Eshmunazar II

Eshmunazar II ([æʃmuːn ʔɑːzər] ⓘ; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓, ʾšmnʿzr, meaning "Eshmun helps") was the Phoenician king of Sidon[1] (r. c. 539 – c. 525 BC). He was the grandson of Eshmunazar I, and a vassal king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar II succeeded his father Tabnit I who ruled for a short time and died before the birth of his son. Tabnit I was succeeded by his sister-wife Amoashtart who ruled alone until Eshmunazar II's birth, and then acted as his regent until the time he would have reached majority. Eshmunazar II died prematurely at the age of 14. He was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.

| Eshmunazar II | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Phoenician-inscribed sarcophagus of king Eshmunazar II from the Sidon royal necropolis, the Louvre | |

| Reign | c. 539 BC – c. 525 BC |

| Predecessor | Tabnit I |

| Successor | Bodashtart (his cousin) |

| Burial | Sidon royal necropolis |

| Phoenician language | 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 |

| Dynasty | Eshmunazar I dynasty |

| Religion | Canaanite polytheism |

Eshmunazar II came from a lineage of priests of Astarte, and his rule saw a strong emphasis on religious activities. He and his mother Amoashtart built temples in various parts of Sidon and its neighboring territories. During his reign, King Cambyses II of Persia rewarded Sidon for its milirary contributions to his campaign against Egypt by granting Sidon additional territory. Eshmunazar II is primarily known from his sarcophagus, which features two Phoenician inscriptions; it is currently housed in the Louvre Museum.

Etymology

Eshmunazar is the Romanized form of the Phoenician theophoric name 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓, meaning "Eshmun helps".[2][3] Eshmun was the Phoenician god of healing and renewal of life; he was one of the most important divinities of the Phoenician pantheon and the main male divinity of the city of Sidon.[4]

The name is also transliterated as: ʾEšmunʿazor,[5] ʾšmnʿzr,[6] Achmounazar,[7] Ashmounazar,[8] Ashmunazar,[9] Ashmunezer,[10] Echmounazar,[11] Echmounazor,[12] Eschmoun-ʿEzer,[13] Eschmunazar,[14] Eshmnʿzr,[3] Eshmunazor,[15] Esmounazar,[16] Esmunasar,[17] Esmunazar,[18] Ešmunʿazor,[19] Ešmunazar,[20] Ešmunazor.[21]

Historical context

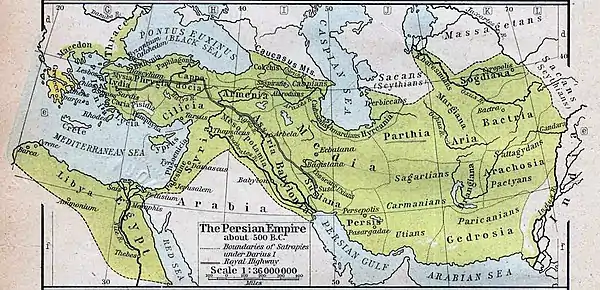

Sidon, which was a flourishing and independent Phoenician city-state, came under Mesopotamian occupation in the ninth century BC. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883 – 859 BC) conquered the Lebanon mountain range and its coastal cities, including Sidon.[22] In 705, King Luli, who reigned over both Tyre and Sidon,[23] joined forces with the Egyptians and Judah in an unsuccessful rebellion against Assyrian rule.[24][25] He was forced to flee to Kition in the neighboring island of Cyprus with the arrival of the Assyrian army headed by Sennacherib. Sennacherib placed Ittobaal on the throne of Sidon and imposed an annual tribute.[lower-alpha 1][27] Elayi believes that Ittobaal was of royal Sidonian lineage, a family line driven out of power by the reigning Tyrian kings.[28] When Abdi-Milkutti ascended to Sidon's throne in 680 BC, he also rebelled against the Assyrians. In response, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon captured and beheaded Abdi-Milkutti in 677 BC after a three-year siege; Sidon was stripped of its territory, which was awarded to Baal I, the king of rival Tyre and loyal vassal to Esarhaddon.[29]

