Itaboraí Formation

The Itaboraí Formation (Portuguese: Formação Itaboraí)[1] is a highly fossiliferous geologic formation and Lagerstätte[2] of the Itaboraí Basin in Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil. The formation reaching a thickness of 100 metres (330 ft) is the defining unit for the Itaboraian South American land mammal age (SALMA), dating to the Early Eocene, approximately 53 to 50 Ma.

| Itaboraí Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Early Eocene (Itaboraian) ~ | |

| |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Sub-units | See text |

| Underlies | Early Eocene basalt & Late Eocene to Early Oligocene conglomerates (Rio Frio Formation) |

| Overlies | Precambrian basement |

| Area | 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi) |

| Thickness | up to 100 m (330 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Limestone, marl |

| Other | Travertine, lignite |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 22.1°S 41.6°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 25.0°S 30.0°W |

| Region | Rio de Janeiro |

| Country | |

| Extent | Itaboraí Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Itaboraí |

| Named by | Leinz |

| Year defined | 1938 |

Itaboraí Formation (Brazil) | |

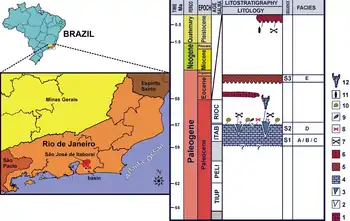

The formation is restricted to the Itaboraí Basin, a minibasin of 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi) around the city of Itaboraí, 34 kilometres (21 mi) northeast of Rio de Janeiro, and comprises limestones, marls and lignites, deposited in an alluvial to lacustrine environment, dominated by heavy rainfall. The formation overlies Precambrian basement and is overlain by Early Eocene basalts and Late Eocene to Early Oligocene conglomerates.

The up to 100 metres (330 ft) thick formation has provided many fossil mammals of various groups among which the marsupials and related metatherians dominate, birds, snakes, crocodiles, amphibians, and several species of gastropods. Several genera and species were named after the formation; the marsupials Itaboraidelphys camposi and Carolopaulacoutoia itaboraiensis, the birds Itaboravis elaphrocnemoides, Eutreptodactylus itaboraiensis and Eutreptodactylus itaboraiensis, the snake Itaboraiophis depressus and the caiman Eocaiman itaboraiensis and the gastropods Itaborahia lamegoi, Biomphalaria itaboraiensis and Gastrocopta itaboraiensis.

The formation is the richest Cenozoic fossiliferous formation of Brazil, leading to the establishment of the Parque Paleontológico de São José de Itaboraí ("São José de Itaboraí Paleontological Park") in 1995. The site is a candidate for becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Etymology

The word "Itaboraí" is of Tupi origin, and has two possible etymologies:

Description

The Itaboraí Formation is restricted to the Itaboraí Basin, a minibasin stretching across an area of 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi) of 1,400 by 500 metres (4,600 ft × 1,600 ft), in the vicinity of Itaboraí 34 kilometres (21 mi) northeast of Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil.[5] Between 1933 and 1984, a local cement company exploited the rocks in the area and their workers discovered the first fossil remains in the formation.[6] The now abandoned and largely inaccessible limestone quarries of this locality have yielded a diverse mammalian fauna from early late Paleocene fissure fillings.[7] The sediments of the formation were described by Leinz in 1938.[8] Presently, the basin is filled up with water impeding any collecting activity.[9]

Basin history

The small basin, a small half-graben, is the oldest[10] and smallest[11] of several Cenozoic rift basins stretching across 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) along a west-southwest to east-northeast trend between the Paraná Basin to the northwest and the Santos Basin to the southeast, separated by the Serra da Mantiqueira and Serra do Mar respectively. This Continental Rift of Southern Brazil (CRSB) comprises the Curitiba, São Paulo, Taubaté, Resende, Volta Redonda, Macacu, Barra de São João and Itaboraí Basins.[12]

An erosional surface, correlated with a 55 Ma sea-level lowstand representing the Paleocene-Eocene transition and associated with magmatism, has been recorded in the various Atlantic marginal basins along the Brazilian coast; Pelotas, Santos, Campos, Espírito Santo, Cumuruxatiba, Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Basins.[13]

Stratigraphy

The Itaboraí Formation rests unconformably on top of the Precambrian Paraíba do Sul Group, part of the Meso- to Neoproterozoic Paraíba do Sul Complex.[14] The Paleogene succession of the minibasin reaches a thickness of 100 metres (330 ft) and consists of three depositional sequences, with the Itaboraí Formation representing the first two;[15]

- Sequence 1 (S1) - clastic limestones with travertine, grey carbonates and oolitic limestones, carbonatic shales and lignites, deposited in a lacustrine environment, originating from debris flows in a tectonic lake. From this sequence gastropods are abundant, while woods, reptiles and mammals are scarce.[11]

