Grey-faced petrel

The grey-faced petrel (Pterodroma gouldi) is a petrel endemic to the North Island of New Zealand. In New Zealand it is also known by its Māori name ōi and (along with other species such as the sooty shearwater) as a muttonbird.[2]

| Grey-faced petrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| East of the Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Pterodroma |

| Species: | P. gouldi |

| Binomial name | |

| Pterodroma gouldi (Hutton, 1869) | |

| |

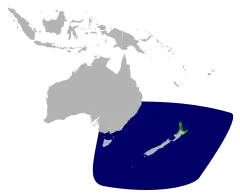

Estimated at-sea distribution Breeding grounds | |

Taxonomy

This species was formerly treated as a subspecies of the great-winged petrel (Pterodroma macroptera) but has been recognized as a separate species since 2014.[1] Research published in 2016 supports the conclusion that P. gouldi should be treated as a separate species.[3]

Description

Grey-faced petrels are large birds, with a body length of 42–45 cm and weighing on average 550 grams (19 oz).[4] They have a dark black-brown colouration, similar to that of the black-footed albatross, with a black bill and pale grey to buff feathers at the base of the bill and throat. The wings are long and enable a buoyant style of flight.[1] Grey-faced petrels are easily confused with Great-winged petrel (Pterodroma macroptera) where their ranges overlap in the Tasman Sea, as these species are morphologically very similar.

Distribution

The grey-faced petrel breeds only in the north of North Island, New Zealand. Colonies are largely found on offshore islands, although small remnant populations exist on the mainland at several sites, and birds are successfully breeding in areas with sufficient control of invasive mammalian predators such as rats, cats, and stoats. The largest breeding colony is found on Moutohora Island, with an estimated 95,000 breeding pairs.[5] Outside of the breeding season, individuals range over the subtropical southwest Pacific Ocean, including Australia and Norfolk Island, keeping mainly in the area between 25 and 50 degrees south. Vagrants may occasionally enter Antarctic waters.[1]

Behaviour and ecology

.jpg.webp)

Breeding

The first grey-faced petrels begin returning to the colonies from mid-March but most birds don't start cleaning out their breeding burrows until April. Courtship peaks from late-April to mid-May. The breeding pair then depart on a pre-laying exodus that ranges from 50 to 70 days for females as they form their large single egg. The first eggs are laid from mid-June but laying peaks in the first 10 days of July, with the last eggs laid in late July.[6] Incubation lasts for about 55 days, a responsibility shared by both parents - swapping over about every 17 days.[6] Males do two long shifts and females one long shift and typically return close to egg hatching. Chicks are left alone in burrows by day from 1–3 days of age. The parents may travel distances of up to 600 km in order to feed their offspring.[7] The chick will be fed by the parents for about 120 days before fledging in December or January.[6] After breeding the adults mostly migrate across to the seas off eastern and southern Australia to carry out their annual feather moult.

Food and feeding

Grey-faced petrels typically hunt squid, fish, and crustaceans, but will sometimes scavenge this food.[7] Grey-faced petrels mostly hunt at night, and as most of their prey are bioluminescent, it is suggested that they use these light cues to hunt.[7][8]

Threats and conservation

Grey-faced petrels have a considerably large population and range, and so are listed as least concern by the IUCN.[1] Furthermore, it is listed as Not Threatened under the New Zealand Threat Classification System due to population increases.[9] One of the largest threats to grey-faced petrels is at breeding grounds, where they are predated on by introduced mammals such as Norway rats.[10] Unattended eggs and young/weak chicks are particularly susceptible to predation, which can impact breeding success rates at colonies.[10] Furthermore, burrowing animals such as rabbits can compete and interfere with grey-faced petrel burrows, which may lead to the birds abandoning them.[10] However, pest eradication projects, such as on Moutohora Island, have allowed some of these colonies to flourish.[5][10]

Town lights have been known to attract some young grey-faced petrels, possibly confusing the artificial light for bioluminescent prey.[8]

Relationship to humans

In New Zealand some Māori iwi, such as Ngāti Awa and the Hauraki iwi, have customary rights to harvest grey-faced petrel chicks.[11] In the middle of the 20th century, a rahui (ban) on harvesting was put in place by these iwi due to declining population numbers.[12] However, in light of population recoveries, harvesting has started to resume.[11] Research has been undertaken to identify safe harvest numbers that will not harm colony populations.[11][12]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Pterodroma gouldi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T45048990A132667566. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T45048990A132667566.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Taylor, G. A. (2013). "Grey-faced petrel". New Zealand Birds Online. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- Wood, Jamie R.; Lawrence, Hayley A.; Scofield, R. Paul; Taylor, Graeme A.; Lyver, Phil O'B.; Gleeson, Dianne M. (May 2016). "Morphological, behavioural, and genetic evidence supports reinstatement of full species status for the grey-faced petrel, (Procellariiformes: Procellariidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1111/zoj.12432.

- "Grey-faced petrel | New Zealand Birds Online". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- Imber, M. J.; Harrison, Malcolm; Wood, Saskia E.; Cotter, Reg N. (2003). "An estimate of numbers of grey-faced petrels (Pterodroma macroptera gouldi) breeding on Moutohora (Whale Island), Bay of Plenty, New Zealand, during 1998-2000". Notornis. 50: 23–36.

- Imber, M. J. (January 1976). "Breeding biology of the grey-faced petrel Pterodroma macroptera govldi". Ibis. 118 (1): 51–64. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1976.tb02010.x.

- Imber, M. J. (October 1973). "The Food of Grey-Faced Petrels (Pterodroma macroptera gouldi (Hutton)), with Special Reference to Diurnal Vertical Migration of their Prey". Journal of Animal Ecology. 42 (3): 645–662. doi:10.2307/3130. JSTOR 3130.

- Imber, M. J. (December 1975). "Behaviour of petrels in relation to the moon and artificial lights". Notornis. 22: 302–306.

- Robertson, Hugh A.; Baird, Karen; Dowding, John E.; Elliott, Graeme P.; Hitchmough, Rodney A.; Miskelly, Colin M.; McArthur, Nikki; O'Donnell, Colin F. J.; Sagar, Paul M.; Scofield, R. Paul; Taylor, Graeme A. (2017). New Zealand Threat Classification Series (PDF) (Report). 19. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation.

- Imber, Mike; Harrison, Malcolm; Harrison, Jan (2000). "Interactions between petrels, rats and rabbits on Whale Island, and effects of rat and rabbit eradication". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 24 (2): 153–160.

- Jones, Christopher J.; Lyver, Philip O'B.; Davis, Joe; Hughes, Beverly; Anderson, Alice; Hohapata-Oke, John (January 2015). "Reinstatement of customary seabird harvests after a 50-year moratorium". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 79 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1002/jwmg.815.

- Lyver, Phil; Jones, Chris; Whitehead, Amy (June 2012). "The re-establishment of a customary harvest of kuia (grey-faced petrels) by Ngāti Awa, Bay of Plenty". Kararehe Kino. No. 20. Landcare Research. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

Further reading

- "Grey-faced Petrel Pterodroma gouldi". BirdLife Species Factsheet.