Sidon returned to its former prosperity while Tyre was besieged for thirteen years (586–573 BC) by the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar II.[30] After the Achaemenid conquest in 529 BC. Phoenicia was divided into four vassal kingdoms: Sidon, Tyre, Byblos and Arwad.[31] Eshmunazar I, a priest of the Phoenician goddess Astarte, and the founder of his eponymous dynasty, became king around the same time.[32] During the early Persian period (539–486 BC), Sidon rose to power, becoming Phoenicia's preeminent city.[33][34][35] Sidonian kings began an extensive program of mass-scale construction projects attested in the funerary inscription on the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II and the dedicatory Bodashtart inscriptions found on the foundations of the Temple of Eshmun's monumental podium.[36][37][38]

Reign

Chronology and length of reign

Eshmunazar is believed to have reigned in the later half of the sixth century BC, during the Persian Achaemenid Period of Sidon's history, from c.539 BC until his premature death c.525 BC.[39][40] The absolute chronology of the kings of Sidon from the dynasty of Eshmunazar I onward has been much discussed in the literature; traditionally placed in the course of the fifth century BC, inscriptions of this dynasty have been dated back to an earlier period on the basis of numismatic, historical and archaeological evidence. The most complete work addressing the dates of the reigns of these Sidonian kings is by the French historian Josette Elayi, who shifted away from the use of biblical chronology.[39] Elayi placed the reigns of the descendants of Eshmunazar I between the middle and the end of the sixth century BC.[39][40] Elayi used all available documentation of the time, including inscribed Tyrian seals,[41] and stamps excavated by the Lebanese archaeologist Maurice Chehab in 1972 from Jal el-Bahr, a neighborhood in the north of Tyre.[42] She also used Phoenician inscriptions discovered by the French archaeologist Maurice Dunand in Sidon in 1965,[43] and conducted a systematic study of Sidonian coins, the first coins to bear minting dates representing the years of Sidonian kings’ reigns.[44][45]

Temple building and territorial expansion

The kings of Sidon held priestly in addition to military, judiciary and diplomacy responsibilities. Among the Sidonian kings' various duties, priestly functions were given particular importance as is highlighted by the place of the priestly title, which preceded the royal title and the patronym in the royal inscriptions of Eshmunazar I and Tabnit.[46][47] Some locally minted coins display scenes suggesting that the Sidonian kings actively participated in religious ceremonies.[47] Eshmunazar II descended from a line of priests; his father Tabnit and his grandfather Eshmunazar I were priests of Astarte, in addition to being kings of Sidon, as recorded on Tabnit's sarcophagus inscriptions.[lower-alpha 2] Eshmunazar II's mother was also a priestess of Astarte as illustrated on line 14 of her son's sarcophagus inscriptions.[49] The construction and restoration of temples and the execution of priestly duties served as promotional tools used by Sidonian monarchs to bolster their political power and magnificence, and to depict them as pious recipients of divine favor and protection.[47] This royal function was manifested by Eshmunazar II and his mother Queen Amoashtart through the construction of new temples and religious buildings for the Phoenician gods Baal, Astarte, and Eshmun in a number of Sidon's neighborhoods and its adjoining territory.[lower-alpha 3][47][50]

In recognition to Sidon's naval warfare contributions, the Achaemenids awarded Eshmunazar II the territories of Dor, Joppa, and the plain of Sharon.[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5][52]

Succession and death

Phoenician royalty was lifelong and hereditary.[15] The responsibilities and power of the position were passed down to the regent's child or another member of their family when they die. The royal ancestry and lineage of Sidonian kings was documented up to the second or third-degree ancestor (see line 13 and 14 of Eshmunazar II's sarcophagus inscription).[53] Queen mothers held political power and exercised in the form of association with political acts and co-regency.[54] Eshmunazar II's father King Tabnit I ruled for a short time and died before the birth of his son, he was succeeded by his sister-wife Amoashtart who assumed the role of regent during the interregnum, ruled alone until Eshmunazar II's birth, and then acted as his regent until the time he would have reached majority. Eshmunazar II died aged 14 during the reign of his overlord Cambyses II of Achaemenid Persia.[55][56] After his premature death Eshmunazar II was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.[35]