- Sequence 2 (S2) - carbonates filling caverns and dissolution cracks on a karstic surface of Sequence 1, comprising fossiliferous marls, deposited in an alluvial to lacustrine environment, transported into these cavities by heavy rains and gravitational flows[11]

- Sequence 3 (S3) - terrestrial siliciclastic sediments, including mudstones, sandstones and sandy conglomerates of Late Eocene to Early Oligocene age, derived from the surrounding basement gneisses, deposited by mudflows in a subaerial alluvial fan environment. These sediments, referred to as the Rio Frio Formation,[1] have been correlated with the Eocene to Oligocene Resende Formation of the eponymous basin.[13]

The Itaboraí Formation is separated from Sequence 3 by basaltic volcanic rocks, formed in the Early Eocene.[16]

Thin section analysis suggests the travertine sequence went through a series of diagenetic processes: firstly, the deposition of the primary carbonate, followed by a set of percolating iron oxide enriched fluids and lastly a set of silica-rich fluids leading to the silica chalcedony and micro-crystalline deposition.[17]

Age

The Itaboraí Formation, defining the Itaboraian SALMA, was first thought to be early to mid Paleocene in age, until dating performed by Woodburne et al. in 2014 suggested as a more probable early Eocene age (53–50 Ma),[18][19] spanning polarity chron 23.[20] The overlying basalts have been dated to the Early Eocene (52.6 ± 2.4 Ma). Another very important source of data is palynological analysis of a coal-bearing horizon (lignite) interlayered with alluvial fan deposits at the northern border of the Itaboraí Basin, suggesting a Paleocene to Eocene age.[21] During this time, a biogeographical connection existed with Antarctica and, though separated by the developing South Atlantic, with Africa.[22] The deposits of the formation were formed during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO), just after the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum.[23]

Paleontological significance

The Itaboraí Formation is the richest and one of few formations in Brazil providing Paleogene mammal faunas, between the older Tiupampan Maria Farinha Formation of the Parnaíba Basin and the younger Divisaderan Guabirotuba Formation of the Curitiba Basin, the Tinguirirican Entre-Córregos Formation of the Aiuruoca Basin and the Deseadan Tremembé Formation of the Taubaté Basin.[24]

Despite its relatively small size, the São José de Itaboraí Basin comprises a diversified fossil assemblage. Among the groups found there, fossil birds are very rare, mainly due to their pneumatized bones. Only three bird species have been described up to this moment from the Itaboraí Basin. Diogenornis fragilis, a probable ratite ancestor, stands out for its good preservation and the number of specimens preserved.[25] In the Paleocene of the southern hemisphere, small terrestrial birds have only been discovered in the late Paleocene fissure fillings of the Itaboraí Formation.[7]

The relative fossil diversity of the Itaboraí Formation at family level consists of 44% mammals, 23% mollusks, 14% reptiles (lizards, chelonians, crocodyliforms), 7% birds, 5% amphibians and 7% plants.[26] Fish are one of the few groups not found to date in the lacustrine formation.[27] The formation has provided many marsupials and related metatherians. The species Lamegoia conodonta is the largest "condylarth" at Itaboraí and approximates the size of a wolf. Ricardocifellia protocenica, originally described as Paulacoutoia protocenica, is the smallest of the "condylarth" species of Itaboraí, but the most abundant.[28] The most abundant litoptern found in the formation is Protolipterna ellipsodontoides.[29]

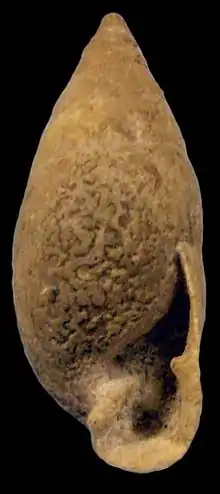

Sequence 1 of the formation has provided many land snails, among which several new species. The records of Itaboraí are the oldest for the genera Austrodiscus, Brachypodella, Bulimulus, Cecilioides, Cyclodontina, Eoborus, Gastrocopta, Leiostracus, Plagiodontes and Temesa. Also, the formation contains the oldest record for the families Orthalicidae, Gastrocoptidae, Ferussaciidae and Strophocheilidae.[30]

Several genera and species were named after the formation; the marsupials Itaboraidelphys camposi and Carolopaulacoutoia itaboraiensis, the birds Itaboravis elaphrocnemoides, Eutreptodactylus itaboraiensis and Eutreptodactylus itaboraiensis, the snake Itaboraiophis depressus and crocodile Eocaiman itaboraiensis and the gastropods Itaborahia lamegoi, Biomphalaria itaboraiensis and Gastrocopta itaboraiensis.

