Weapons in science fiction

Strange and exotic weapons are a recurring feature in science fiction. In some cases, weapons first introduced in science fiction have been made a reality; other science-fiction weapons remain purely fictional, and are often beyond the realms of known physical possibility.

At its most prosaic, science fiction features an endless variety of sidearms—mostly variations on real weapons such as guns and swords. Among the best-known of these are the phaser—used in the Star Trek television series, films, and novels—and the lightsaber and blaster—featured in Star Wars movies, comics, novels, and TV shows.

Besides adding action and entertainment value, weaponry in science fiction sometimes touches on deeper concerns and becomes a theme, often motivated by contemporary issues. One example is science fiction that deals with weapons of mass destruction.

In early science fiction

Weapons of early science-fiction novels were usually bigger and better versions of conventional weapons, effectively more advanced methods of delivering explosives to a target. Examples of such weapons include Jules Verne's "fulgurator" and the "glass arrow" of the Comte de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam.[1]

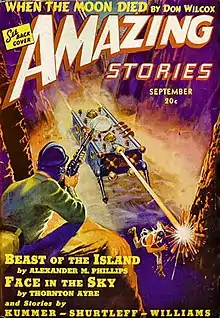

A classic science-fiction weapon, particularly in British and American science-fiction novels and films, is the raygun. A very early example of a raygun is the Heat-Ray featured in H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds (1898).[2][3]

The discovery of X-rays and radioactivity in the last years of the 19th century led to an increase in the popularity of this family of weapons, with numerous examples in the early 20th century, such as the disintegrator rays of George Griffith's future-war novel The Lord of Labour (1911).[1] Early science-fiction film often showed raygun beams making bright light and loud noise like lightning or large electric arcs.

Wells also prefigured modern armored warfare with his description of tanks in his 1903 short story "The Land Ironclads", and aerial warfare in his 1907 novel The War in the Air.

Lasers and particle beams

Arthur C. Clarke envisaged particle beam weapons in his 1955 novel Earthlight, in which energy would be delivered by high-velocity beams of matter.[4]

After the invention of the laser in 1960, it briefly became the death ray of choice for science-fiction writers. For instance, characters in the Star Trek pilot episode The Cage (1964) and in the Lost in Space TV series (1965–1968) carried handheld laser weapons.[5]

By the late 1960s and 1970s, as the laser's limits as a weapon became evident, the raygun began to be replaced by similar weapons with names that better reflected the destructive capabilities of the device. These names ranged from the generic "pulse rifle" to series-specific weapons, such as the phasers from Star Trek.

In the Warhammer 40,000 franchise, a human faction known as the Imperial Guard has a "lasgun", which is described as being a handheld laser weapon, as their main weapon, and larger cannon versions being mounted onto tanks and being carried around by Space Marines. The elf-like Aeldari, meanwhile, have a special unit called the Swooping Hawks equipped with a "lasblaster".

In the Command & Conquer video game series, various factions make extensive use of laser and particle-beam technology. The most notable are Allied units Prism Tank from Red Alert 2 and Athena Cannon from Red Alert 3, the Nod's Avatar and Obelisk of Light from Tiberium Wars, as well as various units from Generals constructed by USA faction, including their "superweapon" particle cannon.

Plasma weaponry

Weapons using plasma (high-energy ionized gas) have been featured in a number of fictional universes.

Weapons of mass destruction

Nuclear weapons are a staple element in science-fiction novels. The phrase "atomic bomb" predates their existence, and dates back to H. G. Wells' The World Set Free (1914), when scientists had discovered that radioactive decay implied potentially limitless energy locked inside of atomic particles (Wells' atomic bombs were only as powerful as conventional explosives, but would continue exploding for days on end). Cleve Cartmill predicted a chain reaction-type nuclear bomb in his 1944 science-fiction story "Deadline", which led to the FBI investigating him, due to concern over a potential breach of security on the Manhattan Project.[6]

The use of radiological, biological, and chemical weapons is another common theme in science fiction. In the aftermath of World War I, the use of chemical weapons, particularly poison gas, was a major worry, and was often employed in the science fiction of this period, for example Neil Bell's The Gas War of 1940 (1931).[1] Robert A. Heinlein's 1940 story "Solution Unsatisfactory" posits radioactive dust as a weapon that the US develops in a crash program to end World War II; the dust's existence forces drastic changes in the postwar world. In The Dalek Invasion of Earth, set in the 22nd century, Daleks are claimed to have invaded Earth after it was bombarded with meteorites and a plague wiped out entire continents.

