Government spending

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments.[1][2] In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual or collective needs of the community, is classed as government final consumption expenditure. Government acquisition of goods and services intended to create future benefits, such as infrastructure investment or research spending, is classed as government investment (government gross capital formation). These two types of government spending, on final consumption and on gross capital formation, together constitute one of the major components of gross domestic product.

| Public finance |

|---|

|

Government spending can be financed by government borrowing, taxes, custom duties, the sale or lease of natural resources, and various fees like national park entry fees or licensing fees.[3] When Governments choose to borrow money, they have to pay interest on the money borrowed.[4] Changes in government spending is a major component of fiscal policy used to stabilize the macroeconomic business cycle.

Public expenditure is spending made by the government of a country on collective or individual needs and wants of public goods and public services, such as pension, healthcare, security, education subsidies, emergency services, infrastructure, etc.[5] Until the 19th century, public expenditure was limited due to laissez faire philosophies. In the 20th century, John Maynard Keynes argued that the role of public expenditure was pivotal in determining levels of income and distribution in the economy. Public expenditure plays an important role in the economy as it establishes fiscal policy and provides public goods and services for households and firms.

Theories of public expenditure

Several theories of taxation exist in public economics. Governments at all levels (national, regional and local) need to raise revenue from a variety of sources to finance public-sector expenditures. The details of taxation are guided by two principles: who will benefit, and who can pay. Public expenditure means the expenditure on the developmental and non-developmental activity such as construction of roadways and dams, and other activity.

Rules or principles that govern the expenditure policy of the government are called "canons of public expenditure". Economist George Findlay Shirras [6] laid down the following four canons of public expenditure:

- Canon of Benefit – public spending must be done in a manner that it brings greatest social benefits.

- Canon of Economy – it says that economy does not mean miserliness. Public expenditure must be made productively and efficiently.

- Canon of Sanction – public spending should not be made without sanction of an appropriate authority.

- Canon of Surplus – public revenue should exceed government expenditure, this avoiding a deficit. Government must prepare a budget to create a surplus.[7]

Three other canons are:

- Canon of elasticity- it says there should be enough scope in expenditure policy.government should be able to increase or decrease it according to the period.

- Canon of productivity- public expenditure should encourage production efficiency of the economy.

- Canon of equitable distribution - expenditure policy should minimize inequalities and it should be designed in a way to benefit poorer sections.

Principle of maximum social advantage

The criteria and pre-conditions for arriving at this solution are collectively referred to as the principle of maximum social advantage. Taxation (government revenue) and government expenditure are the two tools. Neither of excess is good for the society, it has to be balanced to achieve maximum social benefit. Dalton called this principle as “Maximum Social Advantage” and Pigou termed it as “Maximum Aggregate Welfare”.

Dalton’s Principle of Maximum Social Advantage – maximum satisfaction should be yield by striking a balance between public revenue and expenditure by the government. Economic welfare is achieved when marginal utility of expenditure = marginal disutility of taxation. He explains this principle with reference to

- Maximum Social Benefit (MSB)

- Maximum Social Sacrifice (MSS)[9]

It was introduced by Swedish Economist “Erik Lindahl in 1919”.[10] According to his theory, determination of public expenditure and taxation will happen on the basis of public preferences which they will reveal themselves. Cost of supplying a good will be taken up by the people. The tax that they will pay will be revealed by them according to their capacities.[11]

Macroeconomic fiscal policy

Government spending can be a useful economic policy tool for governments. Fiscal policy can be defined as the use of government spending and/or taxation as a mechanism to influence an economy.[12][13] There are two types of fiscal policy: expansionary fiscal policy, and contractionary fiscal policy. Expansionary fiscal policy is an increase in government spending or a decrease in taxation, while contractionary fiscal policy is a decrease in government spending or an increase in taxes. Expansionary fiscal policy can be used by governments to stimulate the economy during a recession. For example, an increase in government spending directly increases demand for goods and services, which can help increase output and employment. On the other hand, contractionary fiscal policy can be used by governments to cool down the economy during an economic boom. A decrease in government spending can help check inflation.[12] During economic downturns, in the short run, government spending can be changed either via automatic stabilization or discretionary stabilization. Automatic stabilization is when existing policies automatically change government spending or taxes in response to economic changes, without the additional passage of laws.[14][12] A primary example of an automatic stabilizer is Unemployment Insurance, which provides financial assistance to unemployed workers. Discretionary stabilization is when a government takes actions to change government spending or taxes in direct response to changes in the economy. For instance, a government may decide to increase government spending as a result of a recession.[14] With discretionary stabilization, the government must pass a new law to make changes in government spending.[12]

