History of Cambodia

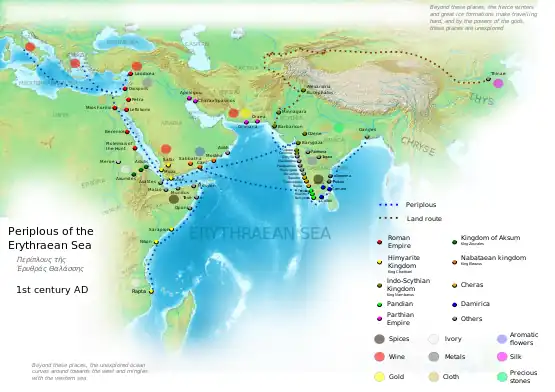

The history of Cambodia, a country in mainland Southeast Asia, can be traced back to Indian civilization.[1][2] Detailed records of a political structure on the territory of what is now Cambodia first appear in Chinese annals in reference to Funan, a polity that encompassed the southernmost part of the Indochinese peninsula during the 1st to 6th centuries. Centered at the lower Mekong,[3] Funan is noted as the oldest regional Hindu culture, which suggests prolonged socio-economic interaction with maritime trading partners of the Indosphere in the west.[4] By the 6th century a civilization, called Chenla or Zhenla in Chinese annals, firmly replaced Funan, as it controlled larger, more undulating areas of Indochina and maintained more than a singular centre of power.[5][6]

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor Period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

The Khmer Empire was established by the early 9th century. Sources refer here to a mythical initiation and consecration ceremony to claim political legitimacy by founder Jayavarman II at Mount Kulen (Mount Mahendra) in 802 CE.[7] A succession of powerful sovereigns, continuing the Hindu devaraja cult tradition, reigned over the classical era of Khmer civilization until the 11th century. A new dynasty of provincial origin introduced Buddhism, which according to some scholars resulted in royal religious discontinuities and general decline.[8] The royal chronology ends in the 14th century. Great achievements in administration, agriculture, architecture, hydrology, logistics, urban planning and the arts are testimony to a creative and progressive civilisation - in its complexity a cornerstone of Southeast Asian cultural legacy.[9]

The decline continued through a transitional period of approximately 100 years followed by the Middle Period of Cambodian history, also called the Post-Angkor Period, beginning in the mid 15th century. Although the Hindu cults had by then been all but replaced, the monument sites at the old capital remained an important spiritual centre.[10] Yet since the mid 15th century the core population steadily moved to the east and – with brief exceptions – settled at the confluence of the Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers at Chaktomuk, Longvek and Oudong.[11][12]

Maritime trade was the basis for a very prosperous 16th century. But, as a result foreigners – Muslim Malays and Cham, Christian European adventurers and missionaries – increasingly disturbed and influenced government affairs. Ambiguous fortunes, a robust economy on the one hand and a disturbed culture and compromised royalty on the other were constant features of the Longvek era.[13][14]

By the 15th century, the Khmers' traditional neighbours, the Mon people in the west and the Cham people in the east had gradually been pushed aside or replaced by the resilient Siamese/Thai and Annamese/Vietnamese, respectively.[15] These powers had perceived, understood and increasingly followed the imperative of controlling the lower Mekong basin as the key to control all Indochina. A weak Khmer kingdom only encouraged the strategists in Ayutthaya (later in Bangkok) and in Huế. Attacks on and conquests of Khmer royal residences left sovereigns without a ceremonial and legitimate power base.[16][17] Interference in succession and marriage policies added to the decay of royal prestige. Oudong was established in 1601 as the last royal residence of the Middle Period.[18]

The 19th-century arrival of then technologically more advanced and ambitious European colonial powers with concrete policies of global control put an end to regional feuds and as Siam/Thailand, although humiliated and on the retreat, escaped colonisation as a buffer state, Vietnam was to be the focal point of French colonial ambition.[19] [20] Cambodia, although largely neglected,[21] had entered the Indochinese Union as a perceived entity and was capable to carry and reclaim its identity and integrity into modernity.[22][23]

After 80 years of colonial hibernation, the brief episode of Japanese occupation during World War II, that coincided with the investiture of king Sihanouk was the opening act[24] for the irreversible process towards re-emancipation and modern Cambodian history. The Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–70), independent since 1953, struggled to remain neutral in a world shaped by polarisation of the nuclear powers USA and Soviet Union.[25] As the Indochinese war escalated, and Cambodia became increasingly involved,[26] the Khmer Republic resulted in 1970. Another result was a civil war which by 1975, ended with the takeover by the Khmer Rouge. Cambodia endured its darkest hour – Democratic Kampuchea[15] and the long aftermath of Vietnamese occupation, the People's Republic of Kampuchea and the UN Mandate towards Modern Cambodia since 1993.[27]

Prehistory and early history

Radiocarbon dating of a cave at Laang Spean in Battambang Province, northwest Cambodia confirmed the presence of Hoabinhian stone tools from 6000–7000 BCE and pottery from 4200 BCE.[28][29] Starting in 2009 archaeological research of the Franco-Cambodian Prehistoric Mission has documented a complete cultural sequence from 71.000 years BP to the Neolithic period in the cave.[30] Finds since 2012 lead to the common interpretation, that the cave contains the archaeological remains of a first occupation by hunter and gatherer groups, followed by Neolithic people with highly developed hunting strategies and stone tool making techniques, as well as highly artistic pottery making and design, and with elaborate social, cultural, symbolic and exequial practices.[31] Cambodia participated in the Maritime Jade Road, which was in place in the region for 3,000 years, beginning in 2000 BCE to 1000 CE.[32][33][34][35]

Skulls and human bones found at Samrong Sen in Kampong Chhnang Province date from 1500 BCE. Heng Sophady (2007) has drawn comparisons between Samrong Sen and the circular earthwork sites of eastern Cambodia. These people may have migrated from South-eastern China to the Indochinese Peninsula. Scholars trace the first cultivation of rice and the first bronze making in Southeast Asia to these people.[36]

2010 Examination of skeletal material from graves at Phum Snay in north-west Cambodia revealed an exceptionally high number of injuries, especially to the head, likely to have been caused by interpersonal violence. The graves also contain a quantity of swords and other offensive weapons used in conflict.[37]

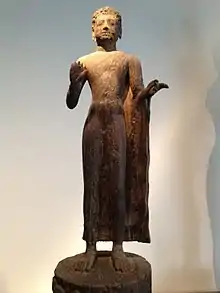

The Iron Age period of Southeast Asia begins around 500 BCE and lasts until the end of the Funan era - around 500 A.D. as it provides the first concrete evidence for sustained maritime trade and socio-political interaction with India and South Asia. By the 1st century settlers have developed complex, organised societies and a varied religious cosmology, that required advanced spoken languages very much related to those of the present day. The most advanced groups lived along the coast and in the lower Mekong River valley and the delta regions in houses on stilts where they cultivated rice, fished and kept domesticated animals.[3][38][39][40]

Funan Kingdom (1st century – 550/627)

Chinese annals[41] contain detailed records of the first known organised polity, the Kingdom of Funan, on Cambodian and Vietnamese territory characterised by "high population and urban centers, the production of surplus food...socio-political stratification [and] legitimized by Indian religious ideologies".[42][43] Centered around the lower Mekong and Bassac rivers from the first to sixth century CE with "walled and moated cities"[44] such as Angkor Borei in Takeo Province and Óc Eo in modern An Giang Province, Vietnam.

