qingfang organized a religious group that defied Japanese authority. In the Tapani incident, 1,413 members of Yu's group were captured. Yu and 200 of his followers were executed.[210] After the Tapani rebels were defeated, Andō Teibi a massacre. Military police in Tapani and Jiasian lured out anti-Japanese militants with a pardon. They were to line up in a field, dig holes, and then executed by firearm. According to oral tradition, some 5,000–6,000 people died in this incident.[211][212]

Non-violent resistance

.svg.png.webp)

Nonviolent means of resistance such as the Taiwanese Cultural Association (TCA), founded by Chiang Wei-shui in 1921, continued after most violent means were exhausted. Chiang joined the "Chinese United Alliance" founded by Sun Yat-sen. He saw Taiwanese people as Japanese nationals of Han Chinese ethnicity and wished to position the TCA as an intermediary between China and Japan. The TCA also aimed to establish independence for Taiwan.[213] Statements of self determination were possible at the time due to the relatively progressive era of Taishō Democracy. "Taiwan is Taiwan people's Taiwan" became a common position for all anti-Japanese groups. In December 1920, Lin Hsien-tang and 178 Taiwanese residents filed a petition seeking self-determination. It was rejected.[214]

The TCA had over 1,000 members of various backgrounds from across Taiwan except in indigenous areas. The TCA promoted vernacular Chinese language. In 1923 the TCA co-founded Taiwan People's News which was published in Tokyo and then shipped to Taiwan. It was subjected to censorship and seven or eight issues were banned. Chiang and others applied to set up a parliament for Taiwan that was deemed illegal. In 1923, 99 Alliance members were arrested and 18 were tried in court.[215] Thirteen were convicted. Chiang was imprisoned more than ten times.[216]

The TCA split in 1927 to form the New TCA and the Taiwanese People's Party, which both Chiang and Lin left for. The New TCA later became a subsidiary of the Taiwanese Communist Party and the only organization advocating Taiwanese independence. The TPP brought forth issues such as Japanese opium trafficking, the inhumane treatment of the Seediq people, and revealed the colonial authority's use of poisonous gas. In February 1931, the TPP was terminated. Chiang died on 23 August.[217]

Assimilation movement

In 1914, Itagaki Taisuke briefly led a Taiwan assimilation movement as a response to appeals from influential Taiwanese spokesmen. In December 1914, Itagaki formally inaugurated the Taiwan Dōkakai, an assimilation society. Within a week, over 3,000 Taiwanese and 45 Japanese residents joined the society. After Itagaki left later that month, leaders of the society were arrested and its Taiwanese members detained or harassed. In January 1915, the Taiwan Dōkakai was disbanded.[218]

Japanese colonial policy sought to strictly segregate the Japanese and Taiwanese population until 1922.[219] Taiwanese students who moved to Japan for their studies were able to associate more freely with Japanese and took to Japanese ways more readily than their island counterparts. However full assimilation was rare.[220]

An attempt to fully Japanize the Taiwanese people was made during the kōminka period (1937–45). The reasoning was that only as fully assimilated subjects could Taiwan's inhabitants fully commit to Japan's war and national aspirations.[221] The kōminka movement was generally unsuccessful and few Taiwanese became "true Japanese" due to the short time period and large population. In terms of acculturation under controlled circumstances, it can be considered relatively effective.[222]

Education

A system of elementary common schools taught Japanese language and culture, Classical Chinese, Confucian ethnics, and practical subjects like science.[223] The emphasis was on Japanese language and ethics while Classical Chinese was included to mollify upper-class Taiwanese parents.[224] These schools served a small percentage of the Taiwanese population and Japanese children attended their own primary schools. Post-elementary education was rare for Taiwanese people and a portion of the population continued to enroll in Qing-style private schools due to limited access to government educational institutions. Most boys attended Chinese schools while a smaller portion trained at religious schools. Elementary education was offered to those Taiwanese who could afford it.[223]

The gentry was urged to promote the "new learning" and those invested in the Chinese education style were resentful of the proposal. Younger Taiwanese started participating in community affairs in the 1910s. Many were concerned about obtaining modern educational facilities and the discrimination they faced in obtaining spots at the few government schools. Local leaders in Taichung campaigned for the inauguration of the Taichū Middle School but faced opposition from Japanese officials.[225]

In 1922, an integrated school system was introduced opening common and primary schools to both Taiwanese and Japanese based on Japanese language proficiency.[226] Few Taiwanese children could speak fluent Japanese and only the children of wealthy Taiwanese families with close ties to Japanese settlers were allowed to study alongside Japanese children.[227] The number of Taiwanese at formerly Japanese-only elementary schools was limited to 10 percent.[224] Some Taiwanese sought secondary education and opportunities in Japan and Manchukuo.[224] In 1943, primary education became compulsory, and by the next year nearly three out of four children were enrolled in primary school.[228] By 1922, around 2,000 Taiwanese students were enrolled in metropolitan Japan, increasing to 7,000 by 1942.[220]