Because of its paleontological importance, the Itaboraí Basin area was designated as a paleontological park in 1995: Parque Paleontológico de São José de Itaboraí ("São José de Itaboraí Paleontological Park").[31] The park was established to preserve the geology and highlight the importance of the paleontological richness of the area.[32]

The formation is named as one of the fossil sites of potential World Heritage Value by the IUCN in 1996.[33]

Fossil content

Fossils recovered from the formation include:[34][35][36][37]

Itaboraian correlations

| Formation | Itaboraí | Las Flores | Koluel Kaike | Maíz Gordo | Muñani | Mogollón | Bogotá | Cerrejón | Ypresian (IUCS) • Wasatchian (NALMA) Bumbanian (ALMA) • Mangaorapan (NZ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | Itaboraí | Golfo San Jorge | Salta | Altiplano Basin | Talara & Tumbes | Altiplano Cundiboyacense | Cesar-Ranchería |  Itaboraí Formation (South America) | |

| Country | |||||||||

| Carodnia | |||||||||

| Gashternia | |||||||||

| Henricosbornia | |||||||||

| Victorlemoinea | |||||||||

| Polydolopimorphia | |||||||||

| Birds | |||||||||

| Reptiles | |||||||||

| Fish | |||||||||

| Flora | |||||||||

| Environments | Alluvial-lacustrine | Alluvial-fluvial | Fluvio-lacustrine | Lacustrine | Fluvial | Fluvio-deltaic | |||

| Volcanic | Yes | ||||||||

See also

- South American land mammal ages

- Iguape Formation, contemporaneous formation of the Santos Basin

- Laguna del Hunco Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin, Argentina

- Lefipan Formation, pre-Tiupampan fossiliferous lacustrine formation of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin, Argentina

- Bogotá Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of central Colombia

- Green River Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Colorado, Wyoming and Utah

- Klondike Mountain Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Washington State

