Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav I Vladimirovich[lower-alpha 1] (c. 978–20 February 1054), better known as Yaroslav the Wise,[lower-alpha 2] was Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death in 1054. He was also earlier Prince of Novgorod from 1010 to 1034 and Prince of Rostov from 987 to 1010, uniting the principalities for a time. Yaroslav's baptismal name was George[lower-alpha 3] after Saint George.[2]

| Yaroslav the Wise | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

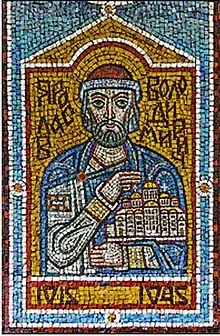

The only contemporary image of Yaroslav I the Wise, on his seal | |||||

| Grand Prince of Kiev | |||||

| Reign | 1019–1054 | ||||

| Predecessor | Sviatopolk the Accursed | ||||

| Successor | Iziaslav I | ||||

| Prince of Novgorod | |||||

| Reign | 1010–1034 | ||||

| Prince of Rostov (?) | |||||

| Reign | 978–1010 | ||||

| Born | c. 978 or c. 988 | ||||

| Died | 28 February 1054 (aged 75 or 76) Vyshhorod, Kievan Rus | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden | ||||

| Issue Details... | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Volodimerovichi | ||||

| Father | Vladimir the Great | ||||

| Mother | Rogneda of Polotsk or Anna Porphyrogenita | ||||

| Insignia |  | ||||

Yaroslav was a son of Vladimir the Great and Rogneda of Polotsk. Yaroslav ruled the northern lands around Rostov before being transferred to Novgorod in 1010. He had a strained relationship with his father and refused to pay tribute to Kiev in 1014. Following Vladimir's death in 1015, Yaroslav waged a complicated war for the Kievan throne against his half-brother Sviatopolk, ultimately emerging victorious in 1019.

As the Grand Prince of Kiev, Yaroslav focused on foreign policy, forming alliances with Scandinavian countries and weakening Byzantine influence on Kiev. He successfully captured the area around present-day Tartu, Estonia, establishing the fort of Yuryev, and forced nearby regions to pay tribute. Yaroslav also defended his state against nomadic tribes such as the Pechenegs by constructing a line of forts. He was a patron of literary culture, sponsoring the construction of Saint Sophia Cathedral in 1037 and promoting the first work of Old East Slavic literature by Hilarion of Kiev.

Yaroslav married Ingegerd Olofsdotter in 1019 and had several children who married into foreign royal families. His children from his second marriage went on to rule various parts of Kievan Rus'. Yaroslav was known for promoting unity among his children and emphasizing the importance of living in peace. After his death, his body was placed in a sarcophagus within Saint Sophia's Cathedral, but his remains were later lost or stolen. Yaroslav's legacy includes founding several towns and having numerous monuments and institutions named after him.

Rise to the throne

.jpg.webp)

The early years of Yaroslav's life are mostly unknown. He was one of the numerous sons of Vladimir the Great, presumably his second by Rogneda of Polotsk,[3] although his actual age (as stated in the Primary Chronicle and corroborated by the examination of his skeleton in the 1930s)[4] would place him among the youngest children of Vladimir.[5]

It has been suggested that he was a child begotten out of wedlock after Vladimir's divorce from Rogneda and marriage to Anna Porphyrogenita, or even that he was a child of Anna Porphyrogenita herself. French historian Jean-Pierre Arrignon argues that he was indeed Anna's son, as this would explain his interference in Byzantine affairs in 1043.[5]

Furthermore, Yaroslav's maternity by Rogneda of Polotsk has been questioned since Mykola Kostomarov in the 19th century.[6][7][8] Yaroslav figures prominently in the Norse sagas under the name Jarisleif the Lame; his legendary lameness (probably resulting from an arrow wound) was corroborated by the scientists who examined his remains.

