Agua de la Piedra Formation

The Agua de la Piedra Formation (FAP, Spanish names include Estratos de Agua de la Piedra and Complejo Volcano-sedimentario del Terciario inferior)[1] is a Late Oligocene (Deseadan in the SALMA classification) geologic formation of the Malargüe Group that crops out in the southernmost Precordillera and northernmost Neuquén Basin in southern Mendoza Province, Argentina.[2]

| Agua de la Piedra Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Late Oligocene (Deseadan) ~ | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Malargüe Group |

| Sub-units | "Rodados Lustrosos" level |

| Underlies | alluvium |

| Overlies | Pircala-Coihueco Formation |

| Thickness | 37 metres (121 ft) (tuffs) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Tuff |

| Other | Paleosols |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 36.6°S 69.7°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 37.8°S 62.9°W |

| Region | southern Mendoza Province |

| Country | Argentina |

| Extent | southernmost Precordillera northernmost Neuquén Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named by | Gorroño et al. |

| Location | Quebrada Fiera, Malargüe |

| Year defined | 1979 |

| Coordinates | 36°33′13.3″S 69°42′3.5″W |

| Region | Mendoza Province |

| Country | Argentina |

| Thickness at type section | 37 metres (121 ft) (tuffs) |

Agua de la Piedra Formation (Argentina) | |

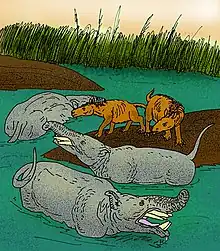

The strictly terrestrial tuffs and paleosols of the formation, geologically belonging to Patagonia, have provided a wealth of mammal fossils of various groups at Quebrada Fiera, including Mendozahippus fierensis, Pyrotherium, Coniopternium and Fieratherium. Terror birds reminiscent of the terror bird Andrewsornis and indeterminate remains of the phorusrhacid family have found in conjunction with the mammals.

Regional geology

The Agua de la Piedra is geologically part of the Neuquén Basin, Argentina's most prolific onshore petroleum producing basin of northwestern Patagonia, and crops out in the geographical feature of the Andean orogeny; the Argentinian Precordillera of the higher Andes in the hinterland. The Malargüe Group, of which the Agua de la Piedra Formation is the uppermost unit, hosts among the most spectacular dinosaur fossils and nesting sites in the Allen Formation, the lowermost stratigraphic unit of the group.

The Jagüel Formation, overlying the Allen Formation, hosts the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary and has provided fossils of marine reptiles including mosasaurs[3] and the marine turtle Euclastes meridionalis. The Roca Formation, overlying the Jagüel Formation shows evidence of Atlantic waters depositing the evaporites, claystones and limestones of the formation.[4][5]

The Neuquén Basin started forming in the latest Jurassic as one of the rift basins resulting from the break-up of Pangea. While the earlier formations in the basin are mostly distal terrestrial in nature, the Agua de la Piedra Formation is a unique combination of purely terrestrial influence (paleosols) with the early Andean volcanism in the form of tuffs.

Oligocene South America

Climate

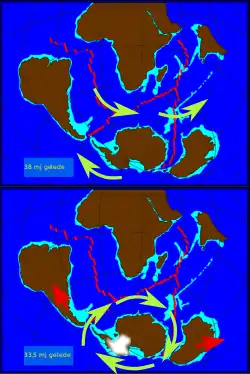

Oligocene South America differed quite substantially from the Eocene period preceding it. Isolated from Gondwana for 70 million years, the continent had developed widespread lush forests with their own specific faunas. The climate drastically cooled at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary with global cooling as a result of the formation of the Antarctic Ocean current. The South American landscape became more arid than in the Eocene with ongoing volcanism related to the Andean orogeny affecting the local climates.

Oligocene fauna

The Oligocene of South America is characterized by the arrival of the first monkeys, possibly rafting from Africa, which in the Oligocene was significantly removed from South America. The first rodents had arrived to the island continent in the Late Eocene before,[6] perhaps using similar methods of transoceanic transport. The rodents of South America diversified in the Oligocene. Cabeza Blanca, where the Sarmiento Formation outcrops, has provided the richest and most diverse Oligocene fauna of South America.[7]

The cooler Oligocene climate led to the wide-spread extension of savanna and other grassland biomes. In the Early Oligocene, these rodents inhabited open and arid landscapes with wind-blown dust and grasslands environments.[8]

Monkeys and rodents

The oldest confirmed New World monkey fossils stem from the Deseadan formations Salla in presently Andean Bolivia (the approximately 1,000 grams (2.2 lb) weighing Branisella boliviana and Szalatavus attricuspis half the size of Branisella) and the 2,000 g (4.4 lb) heavy Canaanimico from the Chambira of Amazonian Peru.[9]

