Putnam County, Tennessee

Putnam County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 79,854.[4] Its county seat is Cookeville.[5] Putnam County is part of the Cookeville, TN Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Putnam County | |

|---|---|

Putnam County Courthouse | |

|

Logo | |

Location within the U.S. state of Tennessee | |

Tennessee's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°08′N 85°30′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 11, 1854 |

| Named for | Israel Putnam[1] |

| Seat | Cookeville |

| Largest city | Cookeville |

| Government | |

| • County executive | Randy Porter (R)[2][3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 403 sq mi (1,040 km2) |

| • Land | 401 sq mi (1,040 km2) |

| • Water | 1.5 sq mi (4 km2) 0.4% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 79,854 |

| • Density | 200/sq mi (80/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 38501, 38502, 38503, 38505, 38506, 38544, 38545, 38548, 39574, 38582 |

| Area code | 931 |

| Congressional district | 6th |

| Website | putnamcountytn |

History

Putnam County is named in honor of Israel Putnam, who was a hero in the French and Indian War and a general in the American Revolutionary War. The county was initially established on February 2, 1842, when the Twenty-fourth Tennessee General Assembly enacted a measure creating the county from portions of Jackson, Overton, Fentress, and White counties.[1]

After the survey was completed by Mounce Gore, the Assembly instructed the commissioners to locate the county seat, to be called "Monticello," near the center of the county. Contending, however, that the formation of Putnam was illegal because it reduced their areas below constitutional limits, Overton and Jackson counties secured an injunction against its continued operation. Putnam officials failed to reply to the complaint, and in the March 1845 term of the Chancery Court at Livingston, Chancellor Bromfield L. Ridley declared Putnam unconstitutionally established and therefore dissolved. The 1854 act reestablishing Putnam was passed after Representative Henderson M. Clements of Jackson County assured his colleagues that a new survey showed that there was sufficient area to form the county. White Plains, near modern Algood, acted as a temporary county seat.[6]

The act specified the "county town" be named "Cookeville" in honor of Richard F. Cooke, who served in the Tennessee Senate from 1851 to 1854, representing at various times Jackson, Fentress, Macon, Overton and White Counties. The act authorized Joshua R. Stone and Green Baker from White County, William Davis and Isaiah Warton from Overton County, John Brown and Austin Morgan from Jackson County, William B. Stokes and Bird S. Rhea from DeKalb County, and Benjamin A. Vaden and Nathan Ward from Smith County, to study the Conner survey and select a spot, not more than two and one-half miles from the center of the county, for the courthouse. The first County Court chose a hilly tract of land, then owned by Charles Crook, for the site.

Putnam County was the site of several saltpeter mines. Saltpeter is the main ingredient of gunpowder and was obtained by leaching the earth from several local caves. Calfkiller Saltpeter Cave, located in the Calfkiller Valley, was a major mining operation, as was Johnson Cave, also located in the Calfkiller Valley. Both caves still contain significant remnants of the mining activity. Several other caves in the county were the site of smaller operations. Most saltpeter mining in Middle Tennessee occurred during the War of 1812 and the Civil War.[7]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 403 square miles (1,040 km2), of which 401 square miles (1,040 km2) is land and 1.5 square miles (3.9 km2) (0.4%) is water.[8]

The county is part of the greater Cumberland River watershed. The southern part of the county is drained by tributaries of the Caney Fork, the northeastern part by tributaries of the Obey River, and the north-central and northwestern parts of the county drain into the Cumberland's Cordell Hull Lake impoundment.[9] The sources of two tributaries of the Caney Fork, the Falling Water River and the Calfkiller River, lie near Monterey in the eastern part of the county.

Adjacent counties

- Overton County (northeast)

- Fentress County (northeast)

- Cumberland County (east)

- White County (south)

- DeKalb County (southwest)

- Smith County (west)

- Jackson County (northwest)

State protected areas

- Burgess Falls State Natural Area (part)

- Burgess Falls State Park (part)

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 8,558 | — | |

| 1870 | 8,698 | 1.6% | |

| 1880 | 11,501 | 32.2% | |

| 1890 | 13,683 | 19.0% | |

| 1900 | 16,890 | 23.4% | |

| 1910 | 20,023 | 18.5% | |

| 1920 | 22,231 | 11.0% | |

| 1930 | 23,759 | 6.9% | |

| 1940 | 26,250 | 10.5% | |

| 1950 | 29,869 | 13.8% | |

| 1960 | 29,236 | −2.1% | |

| 1970 | 35,487 | 21.4% | |

| 1980 | 47,690 | 34.4% | |

| 1990 | 51,373 | 7.7% | |

| 2000 | 62,315 | 21.3% | |

| 2010 | 72,321 | 16.1% | |

| 2020 | 79,854 | 10.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] 2010-2014[4] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 66,782 | 83.63% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 2,161 | 2.71% |

| Native American | 161 | 0.2% |

| Asian | 1,086 | 1.36% |

| Pacific Islander | 33 | 0.04% |

| Other/Mixed | 3,375 | 4.23% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6,256 | 7.83% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 79,854 people, 31,778 households, and 19,395 families residing in the county.