In his youth, Yaroslav was sent by his father to rule the northern lands around Rostov. He was transferred to Veliky Novgorod,[9] as befitted a senior heir to the throne, in 1010. While living there, he founded the town of Yaroslavl (literally, "Yaroslav's") on the Volga River. His relations with his father were apparently strained,[9] and grew only worse on the news that Vladimir bequeathed the Kievan throne to his younger son, Boris. In 1014 Yaroslav refused to pay tribute to Kiev and only Vladimir's death, in July 1015, prevented a war.[9]

During the next four years Yaroslav waged a complicated and bloody war for Kiev against his half-brother Sviatopolk I of Kiev, who was supported by his father-in-law, Duke Bolesław I the Brave (King of Poland from 1025).[10] During the course of this struggle, several other brothers (Boris, Gleb, and Svyatoslav) were brutally murdered.[10][11] The Primary Chronicle accused Sviatopolk of planning those murders.[10] The saga Eymundar þáttr hrings is often interpreted as recounting the story of Boris' assassination by the Varangians in the service of Yaroslav.

However, the victim's name is given there as Burizaf, which is also a name of Boleslaus I in the Scandinavian sources. It is thus possible that the Saga tells the story of Yaroslav's struggle against Sviatopolk (whose troops were commanded by the Polish duke), and not against Boris.

Yaroslav defeated Sviatopolk in their first battle, in 1016, and Sviatopolk fled to Poland.[10] Sviatopolk returned in 1018 with Polish troops furnished by his father-in-law, seized Kiev,[10] and pushed Yaroslav back into Novgorod. Yaroslav prevailed over Sviatopolk, and in 1019 firmly established his rule over Kiev.[12] One of his first actions as a grand prince was to confer on the loyal Novgorodians, who had helped him to gain the Kievan throne, numerous freedoms and privileges.

Thus, the foundation of the Novgorod Republic was laid. For their part, the Novgorodians respected Yaroslav more than they did other Kievan princes; and the princely residence in their city, next to the marketplace (and where the veche often convened) was named Yaroslav's Court after him. It probably was during this period that Yaroslav promulgated the first code of laws in the lands of the East Slavs, the Russkaya Pravda.

Reign

Power struggles between siblings

Leaving aside the legitimacy of Yaroslav's claims to the Kievan throne and his postulated guilt in the murder of his brothers, Nestor the Chronicler and later Russian historians often presented him as a model of virtue, styling him "the Wise". A less appealing side of his personality is revealed by his having imprisoned his youngest brother Sudislav for life. In response, another brother, Mstislav of Chernigov, whose distant realm bordered the North Caucasus and the Black Sea, hastened to Kiev.

Despite reinforcements led by Yaroslav's brother-in-law King Anund Jacob of Sweden (as Yakun - "blind and dressed in a gold suit"[13] or "handsome and dressed in a gold suit")[14] Mstislav inflicted a heavy defeat on Yaroslav in 1024. Yaroslav and Mstislav then divided Kievan Rus' between them: the area stretched east from the Dnieper River, with the capital at Chernigov, was ceded to Mstislav until his death in 1036.

Allies along the Baltic coast

In his foreign policy, Yaroslav relied on a Scandinavian alliance and attempted to weaken the Byzantine influence on Kiev. According to Heimskringla, Olaf the Swede made an alliance with Yaroslav, even though the alliance was not liked in Sweden, in order to declare war against Olaf II of Norway. This was sealed in 1019 when King Olof of Sweden married his daughter to Yaroslav instead of the Norwegian king. That led to protests in Sweden because the Swedes wanted to reestablish control over their lost eastern territories and bring in tribute from Kievan Rus', as his father Eric the Victorious had, but after years of war against Norway, Sweden no longer had the power to collect regular tributes from Kievan Rus', according to Heimskringla. In 1022 Olaf was deposed and forced to give power to his son Anund Jakob.[15]

He manfully defended the Eastern countries from invaders, ensuring Swedish military interests.[15]

In a successful military raid in 1030, he captured Tartu, Estonia and renamed it Yuryev[16] (named after Yury, Yaroslav's patron saint) and forced the surrounding Ugandi County to pay annual tribute.

In 1031, he conquered Cherven cities from the Poles followed by the construction of Sutiejsk to guard the newly acquired lands. In c.1034 Yaroslav concluded an alliance with Polish King Casimir I the Restorer, sealed by the latter's marriage to Yaroslav's sister, Maria.