The rodents had arrived in the Late Eocene and diversified greatly during the Deseadan following the appearance of Andemys with species A. frassinettii and A. termasi in the Tinguirirican (Abanico Formation; Tinguiririca fauna). Caviomorphs arrived in Patagonia during the latest Eocene or early Oligocene, and by the Late Oligocene they were highly diversified, with representatives of the four main lineages. A great morphological disparity, at least in tooth morphology, was then acquired mainly by the development of hypsodonty in several lineages. The early evolution of each of the major clades was complex, especially for chinchilloids and octodontoids. The first stages of the evolution of cavioids are more obscure because they are recognized through the relatively derived Deseadan species of Cavioidea.[10]

The Oligocene (Tinguirirican and Deseadan SALMAs plus La Cantera fauna) has a rich record of caviomorphs showing a greater morphological disparity than older faunas. Representatives of the four superfamilies, with the archetypal dental features that characterize species of the subsequent SALMAs, can be clearly recognized, at least since the Deseadan SALMA. Although a few genera (e.g., Andemys, Branisamys) cannot be assigned with certainty to any supra generic taxa. The Acaremyidae were likely a group of austral differentiation. The first representatives, the Deseadan Platypittamys brachyodon, Galileomys baios and Changquin woodi,[11] attest to its differentiation into several lineages.[12]

Oligocene volcanism

Early Andean volcanism in the Southern Cone of South America dating to the Oligocene has been found in:

Description

The formation comprises the "Rodados Lustrosos" level, formed by clastic heterogeneous conglomerates in a silty matrix, considered as the stratigraphic evidence of the Pehuenche orogenic phase of the Andean orogeny, followed by uniform sequences, variable in thickness, of whitish-ocher tuffaceous paleosols with concretions and whitish-gray tuffs with intercalations of pyroclastic deposits.[19]

The upper part of the Agua de la Piedra Formation consists of 37 metres (121 ft) of white-grayish tuffs and tobaceous paleosols, with laminated or massive parallel stratification constitute the fossiliferous level of Quebrada Fiera.[20] The formation overlies the Pircala-Coihueco Formation.[21]

Depositional environment

The studied profiles of the Agua de la Piedra Formation show large lateral lithological varieties, typical of alluvial fan depositional setings. The climate during deposition has been estimated to be semi-arid and the differential thicknesses of facies associations within the Agua de la Piedra Formation may represent the infill of minibasins in the forming foreland of the Andes. Sedimentary loading can enhance the effect of tectonic forces in foreland basins. The variety in volcanic fragments and composition indicates local ash fall caused by contemporaneous volcanism in the area of deposition.[22]

2017 research on the Deseadan fauna (late Oligocene) from Quebrada Fiera, south of Mendoza Province, Argentina, evidences a rich mammal assemblage that shows the existence of common elements with Deseadan faunal associations of Patagonia and those of lower latitudes such as Salla, Bolivia, as well as endemic taxa of different groups.[23]

Endemism refers to Notohippidae (Mendozahippus fierensis), Leontiniidae (Gualta cuyana), Homalodotheriidae (Asmodeus petrasnerus) and Metatheria (Fieratherium sorex); to these mammals a new terrestrial snail has been added in 2016.[24]

Faunal data published in 2019 confirm the Deseadan age, but as per 2020, absolute dating is lacking for Quebrada Fiera.[19]

Paleontological significance

Quebrada Fiera

The Quebrada Fiera site is situated in the Malargüe Department,[25] southern Mendoza Province, Argentina, in the foothills of the Andes Range. The fossiliferous levels are located at around 36°33′13.3″S 69°42′3.5″W at 1,300 to 1,406 metres (4,265 to 4,613 ft) elevation. The site was discovered during a geological prospection carried out by Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) in the late 1970s (Gorroño et al., 1979). Later on, other fossil bearing levels were found at the southern side of the ravine,[26] located at around 36°33′26″S 69°41′35″W, 1,316 metres (4,318 ft) elevation.[19]

The site is one of five recognized fossiliferous sites in Mendoza Province, with Divisadero Largo, where the Santacrucian Mariño Formarion is found, Huaquerías, defining the Huayquerian in the Huayquerías Formation, the Aisol Formation of central Mendoza and the Uspallata Group and Carrizal Formations in the north of the province.[21]

The geological characterization and the preliminary faunal list were published by Gorroño et al. (1979). The faunal assemblage was then assigned to the Late Oligocene (Deseadan SALMA) based on the presence of two typical representatives of the Deseadean fauna of Patagonia; Pyrotherium Ameghino 1888 and Proborhyaena gigantea Ameghino 1897,[19] both also found in the Puesto Almendra member of the Sarmiento Formation.[27]

The species epithet Mendozahippus fierensis and genus Fieratherium refer to Quebrada Fiera.[25][26][28][29][30]

Fossil content

The formation has provided fossils of:[2]

| Group | Clade | Taxa | Site | Images | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ungulates | Macraucheniidae | Coniopternium andinum | Quebrada Fiera North |  | |

| Proterotheriidae | cf. Lambdaconus suinus | Quebrada Fiera North |  | ||

| Pyrotheriidae | Pyrotherium romeroi | Quebrada Fiera North |  | ||

| Pyrotherium sp. | Quebrada Fiera South | ||||

| Litopterna | Litopterna indet. | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Cingulata | Dasypodidae | Meteutatus aff. lagenaformis | Quebrada Fiera North | ||

| ?Prozaedyus aff. impressus | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Stenotatus aff. ornatus | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Xenarthra | Glyptodontinae | Glyptodontinae indet. | Quebrada Fiera North |  | |

| Megalonychidae | ?Megalonychidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

