Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (/ˈpɪθiəs/; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης Pythéas ho Massaliōtēs; Latin: Pytheas Massiliensis; born c. 350 BC, fl. c. 320–306 BC)[2][1][3] was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, France).[1][4] He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe in about 325 BC, but his account of it, known widely in antiquity, has not survived and is now known only through the writings of others.

Pytheas of Massalia | |

|---|---|

A statue of Pytheas outside the Palais de la Bourse, Marseille | |

| Born | c. 350 BC[1] |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Citizenship | Massaliote |

| Known for | Earliest Greek voyage to Britain, the Baltic, and the Arctic Circle for which there is a record, author of Periplus. |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geography, exploration, navigation |

On this voyage, he circumnavigated and visited a considerable part of modern-day Great Britain and Ireland. He was the first known scientific visitor to see and describe the Arctic, polar ice, and the Celtic and Germanic tribes. He is also the first person on record to describe the midnight sun. The theoretical existence of some Northern phenomena that he described, such as a frigid zone, and temperate zones where the nights are very short in summer and the sun does not set at the summer solstice, was already known. Similarly, reports of a country of perpetual snow and darkness (the country of the Hyperboreans) had reached the Mediterranean some centuries before.

Pytheas introduced the idea of distant Thule to the geographic imagination, and his account of the tides is the earliest one known that suggests the moon as their cause.

Dates

Much of what is known about Pytheas comes from commentary written by historians during the classical period hundreds of years after Pytheas's journeys occurred.[5] Pliny said that Timaeus (born about 350 BC) believed Pytheas' story of the discovery of amber.[6] First century BC Strabo said that Dicaearchus (died about 285 BC) did not trust the stories of Pytheas.[7] That is all the information that survives concerning the date of Pytheas' voyage. Henry Fanshawe Tozer wrote that Pytheas' voyage was about 330 BC, derived from three main sources.[8]

Record

Pytheas described his travels in a work that has not survived; only excerpts remain, quoted or paraphrased by later authors, most familiarly in Strabo's Geographica,[9] Pliny's Natural History and passages in Diodorus of Sicily's history. Most of the ancients, including the first two just mentioned, refer to his work by his name: "Pytheas says …" Two late writers give titles: the astronomical author Geminus of Rhodes mentions τὰ περὶ τοῦ Ὠκεανοῦ (ta peri tou Okeanou), literally "things about the Ocean", sometimes translated as "Description of the Ocean", "On the Ocean" or "Ocean"; Marcianus, the scholiast on Apollonius of Rhodes, mentions περίοδος γῆς (periodos gēs), a "trip around the earth" or περίπλους (periplous), "sail around".

Scholars of the 19th century tended to interpret these titles as the names of distinct works covering separate voyages; for example, Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology hypothesizes a voyage to Britain and Thule written about in "Ocean" and another from Cadiz to the river Don, written about in "Sail Around".[10] As is common with ancient texts, multiple titles may represent a single source, for example, if a title refers to a section rather than the whole. Presently, periplus is recognized as a genre of navigational literature. Mainstream consensus is that there was only one work, "on the Ocean", which was based on a periplus.

Diodorus did not mention Pytheas by name. The association is made as follows:[11] Pliny reported that "Timaeus says there is an island named Mictis … where tin is found, and to which the Britons cross."[12] Diodorus said that tin was brought to the island of Ictis, where there was an emporium. The last link was supplied by Strabo, who said that an emporium on the island of Corbulo in the mouth of the river Loire was associated with the Britain of Pytheas by Polybius.[13] Assuming that Ictis, Mictis and Corbulo are the same, Diodorus appears to have read Timaeus, who must have read Pytheas, whom Polybius also read.

Circumstances of the voyage

Pytheas was the first documented Mediterranean mariner to reach the British Isles.

The start of Pytheas's voyage is unknown. The Carthaginians had closed the Strait of Gibraltar to all ships from other nations. Some historians, mainly of the late 19th century and before, therefore speculated that he must have traveled overland to the mouth of the Loire or the Garonne. Others believed that, to avoid the Carthaginian blockade, he may have stayed close to land and sailed only at night, or taken advantage of a temporary lapse in the blockade.[14]

An alternate theory is that by the 4th century BC, the western Greeks, especially the Massaliotes, were on amicable terms with Carthage. In 348 BC, Carthage and Rome came to terms over the Sicilian Wars with a treaty defining their mutual interests. Rome could use Sicilian markets, Carthage could buy and sell goods at Rome, and slaves taken by Carthage from allies of Rome were to be set free. Rome was to stay out of the western Mediterranean, but these terms did not apply to Massalia, which had its own treaty. During the second half of the 4th century BC, the time of Pytheas' voyage, Massaliotes were presumably free to operate as they pleased; there is, at least, no evidence of conflict with Carthage in any of the sources that mention the voyage.[15]

The early part of Pytheas' voyage was outlined by statements of Eratosthenes that Strabo said are false because taken from Pytheas.[16] Apparently, Pytheas said that tides ended at the "sacred promontory" (Hieron akrōtērion, or Sagres Point), and from there to Gades is said to be 5 days' sail. Strabo complained about this distance, and about Pytheas' portrayal of the exact location of Tartessos. Mention of these places in a journal of the voyage indicates that Pytheas passed through the Straits of Gibraltar and sailed north along the coast of Portugal.

Voyage to Britain

The "circumnavigation"

Strabo reported that Pytheas said he "travelled over the whole of Britain that was accessible".[18] Because there are scant first hand sources available regarding Pytheas's journey, historians have looked at the etymology for clues about the route he took up the north Atlantic. The word epelthein, at root "come upon", does not imply any specific method, and Pytheas did not elaborate.

He did use the word "whole" and he stated a perimetros ("perimeter") of more than 40,000 stadia. Using Herodotus' standard of 600 feet (180 m) for one stadium gives 4,545 miles (7,314 km); however, there is no way to tell which standard foot was in effect. The English foot is an approximation. Strabo wanted to discredit Pytheas on the grounds that 40,000 stadia is outrageously high and cannot be real.

Diodorus Siculus gave a similar number:[19] 42,500 stadia, about 4,830 miles (7,770 km), and explains that it is the perimeter of a triangle around Britain. The consensus has been that he probably took his information from Pytheas through Timaeaus. Pliny gave the circuitus reported by Pytheas as 4,875 Roman miles.[20]

The explorer Fridtjof Nansen explained this apparent fantasy of Pytheas as a mistake of Timaeus.[21] Strabo and Diodorus Siculus never saw Pytheas' work, says Nansen, but they and others read of him in Timaeus. Pytheas reported only days' sail. Timaeus converted days to stadia at the rate of 1,000 per day, a standard figure of the times. However, Pytheas only sailed 560 stadia per day for a total of 23,800, which in Nansen's view is consistent with 700 stadia per degree.