John Maynard Keynes was one of the first economists to advocate for government deficit spending as part of the fiscal policy response to an economic contraction. According to Keynesian economics, increased government spending raises aggregate demand and increases consumption, which leads to increased production and faster recovery from recessions. Classical economists, on the other hand, believe that increased government spending exacerbates an economic contraction by shifting resources from the private sector, which they consider productive, to the public sector, which they consider unproductive.[15]

In economics, the potential "shifting" in resources from the private sector to the public sector as a result of an increase in government deficit spending is called crowding out.[12] The figure to the right depicts the market for capital, otherwise known as the market for loanable funds. The downward sloping demand curve D1 represents demand for private capital by firms and investors, and the upward sloping supply curve S1 represents savings by private individuals. The initial equilibrium in this market is represented by point A, where the equilibrium quantity of capital is K1 and the equilibrium interest rate is R1. If the government increases deficit spending, it will borrow money from the private capital market and reduce the supply of savings to S2. The new equilibrium is at point B, where the interest rate has increased to R2 and the quantity of capital available to the private sector has decreased to K2. The government has essentially made borrowing more expensive and has taken away savings from the market, which "crowds out" some private investment. The crowding out of private investment could limit the economic growth from the initial increase government spending.[14][13]

Composition

Public expenditure can be divided into COFOG (Classification of the Functions of Government) categories. Those categories are

- pensions, subsidies for family and children, unemployment subsidies, R&D (Research and Development) on social protection.

- public health services, medical products, medical appliances and equipment, hospital services, R&D on healthcare.

- executive and legislative organs, financial and fiscal affairs, external affairs, foreign economic aid, public debt transactions, R&D related to general public services

- pre-primary, primary, secondary, tertiary education, R&D on education etc.

- Economic Affairs

- general economic, agriculture, fuel and energy, commercial and labour affairs, forestry, fishing and hunting, mining, manufacturing, transport, communication etc.

- military defence, civil defence, foreign military aid.

- Recreation, culture and religion

- Recreational and sporting services, cultural services, broadcasting and publishing services, religious services etc.

- waste management, pollution abatement, protection of biodiversity and landscape etc.

- Housing and community services

Final consumption

Government spending on goods and services for current use to directly satisfy individual or collective needs of the members of the community is called government final consumption expenditure (GFCE.) It is a purchase from the national accounts "use of income account" for goods and services directly satisfying of individual needs (individual consumption) or collective needs of members of the community (collective consumption). GFCE consists of the value of the goods and services produced by the government itself other than own-account capital formation and sales and of purchases by the government of goods and services produced by market producers that are supplied to households—without any transformation—as "social transfers" in kind.[17]

Government spending or government expenditure can be divided into three primary groups, government consumption, transfer payments, and interest payments.[18]

- Government consumption are government purchases of goods and services. Examples include road and infrastructure repairs, national defence, schools, healthcare, and government workers’ salaries.

- Investments in sciences and strategic technological innovations to serve the public needs.[19]

- Transfer payments are government payments to individuals. Such payments are made without the exchange of good or services, for example Old Age Security payments, Employment Insurance benefits, veteran and civil service pensions, foreign aid, and social assistance payments. Subsidies to businesses are also included in this category.

- Interest payments are the interest paid to the holders of government bonds, such as Saving Bonds and Treasury Bills.