Early Funan was composed of loose communities, each with its own ruler, linked by a common culture and a shared economy of rice farming people in the hinterland and traders in the coastal towns, who were economically interdependent, as surplus rice production found its way to the ports.[45]

By the second century CE Funan controlled the strategic coastline of Indochina and the maritime trade routes. Cultural and religious ideas reached Funan via the Indian Ocean trade route. Trade with India had commenced well before 500 BCE as Sanskrit hadn't yet replaced Pali.[4] Funan's language has been determined as to have been an early form of Khmer and its written form was Sanskrit.[46]

In the period 245–250 CE dignitaries of the Chinese Kingdom of Wu visited the Funan city Vyadharapura.[47][48] Envoys Kang Tai and Zhu Ying defined Funan as to be a distinct Hindu culture.[49] Trade with China had begun after the southward expansion of the Han Dynasty, around the 2nd century BCE Effectively Funan "controlled strategic land routes in addition to coastal areas"[50] and occupied a prominent position as an "economic and administrative hub"[51][52] between The Indian Ocean trade network and China, collectively known as the Maritime Silk Road. Trade routes, that eventually ended in distant Rome are corroborated by Roman and Persian coins and artefacts, unearthed at archaeological sites of 2nd and 3rd century settlements.[3][53]

Funan is associated with myths, such as the Kattigara legend and the Khmer founding legend in which an Indian Brahman or prince named Preah Thaong in Khmer, Kaundinya in Sanskrit and Hun-t’ien in Chinese records marries the local ruler, a princess named Nagi Soma (Lieu-Ye in Chinese records), thus establishing the first Cambodian royal dynasty.[54]

Scholars debate as to how deep the narrative is rooted in actual events and on Kaundinya's origin and status.[55][56] A Chinese document, that underwent 4 alterations[57] and a 3rd-century epigraphic inscription of Champa are the contemporary sources.[58] Some scholars consider the story to be simply an allegory for the diffusion of Indic Hindu and Buddhist beliefs into ancient local cosmology and culture[59] whereas some historians dismiss it chronologically.[60]

Chinese annals report that Funan reached its territorial climax in the early 3rd century under the rule of king Fan Shih-man, extending as far south as Malaysia and as far west as Burma. A system of mercantilism in commercial monopolies was established. Exports ranged from forest products to precious metals and commodities such as gold, elephants, ivory, rhinoceros horn, kingfisher feathers, wild spices like cardamom, lacquer, hides and aromatic wood. Under Fan Shih-man Funan maintained a formidable fleet and was administered by an advanced bureaucracy, based on a "tribute-based economy, that produced a surplus which was used to support foreign traders along its coasts and ostensibly to launch expansionist missions to the west and south".[3]

Historians maintain contradicting ideas about Funan's political status and integrity.[61] Miriam T. Stark calls it simply Funan: [The]"notion of Fu Nan as an early "state"...has been built largely by historians using documentary and historical evidence" and Michael Vickery remarks: "Nevertheless, it is...unlikely that the several ports constituted a unified state, much less an 'empire'".[62] Other sources though, imply imperial status: "Vassal kingdoms spread to southern Vietnam in the east and to the Malay peninsula in the west"[63] and "Here we will look at two empires of this period...Funan and Srivijaya".[64]

The question of how Funan came to an end is in the face of almost universal scholarly conflict impossible to pin down. Chenla is the name of Funan's successor in Chinese annals, first appearing in 616/617 CE

...the fall of Funan was not the result of the shifting of maritime trade route from the Malay Peninsula route to the Strait of Malacca starting from the 5th century CE; rather, it suggests that the conquest of Funan by Zhenla was the exact reason for the shifting of maritime trade route in the 7th century CE....[65]

"As Funan was indeed in decline caused by shifts in Southeast Asian maritime trade routes, rulers had to seek new sources of wealth inland."[66]

"By the end of the fifth century, international trade through southeast Asia was almost entirely directed through the Strait of Malacca. Funan, from the point of view of this trade, had outlived its usefulness."[67]

"Nothing in the epigraphical record authorizes such interpretations; and the inscriptions which retrospectively bridge the so- called Funan-Chenla transition do not indicate a political break at all."

The archaeological approach to and interpretation of the entire early historic period is considered to be a decisive supplement for future research.[69] The "Lower Mekong Archaeological Project" focuses on the development of political complexity in this region during the early historic period. LOMAP survey results of 2003 to 2005, for example, have helped to determine that "...the region's importance continued unabated throughout the pre-Angkorian period...and that at least three [surveyed areas] bear Angkorian-period dates and suggest the continued importance of the delta."[3]

Chenla Kingdom (6th century – 802)

The History of the Chinese Sui dynasty contains records that a state called Chenla sent an embassy to China in 616 or 617 CE It says, that Chenla was a vassal of Funan, but under its ruler Citrasena-Mahendravarman conquered Funan and gained independence.[70]

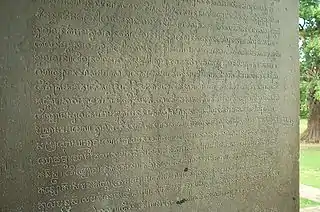

Most of the Chinese recordings on Chenla, including that of Chenla conquering Funan, have been contested since the 1970s as they are generally based on single remarks in the Chinese annals, as author Claude Jacques emphasised the very vague character of the Chinese terms 'Funan' and 'Chenla', while more domestic epigraphic sources become available. Claude Jacques summarises: "Very basic historical mistakes have been made" because "the history of pre-Angkorean Cambodia was reconstructed much more on the basis of Chinese records than on that of [Cambodian] inscriptions" and as new inscriptions were discovered, researchers "preferred to adjust the newly discovered facts to the initial outline rather than to call the Chinese reports into question".[71]

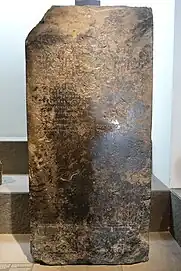

The notion of Chenla's centre being in modern Laos has also been contested. "All that is required is that it be inland from Funan."[72] The most important political record of pre-Angkor Cambodia, the inscription K53 from Ba Phnom, dated 667 CE does not indicate any political discontinuity, either in royal succession of kings Rudravarman, Bhavavarman I, Mahendravarman [Citrasena], Īśānavarman, and Jayavarman I or in the status of the family of officials who produced the inscription. Another inscription of a few years later, K44, 674 CE, commemorating a foundation in Kampot province under the patronage of Jayavarman I, refers to an earlier foundation in the time of King Raudravarma, presumably Rudravarman of Funan, and again there is no suggestion of political discontinuity.

The History of the T'ang asserts that shortly after 706 the country was split into Land Chenla and Water Chenla. The names signify a northern and a southern half, which may conveniently be referred to as Upper and Lower Chenla.[73]

By the late 8th century Water Chenla had become a vassal of the Sailendra dynasty of Java – the last of its kings were killed and the polity incorporated into the Javanese monarchy around 790 CE. Land Chenla acquired independence under Jayavarman II in 802 CE[74]

The Khmers, vassals of Funan, reached the Mekong river from the northern Menam River via the Mun River Valley. Chenla, their first independent state developed out of Funanese influence.[75]

Ancient Chinese records mention two kings, Shrutavarman and Shreshthavarman who ruled at the capital Shreshthapura located in modern-day southern Laos. The immense influence on the identity of Cambodia to come was wrought by the Khmer Kingdom of Bhavapura, in the modern day Cambodian city of Kampong Thom. Its legacy was its most important sovereign, Ishanavarman who completely conquered the kingdom of Funan during 612–628. He chose his new capital at the Sambor Prei Kuk, naming it Ishanapura.[76]

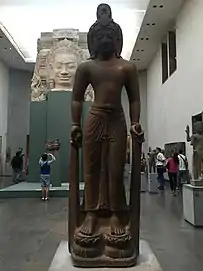

Khmer Empire (802–1431)

The six centuries of the Khmer Empire are characterised by unparalleled technical and artistic progress and achievements, political integrity and administrative stability. The empire represents the cultural and technical apogee of the Cambodian and Southeast Asian pre-industrial civilisation.[77]

.jpg.webp)

The Khmer Empire was preceded by Chenla, a polity with shifting centres of power, which was split into Land Chenla and Water Chenla in the early 8th century.[78] By the late 8th century Water Chenla was absorbed by the Malays of the Srivijaya Empire and the Javanese of the Shailandra Empire and eventually incorporated into Java and Srivijaya.[74] Jayavarman II, ruler of Land Chenla, initiates a mythical Hindu consecration ceremony at Mount Kulen (Mount Mahendra) in 802 CE, intended to proclaim political autonomy and royal legitimacy. As he declared himself devaraja - god-king, divinely appointed and uncontested, he simultaneously declares independence from Shailandra and Srivijaya. He established Hariharalaya, the first capital of the Angkorean area near the modern town of Roluos.[79]