Nansen later states that Pytheas must have stopped to obtain astronomical data. Presumably, the extra time was spent ashore. Using the stadia of Diodorus Siculus, one obtains 42.5 days for the time that would be spent in circumnavigating Britain. (It may have been a virtual circumnavigation; see under Thule below.)

The perimeter, according to Nansen based on the 23,800 stadia, was 2,375 miles (3,822 km). This number is in the neighborhood of what a triangular perimeter ought to be, but it cannot be verified against anything Pytheas may have said, nor was Diodorus Siculus very precise about the locations of the legs. The "perimeter" is often translated as "coastline", but this translation is misleading. The coastline, following all the bays and inlets, is 7,723 miles (12,429 km) (see Geography of the United Kingdom). Pytheas could have travelled any perimeter between that number and Diodorus'. Polybius added that Pytheas said he traversed the whole of Britain on foot,[22] of which he, Polybius, was skeptical. Despite Strabo's conviction of a lie, the perimeter said to have been given by Pytheas is not evidence of it. The issue of what he did say can never be settled until more fragments of Pytheas's writings are found.

Name and description of the British

The first known written use of the word Britain was an ancient Greek transliteration of the original P-Celtic term. It is believed to have appeared within a periplus by Pytheas, but no copies of this work survive. The earliest existing records of the word are quotations of the periplus by later authors, such as those within Strabo's Geographica, Pliny's Natural History and Diodorus of Sicily's Bibliotheca historica.[23] According to Strabo, Pytheas referred to Britain as Bretannikē, which is treated a feminine noun.[24][25][26][27]

"Britain" is most like Welsh Ynys Prydein, "the island of Britain", in which is a P-Celtic cognate of Q-Celtic Cruithne in Irish Cruithen-tuath, "land of the Picts". The base word is Scottish/Irish cruth, Welsh pryd, meaning "form". The British were the "people of forms", with the sense of shapes or pictures,[28] thought to refer to their practice of tattooing or war painting.[29] The Roman word Picti, "the Picts", means "painted".

This etymology suggests Pytheas most likely did not have much interaction with the Irish as their language was Q-Celtic. Rather, Pytheas brought back the P-Celtic form from more geographically accessible regions where Welsh or Breton are spoken presently. Furthermore, some proto-Celtic was spoken over all of Greater Britain, and this particular spelling is prototypical of those more populous regions, but there is no evidence that he distinguished between the peoples of the archipelago.

Diodorus based on Pytheas reported that Britain is cold and subject to frosts, being "too much subject to the Bear", and not "under the Arctic pole", as some translations say.[30] The numerous population of natives, he says, live in thatched cottages, store their grain in subterranean caches and bake bread from it.[30] They are "of simple manners" (ēthesin haplous) and are content with plain fare. They are ruled by many kings and princes who live in peace with each other. Their troops fight from chariots, as did the Greeks in the Trojan War.

The three corners of Britain: Kantion, Belerion and Orkas

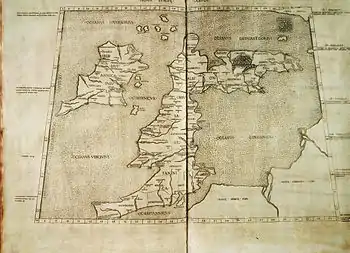

Opposite Europe in Diodorus is the promontory (akrōtērion) of Kantion (Kent), 100 stadia, about 11 miles (18 km), from the land, but the text is ambiguous: "the land" could be either Britain or the continent. Four days' sail beyond that is another promontory, Belerion, which can only be Cornwall, as Diodorus is describing the triangular perimeter and the third point is Orkas, presumably the main island of the Orkney Islands.

The tin trade

The inhabitants of Cornwall were involved in the manufacture of tin ingots. They mined the ore, smelted it and then worked it into pieces in the shape of knuckle-bones, after which it was transported to the island of Ictis by wagon, which could be done at low tide. Merchants that purchased it there packed it on horses for 30 days to the river Rhône, where it was carried down to the mouth. Diodorus said that the inhabitants of Cornwall were civilized in manner and especially hospitable to strangers because of their dealings with foreign merchants.

Scotland

The first written reference to Scotland was in 320 BC by Pytheas, who called the northern tip of Britain "Orcas", the source of the name of the Orkney islands.[31][32]

Thule

Strabo related, taking his text from Polybius, that "Pytheas asserts that he explored in person the whole northern region of Europe as far as the ends of the world."[33] Strabo did not believe it but he explained what Pytheas meant by the ends of the world.[34] Thoulē, he said (now spelled Thule; Pliny the Elder uses Tyle; Vergil references ultima Thule in Georgic I, Line 30, where the ultima refer to the end of the world[35]) is the most northerly of the British Isles. There the circle of the summer tropic is the same as the Arctic Circle (see below on Arctic Circle). Moreover, said Strabo, none of the other authors mention Thule, a fact which he used to discredit Pytheas, but which to moderns indicates Pytheas was the first explorer to arrive there and tell of it.

Thule was described as an island six days' sailing north of Britain, near the frozen sea (pepēguia thalatta, "solidified sea").[36] Pliny added that it had no nights at midsummer when the sun was passing through the sign of the Crab (at the summer solstice),[12] a reaffirmation that it is on the Arctic Circle. He added that the crossing to Thule started at the island of Berrice, "the largest of all", which may be Lewis in the outer Hebrides. If Berrice was in the outer Hebrides, the crossing would have brought Pytheas to the coast of Møre og Romsdal or Trøndelag, Norway, explaining how he managed to miss the Skagerrak. If this is his route, in all likelihood he did not actually circumnavigate Britain, but returned along the coast of Germany, accounting for his somewhat larger perimeter.

Concerning the location of Thule, a discrepancy in data caused subsequent geographers some problems, and may be responsible for Ptolemy's distortion of Scotland. Strabo reported that Eratosthenes places Thule at a parallel 11500 stadia (1305 miles, or 16.4°) north of the mouth of the Borysthenes.[36] The parallel running through that mouth also passes through Celtica and is Pytheas' base line. Using 3700 or 3800 stadia (approximately 420–430 miles or 5.3°–5.4°) north of Marseille for a base line obtains a latitude of 64.8° or 64.9° for Thule, well short of the Arctic Circle. It is in fact the latitude of Trondheim, where Pytheas may have reached land.