National defense spending

The United States spends vastly more than other countries on national defense. For example, In 2019 the United States approved a budget of 686.1 billion in discretionary military spending,[20] China was second with an estimated 261 billion dollars in military spending.[21] The table below shows the top 10 countries with the largest military expenditures as of 2015, the most recent year with publicly available data. As the table suggests, the United States spent nearly 3 times as much on the military as China, the country with the next largest military spending. The U.S. military budget dwarfed spending by all other countries in the top 10, with 8 out of [8 out of how many? fix this!] countries spending less than $100 billion in 2016. In 2022, the omnibus spending package increased the military budget by another $42 billion further increasing the United States as the largest defense spenders.

| List by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute 2017 Fact Sheet (for 2016)[22] SIPRI Military Expenditure Database[23]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Healthcare and medical research

Research Australia[26] found 91% of Australians think 'improving hospitals and the health system' should be the Australian Government's first spending priority.

Crowding 'in' also[27] happens in university life science research Subsidies, funding and government business or projects like this are often justified on the basis of their positive return on investment. Life science crowding in contrasts with crowding out in public funding of research more widely:[28] "10% increase in government R&D funding reduced private R&D expenditure by 3%...In Australia, the average cost of public funds is estimated to be $1.20 and $1.30 for each dollar raised (Robson, 2005). The marginal cost is probably higher, but estimates differ widely depending on the tax that is increased".

In the US the total investment in medical and health research and development (R&D) in the US had grown by 27% over the five years from 2013 to 2017, and it is led by industry and the federal government. However, the industry accounted for 67% of total spending in 2017, followed by the federal government at 22%. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH) accounted for the lion's share of federal spending in medical and health research in 2017 was $32.4 billion or 82.1%.[29]

Also, academic and research institutions, this includes colleges, and universities, independent research (IRIs), and independent hospital medical research centres also increased spending, dedicating more than $14.2 billion of their own funds (endowment, donations etc.) to medical and health R&D in 2017. Although other funding sources – foundations, state and local government, voluntary health associations and professional societies – accounted for 3.7% of total medical and health R&D expenditure.

On the other hand, global health spending continues to increase and rise rapidly – to US$7.8 trillion in 2017 or about 10% of GDP and $1.80 per capita – up from US£7.6 trillion in 2016. In addition, about 605 of this spending was public and 40% private, with donor funding representing less than 0.2% of the total although the health spending in real terms has risen by 3.79% in a year while global GDP had grown by 3.0%.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the increase in health spending in low-income countries, and it rose by 7.8% a year between 2000 and 2017 while their economy grew by 6.4%, it is explained in the figure. However, the middle-income economies health spending grew more than 6%, and average annual growth in high-income countries was 3.5%, which is about twice as fast as economic growth. In contrast, health spending by the high-income countries continues to represent to be the largest share of global spending, which is about 81%, despite it covers only 16% of world's population; although it down from 87% in 2000. The primary driver of this change in global spending on healthcare is India and China, which they moved to higher-income groups. Furthermore, just over 40% of the world population lived in low-income countries, which is now they dropped to 10%. Moreover, significant spending increment was in upper-middle-income economies population share has more than doubled over the period of, and share of global health spending nearly also doubled due to China and India's vast population joining that group. Unfortunately, all other spending share income groups had declined.[30]

From the continent view, North America, Western Europe, and Oceanic countries have the highest levels of spending, and West Central Asia, and East Africa the lowest, which is followed closely by South Asia, it is explained in the figure.

It is also true that fast economic growth is associated with increased health spending and sustained rapid economic growth between 2000 and 2017. Even more, fast economic growth which is generally associated with the higher government revenues and health spending is mostly located in Asia such as China, India and Indonesia followed by the Middle East and Latin America. In these countries, the real health spending per capita grew by 2.2 times and increased by 0.6 percentage point as per a share of GDP from 2000 to 2017.

Gross fixed capital formation

Government acquisition intended to create future benefits, such as infrastructure investment or research spending, is called gross fixed capital formation, or government investment, which usually is the largest part of the government.[31] Acquisition of goods and services is made through production by the government (using the government's labour force, fixed assets and purchased goods and services for intermediate consumption) or through purchases of goods and services from market producers. In economic theory or in macroeconomics, investment is the amount purchased of goods which are not consumed but are to be used for future production (i.e. capital). Examples include railroad or factory construction.

Infrastructure spending is considered government investment because it will usually save money in the long run, and thereby reduce the net present value of government liabilities.