Indravarman I (877–889) and his son and successor Yasovarman I (889–900), who established the capital Yasodharapura ordered the construction of huge water reservoirs (barays) north of the capital. The water management network depended on elaborate configurations of channels, ponds, and embankments built from huge quantities of clayey sand, the available bulk material on the Angkor plain. Dikes of the East Baray still exist today, which are more than 7 km (4 mi) long and 1.8 km (1 mi) wide. The largest component is the West Baray, a reservoir about 8 km (5 mi) long and 2 km (1 mi) across, containing approximately 50 million m3 of water.[80]

Royal administration was based on the religious idea of the Shivaite Hindu state and the central cult of the sovereign as warlord and protector – the "Varman". This centralised system of governance appointed royal functionaries to provinces. The Mahidharapura dynasty – its first king was Jayavarman VI (1080 to 1107), which originated west of the Dângrêk Mountains in the Mun river valley discontinued the old "ritual policy", genealogical traditions and crucially, Hinduism as exclusive state religion. Some historians relate the empires' decline to these religious discontinuities.[81][82]

The area that comprises the various capitals was spread out over around 1,000 km2 (386 sq mi), it is nowadays commonly called Angkor. The combination of sophisticated wet-rice agriculture, based on an engineered irrigation system and the Tonlé Sap's spectacular abundance in fish and aquatic fauna, as protein source guaranteed a regular food surplus. Recent Geo-surveys have confirmed that Angkor maintained the largest pre-industrial settlement complex worldwide during the 12th and 13th centuries – some three quarters of a million people lived there. Sizeable contingents of the public workforce were to be redirected to monument building and infrastructure maintenance. A growing number of researchers relates the progressive over-exploitation of the delicate local eco-system and its resources alongside large scale deforestation and resulting erosion to the empires' eventual decline.[83]

Under king Suryavarman II (1113–1150) the empire reached its greatest geographic extent as it directly or indirectly controlled Indochina, the Gulf of Thailand and large areas of northern maritime Southeast Asia. Suryavarman II commissioned the temple of Angkor Wat, built in a period of 37 years, its five towers representing Mount Meru is considered to be the most accomplished expression of classical Khmer architecture. However, territorial expansion ended when Suryavarman II was killed in battle attempting to invade Đại Việt. It was followed by a period of dynastic upheaval and a Cham invasion that culminated in the sack of Angkor in 1177.

King Jayavarman VII (reigned 1181–1219) is generally considered to be Cambodia's greatest King. A Mahayana Buddhist, he initiates his reign by striking back against Champa in a successful campaign. During his nearly forty years in power he becomes the most prolific monument builder, who establishes the city of Angkor Thom with its central temple the Bayon. Further outstanding works are attributed to him – Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Neak Pean and Sra Srang. The construction of an impressive number of utilitarian and secular projects and edifices, such as maintenance of the extensive road network of Suryavarman I, in particular the royal road to Phimai and the many rest houses, bridges and hospitals make Jayavarman VII unique among all imperial rulers.[84]

In August 1296, the Chinese diplomat Zhou Daguan arrived at Angkor and remained at the court of king Srindravarman until July 1297. He wrote a detailed report, The Customs of Cambodia, on life in Angkor. His portrayal is one of the most important sources of understanding historical Angkor as the text offers valuable information on the everyday life and the habits of the inhabitants of Angkor.[85]

The last Sanskrit inscription is dated 1327, and records the succession of Indrajayavarman by Jayavarman IX Parameshwara (1327–1336).

The empire was an agrarian state that consisted essentially of three social classes, the elite, workers and slaves. The elite included advisers, military leaders, courtiers, priests, religious ascetics and officials. Workers included agricultural labourers and also a variety of craftsman for construction projects. Slaves were often captives from military campaigns or distant villages. Coinage did not exist and the barter economy was based on agricultural produce, principally rice, with regional trade as an insignificant part of the economy.[86][87]

Post-Angkor Period of Cambodia (1431–1863)

.svg.png.webp)

The term "Post-Angkor Period of Cambodia", also the "Middle Period"[88] refers to the historical era from the early 15th century to 1863, the beginning of the French Protectorate of Cambodia. Reliable sources – particularly for the 15th and 16th century – are very rare. A conclusive explanation that relates to concrete events manifesting the decline of the Khmer Empire has not yet been produced.[89][90] However, most modern historians contest that several distinct and gradual changes of religious, dynastic, administrative and military nature, environmental problems and ecological imbalance[91] coincided with shifts of power in Indochina and must all be taken into account to make an interpretation.[92][93][94] In recent years, focus has notably shifted towards studies on climate changes, human–environment interactions and the ecological consequences.[95][96][97][98]

Epigraphy in temples, ends in the third decade of the fourteenth, and does not resume until the mid-16th century. Recording of the Royal Chronology discontinues with King Jayavarman IX Parameshwara (or Jayavarma-Paramesvara) – there exists not a single contemporary record of even a king's name for over 200 years. Construction of monumental temple architecture had come to a standstill after Jayavarman VII's reign. According to author Michael Vickery there only exist external sources for Cambodia's 15th century, the Chinese Ming Shilu annals and the earliest Royal Chronicle of Ayutthaya.[99][100] Wang Shi-zhen (王世貞), a Chinese scholar of the 16th century, remarked: "The official historians are unrestrained and are skilful at concealing the truth; but the memorials and statutes they record and the documents they copy cannot be discarded."[101][102]

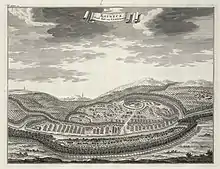

The central reference point for the entire 15th century is a Siamese intervention of some undisclosed nature at the capital Yasodharapura (Angkor Thom) around the year 1431. Historians relate the event to the shift of Cambodia's political centre southward to the region of Phnom Penh, Longvek and later Oudong.[12][11]

"As Siam became Cambodia’s primary nemesis after the demise of Angkor, it put an end to the pattern of ambivalent sovereignty that Cambodia’s imperial experiment on its western frontier had so effectively prolonged."[82]

Sources for the 16th century are more numerous. The kingdom is centred at the Mekong, prospering as an integral part of the Asian maritime trade network,[103][104] via which the first contact with European explorers and adventurers does occur.[105] Wars with the Siamese result in loss of territory and eventually the conquest of the capital Longvek in 1594. Richard Cocks, of the East India Company established trade with Cochin, China, and Cambodia by 1618, but the Cambodia commerce was not authorized by the directors in London and was short-lived until it was revived in 1651, again without authorization.[106] The Vietnamese on their "Southward March" reach Prei Nokor/Saigon at the Mekong Delta in the 17th century. This event initiates the slow process of Cambodia losing access to the seas and independent marine trade.[107]

Siamese and Vietnamese dominance intensified during the 17th and 18th century, resulting in frequent displacements of the seat of power as the Khmer royal authority decreased to the state of a vassal.[108][109] In the early 19th century with dynasties in Vietnam and Siam firmly established, Cambodia was placed under joint suzerainty, having lost its national sovereignty. British agent John Crawfurd states: "...the King of that ancient Kingdom is ready to throw himself under the protection of any European nation..." To save Cambodia from being incorporated into Vietnam and Siam, the Cambodians entreated the aid of the Luzones/Lucoes (Filipinos from Luzon-Philippines) that previously participated in the Burmese-Siamese wars as mercenaries. When the embassy arrived in Luzon, the rulers were now Spaniards, so they asked them for aid too, together with their Latin American troops imported from Mexico, in order to restore the then Christianised King, Satha II, as monarch of Cambodia, this, after a Thai/Siamese invasion was repelled. However that was only temporary. Nevertheless, the future King, Ang Duong, also enlisted the aid of the French who were allied to the Spanish (As Spain was ruled by a French royal dynasty the Bourbons). The Cambodian king agreed to colonial France's offers of protection in order to restore the existence of the Cambodian monarchy, which took effect with King Norodom Prohmbarirak signing and officially recognising the French protectorate on 11 August 1863.[110][111]

French colonial period (1863–1953)

In August 1863 King Norodom signed an agreement with the French placing the kingdom under the protection of France.[40] The original treaty left Cambodian sovereignty intact, but French control gradually increased, with important landmarks in 1877, 1884, and 1897, until by the end of the century the king's authority no longer existed outside the palace.[112] Norodom died in 1904, and his two successors, Sisowath and Monivong, were content to allow the French to control the country, but in 1940 France was defeated in a brief border war with Thailand and forced to surrender the provinces of Battambang and Angkor (the ancient site of Angkor itself was retained). King Monivong died in April 1941,[40] and the French placed the obscure Prince Sihanouk on the throne as king, believing that the inexperienced 18-year old would be more pliable than Monivong's middle-aged son, Prince Monireth.