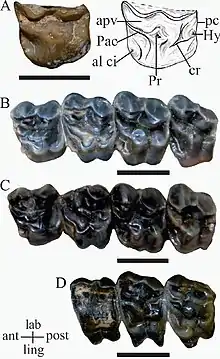

| Notoungulata | Notohippidae | Mendozahippus fierensis | Quebrada Fiera South | ||

| Quebrada Fiera North | |||||

| Notohippidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera North |  | |||

| Archaeohyracidae | cf. Archaeotypotherium sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Archaeohyrax suniensis | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Hegetotheriidae | Prosotherium garzoni | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| cf. Prosotherium sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Prohegetotherium malalhuense | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| P. schiaffinoi | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| P. cf. sculptum | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Prohegetotherium sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Hegetotheriopsis sulcatus | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Homalodotheriidae | Asmodeus petrasnerus | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Interatheriidae | Argyrohyrax proavus | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Progaleopithecus sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Interatheriidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera South | ||||

| Leontiniidae | Gualta cuyana | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Mesotheriidae | Trachytherus cf. spegazzinianus | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Toxodontidae | Proadinotherium sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Toxodontidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||||

| Rodents | Acaremyidae | Acaremyidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||

| Sparassodonta | Borhyaenidae | Pharsophorus sp. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||

| Proborhyaenidae | Proborhyaena gigantea | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Theriiformes | Fieratherium sorex | Quebrada Fiera North | |||

| Birds | Phorusrhacidae | cf. Andrewsornis sp. | Quebrada Fiera North |  | |

| Phorusrhacidae indet. | Quebrada Fiera South |  | |||

| Invertebrates | Gastropods | Gastropoda indet. | Quebrada Fiera North | ||

SALMA correlations

The Deseadan South American land mammal age (SALMA) is equivalent to the Arikareean in the North American land mammal age (NALMA) and the Harrisonian in the 2000 version of the classification. It overlaps with the Hsandagolian of Asia and the MP 25 zone of Europe, the Waitakian and the Landon epoch of New Zealand.

| Formation | Rancahué | Guillermo | Mariño | Deseado | Sarmiento | Salla | Lacayani | Fray Bentos | Moquegua | Chambira | Barzalosa | Tremembé | Cascadas | Map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | Neuquén | Austral | Cuyo | Deseado | San Jorge | Salla | Subandean | Norte | Moquegua | Ucayali | VSM | Taubaté | Panama |  Agua de la Piedra Formation (South America) | |

| Country | |||||||||||||||

| Archaeohyrax | |||||||||||||||

| Prohegetotherium | |||||||||||||||

| Pyrotherium | |||||||||||||||

| Pharsophorus | |||||||||||||||

| Trachytherus | |||||||||||||||

| Proadinotherium | |||||||||||||||

| Proborhyaena | |||||||||||||||

| Meteutatus | |||||||||||||||

| Andrewsornis | |||||||||||||||

| Terror birds | |||||||||||||||

| Rodents | |||||||||||||||

| Reptiles | |||||||||||||||

| Primates | |||||||||||||||

| Flora | |||||||||||||||

| Insects | |||||||||||||||

| Environments | Alluvial | Fluvial | Eolian Alluvial-fluvial | Fluvial | Alluvial | Fluvial-alluvial | Fluvial | Fluvio-lacustrine | Alluvial-fluvial | Lacustrine | Fluvial | ||||