Spending on physical infrastructure in the U.S. returns an average of about $1.92 for each $1.00 spent on nonresidential construction because it is almost always less expensive to maintain than repair or replace once it has become unusable.[32]

Likewise, government spending on social infrastructure, such as preventative health care, can save several hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the U.S., because for example cancer patients are more likely to be diagnosed at Stage I where curative treatment is typically a few outpatient visits, instead of at Stage III or later in an emergency room where treatment can involve years of hospitalization and is often terminal.[33]

Per capita spending

In 2010 national governments spent an average of $2,376 per person, while the average for the world's 20 largest economies (in terms of GDP) was $16,110 per person. Norway and Sweden expended the most at $40,908 and $26,760 per capita respectively. The federal government of the United States spent $11,041 per person. Other large economy country spending figures include South Korea ($4,557), Brazil ($2,813), Russia ($2,458), China ($1,010), and India ($226).[34] The figures below of 42% of GDP spending and a GDP per capita of $54,629 for the U.S. indicate a total per person spending including national, state, and local governments was $22,726 in the U.S.

Percentage of GDP

.svg.png.webp)

>55% 50–55% 45–50% 40–45% 35–40% 30–35%

This is a list of countries by government spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for the listed countries, according to the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom[35] by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. Tax revenue is included for comparison. These statistics use the United Nations' System of National Accounts (SNA), which measures the government sector differently than the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The SNA counts as government spending the gross cost of public services such as state universities and public hospitals. For example, the SNA counts the entire cost of running the public-university system, not just what legislators appropriate to supplement students' tuition payments. Those adjustments push up the SNA's measure of spending by roughly 4 percent of GDP compared with the standard measure tallied by the BEA.[36]

Public social spending by country

.svg.png.webp)

Public social spending comprises cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes provided by general government (that is central, state, and local governments, including social security funds).[38]

| Country | Public social spending % of GDP |

|---|---|

| 31.7 | |

| 30.6 | |

| 29.2 | |

| 28.9 | |

| 28.8 | |

| 28.0 | |

| 26.7 | |

| 26.4 | |

| 25.4 | |

| 25.0 | |

| 24.1 | |

| 23.9 | |

| 22.4 | |

| 22.3 | |

| 22.2 | |

| 21.5 | |

| OECD | 21.0 |

| 20.7 | |

| 19.7 | |

| 19.6 | |

| 19.5 | |

| 19.4 | |

| 19.4 | |

| 19.0 | |

| 18.8 | |

| 17.2 | |

| 17.0 | |

| 17.0 | |

| 16.0 | |

| 15.7 | |

| 14.4 | |

| 11.2 | |

| 10.1 |

European Union

Public expenditures represented 46.7 percent of total GDP of the European Union in 2018. Countries with the highest percentage of public expenditure were France and Finland with 56 and 53 percent, respectively. The lowest percentage had Ireland with only 25 percent of its GDP. Among the countries of the European Union, the most important function in public expenditure is social protection. Almost 20 percent of GDP of European Union went to social protection in 2018. The highest ratio had Finland and France, both around 24 percent of their GDPs. The country with least social protection expenditure as percent of its GDP was Ireland with 9 percent. The second largest function in public expenditure is expenditure on health. The general government expenditure on health in European Union was over 7 percent of GDP in 2018. The country with highest share of health expenditure in 2018 Denmark with 8.4 percent. The least percentage had Cyprus with 2.7 percent. General public services had 6 percent of total GDP of European Union in 2018, Education around 4.6 percent and all other categories had less than 4.5 percent of the GDP.[16][39]

Research, assessments and transparency

There is research into government spending such as their efficacies or effective design or comparisons to other options as well as research containing conclusions of public spending-related recommendations. Examples of such are studies outlining benefits of participation in bioeconomy innovation[40][41][42] or identifying potential "misallocations"[43] or "misalignments".[44] Often, such spending may be broad – indirect in terms of national interests – such as with human resources/education-related spending or establishments of novel reward systems. In some cases, various goals and expenditures are made public to various degrees, referred to "budget transparency" or "government spending transparency".[45][46][47][48][49]

Informed and optimized allocations

A study suggests "Greater attention to the development of methods and evidence to better inform the allocation of public sector spending between departments" may be needed and that decisions about public spending may miss opportunities to improve social welfare from existing budgets.[50]