Cambodia's situation at the end of the war was chaotic.[40] The Free French, under General Charles de Gaulle, were determined to recover Indochina, though they offered Cambodia and the other Indochinese protectorates a carefully circumscribed measure of self-government.[40] Convinced that they had a "civilizing mission", they envisioned Indochina's participation in a French Union of former colonies that shared the common experience of French culture.[113][40]

Administration of Sihanouk (1953–70)

On 9 March 1945, during the Japanese occupation of Cambodia, young king Norodom Sihanouk proclaimed an independent Kingdom of Kampuchea, following a formal request by the Japanese. Shortly thereafter the Japanese government nominally ratified the independence of Cambodia and established a consulate in Phnom Penh.[114] The new government did away with the romanization of the Khmer language that the French colonial administration was beginning to enforce and officially reinstated the Khmer script. This measure taken by the short-lived governmental authority would be popular and long-lasting, for since then no government in Cambodia has tried to romanise the Khmer language again.[115] After Allied military units entered Cambodia, the Japanese military forces present in the country were disarmed and repatriated. The French were able to reimpose the colonial administration in Phnom Penh in October the same year.[116]

Sihanouk's "royal crusade for independence" resulted in grudging French acquiescence to his demands for a transfer of sovereignty. A partial agreement was struck in October 1953. Sihanouk then declared that independence had been achieved and returned in triumph to Phnom Penh. As a result of the 1954 Geneva Conference on Indochina, Cambodia was able to bring about the withdrawal of the Viet Minh troops from its territory and to withstand any residual impingement upon its sovereignty by external powers.

Neutrality was the central element of Cambodian foreign policy during the 1950s and 1960s. By the mid-1960s, parts of Cambodia's eastern provinces were serving as bases for North Vietnamese Army and National Liberation Front (NVA/NLF) forces operating against South Vietnam, and the port of Sihanoukville was being used to supply them. As NVA/VC activity grew, the United States and South Vietnam became concerned, and in 1969, the United States began a 14-month-long series of bombing raids targeted at NVA/VC elements, contributing to destabilisation. The bombing campaign took place no further than ten, and later twenty miles (32 km) inside the Cambodian border, areas where the Cambodian population had been evicted by the NVA.[117] Prince Sihanouk, fearing that the conflict between communist North Vietnam and South Vietnam might spill over to Cambodia, publicly opposed the idea of a bombing campaign by the United States along the Vietnam–Cambodia border and inside Cambodian territory. However, Peter Rodman claimed, "Prince Sihanouk complained bitterly to us about these North Vietnamese bases in his country and invited us to attack them". In December 1967 Washington Post journalist Stanley Karnow was told by Sihanouk that if the US wanted to bomb the Vietnamese communist sanctuaries, he would not object, unless Cambodians were killed.[118] The same message was conveyed to US President Johnson's emissary Chester Bowles in January 1968.[119] So the US had no real motivation to overthrow Sihanouk. However, Prince Sihanouk wanted Cambodia to stay out of the North Vietnam–South Vietnam conflict and was very critical of the United States government and its allies (the South Vietnamese government). Prince Sihanouk, facing internal struggles of his own, due to the rise of the Khmer Rouge, did not want Cambodia to be involved in the conflict. Sihanouk wanted the United States and its allies (South Vietnam) to keep the war away from the Cambodian border. Sihanouk did not allow the United States to use Cambodian air space and airports for military purposes. This upset the United States greatly and contributed to their view of Prince Sihanouk as a North Vietnamese sympathiser and a thorn on the United States.[120] However, declassified documents indicate that, as late as March 1970, the Nixon administration was hoping to garner "friendly relations" with Sihanouk.

Throughout the 1960s, domestic Cambodian politics became polarised. Opposition to the government grew within the middle class and leftists including Paris-educated leaders like Son Sen, Ieng Sary, and Saloth Sar (later known as Pol Pot), who led an insurgency under the clandestine Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). Sihanouk called these insurgents the Khmer Rouge, literally the "Red Khmer". But the 1966 national assembly elections showed a significant swing to the right, and General Lon Nol formed a new government, which lasted until 1967. During 1968 and 1969, the insurgency worsened. However, members of the government and army, who resented Sihanouk's ruling style as well as his tilt away from the United States, did have a motivation to overthrow him.

Khmer Republic and the War (1970–75)

While visiting Beijing in 1970 Sihanouk was ousted by a military coup led by Prime Minister General Lon Nol and Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak in the early hours of 18 March 1970.[121][122] However, as early as 12 March 1970, the CIA Station Chief told Washington that based on communications from Sirik Matak, Lon Nol's cousin, that "the (Cambodian) army was ready for a coup".[123] Lon Nol assumed power after the military coup and immediately allied Cambodia with the United States. Son Ngoc Thanh, an opponent of Pol Pot, announced his support for the new government. On 9 October, the Cambodian monarchy was abolished, and the country was renamed the Khmer Republic. The new regime immediately demanded that the Vietnamese communists leave Cambodia.

Hanoi rejected the new republic's request for the withdrawal of NVA troops. In response, the United States moved to provide material assistance to the new government's armed forces, which were engaged against both CPK insurgents and NVA forces. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, desperate to retain their sanctuaries and supply lines from North Vietnam, immediately launched armed attacks on the new government. The North Vietnamese quickly overran large parts of eastern Cambodia, reaching to within 15 miles (24 km) of Phnom Penh. The North Vietnamese turned the newly won territories over to the Khmer Rouge. The king urged his followers to help in overthrowing this government, hastening the onset of civil war.[124]

In April 1970, US President Richard Nixon announced to the American public that US and South Vietnamese ground forces had entered Cambodia in a campaign aimed at destroying NVA base areas in Cambodia (see Cambodian Incursion).[125] The US had already been bombing Vietnamese positions in Cambodia for well over a year by that point. Although a considerable quantity of equipment was seized or destroyed by US and South Vietnamese forces, containment of North Vietnamese forces proved elusive.

The Khmer Republic's leadership was plagued by disunity among its three principal figures: Lon Nol, Sihanouk's cousin Sirik Matak, and National Assembly leader In Tam. Lon Nol remained in power in part because none of the others were prepared to take his place. In 1972, a constitution was adopted, a parliament elected, and Lon Nol became president. But disunity, the problems of transforming a 30,000-man army into a national combat force of more than 200,000 men, and spreading corruption weakened the civilian administration and army.

The Khmer Rouge insurgency inside Cambodia continued to grow, aided by supplies and military support from North Vietnam. Pol Pot and Ieng Sary asserted their dominance over the Vietnamese-trained communists, many of whom were purged. At the same time, the Khmer Rouge (CPK) forces became stronger and more independent of their Vietnamese patrons. By 1973, the CPK were fighting battles against government forces with little or no North Vietnamese troop support, and they controlled nearly 60% of Cambodia's territory and 25% of its population.

