Quasi-star

A quasi-star (also called black hole star) is a hypothetical type of extremely massive and luminous star that may have existed early in the history of the Universe. Unlike modern stars, which are powered by nuclear fusion in their cores, a quasi-star's energy would come from material falling into a black hole at its core.[1]

Formation and properties

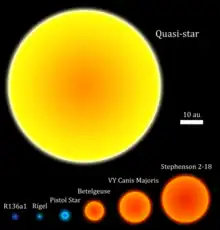

A quasi-star would have resulted from the core of a large protostar collapsing into a black hole, where the outer layers of the protostar are massive enough to absorb the resulting burst of energy without being blown away or falling into the black hole, as occurs with modern supernovae. The star would have been almost 10 million solar masses at this point.[1] Quasi-stars may have also formed from dark matter halos (up to 100 million solar masses; for reference, some small galaxies have only 5 million solar masses) drawing in enormous amounts of gas via gravity, which can produce supermassive stars with tens of thousands of solar masses.[2][3] Formation of quasi-stars could only happen early in the development of the Universe, before hydrogen and helium were contaminated by heavier elements; thus, they may have been very massive Population III stars. Such stars would dwarf VY Canis Majoris and Stephenson 2 DFK 1, both among the largest known modern stars, in size.

Once the black hole had formed at the core of the protostar, it would continue generating a large amount of radiant energy from the infall of stellar material. This constant outburst of energy would counteract the force of gravity, creating an equilibrium similar to the one that supports modern fusion-based stars.[4] Quasi-stars would have had a short maximum lifespan, approximately 7 million years,[5] during which the core black hole would have grown to about 1,000–10,000 solar masses (2×1033–2×1034 kg).[1][4] These intermediate-mass black holes have been suggested as the progenitors of modern supermassive black holes such as the one in the center of the Galaxy.

Quasi-stars are predicted to have had surface temperatures higher than 10,000 K (9,700 °C).[4] At these temperatures, and with a radius of approximately 800 thousand times that of the Sun (as large as the Solar System), each one would be about as luminous as a small galaxy.[1] As a quasi-star cools over time, its outer envelope would become transparent, until further cooling to a limiting temperature of 4,000 K (3,730 °C) and growing to a size of 30 solar systems in terms of length.[4] This limiting temperature would mark the end of the quasi-star's life since there is no hydrostatic equilibrium at or below this limiting temperature.[4] The object would then quickly dissipate, leaving behind the intermediate mass black hole.[4]

See also

- Accretion (astrophysics) – Accumulation of particles into a massive object by gravitationally attracting more matter

- Accretion disk – Structure formed by diffuse material in orbital motion around a massive central body

- Blitzar – Hypothetical type of neutron star

- Thorne–Żytkow object – Theoretical Hybrid star type

- Neutron star – Collapsed core of a massive star

References

- Battersby, Stephen (29 November 2007). "Biggest black holes may grow inside 'quasistars'". NewScientist.com news service.

- Yasemin Saplakoglu (29 September 2017). "Zeroing In on How Supermassive Black Holes Formed". Scientific American. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Mara Johnson-Goh (20 November 2017). "Cooking up supermassive black holes in the early universe". Astronomy. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Begelman, Mitch; Rossi, Elena; Armitage, Philip (2008). "Quasi-stars: accreting black holes inside massive envelopes". MNRAS. 387 (4): 1649–1659. arXiv:0711.4078. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.387.1649B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13344.x. S2CID 12044015.

- Schleicher, Dominik R. G.; Palla, Francesco; Ferrara, Andrea; Galli, Daniele; Latif, Muhammad (25 May 2013). "Massive black hole factories: Supermassive and quasi-star formation in primordial halos". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 558: A59. arXiv:1305.5923. Bibcode:2013A&A...558A..59S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321949. S2CID 119197147.

Further reading

- Ball, Warrick H.; Tout, Christopher A.; Żytkow, Anna N.; Eldridge, John J. (2011). "The structure and evolution of quasi-stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (3): 2751–2762. arXiv:1102.5098. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.2751B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18591.x. S2CID 119239346.

- Ball, Warrick H. (2012). "Quasi-stars and the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limit". arXiv:1207.5972.

- Czerny, Bozena; Janiuk, Agnieszka; Sikora, Marek; Lasota, Jean-Pierre (2012). "Quasi-Star Jets as Unidentified Gamma-Ray Sources". The Astrophysical Journal. 755 (1): L15. arXiv:1207.1560. Bibcode:2012ApJ...755L..15C. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/755/1/L15. S2CID 113397287.

- Fiacconi, Davide; Rossi, Elena M. (2017). "Light or heavy supermassive black hole seeds: The role of internal rotation in the fate of supermassive stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 464 (2): 2259–2269. arXiv:1604.03936. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2505.

- Herrington, Nicholas P.; Whalen, Daniel J.; Woods, Tyrone E. (2023). "Modelling supermassive primordial stars with <SCP>mesa</SCP>". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 521: 463–473. doi:10.1093/mnras/stad572.