Underlying drivers of spending alterations

A study investigated funding allocations for public investment in energy research, development and demonstration reported insights about past impacts of its drivers, that may be relevant to adjusting (or facilitating) "investment in clean energy" "to come close to achieving meaningful global decarbonization". The investigated drivers can be broadly described as crisis responses, cooperations and competitions.[51][52]

Principles and ethics

Studies and organizations have called for systematically applying principles to spending decisions or to take current issues and goals such as climate change mitigation into account in all such decisions. For example, scientists have suggested in Nature that governments should withstand various pressures and influences and "only support agriculture and food systems that deliver on the SDGs (in line with "public funds for public goods")".[53]

Similarly in regard to openness, a campaign by the Free Software Foundation Europe (FSFE) has called for a principle of "Public Money, Public Code" – that software created using taxpayers' money is developed as free and open source software,[54][55] and Plan S calls for a requirement for scientific publications that result from research funded by public grants being published as open access.[56][57][58]

Public sector ethics may also concern government spending,[59] affecting the shares and intentions of government spending or their respective rationales (beyond ethical principles or implications of the contextual socioeconomic structures), as well as corruption or diversion of public funds.[60]

In 2012, following a United States presidential Campaign to Cut Waste, the Office of Management and Budget issued a memorandum to the heads of federal departments and agencies calling for the avoidance of wasteful expenditure, identifying "practical steps" and setting specific targets for reduction of expenditure on travel, conference attendance and expense, real property and fleet management.[61]

Other areas of spending

Science funding

Governments fund various research beyond healthcare and medical research and defense research. Sometimes, relevant funding decision-making makes use of coordinative and prioritizing tools, data or methods, such as evaluated relevances to global issues or international goals or national goals or major causes of human diseases and early deaths (health impacts).[44]

Energy infrastructure

Travel

Although expenditure on ministerial, elected member and staff travel makes up only a small amount of central government expenditure, and the great majority of work trips by officials are undertaken at standard or economy class, the UK's National Audit Office has noted that this is an aspect of expenditure attracting high levels of public interest.[69]

History

Before World War I

At the end of the 19th century average public expenditure was around 10 percent of GDP. In USA it was only 7 percent and in countries like United Kingdom, Germany or Netherlands it did not exceed amount of 10 percent. Australia, Italy, Switzerland and France had public expenditure over 12 percent of GDP. It was considered as a significant involvement of government in economy. This average share of public expenditure increased to almost 12 percent before the start of World War I. Due to the World War I anticipation, the share increased quickly in Austria, France, United Kingdom or Germany.[70]

Effect of World War I and interwar period

The World War I caused a global growth of the public expenditure share in GDP. In United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and France, which were affected a lot by the war, the share of public expenditure even exceeded 25 percent. In interwar period the average share of the public expenditure was still slightly increasing. The United States increased its public expenditure with the New Deal. Other governments also increased public expenditure in order to create more employment. The increase was accelerated by World War II anticipation in the second part of the 30s among European countries. In 1937 the amount of average public expenditure share was between 22 and 23 percent, twice as much as before World War I. However, it is fair to mention that part of this increase of public expenditure share was caused by GDP fall. Most of industrialized countries had its GDP over 15 percent before the World War II. Only Australia, Norway and Spain had less than 15 percent of GDP.[70]

World War II and post-war period

From the start of the World War I until 1960 the average share of public expenditure in GDP increased slowly from 22 to 28 percent. Most of this increase was given by growth of military spending caused by World War II. Spain, Switzerland and Japan had their public expenditure still below 20 percent of their GDPs.[70]

Second half of the 20th century.

The average public expenditure, as a share of GDP, increased rapidly between years 1960 and 1980 from around 28 to 43 percent. No industrial country had this share below 30 percent in 1980. In Belgium, Sweden and Netherlands it was even over 50 percent. In last two decades of 20th century share of public expenditure kept increasing, but the growth significantly slowed down. In 1996 the average public expenditure was around 45 percent, which is in comparison with 1960-1980 period slow increase from year 1980. During 1980-1996 period the public expenditure share even declined in many countries, for example United Kingdom, Belgium, Netherlands etc.[70]

Growth of public expenditure

There are several factors that have led to an enormous increase in public expenditure through the years

1) Defense expenditure due to modernization of defense equipment by the navy, army and air force to prepare the country for war or for prevention causes-for-growth-of-public-expenditure.