The government made three unsuccessful attempts to enter into negotiations with the insurgents, but by 1974, the CPK was operating openly as divisions, and some of the NVA combat forces had moved into South Vietnam. Lon Nol's control was reduced to small enclaves around the cities and main transportation routes. More than two million refugees from the war lived in Phnom Penh and other cities.

On New Year's Day 1975, Communist troops launched an offensive which, in 117 days of the hardest fighting of the war, caused the collapse of the Khmer Republic. Simultaneous attacks around the perimeter of Phnom Penh pinned down Republican forces, while other CPK units overran fire bases controlling the vital lower Mekong resupply route. A US-funded airlift of ammunition and rice ended when Congress refused additional aid for Cambodia. The Lon Nol government in Phnom Penh surrendered on 17 April 1975, just five days after the US mission evacuated Cambodia.[126]

Foreign involvement in the rise of the Khmer Rouge

The relationship between the massive carpet bombing of Cambodia by the United States and the growth of the Khmer Rouge, in terms of recruitment and popular support, has been a matter of interest to historians. Some historians, including Michael Ignatieff, Adam Jones[127] and Greg Grandin,[128] have cited the United States intervention and bombing campaign (spanning 1965–1973) as a significant factor which lead to increased support for the Khmer Rouge among the Cambodian peasantry.[129] According to Ben Kiernan, the Khmer Rouge "would not have won power without U.S. economic and military destabilization of Cambodia. ... It used the bombing's devastation and massacre of civilians as recruitment propaganda and as an excuse for its brutal, radical policies and its purge of moderate communists and Sihanoukists."[130] Pol Pot biographer David P. Chandler writes that the bombing "had the effect the Americans wanted – it broke the Communist encirclement of Phnom Penh", but it also accelerated the collapse of rural society and increased social polarization.[131][132][133] Peter Rodman and Michael Lind claimed that the United States intervention saved the Lon Nol regime from collapse in 1970 and 1973.[134][135] Craig Etcheson acknowledged that U.S. intervention increased recruitment for the Khmer Rouge but disputed that it was a primary cause of the Khmer Rouge victory.[136] William Shawcross wrote that the United States bombing and ground incursion plunged Cambodia into the chaos that Sihanouk had worked for years to avoid.[137]

By 1973, Vietnamese support of the Khmer Rouge had largely disappeared.[138] China "armed and trained" the Khmer Rouge both during the civil war and the years afterward.[139]

Owing to Chinese, U.S., and Western support, the Khmer Rouge-dominated Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) held Cambodia's UN seat until 1993, long after the Cold War had ended.[140] China has defended its ties with the Khmer Rouge. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu said that "the government of Democratic Kampuchea had a legal seat at the United Nations, and had established broad foreign relations with more than 70 countries".[141]

Democratic Kampuchea (Khmer Rouge era) (1975–79)

Immediately after its victory, the CPK ordered the evacuation of all cities and towns, sending the entire urban population into the countryside to work as farmers, as the CPK was trying to reshape society into a model that Pol Pot had conceived.

The new government sought to completely restructure Cambodian society. Remnants of the old society were abolished and religion was suppressed.[142][143] Agriculture was collectivised, and the surviving part of the industrial base was abandoned or placed under state control. Cambodia had neither a currency nor a banking system.

Democratic Kampuchea's relations with Vietnam and Thailand worsened rapidly as a result of border clashes and ideological differences. While communist, the CPK was fiercely nationalistic, and most of its members who had lived in Vietnam were purged. Democratic Kampuchea established close ties with the People's Republic of China, and the Cambodian-Vietnamese conflict became part of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, with Moscow backing Vietnam. Border clashes worsened when the Democratic Kampuchea military attacked villages in Vietnam. The regime broke off relations with Hanoi in December 1977, protesting Vietnam's alleged attempt to create an Indochina Federation. In mid-1978, Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia, advancing about 30 miles (48 km) before the arrival of the rainy season.

The reasons for Chinese support of the CPK was to prevent a pan-Indochina movement, and maintain Chinese military superiority in the region. The Soviet Union supported a strong Vietnam to maintain a second front against China in case of hostilities and to prevent further Chinese expansion. Since Stalin's death, relations between Mao-controlled China and the Soviet Union had been lukewarm at best. In February to March 1979, China and Vietnam would fight the brief Sino-Vietnamese War over the issue.

In December 1978, Vietnam announced the formation of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (KUFNS)[40] under Heng Samrin, a former DK division commander. It was composed of Khmer Communists who had remained in Vietnam after 1975 and officials from the eastern sector—like Heng Samrin and Hun Sen—who had fled to Vietnam from Cambodia in 1978. In late December 1978, Vietnamese forces launched a full invasion of Cambodia, capturing Phnom Penh on 7 January 1979 and driving the remnants of Democratic Kampuchea's army westward toward Thailand.

Within the CPK, the Paris-educated leadership—Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Nuon Chea, and Son Sen—were in control. A new constitution in January 1976 established Democratic Kampuchea as a Communist People's Republic, and a 250-member Assembly of the Representatives of the People of Kampuchea (PRA) was selected in March to choose the collective leadership of a State Presidium, the chairman of which became the head of state.

Prince Sihanouk resigned as head of state on 2 April.[40] On 14 April, after its first session, the PRA announced that Khieu Samphan would chair the State Presidium for a 5-year term. It also picked a 15-member cabinet headed by Pol Pot as prime minister. Prince Sihanouk was put under virtual house arrest.

Destruction and deaths caused by the regime

.jpg.webp)

20,000 people died of exhaustion or disease during the evacuation of Phnom Penh and its aftermath. Many of those forced to evacuate the cities were resettled in newly created villages, which lacked food, agricultural implements, and medical care. Many who lived in cities had lost the skills necessary for survival in an agrarian environment. Thousands starved before the first harvest. Hunger and malnutrition—bordering on starvation—were constant during those years. Most military and civilian leaders of the former regime who failed to disguise their pasts were executed.

Some of the ethnicities in Cambodia, such as the Cham and Vietnamese, suffered specific and targeted and violent persecutions, to the point of some international sources referring to it as the "Cham genocide". Entire families and towns were targeted and attacked with the goal of significantly diminishing their numbers and eventually eliminated them. Life in 'Democratic Kampuchea' was strict and brutal. In many areas of the country people were rounded up and executed for speaking a foreign language, wearing glasses, scavenging for food, absent for government assigned work, and even crying for dead loved ones. Former businessmen and bureaucrats were hunted down and killed along with their entire families; the Khmer Rouge feared that they held beliefs that could lead them to oppose their regime. A few Khmer Rouge loyalists were even killed for failing to find enough 'counter-revolutionaries' to execute.

When Cambodian socialists began to rebel in the eastern zone of Cambodia, Pol Pot ordered his armies to exterminate 1.5 million eastern Cambodians which he branded as "Cambodians with Vietnamese minds" in the area.[144] The purge was done speedily and efficiently as Pol Pot's soldiers quickly killed at least more than 100,000 to 250,000 eastern Cambodians right after deporting them to execution site locations in Central, North and North-Western Zones within a month's time,[145] making it the bloodiest episode of mass murder under Pol Pot's regime.