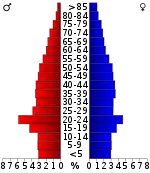

2010 census

As of the census[16] of 2010, there were 72,321 people, 28,930 households, and 18,489 families residing in the county. The population density was 181 people per square mile (70 people/km2). There were 31,882 housing units at an average density of 80 per square mile (31/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 92.0% White, 2.0% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.8% from other races, and 1.5% from two or more races. 5.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 28,930 households, out of which 26.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.70% were married couples living together, 9.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.00% were non-families. 27.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 2.94.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 22.30% under the age of 18, 14.70% from 18 to 24, 27.90% from 25 to 44, 21.90% from 45 to 64, and 13.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.40 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.70 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $33,092, and the median income for a family was $39,553. Males had a median income of $29,243 versus $21,001 for females. The per capita income for the county was $18,892. About 10.30% of families and 16.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.90% of those under age 18 and 16.10% of those age 65 or over.

According to the US Census for 2013 Putnam County has the highest wealth inequality of any United States county with a population of over 65,000.[17]

Education

Cookeville, the largest town in Putnam County, is the home of Tennessee Technological University, which is known for its College of Education's undergraduate and graduate programs, its Engineering program's rigor, its College of Business alumni success, and the creativity of the College of Arts and Sciences. The largest college at Tennessee Tech is the College of Education. The university student population of 11,800 comprises one fourth of the resident population of Cookeville.[18]

The Putnam County school system enrolls approximately 12,000 students in 18 schools throughout the county. All schools are accredited. Cookeville High School is the largest non-metropolitan school in the state and is one of only eight high schools in the state to offer the International Baccalaureate program.

Politics

Putnam County is extremely conservative for a county anchored by a college town (Cookeville, the county seat, is home to Tennessee Technological University). In the 2020 United States presidential election, the Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden, won less than 28% of the vote while Donald Trump, the Republican nominee, won over 70% of the vote.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 23,759 | 70.73% | 9,185 | 27.34% | 649 | 1.93% |

| 2016 | 19,002 | 69.83% | 6,851 | 25.18% | 1,359 | 4.99% |

| 2012 | 17,254 | 67.66% | 7,802 | 30.60% | 444 | 1.74% |

| 2008 | 17,101 | 62.60% | 9,739 | 35.65% | 476 | 1.74% |

| 2004 | 15,637 | 59.14% | 10,566 | 39.96% | 239 | 0.90% |

| 2000 | 11,248 | 50.13% | 10,785 | 48.07% | 405 | 1.80% |

| 1996 | 9,093 | 43.53% | 10,047 | 48.10% | 1,748 | 8.37% |

| 1992 | 7,998 | 37.23% | 10,858 | 50.54% | 2,626 | 12.22% |

| 1988 | 9,547 | 58.62% | 6,606 | 40.56% | 132 | 0.81% |

| 1984 | 8,999 | 54.40% | 7,443 | 45.00% | 99 | 0.60% |

| 1980 | 6,235 | 42.26% | 8,084 | 54.80% | 434 | 2.94% |

| 1976 | 4,079 | 32.10% | 8,485 | 66.77% | 144 | 1.13% |

| 1972 | 6,038 | 60.39% | 3,738 | 37.38% | 223 | 2.23% |

| 1968 | 3,693 | 35.83% | 3,541 | 34.36% | 3,073 | 29.81% |

| 1964 | 2,993 | 32.18% | 6,309 | 67.82% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 4,240 | 48.65% | 4,443 | 50.98% | 32 | 0.37% |

| 1956 | 3,492 | 43.63% | 4,481 | 55.98% | 31 | 0.39% |

| 1952 | 3,183 | 43.73% | 4,096 | 56.27% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 1,879 | 33.77% | 3,134 | 56.33% | 551 | 9.90% |

| 1944 | 1,770 | 38.83% | 2,788 | 61.17% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 1,576 | 34.68% | 2,963 | 65.21% | 5 | 0.11% |

| 1936 | 1,207 | 31.50% | 2,619 | 68.35% | 6 | 0.16% |

| 1932 | 1,281 | 30.40% | 2,911 | 69.08% | 22 | 0.52% |

| 1928 | 1,612 | 42.91% | 2,145 | 57.09% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 1,489 | 37.06% | 2,474 | 61.57% | 55 | 1.37% |

| 1920 | 2,132 | 41.58% | 2,996 | 58.42% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 1,383 | 37.51% | 2,300 | 62.38% | 4 | 0.11% |

| 1912 | 923 | 29.02% | 1,867 | 58.69% | 391 | 12.29% |

See also

References

- Blythe Semmer, "Putnam County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: March 20, 2013.

- "Putnam". County Technical Assistance Service. University of Tennessee. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "Putnam County Election Results August 2, 2018". Putnam County, Tennessee. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Randal William, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for White Plains. Retrieved: September 27, 2009.

- Thomas C. Barr, Jr., "Caves of Tennessee", Bulletin 64 of the Tennessee Division of Geology, 1961.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Watershed Management Approach Archived April 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved: May 10, 2012.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Based on 2000 census data

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- Cohn, Emily (September 23, 2014). "'Here Are the Most Unequal Counties in America'". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Cookeville city, Tennessee". Census.gov. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

External links

- Official site

- Putnam County Library System

- Putnam County Schools

- Putnam County, TNGenWeb - free genealogy resources for the county

- Putnam County at Curlie