Pixodarus

Pixodarus or Pixodaros (in Lycian 𐊓𐊆𐊜𐊁𐊅𐊀𐊕𐊀 Pixedara; in Greek Πιξώδαρoς; ruled 340–334 BC), was a satrap of Caria, nominally the Achaemenid Empire Satrap, who enjoyed the status of king or dynast by virtue of the powerful position his predecessors of the House of Hecatomnus (the Hecatomnids) created when they succeeded the assassinated Persian Satrap Tissaphernes in the Carian satrapy. Lycia was also ruled by the Carian dynasts since the time of Mausolus, and the name of Pixodarus as ruler appears in the Xanthos trilingual inscription in Lycia.

| Pixodarus | |

|---|---|

Portrait on Carian coinage of the time of Pixodaros.[1] | |

| Satrap of Caria | |

| Reign | 340–334 BC |

| Predecessor | Ada |

| Successor | Orontobates |

| House | Hecatomnids |

| Father | Hecatomnus |

| Hecatomnid dynasty (Dynasts of Caria) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Biography

He was the youngest of the three sons of Hecatomnus, all of whom held the sovereignty of their native country. Pixodarus obtained possession of the throne by the expulsion of his sister Ada, the widow of their brother Idrieus, with whom she had jointly governed Caria.[2] He ruled Caria without opposition for a period of four years, 340–334 BC. He cultivated the friendship with Persia, giving his daughter Ada in marriage to a Persian named Orontobates,[2] whom he even seems to have admitted to some share in the sovereign power during his own lifetime.

But, he did not neglect to court the alliance of other powers also, and endeavoured to secure the powerful friendship of Philip II, king of Macedonia, by offering the hand of his eldest daughter in marriage to Arrhidaeus, the eldest, but disabled, son of the Macedonian monarch. The discontent of the young Alexander at this period led him to offer himself as a suitor for the Carian princess instead of his brother — an overture which was eagerly embraced by Pixodarus, but the indignant interference of Philip put an end to the whole scheme.

Pixodarus died — apparently a natural death — some time before the landing of Alexander in Asia, 334 BC: and was succeeded by his son-in-law the Persian Orontobates, who had married his daughter Ada II. Orontobates was soon ousted by Alexander the Great in the Siege of Halicarnassus, and replaced by Princess Ada with the approval of Alexander.[4]

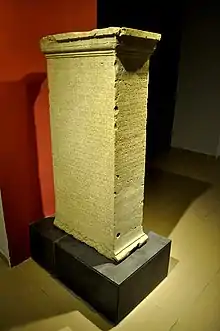

Decree of Pixodarus

A fragment of a bilingual decree by Pixodarus in Greek and Lycian was discovered at Xanthos in Turkey, and is now held at the British Museum in London. The inscription records grants made by Pixedara (Pixodarus) to the Lycian cities of Arñna (Xanthos), Pñ (Pinara), Tlawa (Tlos) and Xadawãti (Kadyanda).[5]

| Content | Transcription | Transliteration (original Lycian script) | Inscription |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Record of tax privileges from Pixedara (Pixodaros) for the Lycian cities of Arñna (Xanthos), Pñ (Pinara), Tlawa (Tlos) and Xadawãti (Kadyanda).[6][7] |

eñnẽ pixe[d]ar(a) ekat[m̃mna] |

|

The bilingual Greek-Lycian Decree of Pixodaros, showing the incomplete inscription in the Lycian script, found at Xanthos. |

Xanthos trilingual inscription

Pixadorus is also mentioned in the Xanthos trilingual inscription, confirming the rule of Pixodarus over neighbouring Lycia:

In the month Siwan, year 1 of King Artaxerxes. In the fortress of Arñna (Xanthos). Pixodarus son of Katomno (Hecatomnus), the satrap who is in Karka (Caria) and Termmila (Lycia)....[8]

When Pixodarus, the son of Hecatomnus, became satrap of Lycia, he appointed as rulers of Lycia Hieron (ijeru) and Apollodotos (natrbbejẽmi), and as governor (asaxlazu) of Xanthus, Artemelis (erttimeli).

The Artaxerxes in question is thought to be Artaxerxes IV.

Coinage

He ordered the minting of his own golden coins, a right at time exclusively reserved to the King of Persia. [9]

Coinage of Pixodaros, circa 341/0 to 336/5 BCE. Obv: Head of Apollo facing right, wearing laurel wreath, drapery at neck. Rev: Zeus Labraundos standing right; Legend ΠIΞOΔAPOY, "Pixodaros".

Coinage of Pixodaros, circa 341/0 to 336/5 BCE. Obv: Head of Apollo facing right, wearing laurel wreath, drapery at neck. Rev: Zeus Labraundos standing right; Legend ΠIΞOΔAPOY, "Pixodaros". Coinage of Pixodaros, circa 341/0 to 336/5 BCE. Obv: Head of Apollo, wearing laurel wreath. Rev: Zeus Labraundos standing right; Legend ΠIΞOΔAPOY, "Pixodaros".

Coinage of Pixodaros, circa 341/0 to 336/5 BCE. Obv: Head of Apollo, wearing laurel wreath. Rev: Zeus Labraundos standing right; Legend ΠIΞOΔAPOY, "Pixodaros".

References

- Smith, William (editor); Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Pixodarus (2)", Boston, (1867)

Notes

- Precise date of 341-334 BC according to Meadows CNG: CARIA, Achaemenid Period. Circa 350-334 BC. AR Tetradrachm (15.07 g, 12h). Struck circa 341-334 BC.

- Sears, Matthew A. (2014). "Alexander and Ada Reconsidered". Classical Philology. 109 (3): 213. doi:10.1086/676285. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 10.1086/676285. S2CID 170273543 – via JSTOR.

- Precise date of 341-334 BC according to Meadows CNG: CARIA, Achaemenid Period. Circa 350-334 BC. AR Tetradrachm (15.07 g, 12h). Struck circa 341-334 BC.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca, xvi. 74; Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri, i. 23; Strabo, Geography, xiv. 2; Plutarch, Parallel Lives, "Alexander", 10

- British Museum collection

- Hansen, Mogens Herman; Nielsen, Thomas Heine; Nielsen, Lecturer in the Department of Greek and Latin Thomas Heine (2004). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis. OUP Oxford. p. 1141. ISBN 9780198140993.

- Bresson, Alain (2015). The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy: Institutions, Markets, and Growth in the City-States. Princeton University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9781400852451.

- Teixidor, Javier (April 1978). "The Aramaic Text in the Trilingual Stele from Xanthus". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 37 (2): 181–185. doi:10.1086/372644. JSTOR 545143. S2CID 162374252.

- Sears, Matthew A. (2014) p.216

External links

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Pixodarus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Pixodarus". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.