2) Population growth – It increases with the increase in population, more of investment is required to be done by government on law and order, education, infrastructure, etc. investment in different fields depending on the different age group is required.

3) Welfare activities – social welfare, pensions, etc.

- Provision of public and utility services – provision of basic public goods given by government (their maintenance and installation) such as transportation.

- Accelerating economic growth – in order to raise the standard of living of the people.

- Price rise – higher price level compels the government to spend an increased amount on purchase of goods and services.[71]

- Increase in public revenue – with the rise in public revenue government is bound to increase the public expenditure.

- International obligation – maintenance of socio-economic obligation, cultural exchange etc. (these are indirect expenses of government)

4) Wars and social crises – fighting amongst people and communities, and prolonged drought or unemployment, earthquake, hurricanes or tornadoes may lead to an increase in public expenditure of a country. This is because it will involve governments to re-plan and allocate resources to finance the reconstruction.

5) Creation of super national organizations – E.g., the United Nations, NATO, European community and other multinational organizations that are responsible for the provision of public goods and services on an international basis, have to be financed out of funds subscribed by member states, thereby adding to their public expenditure.

6) Foreign aid – Acceptance by the richer industrialized countries of their responsibility to help the poor developing countries has channeled some of the increased public expenditure of the donor country into foreign aid programmes.

7) Inflation – This is the general rise in the price level of goods and services. It increases the cost of all activities of the public sector and thus a major factor in growth in money terms of public expenditure

Present

Since the late 1980s, the average public expenditure to GDP ratio is increasing slowly. The only industrialized countries that reduced significantly are New Zealand, Ireland and Norway. One of the reasons is growing skepticism about governmental intervention in the economy.[70]

See also

- Rahn curve

- Open government

- Government operations

- Public expenditure

- Public finance

- Government budget

- Government waste

- Fiscal policy

- Fiscal council

- Sovereign wealth fund

- Tax

- Mandatory spending

- Taxpayers unions

- Eurostat

- Government spending in the United Kingdom

- Government spending in the United States

- List of countries by government spending as percentage of GDP

- Expenditure incidence

References

- "Government | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)". Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Robert Barro and Vittorio Grilli (1994), European Macroeconomics, Ch. 15–16. Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-57764-7.

- "Sources of Federal Government Revenue | U.S. Treasury Data Lab". datalab.usaspending.gov. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- "Borrowing and the Federal Debt". Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Akrani, Gaurav. "Meaning of Public Expenditure". Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- Cambridge University Libraries, Shirras, George Findlay, 1885-1955 (economist), accessed 4 June 2023

- Muley, Ritika (29 January 2016). "Public Expenditure: Causes, Principles and Importance". EconomicsDiscussion.net. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- "Diminishing Marginal Social Benefit Curve". Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Dalton's Principle of Maximum Social Advantage". Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Lindahl tax

- Singh, SK. Voluntary Exchange Theory of Lindhal for Determination of Public expenditure. S. Chand and Company Ltd. pp. 57–59. ISBN 81-219-1091-9.

- Taylor, Timothy (2017). Principles of Macroeconomics: Economics and the Economy (Fourth ed.). Minneapolis: Textbook Media Press. pp. 366–340. ISBN 9780996996334. OCLC 1001342630.

- Gregory, Mankiw (2014). Principles of Economics (Seventh ed.). Stamford, CT: Southwestern Publishing Group. ISBN 9781285165875. OCLC 884664951.

- Jonathan, Gruber (28 December 2015). Public Finance and Public Policy (Fifth ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 9781464143335. OCLC 914290290.

- Irvin, Tucker (2012). Macroeconomics for Today (8th ed.). Mason, OH: Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781133435051. OCLC 830731890.

- "Composition of Public Expenditure in the EU" (PDF).

- F. Lequiller, D. Blades: Understanding National Accounts, Paris: OECD 2006, pp. 127–30

- Acemoglu, Daron (2018). Macroeconomics. David I. Laibson, John A. List (Second ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-13-449205-6. OCLC 956396690.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2018). "The (ir)rational consideration of the cost of science in transition economies". Nature Human Behaviour. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0281-4. PMID 30980055. S2CID 46878093.

