Project Kingfisher

Project Kingfisher was a weapons-development program initiated by the United States Navy during the latter part of World War II. Intended to provide aircraft and surface ships with the ability to deliver torpedoes to targets from outside the range of defensive armament, six different missile concepts were developed; four were selected for full development programs, but only one reached operational service.

| Kingfisher | |

|---|---|

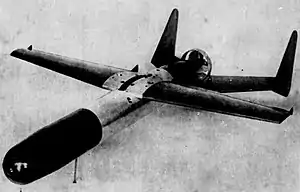

Wind tunnel model of Kingfisher A | |

| Type | Anti-ship missiles Anti-submarine missiles |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1956–1959 |

| Used by | United States Navy |

| Production history | |

| Designer | National Bureau of Standards |

| Designed | 1944–1956 |

Background

Project Kingfisher was initiated in August 1944,[1] in response to the increasing difficulty of torpedo bomber aircraft to successfully complete attacks in the face of the increasing defensive firepower of ships during late World War II. The program was intended to produce standoff delivery systems to allow for the release of torpedoes from outside of the range of enemy defenses, specifically calling for "radar-controlled, subsonic, self-homing, air-borne missiles...to deliver explosive charge [sic] below water line of floating targets".[2] Developed by the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) and the National Bureau of Standards,[3] under the direction of Hugh Latimer Dryden and Edward Conden.[2] Kingfisher was derived from the Pelican and Bat guided-bomb projects,[4] and produced a series of six different missile designs, designated 'A' through 'F', using a variety of payload and guidance options. Of these designs, four – Kingfisher C through F – were determined to be suitable for full development; due to the end of World War II, reducing the priority of the project,[1] development was slowed, with flight testing of early, glider models of Kingfisher taking place in late 1946,[5] and full development of the selected operational versions beginning during 1947.[1]

Variants

Kingfisher A

_layout.jpg.webp)

Kingfisher A, also known as SWOD (Special Warfare Ordnance Device) Mark 11,[1] and later as SWOD Mark 15,[6] was a glide bomb design, intended to carry a Mark 21 Mod 2 torpedo; the weapon was intended for use against surface targets in low-threat environments, where the attacking aircraft did not have to worry about defensive cover from fighter aircraft. Considered to be an interim design before fully powered missiles were available,[1] the Kingfisher A design was used as a basis for glide tests to verify the aerodynamic properties of the Kingfisher family as a whole;[7] these took place late in 1946 using the PB4Y-2 Privateer as a launch aircraft.[5] The Kingfisher A itself was cancelled in early 1947 as no longer being required by the Navy,[4] however the SWOD Mark 15 airframe design was used as a basis for the Kingfisher C.[8]

Kingfisher B

Kingfisher B, or SWOD Mark 21, was of similar design to Kingfisher A, but was designed to be lightweight, the design calling for a weapon only 2/3 the weight of the Bat guided bomb.[9] Its payload was intended to be a plunge bomb, an unguided projectile that upon release would glide briefly along a ballistic trajectory before sinking alongside a target and detonating underwater.[1] Unpowered, it was also cancelled in 1947 as no longer meeting requirements.[4]

Kingfisher C

Kingfisher C was the only member of the Kingfisher family to reach operational service. Developed from the SWOD Mark 15 airframe, and given the definitive designation AUM-N-2 Petrel, construction of the missile was contracted to the Guided Missiles Division of Fairchild Aircraft. As designed, Petrel was essentially a Mark 21 Mod 2 torpedo fitted with flying surfaces and a Fairchild J44 turbojet; the missile had a range of 20 nautical miles (23 mi; 37 km) at Mach 0.5, and used semi-active radar homing for guidance.[8] By the time Petrel entered operational service in 1956,[1] the Mark 41 torpedo had been selected as its definitive warload;[10] launched by the P2V Neptune patrol aircraft, Petrel was withdrawn from operational use by 1959, as it was useless against submerged submarines and the U.S. Navy placed a low priority on defense against surface vessels, considering them an insignificant threat by comparison. [1] Surviving Petrels were repurposed as target drones, which were redesignated as AQM-41A shortly before leaving service in the early 1960s.[8]