A statement by Geminus of Rhodes quotes On the Ocean as saying:[37]

... the Barbarians showed us the place where the sun goes to rest. For it was the case that in these parts the nights were very short, in some places two, in others three hours long, so that the sun rose again a short time after it had set.

Nansen claimed that according to this statement, Pytheas was there in person and that the 21- and 22-hour days must be the customary statement of latitude by length of longest day. He calculates the latitudes to be 64° 32′ and 65° 31′, partially confirming Hipparchus' statement of the latitude of Thule. And yet Strabo said:[34]

Pytheas of Massalia tells us that Thule ... is farthest north, and that there the circle of the summer tropic is the same as the Arctic[38] Circle.

Eratosthenes extended the latitudinal distance from Massalia to Celtica to 5000 stadia (7.1°), placing the base line in Normandy. The northernmost location cited in Britain at the Firth of Clyde is now northern Scotland. To get this country south of Britain to conform to Strabo's interpretation of Pytheas, Ptolemy has to rotate Scotland by 90°.

The 5000 stadia must be discounted: it crosses the Borysthenes upriver near Kyiv rather than at the mouth.[39] It does place Pytheas on the Arctic Circle, which in Norway is south of the Lofoten islands. It seems that Eratosthenes altered the base line to pass through the northern extreme of Celtica. Pytheas, as related by Hipparchus, probably cited the place in Celtica where he first made land. If he used the same practice in Norway, Thule is at least somewhere on the entire northwest coast of Norway from Møre og Romsdal to the Lofoten Islands.

The explorer Richard Francis Burton in his study of Thule stated that it had had many definitions over the centuries. Many more authors have written about it than remembered Pytheas. The question of the location of Pytheas' Thule remains. The latitudes given by the ancient authors can be reconciled. The missing datum required to fix the location is longitude: "Manifestly we cannot rely upon the longitude."[40]

Pytheas crossed the waters northward from Berrice, in the north of the British Isles, but whether to starboard, larboard, or straight ahead is not known. From the time of the Roman Empire all the possibilities were suggested repeatedly by each generation of writers: Iceland, Shetland, the Faroe Islands, Norway and later Greenland. A manuscript variant of a name in Pliny has abetted the Iceland theory: Nerigon instead of Berrice, which sounds like Norway. If one sails west from Norway one encounters Iceland. Burton himself espoused this theory.

The standard texts have Berrice presently, as well as Bergos for Vergos in the same list of islands. The Scandiae islands are more of a problem, as they could be Scandinavia, but other islands had that name as well. Moreover, Procopius says (De Bello Gothico, Chapter 15) that the earlier name of Scandinavia was Thule and that it was the home of the Goths. The fact that Pytheas returned from the vicinity of the Baltic favors Procopius's opinion. The fact that Pytheas lived centuries before the colonization of Iceland and Greenland by European agriculturalists makes them less likely candidates, as he stated that Thule was populated and its soil was tilled.

Concerning the people of Thule Strabo says of Pytheas, but grudgingly:[41]

... he might possibly seem to have made adequate use of the facts as regards the people who live close to the frozen zone, when he says that, ... the people live on millet and other herbs, and on fruits and roots; and where there are grain and honey, the people get their beverage, also, from them. As for the grain, he says, – since they have no pure sunshine – they pound it out in large storehouses, after first gathering in the ears thither; for the threshing floors become useless because of this lack of sunshine and because of the rains.

What he seems to be describing is an agricultural country that used barns for threshing grain rather than the Mediterranean outside floor of sun-baked mud and manufactures a drink, possibly mead.[42]

Encounter with drift ice

.jpg.webp)

After mentioning the crossing (navigatio) from Berrice to Tyle, Pliny made a brief statement that:

A Tyle unius diei navigatione mare concretum a nonnullis Cronium appellatur.

"One day's sail from Thule is the frozen ocean, called by some the Cronian Sea."

The mare concretum appears to match Strabo's pepēguia thalatta and is probably the same as the topoi ("places") mentioned in Strabo's apparent description of spring drift ice, which would have stopped his voyage further north and was for him the ultimate limit of the world. Strabo says:[18][43]

Pytheas also spoke of the waters around Thule and of those places where land properly speaking no longer exists, nor sea nor air, but a mixture of these things, like a "marine lung", in which it was said that earth and water and all things are in suspension as if this something was a link between all these elements, on which one can neither walk nor sail.

The term used for "marine lung" (pleumōn thalattios) appears to refer to jellyfish of the type the ancients called sea-lung. The latter are mentioned by Aristotle in On the Parts of Animals as being free-floating and insensate.[44] They are not further identifiable from what Aristotle says but some pulmones appear in Pliny as a class of insensate sea animal;[45] specifically the halipleumon ("salt-water lung").[46] William Ogle, a major translator and annotator of Aristotle, attributes the name sea-lung to the lung-like expansion and contraction of the Medusae, a kind of Cnidaria, during locomotion.[47] The ice resembled floating circles in the water. The modern English term for this phenomenon is pancake ice.

The association of Pytheas' observations with drift ice has long been standard in navigational literature, including Nathaniel Bowditch's American Practical Navigator, which begins Chapter 33, Ice Navigation, with Pytheas.[48] At its edge, sea, slush, and ice mix, surrounded by fog.

Discovery of the Baltic

Strabo said that Pytheas gave an account of "what is beyond the Rhine as far as Scythia", which he, Strabo, thought was false.[49] In the geographers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire, such as Ptolemy, Scythia stretched eastward from the mouth of the river Vistula; thus Pytheas must have described the Germanic coast of the Baltic Sea; if the statement is true, there are no other possibilities. As to whether he explored it in person, he said that he explored the entire north in person (see under Thule above). As the periplus was a sort of ship's log, he probably did reach the Vistula.

According to The Natural History by Pliny the Elder:[6]

Pytheas said that the Gutones, a people of Germany, inhabited the shores of an estuary of the Ocean called Mentonomon, their territory extending a distance of six thousand stadia; that, at one day's sail from this territory, is the Isle of Abalus, upon the shores of which, amber is thrown up by the waves in spring, it being an excretion of the sea in a concrete form; as, also, that the inhabitants use this amber by way of fuel, and sell it to their neighbours, the Teutones.

The "Gutones" is a simplification of two manuscript variants, Guttonibus and Guionibus, which would be in the nominative case Guttones or Guiones, the Goths in the main opinion.[50] The second major manuscript variant is either Mentonomon (nominative case) or Metuonidis (genitive case). A number of etymologies have been proposed but none very well accepted. Amber is not actually named. It is termed the concreti maris purgamentum, the "frozen sea's leavings" after the springtime melt. Diodorus used ēlektron, the Greek word for amber, the object that gave its name to electricity through its ability to acquire a charge. Pliny presented an archaic opinion, as in his time amber was a precious stone brought from the Baltic at great expense, but the Germans, he said, used it for firewood, according to Pytheas.

