Born in the purple

Traditionally, born in the purple[1] (sometimes "born to the purple") was a category of members of royal families born during the reign of their parent. This notion was later loosely expanded to include all children born of prominent or high-ranking parents.[2] The parents must be prominent at the time of the child's birth so that the child is always in the spotlight and destined for a prominent role in life. A child born before the parents become prominent would not be "born in the purple". This color purple came to refer to Tyrian purple, restricted by law, custom, and the expense of creating it to royalty.

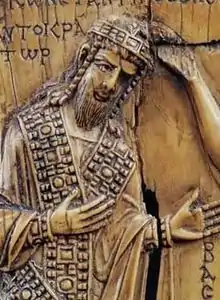

Porphyrogénnētos (Greek: Πορφυρογέννητος, lit. 'purple-born'), Latinized as Porphyrogenitus, was an honorific title in the Byzantine Empire given to a son, or daughter (Πορφυρογέννητη, Porphyrogénnētē, Latinized Porphyrogenita), born after the father had become emperor.[3]

Both imperial or Tyrian purple, a dye for cloth, and the purple stone porphyry were rare and expensive, and at times reserved for imperial use. In particular there was a room in the imperial Great Palace of Constantinople entirely lined with porphyry, where reigning empresses gave birth.

Porphyrogeniture

Porphyrogeniture is a system of political succession that favours the rights of sons born after their father has become king or emperor, over older siblings born before their father's ascent to the throne.

Examples of this practice include Byzantium and the Nupe Kingdom.[4]: 33 In late 11th century England and Normandy, the theory of porphyrogeniture was used by Henry I of England to justify why he, and not his older brother Robert Curthose, should inherit the throne after the death of their brother William Rufus.[5]: 105

The concept of porphyrogénnētos (literally meaning "born in the purple") was known from the sixth century in connection with growing ideas of hereditary legitimacy, but the first secure use of the word is not found until 846.[3] The term became common by the 10th century, particularly in connection with Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (r. 913–959), and its use continued into the Palaiologan period.[3] Constantine VII described the ceremonies which took place during the birth of a porphyrogénnētos boy in his work De Ceremoniis aulae byzantinae.[3]

Etymology

.JPG.webp)

The Byzantines themselves ascribed it either to the fact that the child was born to parents bearing the imperial purple, or because the child was born in a special porphyry chamber in the Great Palace of Constantinople.[3] As the porphyrogennētē 12th-century princess Anna Komnene described it, the room, "set apart long ago for an empress's confinement", was located "where the stone oxen and the lions stand" (i.e. the Boukoleon Palace), and was in the form of a perfect square from floor to ceiling, with the latter ending in a pyramid. Its walls, floor and ceiling were completely veneered with imperial porphyry, which was "generally of a purple colour throughout, but with white spots like sand sprinkled over it."[6] However, both explanations were current already in the 10th century.[3]

Imperial purple was a luxury dye obtained from sea snails, used to colour cloth. Its production was extremely expensive, so the dye was used as a status symbol by the Ancient Romans, e.g. a purple stripe on the togas of Roman magistrates. By the Byzantine period the colour had become associated with the emperors, and sumptuary laws restricted its use by anyone except the imperial household. Purple was thus seen as an imperial colour.

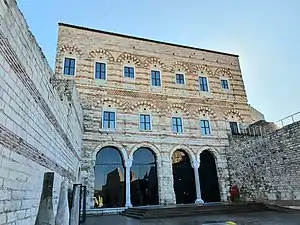

The Palace of the Porphyrogenitus is a late 13th-century Byzantine palace in the north-western part of the old city of Constantinople named after Constantine Palaiologos, a younger son of Emperor Michael VIII.

Diplomacy

In Imperial diplomacy a porphyrogénnēta bride was sometimes sent to seal a bargain, or a foreign princess may have gone to Constantinople to marry a porphyrogénnētos. Liutprand of Cremona, for instance, visited Constantinople in 968 on a diplomatic mission from Otto I to secure a purple-born bride for the prince who would eventually become Otto II, in which mission he failed.[7] A different bride who was not purple-born, Theophanu, was subsequently acquired in 971.[8]

Limitations

To be "born in the purple" is often seen as a limitation to be escaped rather than a benefit or a blessing.[9] Rarely, the term refers to someone born with immense talent that shapes their career and forces them into paths they might not otherwise wish to follow. An obituary of the British composer Hubert Parry complains that his immense natural talent (described as being "born in the purple") forced him to take on teaching and administrative duties that prevented him from composing in the manner that might have been allowed to someone who had to develop their talent.[10]

In this sense, the parents' prominence predetermines the child's role in life. A royal child, for instance, is denied the opportunity to an ordinary life because of his parents' royal rank.[11] An example of this usage can be seen in the following discussion comparing the German Kaiser Wilhelm II with his grandfather, Wilhelm I, and his father, Frederick III:

Compare this with his grandfather, the old Emperor, who, if he had not been born in the purple, could only have been a soldier, and not, it must be added, one who could have held very high commands. Compare him again with his father; the Emperor Frederick, if he had not been born in the purple, though he certainly showed greater military capacity than the old Emperor, nevertheless would probably not have been happy or successful in any private station other than that of a great moral teacher.[11]

The classic definition restricted use of the category specifically to the legitimate offspring born to reigning monarchs after they ascended to the throne.[12] It did not include children born prior to their parents' accession or, in an extremely strict definition, their coronation.[13]

See also

References

- "Purple". Webster's Dictionary. 1913. Archived from the original on February 22, 2006. Retrieved 2008-10-19. At the bottom of the first definition of the word "purple."

- "Purple". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1) based on Random House Unabridged Dictionary. 1996. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- McCormick, M. (1991). "Porphyrogennetos". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1701. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Goody, Jack (1979). "Introduction". In Goody, Jack (ed.). Succession to High Office. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–56. ISBN 9780521297325.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2003). Henry I. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300098297.

- Comnena, Anna (2003), The Alexiad, London: Penguin, pp. 196, 219, ISBN 0-14-044958-2.

- "Liudprand of Cremona - a diplomat?" by Constanze M.F. Schummer in Shepard J. & Franklin, Simon. (Eds.) (1992) Byzantine Diplomacy: Papers from the Twenty-fourth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Cambridge, March 1990. Aldershot: Variorum, p. 197.

- "LIUTPRAND OF CREMONA" in The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 1241. ISBN 0195046528

- "Dom Pedro and Brazil" (PDF). The New York Times. 1891. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Legge, Robin H. "Charles Hubert Hastings Parry". The Musical Times. 1918. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Anonymous, "The Empress Frederick, A Memoir". James Nesbit and Company, London. 1913. Archived from the original on 2002-11-16. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- "Born in the Purple". in E. Cobham Brewer, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. 1898. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- "The Unfading Light Of Charity Grand Duchess Olga As A Philanthropist And Painter". Historical Magazine: Gatchina Through The Centuries. 2004. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

Further reading

- Gilbert, Paul. Born in the Purple: The Private World of the Children of Tsar Nicholas II, (hardcover, ISBN 0-9737839-5-8). Biography of the children of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia who were all born after his accession.

- Jensen, Lloyd B. (April 1963). "Royal Purple of Tyre". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 22 (2): 104–118. doi:10.1086/371717. JSTOR 543305. S2CID 161424526.