| Volcanic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

See also

References

- Combina et al., 1994, p.418

- Agua de la Piedra Formation in the Paleobiology Database

- Hoja 3969-II Neuqúen, 2007

- Archuby et al., 2016

- Malamuián & Náñez, 2011

- Vassallo & Antenucci, 2015, p.6

- Vucetich et al., 2015, p.21

- Ojeda et al., 2015, p.123

- Silvestro et al., 2017, p.14

- Vucetich et al., 2015, p.11

- Vucetich et al., 2014, p.692

- Vucetich et al., 2015, p.18

- Elgueta et al., 2000

- Alfaro & Gantz, 1997

- Villablanca et al., 2003

- Mella & Quiroz, 2010

- García et al., 1999

- Zeilinger et al., 2015

- Schmidt et al., 2019, p.370

- Cerdeño, 2012, p.378

- Cerdeño, 2012, p.376

- Combina et al., 1994, p.420

- Hernández Pino et al., 2017, p.195

- Miquel & Cerdeño, 2016

- Quebrada Fiera at Fossilworks.org

- Quebrada Fiera South in the Paleobiology Database

- Gran Blanca in the Paleobiology Database

- Cerdeño & Reguero, 2015

- Seoane & Cerdeño, 2014

- Cerdeño & Vera, 2014a

- Schmidt et al., 2019, p.371

- Schmidt et al., 2019, p.375

- Cerdeño & Vera, 2017

- Carlini et al., 2009

- Cerdeño & Vera, 2010

- Cerdeño & Vera, 2014b

- Cerdeño et al., 2010

- Vera et al., 2017

- Seoane et al., 2019

- Kramarz & Bond, 2017

- Hernández Pino et al., 2017, p.206

- Hernández Pino et al., 2017, p.201

- Cerdeño, 2014

- Hernández Pino et al., 2017, p.198

- Hernández Pino et al., 2017, p.200

- Forasiepi et al., 2014

Bibliography

- General

- Woodburne, M.O.; F.J. Goin; M. Bond; A.A. Carlini; J.N. Gelfo; G.M. López; A. Iglesias, and A.N. Zimicz. 2013. Paleogene Land Mammal Faunas of South America; a Response to Global Climatic Changes and Indigenous Floral Diversity. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 21. 1–73. Accessed 2019-02-15.

- Johnson, K. G.; M. R. Sánchez Villagra, and O. A. Aguilera. 2009. The Oligocene-Miocene Transition on Coral Reefs in the Falcon Basin (NM Venezuela). PALAIOS 24. 59–69. .

- Regional geology

- Balgord, Elizabeth A. 2017. Triassic to Neogene evolution of the south-central Andean arc determined by detrital zircon U-Pb and Hf analysis of Neuquén Basin strata, central Argentina (34°S–40°S). Lithosphere 9. 453–462. .

- Archuby, Fernando; Leonardo Salgado; Soledad Brezina, and Ana Parras. 2016. Dos orillas, dos mundos: Paleontología del Alto Valle del río Negro. El Ojo del Cóndor 7. 10–15. .

- Bellosi, Eduardo S., and J. Marcelo Krause. 2014. Onset of the Middle Eocene global cooling and expansion of open-vegetation habitats in central Patagonia. Andean Geology 41. 29–48. Accessed 2019-03-04.

- Combina, Ana María, and Francisco Nullo. 2011. Ciclos tectónicos, volcánicos y sedimentarios del Cenozoico del sur de Mendoza-Argentina (35-37° S y 69° 30'W). Andean Geology 38. 198–218. Accessed 2018-09-11.

- Malumián, Norberto, and Carolina Náñez. 2011. The Late Cretaceous–Cenozoic transgressions in Patagonia and the Fuegian Andes: foraminifera, palaeoecology, and palaeogeography. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 103(2). 269–288. . doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01649.x

- Rodríguez, María F.; Héctor A. Leanza, and Matías Salvarredy Aranguren. 2007. Hoja Geológica 3969-II - Neuquén, 32–35. Servicio Geológico Minero Argentino - Instituto de Geología y Recursos Minerales.. ISSN 0328-2333

- Ramos, Víctor A., and Suzanne Mahlburg Kay. 2006. Evolution of an Andean Margin: A Tectonic and Magmatic View from the Andes to the Neuquén Basin (35–39°S lat). Special Paper of the Geological Society of America 407. 1–17. Accessed 2018-09-06.

- Combina, Ana María; Francisco Nullo; G. Stephens, and Paul Baldauf. 1994. Paleoambientes de la Formación Agua de la Piedra, Mendoza, Argentina, 418–424. 7° Congreo geológico Chileno. Accessed 2020-08-12.

- Oligocene volcanism

- Mella, M., and D. Quiroz. 2010. Geología del Área Temuco-Nueva Imperial escala 1:100.000, Región de La Araucanía. Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería, Carta Geológica de Chile, Serie Geología Básica, 1–46. 122;

- Litvak, Vanesa D. 2009. El volcanismo oligoceno superior-mioceno inferior del grupo Doña Ana en la alta cordillera de San Juan. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 64. 201–213. .

- Zeilinger, Gerold; Fritz Schlunegger, and Guy Simpson. 2005. The Oxaya anticline (northern Chile): a buckle enhanced by river incision?. Terra Nova 17. 368–375. .

- Villablanca, D.; G. Alfaro, and L.A. Quinzio. 2003. Sedimentología de la cuenca carbonífera Neógena de Pupunahue-Mulpún, X Región de Los Lagos, Chile, 1. Departamento de Geociencias, Universidad de Concepción, 10° Congreso Geológico Chileno..

- Elgueta, Sara; Jacobus Le Roux; Paul Duhart; Michael McDonough, and Esteban Urqueta. 2000. Estratigrafía y sedimentología de la cuencas terciarias de la Región de Los Lagos (39-41°30’S), 15. Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería. ISSN 0020-3939

- García, Marcelo; Gérard Herail, and Reynaldo Charrier. 1999. Age and structure of the Oxaya Anticline: A major feature of the Miocene compressive structures of northernmost Chile, 249–252. Fourth ISAG..

- Alfaro, G., and E. Gantz. 1997. La Nueva Mina de Carbón Mulpún, Valdivia, Chile, 832–836. II; Universidad Católica del Norte, XVIII Congreso Geológico Chileno..