Eshmunazar II's sarcophagus

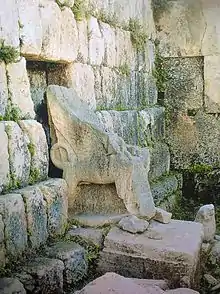

The sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II is one of the only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's parents, King Tabnit and Queen Amoashtart.[57][58] It was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite for a member of the Egyptian elite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC.[59][60][61] The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head.[62][63][64] The sarcophagus was discovered on 19 January 1855 when treasure-hunters were digging in the grounds of an ancient cemetery in the plains south of the city of Sidon. It was found outside a hollowed-out rocky mound locally known as Magharet Abloun ('The Cavern of Apollo'), a part of a large complex of Achaemenid era necropoli.[65][62][66][67][68] The discovery is attributed to Alphonse Durighello, an agent of the French consulate in Sidon, who informed and sold the sarcophagus to Aimé Péretié, an amateur archaeologist and the chancellor of the French consulate in Beirut.[69][70] The sarcophagus was first described,[62] and acquired by Honoré Théodoric d'Albert de Luynes, a French aristocrat who donated it to the French state.[71] The sarcophagus of King Eshmunazar II is housed in the Louvre's Near Eastern antiquities section in room 311 of the Sully wing. It was given the museum identification number of AO 4806.[67]

The inscriptions of the sarcophagus of Eshmunazardi are written in the Phoenician language, in the Phoenician alphabet. They identify the king buried inside, tell of his lineage and temple construction feats and warns against disturbing him in his repose.[38][72] The inscriptions also state that the "Lord of Kings" (the Achaemenid King of Kings, probably Cambyses II)[73] granted the Sidonian king "Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of Dagon, which are in the plain of Sharon" in recognition of his deeds.[38] The deeds in question probably relate to the contribution of Eshmunazar to the Egyptian campaign of Cambyses II.[73] Copies of the inscriptions were sent to scholars across the world and translations were published by well-known scholars of the time.[74][75][76]

Genealogy

Eshmunazar II was a descendant of Eshmunazar I's dynasty. Eshmunazar's son Tabnit succeeded him. Tabnit had a child, Eshmunazar II, with his sister Amoashtart. Tabnit died before the birth of Eshmunazar II, and Amoashtart ruled in the interlude until the birth of her son, then was co-regent until he reached adulthood.[35][77]

| Eshmunazar I dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- I placed Tu-Baʾlu on his royal throne over them and imposed upon him tribute (and) payment (in recognition) of my overlordship (to be delivered) yearly (and) without interruption.[26]

- I, Tabnit, priest of Astarte, king of Sidon, the son of Eshmunazar, priest of Astarte, king of Sidon, am lying in this sarcophagus. Whoever you are, any man that might find this sarcophagus, don't, don't open it and don't disturb me, for no silver is gathered with me, no gold is gathered with me, nor anything of value whatsoever, only I am lying in this sarcophagus. Don't, don't open it and don't disturb me, for this thing is an abomination to Astarte. And if you do indeed open it and do indeed disturb me, may you not have any seed among the living under the sun, nor a resting-place with the Rephaites.[48]

- See lines 15–18 of the Eshmunazar II sarchophagus inscription.

- See lines 18–20 of the Eshmunazar II sarchophagus inscription.

- The territories of the Phoenician cities could be discontinuous: thus, the lands and the cities of Dor and Joppa belonging to the Sidonians were separated from Sidon by the city of Tyre.[51]

References

Citations

- Haelewyck 2012.

- Hitti 1967, p. 135.

- Jean 1947, p. 267.

- Jayne 2003, pp. 136–140.

- Burlingame 2018.

- Briquel Chatonnet, Daccache & Hawley 2015, p. 237.

- Delattre 1890, p. 17.

- Mariette 1856, p. 9.

- Wilson 1982, p. 46.

- Turner 1860, p. 48.

- Clermont-Ganneau 1880, p. 93.

- Bordreuil 2002.

- Munk 1856.