- https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/FY2019-Budget-Request-Overview-Book.pdf Archived 13 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/fs_2020_04_milex_0_0.pdf Archived 27 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2016" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Data for all countries from 1988–2016 in constant (2015) USD (pdf)" (PDF). SIPRI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- SIPRI estimate.

- The figures for Saudi Arabia include expenditure for public order and safety and might be slightly overestimated.

- "Research Australia". crm.researchaustralia.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- http://www.nber.org/papers/w15146.pdf Archived 11 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- "Do innovation programs actually increase innovation?". robwiblin.com. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Strong but uneven spending in medical and health R&D across sectors over five-year period". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "WHO | Global Spending on Health: A World in Transition". WHO. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Gross capital formation" Archived 14 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Statistics Explained European Union Statistics Directorate, European Commission

- Cohen, Isabelle; Freiling, Thomas; Robinson, Eric (January 2012). The Economic Impact and Financing of Infrastructure Spending (PDF) (report). Williamsburg, Virginia: Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy, College of William & Mary. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Hogg, W.; Baskerville, N.; Lemelin, J. (2005). "Cost savings associated with improving appropriate and reducing inappropriate preventive care: Cost-consequences analysis". BMC Health Services Research. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-5-20. PMC 1079830. PMID 15755330.

- CIA World Factbook, population data from 2010, Spending and GDP data from 2011. Note: these numbers do not include U.S. state and local government spending which when included bring the per capita spending to $16,755

- "Economic Data and Statistics on World Economy and Economic Freedom". www.heritage.org. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- "Is Government Spending Really 41 Percent of GDP?". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 18 October 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "Social spending Public, % of GDP, 2015". OECD. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2017. OECD data Archived 21 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archive:Evolution of government expenditure by function - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- Hinderer, Sebastian; Brändle, Leif; Kuckertz, Andreas (2021). "Transition to a Sustainable Bioeconomy". Sustainability. 13 (15): 8232. doi:10.3390/SU13158232.

- Trentacoste, Emily M.; Martinez, Alice M.; Zenk, Tim (1 March 2015). "The place of algae in agriculture: policies for algal biomass production". Photosynthesis Research. 123 (3): 305–315. doi:10.1007/s11120-014-9985-8. ISSN 1573-5079. PMC 4331613. PMID 24599393.

- "Man v food: is lab-grown meat really going to solve our nasty agriculture problem?". The Guardian. 29 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Overland, Indra; Sovacool, Benjamin K. (1 April 2020). "The misallocation of climate research funding". Energy Research & Social Science. 62: 101349. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349. ISSN 2214-6296.

- McCullough, J. Mac; Leider, Jonathon P.; Resnick, Beth; Bishai, David (1 July 2020). "Aligning US Spending Priorities Using the Health Impact Pyramid Lens". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (S2): S181–S185. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305645. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 7362694. PMID 32663078.

- H, Deirdre (22 June 2020). "Governments that budget transparently are more likely to spend as they promise". International Budget Partnership. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Ríos, Ana-María; Bastida, Francisco; Benito, Bernardino (September 2016). "Budget Transparency and Legislative Budgetary Oversight: An International Approach". The American Review of Public Administration. 46 (5): 546–568. doi:10.1177/0275074014565020. S2CID 156789855.

- "Budget transparency - OECD". www.oecd.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, Beatriz; Bisogno, Marco (6 August 2021). "The relevance of budget transparency for development". International Review of Administrative Sciences. 89: 239–256. doi:10.1177/00208523211027525. ISSN 0020-8523. S2CID 238764992.

- De Renzio, Paolo; Masud, Harika (July 2011). "Measuring and Promoting Budget Transparency: The Open Budget Index as a Research and Advocacy Tool: MEASURING AND PROMOTING BUDGET TRANSPARENCY". Governance. 24 (3): 607–616. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01539.x.