Japanization

After full-scale war with China in 1937, the "kōminka" imperial Japanization project was implemented to ensure the Taiwanese would remain subjects of the Japanese Emperor rather than support a Chinese victory. The goal was to make sure the Taiwanese people did not develop a sense of national identity.[229] Although the stated goal was to assimilate the Taiwanese, in practice the process segregated the Japanese into their discrete areas, despite co-opting Taiwanese leaders.[230] The organization was responsible for increasing war propaganda, donation drives, and regimenting Taiwanese life.[231]

As part of the policies, Chinese language in newspapers and education were removed.[221] China and Taiwan's history were erased from the curriculum.[229] Chinese language use was discouraged. However even some members of model "national language" families from well-educated Taiwanese households failed to learn Japanese to a conversational level. A name-changing campaign was launched in 1940 to replace Chinese names with Japanese ones. Seven percent of the Taiwanese had done so by the end of the war.[221] Characteristics of Taiwanese culture considered "un-Japanese" or undesirable were banned or discouraged. The Taiwanese were encouraged to pray at Shinto shrines. Some officials removed religious idols and artifacts from native places of worship.[232]

Aboriginal policies

Japan continued the Qing classification of aborigines. Acculturated aborigines lost their aboriginal status. Han Chinese and shufan were both treated as Taiwanese by the Japanese. Below them were the semi-acculturated and non-acculturated "barbarians" outside normal administrative units and Japanese law.[233] According to the Sōtokufu (Office of the Governor-General), mountain aborigines were animals under international law.[234] The Sōtokufu declared all unreclaimed and forest land in Taiwan as government property, forbidding any new use of forest land.[235] The Japanese authority denied aboriginal rights to their property and land. Han and acculturated aborigines were forbidden from any contractual relationships with aborigines.[236] The aborigines could not enjoy property ownership and acculturated aborigines lost their rent holder rights under the new property laws.[234][237]

Initially the Japanese spent most of their time fighting Chinese insurgents and the government took on a more conciliatory approach towards aborigines. In 1903, the government implemented harsher policies. It expanded guard lines to restrict the aborigines' living space. Sakuma Samata launched a five-year plan for aboriginal management, attacking aborigines and using landmines and electrified fences to force them into submission.[238]

A small portion of land was set aside for aboriginal use. From 1919 to 1934, aborigines were relocated to out of the way areas. A small compensation for land use was initially given out but discontinued later on. In 1928, each aborigine was allotted three hectares of reserve land. Some of the allotted land was taken away and it was discovered that the aboriginal population was bigger than the estimated 80,000. The allotted land was reduced but they were not adhered to anyways. In 1930, the government relocated aborigines to the foothills. They were given less than half the originally promised land, or one-eighth of their ancestral lands.[239][240]

Aboriginal resistance lasted until the early 1930s.[206] By 1903, indigenous rebellions had resulted in the deaths of 1,900 Japanese.[241] In 1911, an army invaded Taiwan's mountainous areas and by 1915, many aboriginal villages had been destroyed. The Atayal and Bunun resisted the hardest.[242] The last major aboriginal rebellion, the Musha (Wushe) Uprising occurred on 27 October 1930 when the Seediq people launched the last headhunting party. Seediq warriors led by Mona Rudao attacked police stations and the Musha Public School. Approximately 350 students, 134 Japanese, and 2 Han Chinese were killed. The armed conflict ended in December when the Seediq leaders committed suicide.[243][244] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the war against the aboriginals numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[245] After the Musha Incident, the government took a more conciliatory stance towards the aborigines.[238]

Japanese colonists

Japanese commoners started arriving in Taiwan in April 1896.[246] Japanese migrants were encouraged to move to Taiwan but few did during the colony's early years. Concern that Japanese children born in Taiwan would not be able to understand Japan resulted in primary schools conducting trips to Japan in the 1910s. Japanese police officers were encouraged to learn the Minnan and Hakka languages. Police officers who passed language examinations received allowances and promotions.[227] By the late 1930s, Japanese people made up about 5.4 percent of Taiwan's population but owned a disproportionate amount of high quality land (20–25 percent of cultivated land) as well as the majority of large land holdings. The government assisted them in acquiring land and coerced Chinese land owners to sell. Japanese sugar companies owned 8.2 percent of the arable land.[247]