- Hitzig 1855.

- Elayi 1997, p. 68.

- Perrot & Chipiez 1885, p. 168.

- Levy 1864, p. 227.

- duc de Luynes 1856, p. 55.

- Elayi 2004, p. 9.

- Eiselen 1907, p. 73.

- King 1997, p. 189.

- Bryce 2009, p. 651.

- Elayi 2018b, pp. 55–58, 72.

- Netanyahu 1964, pp. 243–244.

- Yates 1942, p. 109.

- Sennachérib 2012.

- Elayi 2018b, p. 58.

- Elayi 2018a, p. 165.

- Bromiley 1979, pp. 501, 933–934.

- Aubet 2001, pp. 58–60.

- Boardman et al. 2000, p. 156.

- Zamora 2016, p. 253.

- Katzenstein 1979, p. 24.

- Zamora 2016, pp. 253–254.

- Elayi 2006, p. 5.

- Zamora 2016, pp. 255–257.

- Elayi 2006, p. 7.

- Pritchard & Fleming 2011, pp. 311–312.

- Elayi 2006, p. 22.

- Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 6.

- Elayi 2006, p. 2.

- Kaoukabani 2005, p. 3; Chéhab 1983, p. 171; Greenfield 1985, pp. 129–134.

- Dunand 1965, pp. 105–109.

- Elayi 2006.

- Elayi & Elayi 2004.

- Elayi 1997, p. 69.

- Elayi & Sapin 1998, p. 153.

- Jidejian & Dunand 2006, p. 25.

- Haelewyck 2012, pp. 80–81.

- Amadasi Guzzo 2012.

- Elayi 1997, p. 66.

- Briant 2002, p. 490.

- Elayi 1997, pp. 68–69.

- Elayi 1997, p. 70.

- Kessler 2020.

- Kelly 1987, p. 268.

- Dussaud, Deschamps & Seyrig 1931, Plaque 29.

- Kelly 1987, pp. 48–49.

- Elayi 2006, p. 6.

- Versluys 2011, pp. 7–14.

- Buhl 1983, p. 201.

- duc de Luynes 1856, p. 1.

- Turner 1860, pp. 48, 51–52.

- Gibson 1982, p. 105.

- Journal of Commerce staff 1856, pp. 379–380.

- Jidéjian 2000, pp. 17–18.

- Caubet & Prévotat 2013.

- Klat 2002, p. 101.

- Klat 2002, p. 102.

- Tahan 2017, pp. 29–30.

- King 1887, p. 135.

- Crawford 1992, pp. 180–181.

- Kelly 1987, pp. 46–47.

- Turner 1860, pp. 48–50.

- Turner 1860, p. 49.

- Haelewyck 2012, p. 82.

- Nabulsi 2017, pp. 307, 310.

Bibliography

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2012). "Sidon et ses sanctuaires" [Sidon and its sanctuaries]. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. 106: 5–18. doi:10.3917/assy.106.0005. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 42771737. OCLC 7293818994. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023.

- Aubet, María Eugenia (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, colonies and trade (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521795432. OCLC 906592970.

- Boardman, John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Lewis, David Malcolm; Ostwald, Martin (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean c.525 to 479 B.C. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521228046. OCLC 1043966300.

- Bordreuil, Pierre (2002). "À propos des temples dédiés à Echmoun par les rois Echmounazor et Bodachtart" [About temples dedicated to Echmoun by Kings Echmounazor and Bodachtart]. In Ciasca, Antonia; Amadasi, Maria Giulia; Liverani, Mario; Matthiae, Paolo (eds.). Da Pyrgi a Mozia : studi sull'archeologia del Mediterraneo in memoria di Antonia Ciasca [From Pyrgi to Mozia: studies on the archaeology of the Mediterranean in memory of Antonia Ciasca]. Vicino oriente (in French). Rome: Università degli studi di Roma "La sapienza". pp. 105–108. OCLC 53249170.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A history of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061207.