"Mentonomon" is unambiguously stated to be an aestuarium or "estuary" of 6000 stadia, which using the Herodotean standard of 600 feet (180 m) per stadium is 681 miles (1,096 km). That number happens to be the distance from the mouth of the Skagerrak to the mouth of the Vistula, but no source says explicitly where the figure was taken. Competing views, however, usually have to reinterpret "estuary" to mean something other than an estuary, as the west of the Baltic Sea is the only body of estuarial water of sufficient length in the region.

Earlier Pliny said that a large island of three days' sail from the Scythian coast called Balcia by Xenophon of Lampsacus is called Basilia by Pytheas.[51] It is generally understood to be the same as Abalus. Based on the amber, the island could have been Heligoland, Zealand, the shores of Bay of Gdansk, Sambia or the Curonian Lagoon, which were historically the richest sources of amber in northern Europe. This is the earliest use of Germania.

Voyage to the Don

Pytheas claimed to have explored the entire north; however, he turned back at the mouth of the Vistula, the border with Scythia. If he had gone on he would have discovered the ancestral Balts. They occupied the lands to the east of the Vistula. In the west they began with the people living around Frisches Haff, Lithuanian Aismarės, "sea of the Aistians", who in that vicinity became the Baltic Prussians.[52] On the east Herodotus called them the Neuri, a name related to Old Prussian narus, "the deep", in the sense of water country. Later Lithuanians would be "the people of the shore". The Vistula was the traditional limit of Greater Germany. Place names featuring *ner- or *nar- are wide-ranging over the vast Proto-Baltic homeland, occupying western Russia before the Slavs.[53]

Herodotus said that the Neuri had Scythian customs, but they were at first not considered Scythian.[54] During the war between the Scythians and the Persian Empire, the Scythians came to dominate the Neuri. Strabo denied that any knowledge of the shores of the eastern Baltic existed. He had heard of the Sauromatai, but had no idea where to place them.[55]

Herodotus had mentioned these Sauromatai as a distinct people living near the Neuri. Pliny the Elder, however, was much better informed. The island of Baunonia (Bornholm), he said lies a days' sail off Scythia, where amber is collected.[51] To him the limit of Germany was the Vistula. In contrast to Strabo, he knew that the Goths live around the Vistula, but these were definitely Germans.

By the time of Tacitus, the Aestii had emerged.[56] The former Scythia was now entirely Sarmatia. Evidently the Sarmatians conquered westward to the Vistula. The Goths moved to the south. That the Balts lived east of the Vistula from remote prehistoric times is unquestioned. The Baltic languages, however, are only known from the 2nd millennium AD. They are known to have developed in tribal contexts, as they were originally tribal. The first mention of any tribes is in Ptolemy's description of European Sarmatia, where the main Prussian tribes are mentioned for the first time.[57]

In Tacitus, only the language of the Aestii is mentioned. Strabo distinguished the Venedi, who were likely Slavs. From these few references, which are the only surviving evidence apart from glottochronology[58] and place name analysis, it would seem that the Balts of Pytheas' time were well past the Common Balto-Slavic stage, and likely spoke a number of related dialects. By turning back at what he thought was the limit of Germany, he not only missed the Balts, but did not discover that more Germans, the Goths, had moved into the Baltic area.

Polybius related: "... on his return thence (from the north), he traversed the whole of the coast of Europe from Gades to the Tanais."[59] Some authors consider this leg a second voyage, as it does not seem likely he would pass by Marseille without refitting and refreshing the crew. It is striking that he encountered the border of Scythia, turned around, and went around Europe counter-clockwise until he came to the southern side of Scythia on the Black Sea. It is possible to speculate that he may have hoped to circumnavigate Europe, but the sources do not say. In other, even more speculative interpretations, Pytheas returned north and the Tanais is not the Don but is a northern river, such as the Elbe.[10]

Measurements of latitude

Latitude by the altitude of the Sun

In discussing the work of Pytheas, Strabo typically used direct discourse: "Pytheas says ..." In presenting his astronomical observations, he changed to indirect discourse: "Hipparchus said that Pytheas says ..." either because he never read Pytheas' manuscript (because it was not available to him) or in deference to Hipparchus, who appears to have been the first to apply the Babylonian system of representing the sphere of the Earth by 360°.[60]

Strabo used the degrees, based on Hipparchus.[61] Neither say that Pytheas did. Nevertheless, Pytheas did obtain latitudes, which, according to Strabo, he expressed in proportions of the gnōmōn ("index"), or trigonometric tangents of angles of elevation to celestial bodies. They were measured on the gnōmōn, the vertical leg of a right triangle, and the flat leg of the triangle. The imaginary hypotenuse looked along the line of sight to the celestial body or marked the edge of a shadow cast by the vertical leg on the horizontal leg.

Pytheas took the altitude of the Sun at Massalia at noon on the longest day of the year and found that the tangent was the proportion of 120 (the length of the gnōmōn) to 1/5 less than 42 (the length of the shadow).[62] Hipparchus, relying on the authority of Pytheas (says Strabo[63]), states that the ratio is the same as for Byzantium and that the two therefore are on the same parallel. Nansen and others prefer to give the cotangent 209/600,[64] which is the inverse of the tangent, but the angle is greater than 45° and it is the tangent that Strabo states. His number system did not permit him to express it as a decimal but the tangent is about 2.87.

It is unlikely that any of the geographers could compute the arctangent, or angle of that tangent. Moderns look it up in a table. Hipparchos is said to have had a table of some angles. The altitude, or angle of elevation, is 70° 47′ 50″[64] but that is not the latitude.

At noon on the longest day the plane of longitude passing through Marseille is exactly on edge to the Sun. If the Earth's axis were not tilted toward the Sun, a vertical rod at the equator would have no shadow. A rod further north would have a north–south shadow, and as an elevation of 90° would be a zero latitude, the complement of the elevation gives the latitude. The Sun is even higher in the sky due to the tilt. The angle added to the elevation by the tilt is known as the obliquity of the ecliptic and at that time was 23° 44′ 40″.[64] The complement of the elevation less the obliquity is 43° 13′, only 5′ in error from Marseille's latitude, 43° 18′.[65]

Latitude by the elevation of the north pole

A second method of determining the latitude of the observer measures the angle of elevation of a celestial pole, north in the northern hemisphere. Seen from zero latitude the north pole's elevation is zero; that is, it is a point on the horizon. The declination of the observer's zenith also is zero and therefore so is their latitude.