Yaroslav's eldest son, Vladimir, ruled in Novgorod from 1034 and supervised relations in the north.[17]

Later in Yaroslav's reign, around c.1035, Ingvar the Far-Travelled, Anund Jakob's jarl, sent Swedish soldiers into Kievan Rus due to Olof's son wanting to assist his father's ally Yaroslav in his wars against the Pechenegs and Byzantines. Later, in c.1041 Anund Jakob tried to reestablish Swedish control over the Eastern trade routes and reopen them.[18] The Georgian annals report 1000 men coming into Georgia but the original force was likely much larger, around 3,000 men.[19]

Ingvar's fate is unknown, but he was likely captured in battle during the Byzantine campaigns or killed, supposedly in 1041. Only one ship returned to Sweden, according to the legend.[20]

Campaign against Byzantium

Yaroslav presented his second direct challenge to Constantinople in 1043, when a Rus' flotilla headed by one of his sons appeared near Constantinople and demanded money, threatening to attack the city otherwise. Whatever the reason, the Greeks refused to pay and preferred to fight. The Rus' flotilla defeated the Byzantine fleet but was almost destroyed by a storm and came back to Kiev empty-handed.[21]

Protecting the inhabitants of the Dnieper from the Pechenegs

To defend his state from the Pechenegs and other nomadic tribes threatening it from the south he constructed a line of forts, composed of Yuriev, Bohuslav, Kaniv, Korsun, and Pereyaslavl. To celebrate his decisive victory over the Pechenegs in 1036, who thereafter were never a threat to Kiev, he sponsored the construction of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in 1037.[22]

In 1037 the monasteries of Saint George and Saint Irene were built, named after patron saints of Yaroslav and his wife. Some mentioned and other celebrated monuments of his reign such as the Golden Gate of Kiev were destroyed during the Mongol invasion of Rus', but later restored.

Establishment of law

Yaroslav was a notable patron of literary culture and learning. In 1051, he had a Slavic monk, Hilarion of Kiev, proclaimed the metropolitan bishop of Kiev, thus challenging the Byzantine tradition of placing Greeks on the episcopal sees. Hilarion's discourse on Yaroslav and his father Vladimir is frequently cited as the first work of Old East Slavic literature.

Family life and posterity

In 1019, Yaroslav married Ingegerd Olofsdotter, daughter of Olof Skötkonung, the king of Sweden.[23][24] He gave Ladoga to her as a marriage gift.

Saint Sophia's Cathedral in Kiev houses a fresco representing the whole family: Yaroslav, Irene (as Ingegerd was known in Rus'), their four daughters and six sons.[25] Yaroslav had at least three of his daughters married to foreign princes who lived in exile at his court:

- Elisiv of Kiev to Harald Hardrada[24] (who attained her hand by his military exploits in the Byzantine Empire);

- Anastasia of Kiev to the future Andrew I of Hungary;[24]

- Anne of Kiev married Henry I of France[24] and was the regent of France during their son's minority (she was Yaroslav the Wise's most beloved daughter);

- (possibly) Agatha, wife of Edward the Exile, of the royal family of England, the mother of Edgar the Ætheling and Saint Margaret of Scotland.

Yaroslav had one son from the first marriage (his Christian name being Ilya (?–1020)), and six sons from the second marriage. Apprehending the danger that could ensue from divisions between brothers, he exhorted them to live in peace with each other. The eldest of these, Vladimir of Novgorod, best remembered for building the Cathedral of St. Sophia, Novgorod, predeceased his father. Vladimir succeeded Yaroslav as prince of Novgorod in 1034.[17]

Three other sons—Iziaslav I, Sviatoslav II, and Vsevolod I—reigned in Kiev one after another. The youngest children of Yaroslav were Igor Yaroslavich (1036–1060) of Volhynia and Vyacheslav Yaroslavich (1036–1057) of the Principality of Smolensk. There is almost no information about Vyacheslav. Some documents point out the fact of him having a son, Boris Vyacheslavich, who challenged Vsevolod I sometime in 1077–1078.