- Briquel Chatonnet, Françoise; Daccache, Jimmy; Hawley, Robert (January 2015). "Notes d'épigraphie et de philologie phéniciennes" [Notes of Phoenician epigraphy and philology]. Semitica et Classica (in French). 8: 235–248. doi:10.1484/J.SEM.5.109199.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey (1979). The International standard Bible encyclopedia: Q–Z. Vol. 4. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802837844. OCLC 4858038.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge handbook of the peoples and places of ancient western Asia : the Near East from the early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415394857. OCLC 466182477.

- Buhl, Marie Louise (1983). The Near Eastern pottery and objects of other materials from the upper strata. Copenhagen: Munksgaard. ISBN 9788773041253. OCLC 54263315.

- Burlingame, Andrew (January 2018). "'Ešmun 'azor's exchange: an old reading and a new interpretation of line 19 of 'Ešmun 'azor's sarcophagus inscription (AO 4806 = KAI 14)". Semitica et Classica. 11: 35–69. doi:10.1484/J.SEC.5.116794. ISSN 2031-5937. OCLC 8027039665.

- Caubet, Annie; Prévotat, Arnaud (2013). "Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, king of Sidon". Louvre Museum Official Website. Musée du Louvre. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- Chéhab, Maurice (1983). "Découvertes phéniciennes au Liban" [Phoenician discoveries in Lebanon]. Atti del I congresso internazionale di studi Fenici e Punici [Proceedings of the first International Congress of Phoenician and Punic studies] (in French). Rome. pp. 165–172. OCLC 85220069.

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles (1880). Études d'archeologie orientale [Eastern archaeology studies] (in French). Paris: F. Vieweg. OCLC 1072391350.

- Crawford, Timothy G. (1992). Blessing and curse in Syro-Palestinian inscriptions of the Iron Age. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 9780820416625. OCLC 23901422.

- Delattre, Alfred Louis (1890). Les tombeaux puniques de Carthage [The Punic tombs of Carthage] (in French). Lyon: Imprimerie Mougin-Rusand. OCLC 7507471.

- Dunand, Maurice (1965). "Nouvelles inscriptions phéniciennes du temple d'Echmoun, près Sidon" [New Phoenician inscriptions from the temple of Echmoun, near Sidon]. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth (in French). Beirut: Ministère de la Culture – Direction Générale des Antiquités (Liban). 18: 105–109. OCLC 1136062784.

- Dussaud, René; Deschamps, Paul; Seyrig, Henri (1931). La Syrie antique et médiévale illustrée [Ancient and medieval Syria illustrated] (in French). Vol. Tome XVII. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner. OCLC 64596292. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021 – via Gallica.

- Eiselen, Frederick Carl (1907). Sidon: A study in oriental history. New York: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/eise92800. hdl:2027/hvd.32044004518361. ISBN 9780231890526. OCLC 1205319295.

- Elayi, Josette (1997). "Pouvoirs locaux et organisation du territoire des cités phéniciennes sous l'Empire perse achéménide" [Local authorities and organization of the territory of the Phoenician cities under the Persian Achaemenid Empire]. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. 2, Historia antigua (in French). Editorial UNED. 10: 63–77. OCLC 758903288. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023.

- Elayi, Josette; Sapin, Jean (1998). Beyond the River: New Perspectives on Transeuphratene. Sheffield: Sheffield Academy Press. ISBN 9781850756781. OCLC 277560168.

- Elayi, Josette (2004). "La chronologie de la dynastie sidonienne d'Ešmun'azor" [The chronology of the Sidonian dynasty of Ešmun'azor]. Transeuphratène (in French). 27: 9–28.

- Elayi, Josette; Elayi, A. G. (2004). Le monnayage de la cité phénicienne de Sidon à l'époque perse (Ve-IVe s. av. J.-C.): Texte [The coinage of the Phoenician city of Sidon in the Persian era (V-IV s. av. J.-C.): Text] (in French). Paris: Gabalda. ISBN 9782850211584. OCLC 1135997515.

- Elayi, Josette (2006). "An updated chronology of the reigns of Phoenician kings during the Persian period (539–333 BCE)" (PDF). Transeuphratène. Paris: Gabalda. 32: 11–43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2023.