As the observer's latitude increases (traveling north) so does the declination. The pole rises over the horizon by an angle of the same amount. The elevation at the terrestrial North Pole is 90° (straight up) and the celestial pole has a declination of the same value. The latitude also is 90.[66]

Moderns have Polaris to mark the approximate location of the North celestial pole, which it does nearly exactly. This was not the case in Pytheas' time, due to the precession of the equinoxes. Pytheas reported that the pole was an empty space at the corner of a quadrangle, the other three sides of which were marked by stars.[67] Their identity has not survived but based on calculations these are believed to have been α and κ in Draco and β in Ursa Minor.[68]

Pytheas sailed northward with the intent of locating the Arctic Circle and exploring the "frigid zone" to the north of it at the extreme of the Earth. He did not know the latitude of the circle in degrees. All he had to go by was the definition of the frigid zone as the latitudes north of the line where the celestial arctic circle was equal to the celestial Tropic of Cancer, the tropikos kuklos (refer to the next subsection). Strabo's angular report of this line as being at 24° may well be based on a tangent known to Pytheas, but he did not say that. In whatever mathematical form Pytheas knew the location, he could only have determined when he was there by taking periodic readings of the elevation of the pole (eksarma tou polou in Strabo and others).

Today the elevation can be obtained easily on ship with a quadrant. Electronic navigational systems have made even this simple measure unnecessary. Longitude was beyond Pytheas and his peers, but it was not of as great a consequence, because ships seldom strayed out of sight of land. East–west distance was a matter of contention to the geographers; they are one of Strabo's most frequent topics. Because of the gnōmōn north–south distances were accurate often to within a degree.

It is unlikely that any gnōmōn could be read accurately on the pitching deck of a small vessel at night. Pytheas must have made frequent overnight stops to use his gnōmōn and talk to the natives, which would have required interpreters, probably acquired along the way. The few fragments that have survived indicate that this material was a significant part of the periplus, possibly kept as the ship's log. There is little hint of native hostility; the Celts and the Germans appear to have helped him, which suggests that the expedition was put forward as purely scientific. In any case all voyages required stops for food, water and repairs; the treatment of voyagers fell under the special "guest" ethic for visitors.

Location of the Arctic Circle

The ancient Greek view of the heavenly bodies on which their navigation was based was imported from Babylonia by the Ionian Greeks, who used it to become a seafaring nation of merchants and colonists during the Archaic period in Greece. Massalia was an Ionian colony. The first Ionian philosopher, Thales, was known for his ability to measure the distance of a ship at sea from a cliff by the very method Pytheas used to determine the latitude of Massalia, the trigonometric ratios.

The astronomic model on which ancient Greek navigation was based, which is still in place today, was already extant in the time of Pytheas, the concept of the degrees only being missing. The model[69] divided the universe into a celestial and an earthly sphere pierced by the same poles. Each of the spheres were divided into zones (zonai) by circles (kukloi) in planes at right angles to the poles. The zones of the celestial sphere repeated on a larger scale those of the terrestrial sphere.

The basis for division into zones was the two distinct paths of the heavenly bodies: that of the stars and that of the Sun and Moon. Astronomers know today that the Earth revolving around the Sun is tilted on its axis, bringing each hemisphere now closer to the Sun, now further away. The Greeks had the opposite model, that the stars and the Sun rotated around the Earth. The stars moved in fixed circles around the poles. The Sun moved at an oblique angle to the circles, which obliquity brought it now to the north, now to the south. The circle of the Sun was the ecliptic. It was the center of a band called the zodiac on which various constellations were located.

The shadow cast by a vertical rod at noon was the basis for defining zonation. The intersection of the northernmost or southernmost points of the ecliptic defined the axial circles passing through those points as the two tropics (tropikoi kukloi, "circles at the turning points") later named for the zodiacal constellations found there, Cancer and Capricorn. During noon of the summer solstice (therinē tropē) rods there cast no shadow.[70] The latitudes between the tropics were called the torrid zone (diakekaumenē, "burned up").

Based on their experience of the Torrid Zone south of Egypt and Libya, the Greek geographers judged it uninhabitable. Symmetry requires that there be an uninhabitable Frigid Zone (katepsugmenē, "frozen") to the north and reports from there since the time of Homer seemed to confirm it. The edge of the Frigid Zone ought to be as far south from the North Pole in latitude as the Summer Tropic is from the Equator. Strabo gives it as 24°, which may be based on a previous tangent of Pytheas, but he does not say. The Arctic Circle would then be at 66°, accurate to within a degree.[71]

Seen from the equator the celestial North Pole (boreios polos) is a point on the horizon. As the observer moves northward the pole rises and the circumpolar stars appear, now unblocked by the Earth. At the Tropic of Cancer the radius of the circumpolar stars reaches 24°. The edge stands on the horizon. The constellation of mikra arktos (Ursa Minor, "little bear") was entirely contained within the circumpolar region. The latitude was therefore called the arktikos kuklos, "circle of the bear". The terrestrial Arctic Circle was regarded as fixed at this latitude. The celestial Arctic Circle was regarded as identical to the circumference of the circumpolar stars and therefore a variable.

When the observer is on the terrestrial Arctic Circle and the radius of the circumpolar stars is 66° the celestial Arctic Circle is identical to the celestial Tropic of Cancer.[72] That is what Pytheas means when he says that Thule is located at the place where the Arctic Circle is identical to the Tropic of Cancer.[34] At that point, on the day of the Summer Solstice, the vertical rod of the gnōmōn casts a shadow extending in theory to the horizon over 360° as the Sun does not set. Under the pole the Arctic Circle is identical to the Equator and the Sun never sets but rises and falls on the horizon. The shadow of the gnōmōn winds perpetually around it.

Latitude by length of longest day, and by Sun's elevation on shortest day

Strabo used the astronomical cubit (pēchus, the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the little finger) as a measure of the elevation of the sun. The term "cubit" in this context is obscure; it has nothing to do with distance along either a straight line or an arc, does not apply to celestial distances, and has nothing to do with the gnōmōn. Hipparchus borrowed this term from Babylonia, where it meant 2°. They in turn took it from ancient Sumer so long ago that if the connection between cubits and degrees was known in either Babylonia or Ionia it did not survive. Strabo stated degrees in either cubits or as a proportion of a great circle. The Greeks also used the length of day at the summer solstice as a measure of latitude. It is stated in equinoctial hours (hōrai isēmerinai), one being 1/12 of the time between sunrise and sunset on an equinox.