Kingfisher D

Kingfisher D was similar in concept to Kingfisher C, but was intended to utilize a new torpedo with a novel dual-purpose propulsion system; a solid-propellant rocket would provide thrust both during the flight of the missile and, following the release of the torpedo, underwater during its terminal run. Given the designation AUM-N-4 Diver, the torpedo's propulsion system proved too complex to successfully develop, and the missile was subsequently cancelled.[1]

Kingfisher E

The only surface-launched variant of the Kingfisher family, Kingfisher E evolved into the SUM-N-2 Grebe anti-submarine missile, intended to deliver a Mark 41 torpedo at ranges of up to 5,000 yards (2.8 mi; 4.6 km) from the launching ship. Construction of Grebe was contracted to the Goodyear Aircraft Company; it was powered by a solid-propellant rocket in its base version, while pulsejet-powered variants were planned to extend the range of the weapon to 40,000 yards (23 mi; 37 km). Flight testing of the missile began in 1950, but it was soon cancelled as sonar systems of the time were incapable of detecting targets at sufficient range to utilize the full capabilities of the missile, rendering it impractical for operational use.[1]

Kingfisher F

Kingfisher F was in some respects a powered version of the Kingfisher B;[1] the missile's intended payload was, like Kingfisher B, a plunge bomb,[11] and the missile was fitted with a pulsejet engine for a range of up to 20 miles (32 km) from its launching aircraft at a speed of Mach 0.7, with guidance via active radar homing.[12] Built by McDonnell Aircraft and given the designation AUM-N-6 Puffin, the missile began flight testing in 1948,[1] and was considered for carriage by United States Air Force bombers as well as U.S. Navy aircraft.[13] Trials demonstrated, however, that Puffin did not meet the Navy's changing requirements, and it was cancelled in October 1949.[1]

Aftermath

Although Project Kingfisher largely failed to result in the operational weapons it had been intended to produce, with only Kingfisher C, the AUM-N-2 Petrel, seeing operational service,[1] much was learned about the issues of aerodynamics and control of guided weapons; while the U.S. Navy chose to use fully ballistic rocket-powered weapons for antisubmarine use, developing the RUR-5 ASROC as its standard anti-submarine missile,[14] the concept of an unpiloted torpedo-carrying aircraft-type missile was developed by other nations, with the French Malafon missile and Australian Ikara being markedly similar in concept to the Kingfisher E/Grebe.[15]

See also

- GT-1 (missile), glide torpedo similar in concept to Kingfisher A

References

Citations

- Friedman 1982, p. 203.

- Dryden and Condon 1947, Abstract

- Ordway and Wakeford 1960, p. 122.

- Dryden and Condon 1947, p. 2.

- Dryden and Condon 1946, frontispiece

- Dryden and Conden 1946, frontispiece and p.7.

- Dryden and Condon 1947, pp. 5–6

- Parsch 2005

- Parsch 2004

- Freidman 1982, p. 119.

- Dryden and Condon 1947, p. 4.

- Parsch 2003

- Yenne 2006, p. 25.

- Friedman 1982, p. 127.

- Friedman 1986, p. 82.

Bibliography

- Dryden, Hugh L.; E. U. Condon (December 1946). Quarterly Progress Report No 1 for Period Ending Dec. 31, 1946 on Project Kingfisher (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- Dryden, Hugh L.; E. U. Condon (March 1947). Quarterly Progress Report No 2 for Period Ending March 31, 1947 on Project Kingfisher (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- Friedman, Norman (1982). U.S. Naval Weapons: Every gun, missile, mine, and torpedo used by the U.S. Navy from 1883 to the present day. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-735-7.

- Friedman, Norman (1986). The Postwar Naval Revolution. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-8702-1952-8.

- Ordway, Frederick Ira; Ronald C. Wakeford (1960). International Missile and Spacecraft Guide. New York: McGraw-Hill. ASIN B000MAEGVC.

- Parsch, Andreas (6 January 2003). "NBS/McDonnell AUM-N-6 Puffin". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Appendix 1: Early Missiles and Drones. Designation-Systems. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- Parsch, Andreas (16 June 2004). "SWOD Series". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Appendix 1: Early Missiles and Drones. Designation-Systems. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- Parsch, Andreas (17 September 2005). "Fairchild AUM-N-2/AQM-41 Petrel". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles. Designation-Systems. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- Yenne, Bill (2006). Secret Gadgets and Strange Gizmos: High-Tech (and Low-Tech) Innovations of the U.S. Military. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0760321157.