A subgenre of science fiction, postapocalyptic fiction, uses the aftermath of nuclear or biological warfare as its setting.

The Death Star is the Star Wars equivalent to a weapon of mass destruction, and as such, might be the most well-known weapon of mass destruction in science fiction.

Powered armor and fighting suits

The idea of powered armor has appeared in a wide variety of fiction, beginning with E. E. Smith's Lensman series in 1937. One of the most famous early versions was Heinlein's 1959 novel Starship Troopers, which can be seen as spawning the entire subgenre concept of military "powered armor", which would be further developed in Joe Haldeman's The Forever War. The Marvel character Iron Man is another noteworthy example. Other examples include the power armor used by the Space Marines and other characters from Games Workshop's Warhammer 40k franchise, and the power armor used by the Brotherhood of Steel in the Fallout franchise, and the MJOLNIR Armor worn by protagonist Master Chief in the Halo series of video games. The anime series Gundam centers around giant piloted suits of armor called Mobile Suits.

Powered armor suits appear numerous times in the later Command and Conquer games. The Terrans, a future version of humanity in the StarCraft series, are often seen in powered combat suits and equipped with rifles that fire bullets similar to a tip of a pencil. Others are equipped with the a sort of cybernetic implant.

Some science-fiction stories contain accounts of hand-to-hand combat in zero gravity, and the idea that old-fashioned edged weapons—daggers, saws, mechanical cutters—may still have the advantage in close-up situations where projectile weapons are impractical.

Cyberwarfare and cyberweapons

The idea of cyberwarfare, in which wars are fought within the structures of communication systems and computers using software and information as weapons, was first explored by science fiction.

John Brunner's 1975 novel The Shockwave Rider is notable for coining the word "worm" to describe a computer program that propagates itself through a computer network, used as a weapon in the novel.[7][8] William Gibson's Neuromancer coined the phrase cyberspace, a virtual battleground in which battles are fought using software weapons and counterweapons. The Star Trek episode "A Taste of Armageddon" is another notable example.

Certain Dale Brown novels place cyberweapons in different roles. The first is the "netrusion" technology used by the U.S. Air Force. It sends corrupt data to oncoming missiles to shut them down, as well as hostile aircraft by giving them a "shutdown" order in which the systems turn off one by one. It is also used to send false messages to hostiles, to place the tide of battle in the favor of America. The technology is later reverse-engineered by the Russian Federation to shut down American antiballistic missile satellites from a tracking station at Socotra Island, Yemen.

Cyberwarfare has moved from a theoretical idea to something that is now seriously considered as a threat by modern states.

In a similar but unrelated series of incidents involved various groups of hackers from India and Pakistan who hacked and defaced several websites of companies and government organizations based in each other's country. The actions were committed by various groups based in both countries, but not known to be affiliated with the governments of India or Pakistan. The cyber wars are believed to have begun in 2008 following the Mumbai attacks believed to be by a group of Indian cyber groups hacking into Pakistani websites. Hours after the cyber attacks, a number of Indian websites (both government and private) were attacked by groups of Pakistani hackers, claiming to be retaliation for Indian attacks on Pakistani websites.[9] The back and forth attacks have persisted on occasions since then.[10]

Doomsday machines

A doomsday machine is a hypothetical construction that could destroy all life, either on Earth or beyond, generally as part of a policy of mutually assured destruction.

In Fred Saberhagen's 1967 Berserker stories, the Berserkers of the title are giant computerized self-replicating spacecraft, once used as a doomsday device in an interstellar war aeons ago, and having destroyed both their enemies and their makers, are still attempting to fulfil their mission of destroying all life in the universe. The 1967 Star Trek episode "The Doomsday Machine"[11] written by Norman Spinrad, explores a similar theme.

Alien doomsday machines are common in science fiction as "Big Dumb Objects", McGuffins around which the plot can be constructed. An example is the Halo megastructures in the video game franchise Halo, which are a system of world-sized doomsday machines that when fired simultaneously will eliminate all sentient life in three radii of the galactic center, with each one having a maximum effective range of 25,000 light-years in every direction.