Based partly on data taken from Pytheas, Hipparchus correlated cubits of the Sun's elevation at noon on the winter solstice, latitudes in hours of a day on the summer solstice, and distances between latitudes in stadia for some locations.[73] Pytheas had proved that Marseille and Byzantium were on the same parallel (see above). Hipparchus, through Strabo,[74] added that Byzantium and the mouth of the Borysthenes, today's Dnieper, were on the same meridian and were separated by 3700 stadia, 5.3° at Strabo's 700 stadia per a degree of meridian arc. As the parallel through the river-mouth also crossed the coast of "Celtica", the distance due north from Marseille to Celtica was 3700 stadia, a baseline from which Pytheas seems to have calculated latitude and distance.[75]

Strabo said that Ierne (written Ἰέρνη, meaning Ireland[76]) is under 5000 stadia (7.1°) north of this line. These figures place Celtica around the mouth of the Loire, an emporium for the trading of British tin. The part of Ireland referenced is the vicinity of Belfast. Pytheas then would either have crossed the Bay of Biscay from the coast of Spain to the mouth of the Loire, or reached it along the coast, crossed the English channel from the vicinity of Brest, France to Cornwall, and traversed the Irish Sea to reach the Orkney Islands. A statement of Eratosthenes attributed by Strabo to Pytheas, that the north of the Iberian Peninsula was an easier passage to Celtica than across the Ocean,[77] is somewhat ambiguous: apparently he knew or knew of both routes, but he does not say which he took.

At noon on the winter solstice the Sun stands at 9 cubits and the longest day on the summer solstice is 16 hours at the baseline through Celtica.[78] At 2500 stadia, approximately 283 miles, or 3.6°, north of Celtica, are a people Hipparchus called Celtic, but whom Strabo thought were the British, a discrepancy he might not have noted if he had known that the British were also Celtic. The location is Cornwall. The Sun stands at 6 cubits and the longest day is 17 hours. At 9100 stadia, approximately 1032 miles, north of Marseille, 5400 or 7.7° north of Celtica, the elevation is 4 cubits and the longest day is 18 hours. This location is in the vicinity of the Firth of Clyde.

Here Strabo launched another quibble. Hipparchus, relying on Pytheas, according to Strabo, placed this area south of Britain, but he, Strabo, calculated that it was north of Ireland (Ierne/Ἰέρνη). Pytheas, however, rightly knew what is now Scotland as part of Britain, land of the Picts, even though north of Ireland/Ierne. North of southern Scotland the longest day is 19 hours. Strabo, based on theory alone, states that Ierne is so cold[34] that any lands north of it must be uninhabited. In the hindsight given to moderns Pytheas, in relying on observation in the field, appears more scientific than Strabo, who discounted the findings of others merely because of their strangeness to him. The ultimate cause of his skepticism is simply that he did not believe Scandinavia could exist. This disbelief may also be the cause of alteration of Pytheas' data.

On the tides

Pliny reported that "Pytheas of Massalia informs us, that in Britain the tide rises 80 cubits."[79] The passage does not give enough information to determine which cubit Pliny meant; however, any cubit gives the same general result. If he was reading an early source, the cubit may have been the Cyrenaic cubit, an early Greek cubit, of 463.1 mm, in which case the distance was 37 metres (121 ft). This number far exceeds any modern known tides. The National Oceanography Centre, which records tides at tidal gauges placed in about 55 ports of the UK Tide Gauge Network on an ongoing basis, records the highest mean tidal change between 1987 and 2007 at Avonmouth in the Severn Estuary of 6.955 m (22.82 ft).[80]

The highest predicted spring tide between 2008 and 2026 at that location will be 14.64 m (48.0 ft) on 29 September 2015.[81] Even allowing for geologic and climate change, Pytheas' 80 cubits far exceeds any known tides around Britain. One well-circulated but unevidenced answer to the paradox is that Pytheas was referring to a storm surge.[82] Despite the modern arguments, the fact remains that Pytheas experienced tides that exceeded by far the usual tides in the Mediterranean, and particularly those at Massilia.

Matching fragments of Aëtius in pseudo-Plutarch and Stobaeus[83] attribute the flood tides (πλήμμυραι plēmmurai) to the "filling of the moon" (πλήρωσις τῆς σελήνης plērōsis tēs sēlēnēs) and the ebb tides (ἀμπώτιδες ampōtides) to the "lessening" (μείωσις meiōsis). The words are too ambiguous to make an exact determination of Pytheas' meaning, whether diurnal or spring and neap tides are meant, or whether full and new moons or the half-cycles in which they occur. Different translators take different views.

That daily tides should be caused by full moons and new moons is manifestly wrong, which would be a surprising view in a Greek astronomer and mathematician of the times. He could have meant that spring and neap tides were caused by new and full moons, which is partially correct in that spring tides occur at those times. A gravitational theory (objects fall to the center) existed at the time but Pytheas appears to have meant that the phases themselves were the causes (αἰτίαι aitiai). However imperfect or imperfectly related the viewpoint, Pytheas was the first to associate the tides to the phases of the moon.

Literary influence

Pytheas was a central source of information on the North Sea and the subarctic regions of western Europe to later periods, and possibly the only source. The only ancient authors we know by name who certainly saw Pytheas' original text were Dicaearchus, Timaeus, Eratosthenes, Crates of Mallus, Hipparchus, Polybius, Artemidorus and Posidonius.[84] Notably the list does not include Strabo or Tacitus, though Strabo discussed him and Tacitus may likely have known about his work. Either of the two could have known him through other writers or have read his work in the original.

Strabo, citing Polybius, accused Pytheas of promulgating a fictitious journey he could never have funded, as he was a private individual (idiōtēs) and a poor man (penēs).[33] Markham proposes a possible answer to the funding question:[85] seeing that Pytheas was known as a professional geographer and that north Europe was as yet a question mark to Massalian merchants, he suggests that "the enterprise was a government expedition of which Pytheas was placed in command." In another suggestion the merchants of Marseille sent him out to find northern markets. These theories are speculative but perhaps less so than Strabo's contention that Pytheas was a charlatan just because a professional geographer doubted him.[86]

Strabo did explain his reasons for doubting Pytheas' veracity. Citing numerous instances of Pytheas apparently being far off the mark on details concerning known regions, he said: "however, any man who has told such great falsehoods about the known regions would hardly, I imagine, be able to tell the truth about places that are not known to anybody."[49] As an example he mentioned that Pytheas says Kent is several days' sail from Celtica when it is visible from Gaul across the channel. If Pytheas had visited the place he should have verified it personally.