- Elayi, Josette (2018a). The history of Phoenicia. Translated by Plummer, Andrew. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. ISBN 9781937040826. LCCN 2017952621. OCLC 988170571.

- Elayi, Josette (2018b). Sennacherib, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 9780884143185. OCLC 1043306367.

- Gibson, John C. L. (1982). Textbook of Syrian Semitic inscriptions. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198131991. OCLC 997407167.

- Greenfield, Jonas C. (1985). "A group of Phoenician city seals". Israel Exploration Journal. 35 (2/3): 129–134. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27925980. OCLC 9973343267. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023 – via JSTOR.

- Haelewyck, Jean-Claude (2012). "The Phoenician inscription of Eshmunazar. An attempt at vocalization" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Académie Belge pour l'Étude des Langues Anciennes et Orientales: 77–98. doi:10.14428/BABELAO.VOL1.2012.19803. OCLC 1130515460. S2CID 191414877. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2023.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1967). Lebanon in history: from the earliest times to the present (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 612760.

- Hitzig, Ferdinand (1855). Die grabschrift des Eschmunazar [The epitaph of the Eschmunazar] (in German). Leipzig: S. Hirzel. OCLC 6750303.

- Jayne, Walter Addison (2003). Healing gods of ancient civilizations. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9780766176713. OCLC 54357727.

- Jean, Charles François (1947). "L'étude du milieu biblique" [The study of the biblical environment]. Nouvelle Revue Théologique (in French). 3 (69): 245–270. OCLC 1010046436. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- Jidéjian, Nina (2000). "Greater Sidon and its "Cities of the Dead"" (PDF). Archaeology & History in Lebanon. Ministère de la Culture – Direction Générale des Antiquités (Liban) (10): 15–24. OCLC 1136088978. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2021 – via AHL (Archaeology & History in Lebanon).

- Jidejian, Nina; Dunand, Maurice (2006). Sidon Through the Ages. Mansourieh (Lebanon): Aleph. ISBN 9789953008400. OCLC 643139133.

- Journal of Commerce staff (1856). "A voice from the ancient dead: Who shall interpret it?". United States magazine of science, art, manufactures, agriculture, commerce and trade. New York, N.Y.: J.M. Emerson & Company. pp. 379–381.

- Kaoukabani, Ibrahim (2005). "Les estampilles phénicienne de Tyr" [The Phoenician stamps of Tyre] (PDF). Archaeology & History in the Lebanon (in French). AHL (21): 3–79. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2023 – via Archaeology & History in Lebanon.

- Katzenstein, H. Jacob (1979). "Tyre in the Early Persian Period (539–486 B.C.E.)". The Biblical Archaeologist. 42 (1): 23–34. doi:10.2307/3209545. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209545. OCLC 5546242068. S2CID 165757132. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023.

- Kelly, Thomas (1987). "Herodotus and the chronology of the kings of Sidon". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (268): 39–56. doi:10.2307/1356993. JSTOR 1356993. S2CID 163208310.

- King, James (1887). "The Saida discoveries" (PDF). The Churchman. Hartford, Conn.: George S. Mallory. 2: 134–144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2021.

- King, Karen L. (1997). Women and goddess traditions: In antiquity and today. Studies in antiquity and Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800629199. OCLC 36892861.

- Kessler, Peter (10 May 2020) [2020]. "Kingdoms of the Levant – Sidon". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Kessler Associates. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Klat, Michel G. (2002). "The Durighello family" (PDF). Archaeology & History in Lebanon. London: Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum (16): 98–108. OCLC 1136119280. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2021.

- Levy, Moritz Abraham (1864). Phonizisches Worterbuch [Phoenician dictionary] (in German). Breslau: Schletter. OCLC 612905.

- duc de Luynes, Honoré Théodoric Paul Joseph d'Albert (1856). Mémoire sur le Sarcophage et inscription funéraire d'Esmunazar, roi de Sidon [Memoire on the sarcophagus and funeral inscription of Esmunazar, King of Sidon]. Paris: Henri Plon. OCLC 7065087. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021 – via Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Mariette, Auguste (1856). Choix de monuments et de dessins découverts ou exécutés pendant le déblaiement du Sérapéum de Memphis [Selection of monuments and drawings discovered or executed during the clearing of the Memphis Serapeum] (in French). Paris: Gide et J. Baudry. OCLC 1177767435.