The sentient weapon

The science-fiction themes of autonomous weapons systems and the use of computers in warfare date back to the 1960s, often in a frankensteinian context, notably in Harlan Ellison's 1967 short story "I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream" and films such as The Forbin Project, originally released in 1970 (based on a novel by Dennis Feltham Jones). In Keith Laumer's Bolo novels, the eponymous protagonists are huge main battle tanks with self-aware artificial intelligence.

Another common theme is that of dehumanised, cyborg or android soldiers: human, or quasi-human beings who are themselves weapons. Philip K. Dick's 1953 short story "Second Variety" features self-replicating robot weapons, this time with the added theme of weapons imitating humans. In his short story "Impostor", Dick goes one step further, making its protagonist a manlike robot bomb that actually believes itself to be a human being.

The idea of robot killing machines disguised as humans is central to James Cameron's film The Terminator, and its subsequent media franchise. They also appear as the central problem of the 1995 cult film Screamers (based on "Second Variety") and its sequel. The Battlestar Galactica's cylons are sentient weapons, too, even in the original series and in its reboot in the 2000s. However, human-looking cylons are the central characters of the remake series (in the original series, only one prototype was human-looking).

In Harlan Ellison's 1957 short story "Soldier From Tomorrow", the protagonist is a soldier who has been conditioned from birth by the State solely to fight and kill the enemy. Samuel R. Delany's 1966 novella "Babel-17" features TW-55, a purpose-grown cloned assassin. Ridley Scott's 1982 film Blade Runner, like Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, on which it is loosely based, uses the story of a hunt for escaped military androids to explore the idea what it means to be human.

In John Carpenter's 1974 film Dark Star, a notable portion of the plot involves the characters trying to convince a large, intelligent bomb not to detonate inside the ship.

The idea of animated weapons is now so much a science-fiction trope that it has spawned a whole genre of science-fiction films such as Hardware, Death Machine, and Universal Soldier.

War on the mind

Themes of brainwashing, conditioning, memory-erasing, and other mind-control methods as weapons of war feature in much science fiction of the late 1950s and 1960s, paralleling the contemporary panic about communist brainwashing, existence of sleeper agents, and the real-world attempts of governments in programs such as MK-ULTRA to make such things real.

David Langford's short story "BLIT" (1988) posits the existence of images (called "basilisks") that are destructive to the human brain, which are used as weapons of terror by posting copies of them in areas where they are likely to be seen by the intended victims. Langford revisited the idea in a fictional FAQ on the images, published by the science journal Nature in 1999.[12][13] The neuralyzer from the Men in Black films are compact objects that can erase and modify the short-term memories of witnesses by the means of a brief flash of light, ensuring that no one remembers encountering either aliens or the agents themselves.

The TV series Dollhouse (2009) features technology that can "mindwipe" people (transforming them into "actives", or "dolls") and replace their inherent personalities with another one, either "real" (from another actual person's mind), fabricated (for example, a soldier trained in many styles of combat and weaponry, or unable to feel pain), or a mixture of both. In a future timeline of the series, the technology has been devised into a mass weapon, able to "remote wipe" anyone and replace them with any personality. A war erupts between those controlling actives, and "actuals" (a term to describe those still retaining their original personas). An offshoot technology allows actual people to upload upgrades to their personas (such as fighting or language skills), similar to the process seen in The Matrix, albeit for only one skill at a time.

Biological weapons

Biological weapons and bioterrorism have appeared in many science-fiction works, arguably dating back to The War of the Worlds (1897), in which the invading Martians are ultimately defeated by infection from Earth bacteria. In the dystopian film V for Vendetta, the fascist government of Britain causes a plague for which it has the only antidote, to ensure complete takeover of the country. In two books in the Animorphs series, The Hork-Bajir Chronicles and The Arrival, engineered viruses are created by an alien species to cause massive casualties against their enemies. Similarly, a biological virus is created by the Draka in the novel The Stone Dogs. A manufactured virus is responsible for turning humans into zombies in the Resident Evil video game series.