- Cubi-Molla, Patricia; Buxton, Martin; Devlin, Nancy (1 September 2021). "Allocating Public Spending Efficiently: Is There a Need for a Better Mechanism to Inform Decisions in the UK and Elsewhere?". Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 19 (5): 635–644. doi:10.1007/s40258-021-00648-2. ISSN 1179-1896. PMC 8187139. PMID 34105080.

- "Competition with China a 'driving force' for clean energy funding in the 21st century". University of Cambridge via techxplore.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Meckling, Jonas; Galeazzi, Clara; Shears, Esther; Xu, Tong; Anadon, Laura Diaz (September 2022). "Energy innovation funding and institutions in major economies". Nature Energy. 7 (9): 876–885. Bibcode:2022NatEn...7..876M. doi:10.1038/s41560-022-01117-3. ISSN 2058-7546. S2CID 252272866.

- Eyhorn, Frank; Muller, Adrian; Reganold, John P.; Frison, Emile; Herren, Hans R.; Luttikholt, Louise; Mueller, Alexander; Sanders, Jürn; Scialabba, Nadia El-Hage; Seufert, Verena; Smith, Pete (April 2019). "Sustainability in global agriculture driven by organic farming". Nature Sustainability. 2 (4): 253–255. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0266-6. hdl:2164/13082. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 169223744. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Tonekaboni, Keywan. "Open CoDE: Open-Source für die öffentliche Verwaltung". c't Magazin (in German). Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "Public Money, Public Code". publiccode.eu. Free Software Foundation Europe (FSFE). Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "European countries demand that publicly funded research be free". The Economist. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "Input for the development of the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- "'Plan S' and 'cOAlition S' – Accelerating the transition to full and immediate Open Access to scientific publications". www.coalition-s.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Premchand, A. "Ethical Dimensions of Public Expenditure Management" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Di Fatta, Davide; Musotto, Roberto; Vesperi, Walter (2018). "Government Performance, Ethics and Corruption in the Global Competitiveness Index". Governing Business Systems. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer International Publishing: 141–151. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-66036-3_8. ISBN 978-3-319-66034-9.

- Office of Management and Budget, Memorandum to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies: Promoting Efficient Spending to Support Agency Operations Archived 17 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, M-12-12, published 11 May 2012, accessed 26 May 2023

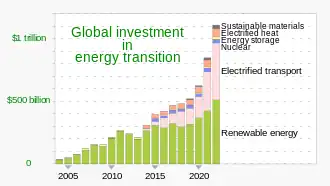

- Catsaros, Oktavia (26 January 2023). "Global Low-Carbon Energy Technology Investment Surges Past $1 Trillion for the First Time". Bloomberg NEF (New Energy Finance). Figure 1. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023.

Defying supply chain disruptions and macroeconomic headwinds, 2022 energy transition investment jumped 31% to draw level with fossil fuels

- Bridle, Richard; Sharma, Shruti; Mostafa, Mostafa; Geddes, Anna (June 2019). "Fossil Fuel to Clean Energy Subsidy Swaps: How to pay for an energy revolution" (PDF). International Institute for Sustainable Development. p. iv. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2019.

- Mazzucato, Mariana; Semieniuk, Gregor (2018). "Financing renewable energy: Who is financing what and why it matters" (PDF). Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 127: 8–22. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.021. ISSN 0040-1625.

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. (2019). "The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate" (PDF). The Lancet. 394 (10211): 1836–1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. PMID 31733928. S2CID 207976337. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- United Nations Development Programme 2020, p. 10.

- Kuzemko, Caroline; Bradshaw, Michael; Bridge, Gavin; Goldthau, Andreas; et al. (2020). "Covid-19 and the politics of sustainable energy transitions". Energy Research & Social Science. 68: 101685. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101685. ISSN 2214-6296. PMC 7330551. PMID 32839704.

- IRENA 2021, p. 5.

- National Audit Office, Investigation into government travel expenditure Archived 26 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine, published 11 March 2015, accessed 26 June 2023

- Public Spending in the 20th Century. 2000. ISBN 0521662915.

- "Causes for Growth of public expenditure". Retrieved 20 February 2012.

Works cited

- IRENA (2021). World Energy Transitions Outlook: 1.5°C Pathway (PDF). ISBN 978-92-9260-334-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2021.

- United Nations Development Programme (2020). Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF) (Report). ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2020.