- Alfaro, G.; E. Gantz, and O. Magna. 1990. El yacimiento de carbón Catamutún (La Unión), 11–28. Segundo Simposio sobre el Terciario de Chile, Departamento de Geociencias, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Concepción.

- Paleontology

- Schmidt, Gabriela I.; Esperanza Cerdeño, and Santiago Hernández del Pino. 2019. Macraucheniidae and Proterotheriidae (Mammalia, Litopterna) from Quebrada Fiera (Late Oligocene), Mendoza Province, Argentina. Andean Geology 46. 368–382. Accessed 2020-08-11.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License. - Seoane, F. D.; E. Cerdeño, and H. Singleton. 2019. Re-assessment of the Oligocene genera Prosotherium and Propachyrucos (Hegetotheriidae, Notoungulata). Comptes Rendus Palevol 18. 643–662. .

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and Bárbara Vera. 2017. New anatomical data on Pyrotherium (Pyrotheriidae) from the late Oligocene of Mendoza, Argentina. Ameghiniana 54. 290–306. .

- Vera, B.; E. Cerdeño, and M. Reguero. 2017. The Interatheriinae from the Late Oligocene of Mendoza (Argentina), with comments on some Deseadan Interatheriidae. Historical Biology 29. 607–626. .

- Hernández Del Pino, Santiago; Federico D. Seoane, and Esperanza Cerdeño. 2017. New postcranial remains of large toxodontian notoungulates from the late Oligocene of Mendoza, Argentina and their systematic implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62. 195–210. Accessed 2019-02-12.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Kramarz, A. G., and M. Bond. 2017. Systematics and stratigraphical range of the hegetotheriids Hegetotheriopsis sulcatus and Prohegetotherium sculptum (Mammalia: Notoungulata). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 15. 1027–1036. .

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and Marcelo Reguero. 2015. The Hegetotheriidae (Mammalia, Notoungulata) assemblage from the late Oligocene of Mendoza, central-western Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35(2). e907173. Accessed 2015-02-13.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and Bárbara Vera. 2014a. A new Leontiniidae (Notoungulata) from the Late Oligocene beds of Mendoza Province, Argentina. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 13(11). 943–962. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and Bárbara Vera. 2014b. New data on diversity of Notohippidae from the Oligocene of Mendoza, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34. 941–950. .

- Cerdeño, Esperanza. 2014. First Record of Mesotheriidae in the Late Oligocene of Mendoza Province, Argentina. Ameghiniana 51. 366–370. .

- Forasiepi, A. M.; F. J. Goin; M. A. Abello, and E. Cerdeño. 2014. A unique, Late Oligocene shrew-like marsupial from western Argentina and the evolution of dental morphology. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 12. 549–564. .

- Seoane, Federico, and Esperanza Cerdeño. 2014. First extra-Patagonian record of Asmodeus Ameghino (Notoungulata, Homalodotheriidae) in the Late Oligocene of Mendoza Province, Argentina. Ameghiniana 51(5). 373–384. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza. 2012. Quebrada Fiera (Mendoza), an important paleobiogeographic center in the South American late Oligocene. Estudios Geológicos 67. 375–384. Accessed 2020-08-11.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and Bárbara Vera. 2010. Mendozahippus fierensis, gen. et sp. nov., new Notohippidae (Notoungulata) from the late Oligocene of Mendoza (Argentina). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(6). 1805–1817. . doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.520781

- Cerdeño, Esperanza; M. Reguero, and B. Vera. 2010. Deseadan Archaeohyracidae (Notoungulata) from Quebrada Fiera (Mendoza, Argentina) in the Paleobiogeographic Context of the South American Late Oligocene. Journal of Paleontology 84. 1177-1187. .

- Carlini, A.A.; M.R. Ciancio; J. J. Flynn; G. J. Scillato Yané, and A. R. Wyss. 2009. The phylogenetic and biostratigraphic significance of new armadillos (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Dasypodidae, Euphractinae) from the Tinguirirican (early Oligocene) of Chile. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 7. 489–503. .

- Patterson, Bryan, and Larry G. Marshall. 1978. The Deseadan, Early Oligocene, Marsupialia South America. Fieldiana: Geology 41(2). 37–100. .

- New World monkeys

- Croft, Darin A. 2016. Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys: The Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America, 1–320. Indiana University Press ISBN 9780253020949. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Fleagle, John G., and Alfred L. Rosenberger. 2013. The Platyrrhine Fossil Record, 1–256. Elsevier ISBN 9781483267074. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Hartwig, W.C., and D.J. Meldrum. 2002. The Primate Fossil Record - Miocene platyrrhines of the northern Neotropics, 175–188. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08141-2. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Terror birds

- Sedor, Fernando A.; Eliseu Vieira Dias; Renata Floriano Da Cunha, and Herculano Alvarenga. 2014. Paleogene phorusrhacid bird (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the Guabirotuba Formation, Curitiba Basin, Paraná, South of Brazil, 807. 4th International Palaeontological Congress. Accessed 2019-03-04.