Resizeability

.jpg.webp)

Some weapons in science fiction can be folded and put away for easy storage. For instance, the sword carried by Hikaru Sulu in the Star Trek movie of 2009 had its blade unfold from its own form into the fully extended position from the state of a simple handle. Another example of this are the weapons of the Mass Effect universe. The weaponry in the games could fold up into smaller and more compact shapes when holstered or deactivated. Lightsabers from Star Wars are no larger than a flashlight until they are turned on. In the 1980's Transformers animated series several of the Autobots and Decepticons shrink or enlarge to the size of the vehicle, weapon, or object they copied or to a size permitting transport of another Transformer or used as a weapon (Megatron shrank to a "normal" handgun or to a weapon sized for a Transformer the same size to wield.

Parallels between science-fiction and real-world weapons

Some new forms of real-world weaponry resemble weapons previously envisaged in science fiction. The early 1980s-era Strategic Defense Initiative, a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (Intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles), gained the popular name "Star Wars" after the popular franchise created by George Lucas.[14]

In some cases, the influence of science fiction on weapons programs has been specifically acknowledged. In 2007, science-fiction author Thomas Easton was invited to address engineers working on a DARPA program to create weaponized cyborg insects, as envisaged in his novel Sparrowhawk. [15]

Active research on powered exoskeletons for military use has a long history, beginning with the abortive 1960s Hardiman powered exoskeleton project at General Electric,[16] and continuing into the 21st century.[17] The borrowing between fiction and reality has worked both ways, with the power loader from the film Aliens resembling the prototypes of the Hardiman system.[18]

American military research on high-power laser weapons started in the 1960s, and has continued to the present day,[19] with the U.S. Army planning, as of 2008, the deployment of practical battlefield laser weapons.[20] Lower-powered lasers are currently used for military purposes as laser target designators and for military rangefinding. Laser weapons intended to blind combatants have also been developed, but are currently banned by the Protocol on Blinding Laser Weapons, although low-power versions designed to dazzle rather than blind have been developed experimentally. Gun-mounted lasers have also been used as psychological weapons, to let opponents know that they have been targeted to encourage them to hide or flee without having to actually open fire on them.[21][22]

See also

References

- Stableford, Brian (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. CRC Press. pp. 563–565. ISBN 0-415-97460-7.

- "The rise of the ray-gun: Fighting with photons". The Economist. October 30, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Van Riper, op.cit., p. 46.

- "Science fiction inspires DARPA weapon". April 22, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Van Riper, A. Bowdoin (2002). Science in popular culture: a reference guide. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 45. ISBN 0-313-31822-0.

- "Reflections: The Cleve Cartmill Affair" by Robert Silverberg

- Ravo, Nick; Nash, Eric (August 8, 1993). "The Evolution of Cyberpunk". New York Times.

- Craig E. Engler (1997). "Classic Sci-Fi Reviews: The Shockwave Rider". Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- "India and Pakistan in cyber war".

- "Cyber warfare: Pakistani hackers claim defacing over 2,000 Indian websites". The Express Tribune. February 2, 2014.

- "Star Trek Doomsday Machine, The". StarTrek.com.

- BLIT, David Langford, Interzone, 1988.

- comp.basilisk FAQ, David Langford, "Futures," Nature, December 1999.

- Sharon Watkins Lang. SMDC/ASTRAT Historical Office. Where do we get "Star Wars"?. The Eagle. March 2007. Archived April 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Darpa hatches plan for insect cyborgs to fly reconnaissance". EEtimes. February 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- "Hardiman". Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- John Jansen, Brad Richardson, Francois Pin, Randy Lind and Joe Birdwell (September 2000). "Exoskeleton for Soldier Enhancement Systems Feasibility Study" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dyer, Owen (August 3, 2001). "Meet the army's newest recruit". London: The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- Rincon, Paul (February 22, 2007). "Record power for military laser". BBC News. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- "Army Moves Ahead With Mobile Laser Cannon". Wired. August 19, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- "US military sets laser PHASRs to stun". New Scientist. November 7, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- "New Laser Technologies for Infantry Warfare, Counterinsurgency Ops, and LE Apps". defensereview.com. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

Further reading

- David Seed. American Science Fiction and the Cold War: literature and film ISBN 1-85331-227-4

- John Hamilton. Weapons of Science Fiction ISBN 1-59679-997-8

- Westfahl, Gary (2022). "Weapons—Fifty Ways to Kill Your Lover: The Weapons of Science Fiction". The Stuff of Science Fiction: Hardware, Settings, Characters. McFarland. pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-1-4766-8659-2.