Grave

Following his death, the body of Yaroslav the Wise was entombed in a white marble sarcophagus within Saint Sophia's Cathedral. In 1936, the sarcophagus was opened and found to contain the skeletal remains of two individuals, one male and one female. The male was determined to be Yaroslav. The identity of the female was never established. The sarcophagus was again opened in 1939 and the remains removed for research, not being documented as returned until 1964.[26][27]

In 2009, the sarcophagus was opened and surprisingly found to contain only one skeleton, that of a female. It seems the documents detailing the 1964 reinterment of the remains were falsified to hide the fact that Yaroslav's remains had been lost. Subsequent questioning of individuals involved in the research and reinterment of the remains seems to point to the idea that Yaroslav's remains were purposely hidden prior to the German occupation of Ukraine and then either lost completely or stolen and transported to the United States where many ancient religious artifacts were placed to avoid "mistreatment" by the communists.[26][27]

Legacy

Four towns in four countries were named after Yaroslav, three of which he also founded: Yaroslavl (in today's Russia), Jarosław in Poland, Yuryev (now Bila Tserkva, Ukraine), and another Yuryev in place of conquered Tarbatu (now Tartu) between 1030 and 1061 in Estonia. Following the Russian custom of naming military objects such as tanks and planes after historical figures, the helmet worn by many Russian soldiers during the Crimean War was called the "Helmet of Yaroslav the Wise". It was the first pointed helmet to be used by a modern army, even before German troops wore pointed helmets.

In 2008 Yaroslav was placed first (with 40% of the votes) in their ranking of "our greatest compatriots" by the viewers of the TV show Velyki Ukraintsi.[28] Afterwards, one of the producers of The Greatest Ukrainians claimed that Yaroslav had only won because of vote manipulation and that (if that had been prevented) the real first place would have been awarded to Stepan Bandera.[29]

In 2003, a monument to Yaroslav the Wise was erected in Kyiv, Ukraine. The creators of the monument are Boris Krylov and Oles Sydoruk. There is also a Yaroslavska Street in Kiev, and there are various streets named after him in cities throughout Ukraine.

The Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University in Kharkiv is named after him.

Iron Lord was a 2010 feature film based on Yaroslav's early life as a regional prince on the frontier.

On December 12, 2022, on the Constitution Day of the Russian Federation, a monument to Yaroslav the Wise was unveiled at the site near the Novgorod Technical School. The author of the monument is sculptor Sergey Gaev.[30]

Yaroslav's monument in Yaroslavl as depicted on the ₽1000 banknote

Yaroslav's monument in Yaroslavl as depicted on the ₽1000 banknote The ₴2 banknote with a portrait of Yaroslav the Wise.

The ₴2 banknote with a portrait of Yaroslav the Wise. Yaroslav's Rock.

Yaroslav's Rock. The Ukrainian Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

The Ukrainian Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise..jpg.webp) Reverse of the two hryvnia coin, Ukraine, 2018

Reverse of the two hryvnia coin, Ukraine, 2018 A monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kyiv

A monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kyiv Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kyiv

Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kyiv Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kharkiv

Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in Kharkiv Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in the city of Bila Tserkva

Monument to Yaroslav the Wise in the city of Bila Tserkva

Veneration

Yaroslav the Wise | |

|---|---|

Yaroslav the Wise's consolidation of Kiev and Novgorod as depicted at Zoloti Vorota mosaics | |

| Holy Grand Prince,[31] Equal to the Apostles | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholicism[32] Eastern Orthodox Church[33] |

| Canonized | February 3, 2016, Moscow by Bishops' Council of the Russian Orthodox Church[33] |

| Major shrine | Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv |

| Feast | 20 February[33] |

| Attributes | Grand Prince's robes, sword, church model, book or scroll[31] |

| Patronage | Statesmen, Judges, Jurists, Prosecutors, Temple Builders, Librarians, Research, Scientists, Teacher, Students, Kievans[34] |

Yaroslav was at the earliest named a saint by Adam of Bremen in his "Deeds of Bishops of the Hamburg Church" in 1075, but he was not formally canonized. On 9 March 2004, on his 950th death anniversary he was included in the calendar of saints of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). On 8 December 2005, Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow added his name to the Menologium as a local saint.[35] On 3 February 2016, the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church held in Moscow established church-wide veneration of Yaroslav as a local saint.[33]

Notes

- Sometimes spelled Iaroslav; Old East Slavic: Ꙗрославъ Володимѣровичъ, romanized: Jaroslavŭ Volodiměrovičŭ; Russian: Ярослав Владимирович; Ukrainian: Ярослав Володимирович, romanized: Yaroslav Volodymyrovych; Old Norse: Jarizleifr Valdamarsson[1]

- Russian: Ярослав Мудрый, IPA: [jɪrɐˈslaf ˈmudrɨj]; Ukrainian: Ярослав Мудрий, romanized: Yaroslav Mudryi

- Old East Slavic: Гюрьгi, romanized: Gjurĭgì

References

- Olafr svænski gifti siðan Ingigierði dottor sina Iarizleifi kononge syni Valldamars konongs i Holmgarðe (Fagrskinna ch. 27). Also known as Jarisleif I. See Google books

- "Yaroslav I (prince of Kiev) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Apr., 1929), 177.