There were almost 350,000 Japanese civilians living in Taiwan by the end of World War II.[248] Offspring of intermarriage were considered Japanese if their Taiwanese mother chose Japanese citizenship or if their Taiwanese father did not apply for ROC citizenship.[249] As many as half the Japanese who left Taiwan after 1945 were born in Taiwan.[248] The Taiwanese seized or attempted to occupy property they believed were unfairly obtained in previous decades.[250] Japanese assets were collected and the ROC government retained most of it for their use.[251] Chen Yi, who was in charge of Taiwan, removed Japanese bureaucrats and police officers from their posts. A survey found that 180,000 Japanese civilians wished to leave for Japan while 140,000 wished to stay.[252] From February to May, the vast majority of Japanese left Taiwan for Japan.[253]

Industrialization

Under the colonial government, Taiwan was introduced to a unified system of weights and measures, a centralized bank, education facilities to increase skilled labor, farmers' associations, and other institutions. Transportation and communications systems as well as facilities for travel between Japan and Taiwan were developed. Construction of large scale irrigation facilities and power plants followed. Agricultural development was the goal of colonial projects and the objective was for Taiwan to provide Japan with food and raw materials. Fertilizer and production facilities were imported from Japan. Textile and paper industries were developed near the end of Japanese rule for self-sufficiency. All modern and large enterprises were owned by the Japanese.[254]

The Taiwan rail system connecting the south and the north and the Kīrun and Takao ports were completed to facilitate transport and shipping of raw material and agricultural products.[255] Exports increased fourfold. Fifty-five percent of agricultural land was covered by dam-supported irrigation systems. Food production increased fourfold and sugar cane production increased 15-fold between 1895 and 1925. Taiwan became a major foodbasket serving Japan's economy. A health care system was established. The average lifespan for a Taiwanese resident was 60 years by 1945.[256]

Taiwan's real GDP per capita peaked in 1942 at $1,522 and declined to $693 by 1944.[257] Wartime bombing caused significant damage to cities and harbors. The railways and factories were either badly damaged or destroyed.[258] Only 40 percent of the railroads were usable and over 200 factories were bombed. Of Taiwan's four electrical power plants, three were destroyed.[259] Damage to agriculture was relatively contained but most developments came to a halt and irrigation facilities were abandoned. Since all key positions were held by Japanese, their departure left Taiwan with a severe lack of trained personnel. Inflation was rampant as a result of the war.[258] Taiwan's standards of living did not recover until the 1960s.[260]

World War II

As Japan embarked on full-scale war with China in 1937, expanding Taiwan's industrial capacity to manufacture war material. The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily out of Taiwan. The "South Strike Group" was based out of the Taihoku Imperial University. Taiwan was used as a launchpad for the invasion of Guangdong in late 1938 and for the occupation of Hainan in February 1939. A joint planning and logistical center was established in Taiwan to assist Japan's southward advance after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.[261] Taiwan served as a base for Japanese naval and air attacks on Luzon until the surrender of the Philippines in May 1942. It served as a rear staging ground for attacks on Myanmar. As the war turned against Japan in 1943, Taiwan suffered due to Allied submarine attacks on Japanese shipping. In the latter part of 1944, Taiwan was bombed in U.S. air raids.[262] An estimated 16,000–30,000 civilians were killed.[263] By 1945, Taiwan was isolated from Japan.[262]

Starting in July 1937, Taiwanese began to play a role on the battlefield, initially in noncombatant positions. Taiwanese people were not recruited for combat until late in the war. In 1942, the Special Volunteer System was implemented, allowing even aborigines to be recruited as part of the Takasago Volunteers. From 1937 to 1945, over 207,000 Taiwanese were employed by the Japanese military. Roughly 50,000 went missing in action or died, another 2,000 were disabled, 21 were executed for war crimes, and 147 were sentenced to imprisonment for two or three years.[264] Some Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers claim they were coerced and did not choose to join the army.[265] Racial discrimination was commonplace despite rare occasions of camaraderie. After Japan's surrender, the Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers were abandoned by Japan and no transportation back to Taiwan or Japan was provided. Many of them faced difficulties in mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan. An organization of Taiwanese ex-Japanese soldiers tried to get the Japanese government to pay their unpaid wages several decades later. They failed.[266]

Between 1,000 and 2,000 Taiwanese women were part of the comfort women system. Aboriginal women served Japanese military personnel in the mountainous region of Taiwan. They were first recruited as housecleaning and laundry workers for soldiers, then they were coerced into providing sex. They were gang-raped and served as comfort women in the evening hours. Han Taiwanese women from low income families were also part of the comfort women system. Some were pressured into it by financial reasons while others were sold by their families.[267] However some women from well to do families also ended up as comfort women.[268] More than half were minors with some as young as 14. Very few women who were sent overseas understood what the true purpose of their journey was.[267] Some of the women believed they would be serving as nurses. Taiwanese women were told to provide sexual services to the Japanese military "in the name of patriotism to the country."[268] By 1940, brothels were set up in Taiwan to service Japanese males.[267]

End of Japanese rule