Religious institutions were not spared by the Khmer Rouge as well, in fact religion was so viciously persecuted to such an extent that the vast majority of Cambodia's historic architecture, 95% of Cambodia's Buddhist temples, was completely destroyed.[146]

Ben Kiernan estimates that 1.671 million to 1.871 million Cambodians died as a result of Khmer Rouge policy, or between 21% and 24% of Cambodia's 1975 population.[147] A study by French demographer Marek Sliwinski calculated slightly fewer than 2 million unnatural deaths under the Khmer Rouge out of a 1975 Cambodian population of 7.8 million; 33.5% of Cambodian men died under the Khmer Rouge compared to 15.7% of Cambodian women.[148] According to a 2001 academic source, the most widely accepted estimates of excess deaths under the Khmer Rouge range from 1.5 million to 2 million, although figures as low as 1 million and as high as 3 million have been cited; conventionally accepted estimates of deaths due to Khmer Rouge executions range from 500,000 to 1 million, "a third to one half of excess mortality during the period."[149] However, a 2013 academic source (citing research from 2009) indicates that execution may have accounted for as much as 60% of the total, with 23,745 mass graves containing approximately 1.3 million suspected victims of execution.[150] While considerably higher than earlier and more widely accepted estimates of Khmer Rouge executions, the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)'s Craig Etcheson defended such estimates of over one million executions as "plausible, given the nature of the mass grave and DC-Cam's methods, which are more likely to produce an under-count of bodies rather than an over-estimate."[140] Demographer Patrick Heuveline estimated that between 1.17 million and 3.42 million Cambodians died unnatural deaths between 1970 and 1979, with between 150,000 and 300,000 of those deaths occurring during the civil war. Heuveline's central estimate is 2.52 million excess deaths, of which 1.4 million were the direct result of violence.[149][140] Despite being based on a house-to-house survey of Cambodians, the estimate of 3.3 million deaths promulgated by the Khmer Rouge's successor regime, the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK), is generally considered to be an exaggeration; among other methodological errors, the PRK authorities added the estimated number of victims that had been found in the partially-exhumed mass graves to the raw survey results, meaning that some victims would have been double-counted.[140]

An estimated 300,000 Cambodians starved to death between 1979 and 1980, largely as a result of the after-effects of Khmer Rouge policies.[151]

Vietnamese occupation and the PRK (1979–93)

On 10 January 1979, after the Vietnamese army and the KUFNS (Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation) invaded Cambodia and overthrew the Khmer Rouge, the new People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) was established with Heng Samrin as head of state. Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge forces retreated rapidly to the jungles near the Thai border. The Khmer Rouge and the PRK began a costly struggle that played into the hands of the larger powers China, the United States and the Soviet Union. The Khmer People's Revolutionary Party's rule gave rise to a guerrilla movement of three major resistance groups – the FUNCINPEC (Front Uni National pour un Cambodge Indépendant, Neutre, Pacifique, et Coopératif), the KPLNF (Khmer People's National Liberation Front) and the PDK (Party of Democratic Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge under the nominal presidency of Khieu Samphan).[152] "All held dissenting perceptions concerning the purposes and modalities of Cambodia's future". Civil war displaced 600,000 Cambodians, who fled to refugee camps along the border to Thailand and tens of thousands of people were murdered throughout the country.[153][154][155]

Peace efforts began in Paris in 1989 under the State of Cambodia, culminating two years later in October 1991 in a comprehensive peace settlement. The United Nations was given a mandate to enforce a ceasefire and deal with refugees and disarmament known as the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC).[156]

Modern Cambodia (1993–present)

.jpg.webp)

On 23 October 1991, the Paris Conference reconvened to sign a comprehensive settlement giving the UN full authority to supervise a cease-fire, repatriate the displaced Khmer along the border with Thailand, disarm and demobilise the factional armies, and prepare the country for free and fair elections. Prince Sihanouk, President of the Supreme National Council of Cambodia (SNC), and other members of the SNC returned to Phnom Penh in November 1991, to begin the resettlement process in Cambodia.[157] The UN Advance Mission for Cambodia (UNAMIC) was deployed at the same time to maintain liaison among the factions and begin demining operations to expedite the repatriation of approximately 370,000 Cambodians from Thailand.[158][159]

On 16 March 1992, the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) arrived in Cambodia to begin implementation of the UN settlement plan and to become operational on 15 March 1992 under Yasushi Akashi, the Special Representative of the U.N. Secretary General.[160][161] UNTAC grew into a 22,000-strong civilian and military peacekeeping force tasked to ensure the conduct of free and fair elections for a constituent assembly.[162]

Over 4 million Cambodians (about 90% of eligible voters) participated in the May 1993 elections. Pre-election violence and intimidation was widespread, caused by SOC (State of Cambodia – made up largely of former PDK cadre) security forces, mostly against the FUNCINPEC and BLDP parties according to UNTAC.[163][164] The Khmer Rouge or Party of Democratic Kampuchea (PDK), whose forces were never actually disarmed or demobilized blocked local access to polling places.[165] Prince Ranariddh's (son of Norodom Sihanouk) royalist Funcinpec Party was the top vote recipient with 45.5% of the vote, followed by Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party and the Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party, respectively. Funcinpec then entered into a coalition with the other parties that had participated in the election. A coalition government resulted between the Cambodian People's Party and FUNCINPEC, with two co-prime ministers – Hun Sen, since 1985 the prime minister in the Communist government, and Norodom Ranariddh.[166]

The parties represented in the 120-member assembly proceeded to draft and approve a new constitution, which was promulgated 24 September 1993. It established a multiparty liberal democracy in the framework of a constitutional monarchy, with the former Prince Sihanouk elevated to King. Prince Ranariddh and Hun Sen became First and Second Prime Ministers, respectively, in the Royal Cambodian Government (RGC). The constitution provides for a wide range of internationally recognised human rights.[167]

Hun Sen and his government have seen much controversy. Hun Sen was a former Khmer Rouge commander who was originally installed by the Vietnamese and, after the Vietnamese left the country, maintains his strong man position by violence and oppression when deemed necessary.[168] In 1997, fearing the growing power of his co-Prime Minister, Prince Norodom Ranariddh, Hun launched a coup, using the army to purge Ranariddh and his supporters. Ranariddh was ousted and fled to Paris while other opponents of Hun Sen were arrested, tortured and some summarily executed.[168][169]

On 4 October 2004, the Cambodian National Assembly ratified an agreement with the United Nations on the establishment of a tribunal to try senior leaders responsible for the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge.[170] International donor countries have pledged a US$43 Million share of the three-year tribunal budget as Cambodia contributes US$13.3 Million. The tribunal has sentenced several senior Khmer Rouge leaders since 2008.[171]

Cambodia is still infested with countless land mines, indiscriminately planted by all warring parties during the decades of war and upheaval.[172]

The Cambodia National Rescue Party was dissolved ahead of the 2018 Cambodian general election and the ruling Cambodian People's Party also enacted tighter curbs on mass media.[173] The CPP won every seat in the National Assembly without a major opposition, effectively solidifying de facto one-party rule in the country.[174][175]

Cambodia’s longtime Prime Minister Hun Sen, one of the world’s longest-serving leaders, has a very firm grip on power. He has been accused of the crackdown on opponents and critics. His Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has been in power since 1979. In December 2021, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced his support for his son Hun Manet to succeed him after the next election, which is expected to take place in 2023.[176]

In July 2023 election, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) easily won by landslide in flawed election, after disqualification of Cambodia’s most important opposition, Candlelight Party.[177] On 22 August 2023, Hun Manet was sworn in as the new Cambodian prime minister.[178]

See also

References

- Chandler, David (July 2009). "Cambodian History: Searching for the Truth". Cambodia Tribunal Monitor. Northwestern Primary School of Law Center for International Human Rights and Documentation Center of Cambodia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

We have evidence of cave dwellers in northwestern Cambodia living as long ago as 5000 BCE.

- Mourer, Cécile; Mourer, Roland (July 1970). "The Prehistoric Industry of Laang Spean, Province of Battambang, Cambodia". Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceania. Oceania Publications, University of Sydney. 5 (2): 128–146. JSTOR 40386114.

- Stark, Miriam T. (2006). "Pre-Angkorian Settlement Trends in Cambodia's Mekong Delta and the Lower Mekong Archaeological Project" (PDF). Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 26: 98–109. doi:10.7152/bippa.v26i0.11998. hdl:10524/1535. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

The Mekong delta played a central role in the development of Cambodia's earliest complex polities from approximately 500 BCE to 600 CE... envoys Kang Dai and Zhu Ying visited the delta in the mid-3rd century CE to explore the nature of the sea passage via Southeast Asia to India 🇮🇳.. a tribute-based economy, that ... It also suggests that the region's importance continued unabated

- Stark, Miriam T.; Griffin, P. Bion; Phoeurn, Chuch; Ledgerwood, Judy; et al. (1999). "Results of the 1995–1996 Archaeological Field Investigations at Angkor Borei, Cambodia" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. University of Hawai'i-Manoa. 38 (1): 7–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

the development of maritime commerce and Hindu influence stimulated early state formation in polities along the coasts of mainland Southeast Asia, where passive indigenous populations embraced notions of statecraft and ideology introduced by outsiders...