- Perkhavko VB, Sukharev Yu. V. Warriors of Russia IX-XIII centuries. - M .: Veche, 2006. - P. 64. - ISBN 5-9533-1256-3.

- Arrignon J. —P. Les relations diplomatiques entre Bizance et la Russie de 860 à 1043 // Revue des études slaves. - 1983 .-- T. 55 . - S. 133-135 .

- Kuzmin A. G. Initial stages of the Old Russian annals. - M .: Press of Moscow State University, 1977. - pp. 275-276. Archived March 4, 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kostomarov, Mykola. Russian history in the biographies of its main figures. - M. , 1991 .-- S. 8.

- Kuzmin A. G. Yaroslav the Wise // Great statesmen of Russia. - M. , 1996 .-- S. 26.

- Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, 178.

- Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, 179.

- "Princes Boris and Gleb". 2008-10-07. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, 180.

- Uplysning uti konung Anund Jacobs Historia utur Ryska Handlingar in Kongl. Vitterhets Historie och Antiquitets Akademiens Handlingar, Stockholm 1802 p. 61

- Pritsak, O. (1981). The origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 412

- Snorre Sturluson, Nordiska kungasagor. Vol. II. Stockholm: Fabel, 1992, pp. 89-95 (Olav den heliges saga, Chapters 72-80).

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 59, 60. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia, 980-1584 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780521859165.

- "Vittfarne expedition - Viking-Nevo".

- "Vikings… in Georgia?".

- "Yngvars saga víðförla".

- Plokhy (December 2015). The gates of Europe : a history of Ukraine. Basic Books. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-465-05091-8.

- "Saint Sophia's Cathedral: Sarcophagus of Prince Yaroslav the Wise", Atlas Obscura, retrieved 10 December 2022

- Winroth, Anders (2016). The age of the Vikings. Princeton. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-691-16929-3. OCLC 919479468.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, 181-182.

- Andrzej Poppe: Państwo i kościół na Rusi w XI wieku. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1968, p. 65.

- "Таємниці саркофагу Ярослава Мудрого". istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Plokhy, S. (30 May 2017). "Chapter 5: Keys to Kyiv". The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Basic Books.

- Yaroslav the Wise - the Greatest Ukrainian of all times, Inter TV (19 May 2008)

- BBC dragged into Ukraine TV furore, BBC News (5 June 2008)

- "В Великом Новгороде открыли памятник Ярославу Мудрому". tass.ru. 2022-12-12.

- "Благоверный князь Яросла́в Мудрый". azbyka.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- Berit, Ase (December 31, 2010). Lifelines in World History: The Ancient World, The Medieval World, The Early Modern World, The Modern World. Routledge. p. 216. ISBN 978-0765681256.

- "Определение Освященного Архиерейского Собора Русской Православной Церкви об общецерковном прославлении ряда местночтимых святых / Официальные документы / Патриархия.ru". Патриархия.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- "Святой благоверный великий князь Киевский Ярослав Мудрый | Читальный зал". xpam.kiev.ua. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- "Имена святых, упоминаемых в месяцеслове. Имена мужские. Я + Православный Церковный календарь". days.pravoslavie.ru. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

Bibliography

- Hynes, Mary Ellen; Mazar, Peter (1993). Companion to the Calendar: A Guide to the Saints and Mysteries of the Christian Calendar. LiturgyTrainingPublications. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-56854-011-5.

- Martin, Janet (1995). Medieval Russia, 980-1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36276-8.

- Nazarenko, A. V. (2001). Drevniaia Rus' na mezhdunarodnykh putiakh: mezhdistsiplinarnye ocherki kul'turnykh, torgovykh, politicheskikh sviazei IX-XII vekov (in Russian). Moscow: Russian History Institute. ISBN 5-7859-0085-8.

External links

- Akathist to Saint Yaroslav

- Yaroslav the Wise’s Contested Legacy, A Visual Timeline; Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 10, 2022.