The objection although partially true is itself flawed. Strabo interjected his own view of the location of Celtica, that it was opposite to Britain, end to end.[49] Pytheas, however, places it further south, around the mouth of the Loire (see above), from which it might justifiably be several days' sail.[87] The people across from Britain in Caesar's time were the Germani in the north and the Belgae in the south. Still, some of the Celtic lands were on the channel and were visible from it, which Pytheas should have mentioned but Strabo implies he did not.

Strabo's other objections are similarly flawed or else completely wrong. He simply did not believe the earth was inhabited north of Ierne. Pytheas however could not then answer for himself, or protect his own work from loss or alteration, so most of the questions concerning his voyage remain unresolved, to be worked over by every generation. To some he was a daring adventurer and discoverer;[88] to others, a semi-legendary blunderer or prevaricator.

The logical outcome of this tendency is the historical novel with Pytheas as the main character and the celebration of Pytheas in poetry beginning as far back as Virgil. The process continues into modern times; for example, Pytheas is a key theme in Charles Olson's Maximus Poems. Details of Pytheas' voyage also serve as the backdrop for Chapter I of Poul Anderson's science fiction novel, The Boat of a Million Years. The Stone Stories trilogy by Mandy Haggith (The Walrus Mutterer, 2018; The Amber Seeker, 2019; The Lyre Dancers, 2020) revolve around Pytheas of Massalia's journeys.

Notes

- Kaplan 2013.

- Cunliffe 2002, p. 2.

- Warmington & Spawforth 2015.

- Stein-Hölkeskamp, Elke; Engels, Johannes; Gärtner, Hans Armin; Albiani, Maria Grazia (2006). "Pytheas". Brill's New Pauly. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e1016010.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2001). The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek. London, England: Penguin Group. pp. 74–76. ISBN 0-7139-9509-2.

- Natural History, Book 37, Chapter 11.

- Geographica Book II.4.2 paragraph 401).

- Tozer, Henry Fanshawe (1897). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: Cambriddge University Press. pp. 152–154..

- Book I.4.2–4 covers the astronomical calculations of Pytheas and calls him a prevaricator. Book II.3.5 excuses his prevarication on the grounds of his being a professional. Book III.2.11 and 4.4, Book IV.2.1 criticises him again, Book IV.4.1 mentions his reference to the Celtic Ostimi. Book IV.5.5 describes Thule. Book VII.3.1 accuses him of using his science to conceal lies.

- Smith 1880, Pytheas.

- Holmes, T. Rice (1907). Ancient Britain and the Invasions of Julius Caesar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 499–500.

Ancient Britain and the Invasions of Julius Caesar.

- Natural History Book IV Chapter 30 (16.104).

- Geographica IV.2.1.

- Whitaker, Ian (December 1981 – January 1982). "The Problem of Pytheas' Thule". The Classical Journal. 77 (2): 148–164. JSTOR 3296920.

- Ebel, Charles (1976). Transalpine Gaul: The Emergence of a Roman Province. Leiden: Brill Archive. pp. 9–15. ISBN 978-90-04-04384-8.

- Geographica III.2.11.

- Tierney, James J. (1959). "Ptolemy's Map of Scotland". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 79: 132–148. doi:10.2307/627926. JSTOR 627926. S2CID 163631018.

- Geographica Book II.4.1.

- Book V chapter 21.

- Natural History Book IV Chapter 30 (16.102).

- Nansen 1911, p. 51.

- Book XXXIV chapter 5, which survives as a fragment in Geographica Book II.4.1.

- Book I.4.2–4, Book II.3.5, Book III.2.11 and 4.4, Book IV.2.1, Book IV.4.1, Book IV.5.5, Book VII.3.1

- Βρεττανική. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Strabo's Geography Book I. Chapter IV. Section 2 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- Strabo's Geography Book IV. Chapter II. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- Strabo's Geography Book IV. Chapter IV. Section 1 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project.

- Thomas, Charles (1997). Celtic Britain. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 82. ISBN 9780500279359.

If we seek a meaning, the favoured view is that it arises from an older word implying 'people of the forms, shapes or depictions' (*kwrt-en-o-).

- Allen, Stephen (2007). Lords of Battle: The World of the Celtic Warrior. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 174.

Pretani is generally believed to mean "painted" or rather "tattooed", likely referring to the use by the Britons of the blue dye extracted from woad. ... it is more likely to be a nickname given them by outsiders ... It may be compared with the word Picti ... which was used by the Romans in the 3rd century AD.

- Siculi, Diodori; L. Rhodoman; G. Heyn; N. Eyring (1798). "Book V, Sections 21–22". In Peter Wesseling (ed.). Bibliothecae Historicae Libri Qui Supersunt: Nova Editio (in Ancient Greek and Latin). Argentorati: Societas Bipontina. pp. 292–297. The section numeration differs somewhat in different translations; the material is to be found near the end of Book V.

- Forsyth, Katherine (2005). "Origins: Scotland to 1100". In Wormald, Jenny (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199601646.

- Aristotle or Pseudo-Aristotle (1955). "On the Cosmos, 393b12". On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos. Translated by Forster, E. S.; Furley, D. J. Harvard University Press. pp. 360–361. at the Open Library Project. DjVu

- Geographica II.4.2.

- Geographica II.5.8.

- Burton 1875, p. 2

- Geographica I.4.2.

- Nansen 1911, p. 53; Geminus, Introduction to the Phenomena, vi.9.

- Page 54.

- The mouth was further north than it is today; even so, 48.4° is near Dnipro. The Greeks must be allowed some inaccuracy for their measurements. In any case damming has changed the river a great deal and a few thousand years has been enough to change the courses of many rivers.

- Burton 1875, p. 10.

- Geographica IV.5.5.

- Nelson points out that this passage in Strabo contains "ambiguity": he could mean either one drink made from grain and honey, in which case it would have to be mead unless one classified it as a combination of mead and beer, or two drinks, mead and beer. Strabo used the singular pōma for "beverage" but the neuter singular does not exclude a type of which there are two specifics. Some mead also is and was made with hops and is strained briefly through grain (see mead) The issue remains. See Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 0-415-31121-7.

- Translation from Chevallier 1984.

- IV.5.

- Natural History IX.71.

- Natural History XXXII.32.

- Aristotle; William Ogle (1882). On the Parts of Animals. London: Kegan, Paul, French & Co. p. 226.

On the Parts of Animals.

- Bowditch, Nathaniel (2002). The American Practical Navigator: an Epitome of Navigation (PDF) (Bicentennial ed.). National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Geographica I.4.3.

- Lehmann, Winfred P.; Helen-Jo J. Hewitt (1986). A Gothic Etymological Dictionary. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 164. ISBN 9789004081765.

- Natural History IV.27.13 or IV.13.95 in the Loeb edition.

- Gimbutas 1967, p. 22.