- Munk, Salomon (1856). Essais sur l'inscription phénicienne du sarcophage d'Eschmoun-'Ezer, roi de Sidon: Mit 1 Tafel (Extr. no 5 de l'année 1856 du j. as.) [Essays on the Phoenician inscription of the sarcophagus of Eschmoun – ' Ezer, King of Sidon: Mit 1 Tafel (Extr. No. 5 of the year 1856 of J. as.)] (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Impériale. OCLC 163001695.

- Nabulsi, Rachel (2017). "Chapter 8: Phoenician funerary inscriptions". Death and burial in Iron Age Israel, Aram, and Phoenicia. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 299–320. doi:10.31826/9781463237240-011. ISBN 9781463237240. OCLC 1100435880.

- Netanyahu, Benzion (1964). The world history of the Jewish people. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813506159. OCLC 38731202.

- Nitschke, Jessica Lynn Nager (2007). Perceptions of culture: Interpreting Greco -Near Eastern hybridity in the Phoenician homeland (Thesis). OCLC 892834518. ProQuest 304900906.

- Perrot, Georges; Chipiez, Charles (1885). History of art in Phœnicia and its dependencies. Translated by Armstrong, Walter. London: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 2721474.

- Pritchard, James B.; Fleming, Daniel E. (2011). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691147260.

- Sennachérib (2012). Grayson, Albert Kirk; Novotny, Jamie Robert (eds.). The royal inscriptions of Sennacherib, king of Assyria (704-681 BC). The royal inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian period. Winona Lake (Indiana): Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575062419. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- Tahan, Lina G. (2017). "Trafficked Lebanese antiquities: can they be repatriated from European museums?". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 5 (1): 27–35. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027. S2CID 164865577. Project MUSE 649730. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022.

- Turner, William W. (1860). "Remarks on the Phœnician inscription of Sidon". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 7: 48–59. doi:10.2307/592156. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 592156. OCLC 6015459165.

- Versluys, Miguel John (2011). "Understanding Egypt in Egypt and beyond". Isis on the Nile. Egyptian gods in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt. Leiden: Brill. pp. 7–36. doi:10.1163/EJ.9789004188822.I-364.10. ISBN 9789004188822. OCLC 6066955064.

- Wilson, Sir Charles William (1982) [1880]. Lebanon & the North (Reprinted from the book originally published in 1880 under title: Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt ed.). Jerusalem: Ariel Publishing House.

- Xella, Paolo; López, José-Ángel Zamora (2005b). "Nouveaux documents phéniciens du sanctuaire d'Eshmoun à Bustan esh-Sheikh (Sidon)" [New Phoenician documents from the sanctuary of Eshmun in Bustan esh-Sheikh (Sidon)]. In Arruda, A. M. (ed.). Atti del VI congresso internazionale di studi Fenici e Punici [Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Phoenician and Punic studies] (in French). Lisbon.

- Yates, Kyle Monroe (1942). Preaching from the Prophets. New York: Harper & brothers. ISBN 9780805415025.

- Zamora, José-Ángel (2016). "Autres rois, autre temple: la dynastie d'Eshmounazor et le sanctuaire extra-urbain de Eshmoun à Sidon" [Other kings, other temple: the dynasty of Eshmunazor and the extra-urban sanctuary of Eshmun in Sidon]. In Russo Tagliente, Alfonsina; Guarneri, Francesca (eds.). Santuari mediterranei tra Oriente e Occidente : interazioni e contatti culturali : atti del Convegno internazionale, Civitavecchia – Roma 2014 [Mediterranean sanctuaries between East and West: interactions and cultural contacts: Proceedings of the International Conference, Civitavecchia–Rome 2014] (in French). Rome: Scienze e lettere. pp. 253–262. ISBN 9788866870975.

- "Le Sarcophage d'un Roi de Sidon". Revue Archéologique. 12 (2): 431–434. 1855. JSTOR 41746290.