- ""What and Where was Chenla?", Recherches nouvelles sur le Cambodge" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "Considerations on the Chronology and History of 9th Century Cambodia by Dr. Karl-Heinz Golzio, Epigraphist - ...the realm called Zhenla by the Chinese. Their contents are not uniform but they do not contradict each other" (PDF). Khmer Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Wolters, O. W. (1973). "Jayavarman II's Military Power: The Territorial Foundation of the Angkor Empire". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 105 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00130400. JSTOR 25203407. S2CID 161969465.

- "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire - Many scholars attribute the halt of the development of Angkor to the rise of Theravada...p.14" (PDF). Studies Of ASEAN Countries in the Southeast Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "Khmer Empire". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "AN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY INSCRIPTION FROM ANGKOR WAT by David P. Chandler" (PDF). The Siam Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Kingdom of Cambodia – 1431–1863". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Ross Marlay; Clark D. Neher (1999). Patriots and Tyrants: Ten Asian Leaders. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8476-8442-7.

- "Murder and Mayhem in Seventeenth Century Cambodia". Institute of Historical Research (IHR). Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Maritime Trade in Southeast Asia during the Early Colonial Period ...transferring the lucrative China trade to Cambodia..." (PDF). Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- "1551 – WAR WITH LOVEK – During the Burmese siege of Ayutthaya in 1549 the King of Cambodia, Ang Chan..." History of Ayutthaya. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Nicholas Tarling (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-66370-0.

- "Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese History from the 15th to 18th Centuries Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambodia by Brian A. Zottoli". University of Michigan. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Smithies, Michael (8 March 2010). "The great Lao buffer zone". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- LePoer, Barbara Leitch, ed. (1987). "The Crisis of 1893". Thailand: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Cambodia became a peripheral area, widely uncared for by France as economic benefits from Cambodia were negligible" (PDF). Max-Planck-Institut. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "CAMBODIA'S BORDER WITH ENGAGEMENT FROM POWER COUNTRIES by SORIN SOK, Research Fellow – The treaty of 1863" (PDF). Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Marie Alexandrine Martin (1994). Cambodia: A Shattered Society. University of California Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-520-07052-3.

- "COMMUNISM AND CAMBODIA – Cambodia first declared independence from the French while occupied by the Japanese. Sihanouk, then King, made the declaration on 12 March 1945, three days after Hirohito's Imperial Army seized and disarmed wavering French garrisons throughout Indo-China" (PDF). DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Simulation on The Cambodia Peace Settlement – The Sihanouk Era – The government of the new kingdom initially took a neutral stance in order to protect itself from neighboring countries". UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Conflict in Cambodia, 1945–2002 by Ben Kiernan – American aircraft dropped over half a million tons of bombs on Cambodia's countryside, killing over 100.000 peasants..." (PDF). Yale University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Cambodia – History". Sandbox Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Joachim Schliesinger (2015). Ethnic Groups of Cambodia Vol 1: Introduction and Overview. Booksmango. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-63323-232-7.

- David Chandler, A History of Cambodia (Westview Publishers: Boulder Colorado, 2008) p. 13.

- Forestier, Hubert; Sophady, Heng; Puaud, Simon; Celiberti, Vincenzo; Frère, Stéphane; Zeitoun, Valéry; Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile; Mourer, Roland; Than, Heng; Billault, Laurence (2015). "The Hoabinhian from Laang Spean Cave in its stratigraphic, chronological, typo-technological and environmental context (Cambodia, Battambang province)". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 3: 194–206. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.06.008.

- "Human origin sites and the World Heritage Convention in Asia – The case of Phnom Teak Treang and Laang Spean cave, Cambodia: The potential for World Heritage site nomination; the significance of the site for human evolution in Asia, and the need for international cooperation" (PDF). World Heritage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000), "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan", Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 20: 153–158, doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751

- Turton, M. (2021). Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south. Taiwan's relations with the Philippines date back millennia, so it's a mystery that it's not the jewel in the crown of the New Southbound Policy. Taiwan Times.

- Everington, K. (2017). Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar. Taiwan News.

- Bellwood, P., H. Hung, H., Lizuka, Y. (2011). Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction. Semantic Scholar.

- "Circular Earthwork Krek 52/62: Recent Research on the Prehistory of Cambodia" (PDF). Project MUSE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Domett, K. M. (2 January 2015). "Bioarchaeological evidence for conflict in Iron Age north-west Cambodia - Examination of skeletal material from graves at Phum Snay in north-west Cambodia revealed an exceptionally high number of injuries..." Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. 85 (328): 441–458. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067867. S2CID 162907346.

- "Art and Archaeology of Fu-Nan" (PDF). Department of Anthropology College of Social Sciences University of Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "Trade and Exchange Networks in Iron Age Cambodia: Preliminary Results from a Compositional Analysis of Glass Beads - Beads made of glass and stone found at Iron Age period sites (500 BCE – 500 CE) in Southeast Asia are amongst the first signs for sustained trade and sociopolitical contact with South Asia..." Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. doi:10.7152/bippa.v30i0.9966. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) -

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Ross, Russell R., ed. (1990). Cambodia: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 4, 6, 20, 22, 59, 69. OCLC 44355152.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Ross, Russell R., ed. (1990). Cambodia: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 4, 6, 20, 22, 59, 69. OCLC 44355152. - "THE VIRTUAL MUSEUM OF KHMER ART - History of Funan - The Liang Shu account from Chinese Empirical Records". Wintermeier collection. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Stark, Miriam T. (2003). "Chapter III: Angkor Borei and the Archaeology of Cambodia's Mekong Delta" (PDF). In Khoo, James C. M. (ed.). Art and Archaeology of Fu Nan. Bangkok: Orchid Press. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

Archaeolgic, epigraphic and art historical research illustrate, that the delta was the center of the region's first cultural system with trappings of statehood...