- Tambussi, C.P.; R. de Mendoza; F.J. Degrange, and M.B. Picasso. 2013. Flexibility along the Neck of the Neogene Terror Bird Andalgalornis steulleti (Aves Phorusrhacidae). PLoS ONE 7(5). e37701. . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037701 PMID 22662194 PMC 3360764

- Cenizo, Marcos M. 2012. Review Of The Putative Phorusrhacidae From The Cretaceous And Paleogene Of Antarctica: New Records Of Ratites And Pelagornithid Birds. Polish Polar Research 33(3). 239–258. . doi:10.2478/v10183-012-0014-3

- Alvarenga, H.; W. Jones, and A. Rinderknecht. 2010. The youngest record of phorusrhacid birds (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the late Pleistocene of Uruguay. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 256(2). 229–234. . doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0052

- Wroe, Stephen et al. 2010. Mechanical Analysis Of Feeding Behavior In The Extinct "Terror Bird' Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae). PLoS ONE 5(8). 1–7. . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011856 PMID 20805872 PMC 2923598

- Alvarenga, Herculano M.F., and Elizabeth Höfling. 2003. Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 43(4). 55–91. . doi:10.1590/S0031-10492003000400001

- South American rodents

- Boivin, Myriam; Laurent Marivaux; Maëva J. Orliac; François Pujos; Rodolfo Salas Gismondi; Julia V. Tejada Lara, and Pierre-Olivier Antoine. 2017. Late middle Eocene caviomorph rodents from Contamana, Peruvian Amazonia. Palaeontologia Electronica 20(1). Article number 20.1.19A. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Vassallo, Aldo I., and Daniel Antenucci. 2015. Biology of Caviomorph Rodents: Diversity and Evolution, 1–330. SAREM. ISBN 9789879849736

- Vassallo, Aldo I., and Daniel Antenucci. 2015. Caviomorph rodents: an introduction. SAREM Series A Prologue. 2–10. .

- Vucetich, María G.; Michelle Arnal; Cecilia M. Deschamps; Maria E. Pérez, and Emma C. Vieytes. 2015. A brief history of caviomorph rodents as told by the fossil record. SAREM Series A Chapter 1. 11–63. .

- Ojeda, Ricardo A.; Agustina Novillo, and Agustina A. Ojeda. 2015. Large-scale richness patterns, biogeography and ecological diversification in caviomorph rodents. SAREM Series A Chapter 3. 121–138. .

- Bertrand, Ornella C.; John J. Flynn; Darin A. Croft, and André R. Wyss. 2012. Two new taxa (Caviomorpha, Rodentia) from the early Oligocene Tinguiririca fauna (Chile). American Museum Novitates 3750. 1–36. Accessed 2019-02-15.

- Antoine, P.O.; L. Marivaux; D.A. Croft; G. Billet; M. Ganerod; C. Jaramillo; T. Martin; M. Orliac, and J. Tejada, A. J. Altamirano, F. Duranthon, G. Fanjat, S. Rousse and R. Salas Gismondi. 2011. Middle Eocene rodents from Peruvian Amazonia reveal the pattern and timing of caviomorph origins and biogeography. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 279. 1319–1326. Accessed 2019-02-14.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza, and M. Guiomar Vucetich. 2007. The first rodent from the Mariño Formation (Miocene) at Divisadero Largo (Mendoza, Argentina) and its biochronological implications. Andean Geology 34. 199–207. Accessed 2017-10-23.

Regional correlations

- Mariño Formation

- Cerdeño, Esperanza; Bárbara Vera, and Ana María Combina. 2018. A new early Miocene Mesotheriidae (Notoungulata) from the Mariño Formation (Argentina): Taxonomic and biostratigraphic implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 88. 118–131. Accessed 2019-02-11.

- Rancahué Formation

- Vera, E.I. 2010. Oligocene ferns from the Rancahué Formation (Aluminé, Neuquén, Argentina): Cuyenopteris patagoniensis nov. gen., nov. sp. (Polypodiales: Blechnaceae/Dryopteridaceae) and Alsophilocaulis calveloi Menéndez emend. Vera (Cyatheales: Cyatheaceae). Geobios 43. 465–478. .

- Menéndez, C.A. 1961. Estípite petrificado de una nueva Cyatheaceae del Terciario de Neuquén. Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina de Botánica IX. 331–358. .

- Río Guillermo Formation

- Vento, B.; M. A. Gandolfo; K. C. Nixon, and M. Prámparo. 2017. Paleofloristic assemblage from the Paleogene Río Guillermo Formation, Argentina: preliminary results of phylogenetic relationships of Nothofagus in South America. Historical Biology 29. 93–107. .

- Deseado Formation

- Agnolin, Federico. 2006. Posición sistemática de algunas aves fororracoideas (Ralliformes: Cariamae) Argentinas. Revista del Museo de Ciencias Naturales 8. 27–33. Accessed 2018-09-10.