- Gimbutas 1967, p. 101.

- Herodotus IV.105.

- 7.2.4.

- Germania, 45.

- III.5.

- Novotná, Petra. "Glottochronology and Its Application to the Balto-Slavic Languages". Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Polybius XXXIV.5.

- Lewis, Michael Jonathan Taunton (2001). Surveying Instruments of Greece and Rome. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-79297-4.

- Geographica II.5.34: "If, then, we cut the greatest circle of the Earth into three hundred and sixty sections, each of these sections will have seven hundred stadia."

- Geographica II.5.41.

- II.1.12 and again in II.5.8.

- Nansen 1911, p. 46.

- Most students of Pytheas presume that his differences from modern calculations represent error due to primitive instrumentation. Rawlins assumes the opposite, that Pytheas observed the sun correctly, but his observatory was a few miles south of west-facing Marseille. Working backward from the discrepancy, he arrives at Maire Island or Cape Croisette, which Pytheas would have selected for better viewing over the south horizon. To date there is no archaeological or other evidence to support the presence of such an observatory; however, the deficit of antiquities does not prove non-existence. Rawlins, Dennis (December 2009). "Pytheas' Solstice Observation Locates Him" (PDF). DIO & the Journal for Hysterical Astronomy. 16: 11–17.

- Bowditch, Nathaniel (2002). The American Practical Navigator: an Epitome of Navigation (PDF) (Bicentennial ed.). National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. p. 243. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

That is, the altitude of the elevated pole is equal to the declination of the zenith, which is equal to the latitude

- The report survives in the Commentary on the Phainomena of Aratos and Eudoxos, 1.4.1, fragments of which are preserved in Hipparchos.

- Rihll, T.E. "Greek and Roman Science and Technology, V3; Specific subjects; Astronomy". Note 14: Swansea University. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Geographica II.5.3.

- Geographica II.5.7.

- Strabo's extensive presentation of the geographic model including the theory of the Arctic is to be found in Book II Chapter 5.

- Nansen 1911, p. 53.

- Nansen 1911, p. 52.

- Strabo II.1.12,13.

- However, Srabo II.1.18 implied 3800, still attributed to Hipparchus. Eratosthenes has quite a different view. See under Thule.

- Éire#Etymology

- Strabo III.2.11.

- Strabo II.1.18. The notes of the Loeb Strabo summarized and explained this information.

- Natural History Book II Chapter 99

- "Harmonic Constants". National Oceanography Centre. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012.

- "Highest & lowest predicted tides". National Oceanography Centre. 3 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012.

- Tozer, Henry Fanshawe (1897). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: Cambriddge University Press. p. 225..

- Diels, Hermann, ed. (1879). Doxographi Graeci (in Ancient Greek). Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 383. Downloadable Internet Archive. Diels includes two matching fragments of Aëtius' Placita, one from Pseudo-Plutarch Epitome Book III Chapter 17 often included in Moralia and the other from Stobaeus' Extracta Book I Chapter 38 [33].

- Lionel Pearson, review of Hans Joachim Mette, Pytheas von Massalia (Berlin: Gruyter) 1952, in Classical Philology 49.3 (July 1954), pp. 212–214.

- Markham 1893, p. 510.

- Geographica II.3.5.

- Graham, Thomas H.B. (July–December 1893). "Thule and the Tin Islands". The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. CCLXXV. p. 179.

- Sarton, Georg (1993). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. New York: Courier Dover Publications. pp. 524–525. ISBN 978-0-486-27495-9.

His fate was comparable to that of Marco Polo in later times; some of the things that they told were so extraordinary, so contrary to common experience, that wise and prudent men could not believe them and concluded they were fables

Bibliography

- Burton, Richard F. (1875). Ultima Thule; or, A Summer in Iceland. London and Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo.

Ultima Thule; or, A Summer in Iceland.

- Chevallier, R. (December 1984). "The Greco-Roman Conception of the North from Pytheas to Tacitus". Arctic. 37 (4): 341–346. doi:10.14430/arctic2217. hdl:10515/sy5tb0xz8. JSTOR 40510297.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2002). The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek: The Man Who Discovered Britain (Revised ed.). Walker & Co, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-200254-2.

- Frye, John; Harriet Frye (1985). North to Thule: an imagined narrative of the famous "lost" sea voyage of Pytheas of Massalia in the fourth century B.C. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-0-912697-20-8.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1967). Daniel, Glyn (ed.). The Balts. Ancient Peoples and Places. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

- Hawkes, C.F.C. (1977). Pytheas: Europe and the Greek Explorers. Oxford: Blackwell, Classics Department for the Board of Management of the Myres Memorial Fund. 090356307X.

- Kaplan, Philip G. (2013). "Pytheas of Massalia". In Bagnall, Roger S (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 1. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah21281.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- Markham, Clements R. (June 1893). "Pytheas, The Discoverer of Britain". The Geographical Journal. London: The Royal Geographical Society. 1 (6): 504–524. doi:10.2307/1773964. JSTOR 1773964.

- Nansen, Fridtjof (1911). In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times. Vol. I. Translated by Arthur G. Chater. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.

- Roller, Duane W. (2006). Through the Pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman Exploration of the Atlantic. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-37287-9.

- Roseman, Christina Horst (1994). Pytheas of Massalia: On the ocean: Text, translation and commentary. Ares Publishing. ISBN 0-89005-545-9.

- Smith, William (1880). "Pytheas". A dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. III. London: J. Murray.

- Spekke, Arnolds (1957) The ancient amber routes and the geographical discovery of the Eastern Baltic. Stockholm: Goppers.

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur (1940). Ultima Thule: further mysteries of the Arctic. New York: Macmillan Co.

- John Taylor, Albion: the earliest history (Dublin, 2016)

- Tozer, Henry Fanshawe (1897). History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: University Press.

History of Ancient Geography.

- Warmington, Eric Herbert; Spawforth, Antony (2015). "Pytheas, Greek navigator, c. 310–306 BCE". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5459. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

External links

| Library resources about Pytheas |

| By Pytheas |

|---|

- Bunbury, Edward Herbert; Beazley, Charles Raymond (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). pp. 703–704.

- Darbyshire, Adrian (8 April 2008). "Pytheas visited the Isle of Man in 300 BC – claim". Isle of Man Today. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Deruelle, Jean. "Pytheas, megaliths and the tides". from: L'Atlantide des Mégalithes. Editions France-Empire, 1999.

- Engels, Andre. "Pytheas". Discoverer's Web. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- "The Northern Lights Route: The Voyage of Pytheas to Thule". University Library of Tromsø. 1999. Retrieved 5 November 2008.