- "Southeast Asian Riverine and Island Empires by Candice Goucher, Charles LeGuin, and Linda Walton - Funan rulers of the early first century legitimized their rule on the basis of claimed descent from heroic ancestors" (PDF). The Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Pre-Angkorian and Angkorian Cambodia by Miriam T. Stark - Chinese documentary evidence described walled and moated cities..." (PDF). Khamkoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Southeast Asian Riverine and Island Empires by Candice Goucher, Charles LeGuin, and Linda Walton - Early Funan was composed of a number of communities..." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Khmer Ceramics by Dawn Rooney – The language of Funan was..." (PDF). Oxford University Press 1984. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–127, 196–197. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- "Funan Kingdom - 100-545 CE - In the mid-3rd century A.D. two chinese traders, Kang Tai and Zhu Ying, visited Vyadharapura". Global Security. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations by Charles F. W. Higham – the inscriptions, written in Sanskrit and employing the Indian Brahmi script, record the presence of kings and queens who took Indian names and founded temples dedicated to Indian gods" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Khmer Ceramics by Dawn Rooney – Funan became an important centre because it controlled strategic land routes in addition to coastal areas" (PDF). Oxford University Press 1984. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Pre-Angkorian and Angkorian Cambodia by Miriam T. Stark – ...economic and administrative hub" (PDF). Khamkoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "The "Indianization" of Funan: An Economic History of Southeast Asia's First State by Kenneth R. Hall – providing suitable stopping places for sailors and traders; available to them were food, water, and shelter as well as storage facilities and market places for exchange..." Kenneth R. Hall. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Funan Kingdom – 100–545 CE The remains of what is believed to have been the kingdom's main port, Oc Eo (now part of Vietnam), contain Roman as well as Persian, Indian, and Greek artefacts". Global Security. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "9 Textualized Places, Pre-Angkorian Khmers and Historicized Archaeology by Miriam T. Stark – Cambodia's Origins and the Khok Thlok Story" (PDF). University of Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Funan Reviewed : Deconstructing the Ancients In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 90–91, 2003. pp. 101–143. – In that case the place from which the stranger started his voyage to Funan would have been on the east coast of the Malay peninsula" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Kalinga and Funan : A Study in Ancient Relations – there is considerable disagreement on the homeland of Kaundinya" (PDF). Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Funan Reviewed : Deconstructing the Ancients In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 90–91, 2003. pp. 101–143. – Altogether there are 4 versions differing among themselves in interesting ways. – The first version..." (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Kalinga and Funan: A Study in Ancient Relations – This Chinese version of the dynastic origin of Funan has been corroborated by a Sanskrit inscription of Champa belonging to the third century CE" (PDF). Government of Odisha. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Southeast Asian Riverine and Island Empires by Candice Goucher, Charles LeGuin, and Linda Walton – The mythical account of the founding of Funan reflects in symbolic terms the conditions..." (PDF). The Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Funan Reviewed : Deconstructing the Ancients In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 90–91, 2003. pp. 101–143. – there is no evidence that the initial foreign conqueror came from India, neither is it clear that he was a Brahman, and almost certainly his name, as given to the Chinese, was not Kaundinya..." (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Thinking Through Srivijaya: Polycentric Networks in Traditional Southeast Asia By Rosita Dellios and R. James Ferguson – Yet Funan, like Srivijaya, was not a straightforward country/state or "guo" in the Western or Chinese sense. Funan has been shown to be "a conglomerate of chiefdoms but not a state"" (PDF). Bond University Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Funan Reviewed : Deconstructing the Ancients In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 90–91, 2003. pp. 101–143. – What was Funan? Nevertheless, it is a priori unlikely that..." (PDF). Michael Vickery. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "A Short History of South East Asia Chapter 1. Early Movements of PeopIes, Indian Influence – The First States on the Mainland Cambodia (Funan) – Vassal kingdoms spread to southern Vietnam in the east and to the Malay peninsula in the west" (PDF). Stanford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Southeast Asian Riverine and Island Empires by Candice Goucher, Charles LeGuin, and Linda Walton – Here we will look at two empires" (PDF). The Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: FUNAN, SRIVIJAYA AND THE MON". Facts and Details. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ""What and Where was Chenla?" George Coedes". Michael Vickery.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Southeast Asian Riverine and Island Empires by Candice Goucher, Charles LeGuin, and Linda Walton - By the end of the fifth century, international trade through" (PDF). The Annenberg Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "What and Where was Chenla?". Michael Vickery.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Stark, Miriam T. (1998). "The Transition to History in the Mekong by Miriam T. Stark - There is another untapped role for archaeological approaches to the early historic period...". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 2 (3): 175–203. doi:10.1023/A:1027368225043. S2CID 17588289.

- "Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations by Charles F. W. Higham - Chenla - Chinese histories record that a state called Chenla..." (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ""What and Where was Chenla?" - In the 1970s Claude Jacques began cautiously to move away from the established historiographical framework" (PDF). Michael Vickery. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ""What and Where was Chenla?" - there is really no need to look for Khmer Empire beyond the borders of what is present-day Cambodia. All that is required is that it be inland from Funan" (PDF). Michael Vickery publications. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "THE JOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY - AN HISTORICAL ATLAS OF THAILAND Vol. LII Part 1-2 1964 - The Australian National University Canberra" (PDF). The Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Chenla – 550–800". Global Security. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "The Kingdom of Chenla". Asia's World. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Jacques Dumarçay; Pascal Royère (2001). Cambodian Architecture: Eighth to Thirteenth Centuries. BRILL. p. 109. ISBN 978-90-04-11346-6.

- "THE JOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY - AN HISTORICAL ATLAS OF THAILAND Vol. LII Part 1-2 1964 - The Australian National University Canberra" (PDF). The Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Sengupta, Arputha Rani, ed. (2005). God and King: The Devaraja Cult in South Asian Art & Architecture. ISBN 978-8189233266. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "The water management network of Angkor, Cambodia Roland Fletcher Dan Penny, Damián Evans, Christophe Pottier, Mike Barbetti, Matti Kummu, Terry Lustig & Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap (APSARA) Department of Monuments and Archaeology Team" (PDF). University of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire – Many scholars attribute the halt of the development of Angkor to the rise of Theravada..." (PDF). Studies Of Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Lowman, Ian Nathaniel (2011). The Descendants of Kambu: The Political Imagination of Angkorian Cambodia (PhD dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- "GEOHYDROLOGY AND THE DECLINE OF ANGKOR by HENG L. THUNG" (PDF). Khamkoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Historie routes to Angkor: development of the Khmer road system (ninth to thirteenth centuries CE) in mainland Southeast Asia by Mitch Hendrickson" (PDF). University of Sydney. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "Zhou Daguan-A Record of Cambodia-Siam Society Review by Milton Osborne". The Great Khmer Empire. December 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire was paralleled with development and subsequent change in religious ideology, together with infrastructure that supported agriculture by Kay McCullough" (PDF). National Academy of Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Marr, David G.; Milner, Anthony Crothers (1986). Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. p. 244. ISBN 978-9971-988-39-5.

- "Murder and Mayhem in Seventeenth Century Cambodia – The so-called middle period of Cambodian history, stretching from... – Reviews in History". School of Advanced Study at the University of London. 28 February 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "What the collapse of ancient capitals can teach us about the cities of today by Srinath Perur – There had long been a debate about what led to the decline of Angkor and the southward move of the Khmer..." The Guardian. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "Cambodia and Its Neighbors in the 15th Century, Michael Vickery". Michael Vickery’s Publications. 1 June 2004. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "Scientists dig and fly over Angkor in search of answers to golden city's fall by Miranda Leitsinger". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 13 June 2004. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "What Caused the End of the Khmer Empire By K. Kris Hirst". About com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "THE DECLINE OF ANGKOR". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire was paralleled with development and subsequent change in religious ideology, together with infrastructure that supported agriculture" (PDF). Studies Of Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Laser scans flesh out the saga of Cambodias 1200 year old lost city". KHMER GEO. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Possible new explanation found for sudden demise of Khmer Empire". Phys org. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "The emergence and ultimate decline of the Khmer Empire – ...the Empire experienced two lengthy droughts, during c.1340–1370 and also c.1400–1425..." (PDF). Studies of Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Buckley, B. M.; Anchukaitis, K. J.; Penny, D.; Fletcher, R.; Cook, E. R.; Sano, M.; Nam, L. C.; Wichienkeeo, A.; Minh, T. T.; Hong, T. M. (2010). "Climate as a contributing factor in the demise of Angkor, Cambodia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (15): 6748–6752. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6748B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910827107. PMC 2872380. PMID 20351244.

- "Mak Phœun : Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle" (PDF). Michael Vickery. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "The Ming Shi-lu as a Source for the Study of Southeast Asian History". Southeast Asia in the Ming Shi-lu. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "The Ming Shi-lu as a source for Southeast Asian History by Geoff Wade, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore 2.5 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MSL AS A HISTORICAL SOURCE" (PDF). National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "THE ABRIDGED ROYAL CHRONICLE OF AYUDHYA" (PDF). The Siam Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Giovanni Filippo de MARINI, Delle Missioni… CHAPTER VII – MISSION OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA by Cesare Polenghi – It is considered one of the most renowned for trading opportunities: there is abundance..." (PDF). The Siam Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Anthony Reid (2000). Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Silkworm Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-63041-481-8.

- "Maritime Trade in Southeast Asia during the Early Colonial Period" (PDF). University of Oxford. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Bassett, D. K. “The Trade of the English East India Company in Cambodia, 1651-1656.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 1/2, 1962, pp. 35–61. JSTOR website Retrieved 23 Oct. 2023.

- Peter Church (2012). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-118-35044-7.

- Cathal J. Nolan (2002). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1653. ISBN 978-0-313-32383-6.

- Keat Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. p. 566. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- "London Company's Envoys Plot Siam" (PDF). Siamese Heritage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Owen, Norman G. (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.