- Forasiepi, Analía M.; M. Judith Babot, and Natalia Zimicz. 2014. Australohyaena antiqua (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta), a large predator from the Late Oligocene of Patagonia. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 13(6). 503–525. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Sarmiento Formation

- Acosta Hospitaleche, Carolina, and Claudia Tambussi. 2005. Phorusrhacidae Psilopterinae (Aves) en la Formación Sarmiento de la localidad de Gran Hondonada (Eoceno Superior), Patagonia, Argentina [Phorusrhacidae Psilopterinae (Birds) in the Sarmiento Formation from the Gran Hondonada locality (Upper Eocene), Patagonia, Argentina]. Revista Española de Paleontología 20. 127–132. Accessed 2018-09-10.

- Arnal, Michelle; Alejandro G. Kramarz; M. Guiomar Vucetich, and E. Carolina Vieytes. 2014. A new early Miocene octodontoid rodent (Hystricognathi, Caviomorpha) from Patagonia (Argentina) and a reassessment of the early evolution of Octodontoidea. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34(2). 397–406. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Cheme Arriaga, Lucas; María Teresa Dozo, and Javier N. Gelfo. 2016. A new Cramaucheniinae (Litopterna, Macraucheniidae) from the early Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(6). e1229672. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Dozo, María Teresa; Martín Ciancio; Pablo Bouza, and Gastón Martínez. 2014. Nueva asociación de mamíferos del Paleógeno en el este de la Patagonia (provincia de Chubut, Argentina): implicancias biocronológicas y paleobiogeográficas. Andean Geology 41. 224–247. Accessed 2017-08-15.

- Pérez, María Encarnación; Marcelo Krause, and María Guiomar Vucetich. 2012. A new species of Chubutomys (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the late Oligocene of Patagonia and its implications on the early evolutionary history of Cavioidea sensu stricto. Geobios 45(6). 573–580. Accessed 2019-02-15.

- Shockey, Bruce J.; John J. Flynn; Darin A. Croft; Phillip Gans, and André R. Wyss. 2012. New leontiniid Notoungulata (Mammalia) from Chile and Argentina : comparative anatomy, character analysis, and phylogenetic hypotheses. American Museum Novitates 3737. 1–64. Accessed 2019-02-15.

- Sterli, Juliana; Marcelo S. De la Fuente, and J. Marcelo Krause. 2015. A new turtle from the Palaeogene of Patagonia (Argentina) sheds new light on the diversity and evolution of the bizarre clade of horned turtles (Meiolaniidae, Testudinata). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 174(3). 519–548. Accessed 2019-02-13.

- Vucetich, M.G.; M.T. Dozo; M. Arnal, and M.E. Pérez. 2015. New rodents (Mammalia) from the late Oligocene of Cabeza Blanca (Chubut) and the first rodent radiation in Patagonia. Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology 27(2). 236–257. Accessed 2019-02-13.

- Vucetich, María G.; María E. Pérez; Martín R. Ciancio; Alfredo A. Carlini; Richard H. Madden, and Matthew J. Kohn. 2014. A new acaremyid rodent (Caviomorpha, Octodontoidea) from Scarritt Pocket, Deseadan (late Oligocene) of Patagonia (Argentina). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34(3). 689–698. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Wyss, André R.; John J. Flynn, and Darin A. Croft. 2018. New Paleogene notohippids and leontiniids (Toxodontia; Notoungulata; Mammalia) from the Early Oligocene Tinguiririca Fauna of the Andean Main Range, central Chile. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 3903. 1–42. Accessed 2019-02-11.

- Salla Formation

- Reguero, Marcelo A., and Esperanza Cerdeño. 2005. New late Oligocene Hegetotheriidae (Mammalia, Notoungulata) from Salla, Bolivia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25. 674–684. Accessed 2018-09-11.

- Rincón, Ascanio D.; Bruce J. Shockey; Federico Anaya, and Andrés Solórzano. 2015. Palaeothentid Marsupials of the Salla Beds of Bolivia (Late Oligocene): Two New Species and Insights into the Post-Eocene Radiation of Palaeothentoids. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 22(4). 455–471. Accessed 2019-02-13.

- Shockey, Bruce J. 2017. New early diverging cingulate (Xenarthra: Peltephilidae) from the Late Oligocene of Bolivia and considerations regarding the origin of crown Xenarthra. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 58(2). 371–396. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Lacayani fauna

- Billet, Guillaume; Christian De Muizon, and Bernardino Mamani Quispe. 2008. Late Oligocene mesotheriids (Mammalia, Notoungulata) from Salla and Lacayani (Bolivia): implications for basal mesotheriid phylogeny and distribution. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 152. 153–200. Accessed 2018-09-11.

- Fray Bentos Formation

- Bond, Mariano; Guillermo López; Marcelo A. Reguero; Gustavo J. Scillato Yané, and María G. Vucetich. 1998. Los mamíferos de la Formación Fray Bentos (Edad mamífero Deseadense, Oligoceno Superior) de las provincias de Corrientes y Entre Ríos, Argentina. Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. Publicación Especial 5. 41–50. Accessed 2018-09-12.

- Tófalo, Ofelia Rita, and Héctor J.M. Morrás. 2009. Evidencias paleoclimáticas en duricostras, paleosuelos y sedimentitas silicoclásticas, del Cenozoico de Uruguay. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 674–686. Accessed 2018-09-12.

- Moquegua Formation

- Alván, Aldo; Katerin Ramírez; Hilmar von Eynatten; István Dunkl; Javier Jacay, and Gabriela Bertone. 2017. Evolución Geológica de las Cuencas de Antearco del Sur de Perú (Moquegua y Camaná-Mollendo): Proveniencia Sedimentaria y Análisis de Facies en Rocas Cenozoicas. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica del Perú 112. 53–77. Accessed 2018-09-10.

- Shockey, Bruce J.; Guillaume Billet, and Rodolfo Salas Gismondi. 2016. A new species of Trachytherus (Notoungulata: Mesotheriidae) from the late Oligocene (Deseadan) of Southern Peru and the middle latitude diversification of early diverging mesotheriids. Zootaxa 4111(5). 565–583. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Chambira Formation

- Boivin, Myriam; Laurent Marivaux, and Pierre-Olivier Antoine. 2019. New insight from the Paleogene record of Amazonia into the early diversification of Caviomorpha (Hystricognathi, Rodentia): phylogenetic, macroevolutionary, and paleobiogeographic implications. Geodiversitas 41(4). 143–245. Accessed 2019-02-28.

- Boivin, Myriam; Laurent Marivaux; Adriana M. Candela; Maëva J. Orliac; François Pujos; Rodolfo Salas Gismondi; Julia V. Tejada Lara, and Pierre-Olivier Antoine. 2016. Late Oligocene caviomorph rodents from Contamana, Peruvian Amazonia. Papers in Palaeontology 3(1). 69–109. Accessed 2019-02-12.

- Marivaux, Laurent; Sylvain Adnet; Ali J. Altamirano Sierra; Myriam Boivin; François Pujos; Anusha Ramdarshan; Rodolfo Salas Gismondi; Julia Tejada, and Pierre-Olivier Antoine. 2016. Neotropics provide insights into the emergence of New World monkeys: New dental evidence from the late Oligocene of Peruvian Amazonia. Journal of Human Evolution 97. 159–175. Accessed 2019-02-04.

- Barzalosa Formation

- Acosta, Jorge E.; Rafael Guatame; Juan Carlos Caicedo A., and Jorge Ignacio Cárdenas. 2002. Mapa Geológico de Colombia - Plancha 245 - Girardot - 1:100,000 - Memoria Explicativa, 1–92. INGEOMINAS.

- Acosta, Jorge E., and Carlos E. Ulloa. 2001. Mapa Geológico de Colombia - Plancha 246 - Fusagasugá - 1:100,000 - Memoria Explicativa, 1–77. INGEOMINAS.

- Tremembé Formation

- Do Couto Ribeiro, Graziella. 2010. Avaliação morfológica, taxonômica e cronológica dos mamíferos fósseis da Formação Tremembé (Bacia de Taubaté), Estado de São Paulo, Brasil, 1–112. Universidade de São Paulo.

- Malabarba, Maria Claudia, and John G. Lundberg. 2007. A fossil loricariid catfish (Siluriformes: Loricarioidea) from the Taubaté Basin, eastern Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology 5. 263–270. Accessed 2018-10-08.

- Olson, Storrs L., and Herculano M.F. Alvarenga. 2002. A new genus of small teratorn from the Middle Tertiary of the Taubate Basin, Brazil (Aves: Teratornithidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 115. 701–705. Accessed 2017-09-04.

- Las Cascadas Formation

- Rincón, A. F.; J. I. Bloch; C. Suárez; B. J. MacFadden, and C. A. Jaramillo. 2012. New floridatragulines (Mammalia, Camelidae) from the early Miocene Las Cascadas Formation, Panama. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32. 456–475. .

Further reading

- Encinas, Alfonso; Folguera, Andrés; Bechis, Florencia; Finger, Kenneth L.; Zambrano, Patricio; Pérez, Felipe; Benarbé, Pablo; Tapia, Francisca; Riffo, Ricardo; Buatois, Luis; Orts, Darío; Nielsen, Sven N.; Valencia, Victor V.; Cituño, José; Oliveros, Verónica; De Girolamo Del Mauro, Lizet; Ramos, Víctor A. (2018). "The Late Oligocene–Early Miocene Marine Transgression of Patagonia". In Folguera, A.; Contreras Reyes, E.; Heredia, N.; et al. (eds.). The Evolution of the Chilean-Argentinean Andes. Springer. pp. 443–474. ISBN 978-3-319-67774-3.

- Woodburne, M.O. 2010. The Great American Biotic Interchange: Dispersals, Tectonics, Climate, Sea Level and Holding Pens. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 17(4). 245–264. . doi:10.1007/s10914-010-9144-8 PMID 21125025 PMC 2987556

- Webb, S. David. 2006. The Great American Biotic Interchange: Patterns and Processes. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 93(2). 245–257. . doi:10.3417/0026-6493(2006)93[245:TGABIP2.0.CO;2]