- La Meseta Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Antarctica

References

- Riccomini et al., 2004, p.401

- Kellner & Campos, 1999, p.399

- Bragança Júnior, 1992

- Carvalho, 1987, p.47

- Riccomini et al., 2004, p.390

- Santos & Carvalho, 2012, p.332

- Mayr et al., 2011, p.679

- Riccomini, 1990, p.68

- Kellner & Campos, 1999, p.246

- Riccomini et al., 2004, p.384

- Oliveira & Goin, 2011, p.107

- Modenesi-Gauttieri et al., 2002, p.258

- Oliveira & Goin, 2011, p.108

- Torres Tiago, 2017, p.25

- Torres Tiago, 2017, p.26

- Torres Tiago, 2017, p.27

- Valente et al., 2017, p.227

- Oliveira et al., 2016, p.2

- Woodburne et al., 2014, p.116

- Woodburne et al., 2014, p.112

- Oliveira & Goin, 2011, p.109

- Ezcurra & Agnolín, 2012, p.560

- Woodburne et al., 2013, p.7

- Sedor, 2017, p.39

- De Taranto et al., 2011, p.R58

- Pinheiro et al., 2013, p.328

- Bergqvist & Bastos, 2011, p.370

- Bergqvist, 2008, p.107

- Bergqvist, 2008, p.108

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.42

- Pinheiro et al., 2013, p.329

- Bergqvist & Bastos, 2011, p.367

- Wells, 1996, p.35

- Itaboraí snakes at Fossilworks.org

- Portland Quarry at Fossilworks.org

- São José de Itaboraí at Fossilworks.org

- São José 700 m at Fossilworks.org

- Carneiro, 2019, p.5

- Oliveira, 1998, p.148

- Ladevèze & De Muizon, 2010, p.759

- Carneiro & Oliveira, 2017a, p.357

- Goin & Oliveira, 2007, p.310

- Oliveira & Goin, 2015, p.99

- Oliveira & Goin, 2015, p.101

- Oliveira et al., 2016, p.4

- Carneiro et al., 2018, p.121

- Goin et al., 2016, p.85

- Oliveira & Goin, 2011, p.114

- Oliveira & Goin, 2011, p.112

- Goin et al., 2016, p.86

- Ladevèze, 2004, p.202

- Ladevèze & De Muizon, 2010, p.747

- Carneiro & Oliveira, 2017b, p.499

- Carneiro et al., 2018, p.122

- Bergqvist et al., 2004, p.325

- Oliveira & Bergqvist, 1998, p.36

- Bergqvist, 2010, p.858

- Goin et al., 2016, p.87

- Bergqvist, 2008, p.119

- Bergqvist, 2008, p.113

- Mones, 2015, p.1

- Bergqvist, 2010, p.860

- Bergqvist, 2010, p.861

- Bergqvist, 2010, p.859

- Bergqvist, 2008, p.124

- Goin et al., 2016, p.89

- Beck, 2016, p.8

- Mayr et al., 2011, p.682

- Mayr et al., 2011, p.680

- Rage, 1998, p.133

- Rage, 1998, p.131

- Rage, 2001, p.122

- Rage, 2001, p.116

- Rage, 2008, p.46

- Rage, 2008, p.41

- Rage, 2008, p.52

- Rage, 2001, p.130

- Rage, 2001, p.126

- Rage, 1998, p.116

- Rage, 2008, p.58

- Kellner et al., 2014, p.2

- Pinheiro et al., 2013, p.330

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.12

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.28

- Salvador & Simone, 2013b, p.4

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.26

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.9

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.11

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.15

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.16

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.14

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.17

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.21

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.25

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.23

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.24

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.27

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.19

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.22

- Salvador & Simone, 2013a, p.13

Bibliography

- General

- Bergqvist, Lílian Paglarelli, and Ana Carolina Fortes Bastos. 2011. A utilização de atividades lúdicas na divulgação da importância do Parque Paleontológico de São José, Itaboraí/RJ. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 41. 366–374. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Bragança Júnior, Álvaro Alfredo. 1992. A morfologia sufixal indígena na formação de topônimos do estado do Rio de Janeiro (M.A. thesis), 1. Universidade de Rio de Janeiro. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Carvalho, Moacyr Ribeiro de. 1987. Dicionário tupi (antiguo)-portugues, 1–314. _. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Dos Santos, Wellington Francisco Sá, and Ismar de Souza Carvalho. 2012. Parque Paleontológico de São José de Itaboraí (Brasil): Propostas para a Preservação do Patrimônio a partir das Opiniões da População de Cabuçu in Para Aprender com a Terra, 331–340. Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Valente, Brenda Da Silva; Gustavo C.R. Pereira; Emiliano Castro Oliveira, and Sergio Bergamaschi. 2017. Petrographic Study of Silica-rich Continental Carbonates from São José de Itaboraí Basin (Brazil). Journal of Sedimentary Environments 2. 219–228. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Geology

- Ezcurra, Martín D., and Federico Agnolín. 2011. A New Global Palaeobiogeographical Model for the Late Mesozoic and Early Tertiary. Systematic Biology 61. 553–566. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Modenesi-Gauttieri, May Christine; Silvio Takashi Hiruma, and Claudio Riccomini. 2002. Morphotectonics of a high plateau on the northwestern flank of the Continental Rift of southeastern Brazil. Geomorphology 43. 257–271. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Riccomini, Claudio; Lucy Gomes Sant'Anna, and André Luiz Ferrari. 2004. Evolução geológica do rift continental do sudeste do Brasil in Geologia do continente Sul-Americano: evolução da obra de Fernando Flávio de Almeida, 383–406. Beca. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Riccomini, Claudio. 1990. O Rift Continental do Sudeste do Brasil (PhD thesis), 1–319. Universidade de São Paulo. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Torres Tiago, Nina. 2017. Caracterização mineralógica e petrológica das ocorrências de ankaramito nas Bacias de Itaboraí Volta Redonda - RJ (BS thesis), 1–76. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Accessed 2019-04-04. (in Portuguese)

- Paleontology

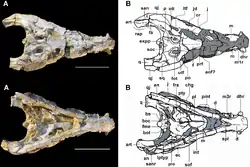

- Beck, Robin M. 2016. The Skull of Epidolops ameghinoi from the Early Eocene Itaboraí Fauna, Southeastern Brazil, and the Affinities of the Extinct Marsupialiform Order Polydolopimorphia. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 24. 1–43. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Bergqvist, Lílian Paglarelli. 2010. Deciduous premolars of Paleocene Litopterns of São José de Itaboraí Basin, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Journal of Paleontology 84. 858–867. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Bergqvist, Lílian Paglarelli. 2008. Postcranial Skeleton of the Upper Paleocene (Itaboraian) "Condylarthra" (Mammalia) of Itaboraí Basin, Brazil in Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology - a tribute to A Tribute to Frederick S. Szalay, 107–133. Springer. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Bergqvist, Lílian Paglarelli; Érika Aparecida Leite Abrantes, and Leonardo dos Santos Avilla. 2004. The Xenarthra (Mammalia) of Sao Jose de Itaborai Basin (upper Paleocene, Itaboraian), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Geodiversitas 26. 323–337. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Bond, M.; A.A. Carlini; F.J. Goin; L. Legarreta; E. Ortiz Jaureguizar; R. Pascual, and M.A. Uliana. 1995. Episodes in South American Land Mammal Evolution and Sedimentation: Testing Their Apparent Concurrence in a Paleocene Succession from Central Patagonia, 47–58. VI Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Carneiro, Leonardo M.; Édison V. Oliveira, and Francisco J. Goin. 2018. Austropediomys marshalli gen. et sp. nov., a new Pediomyoidea (Mammalia, Metatheria) from the Paleogene of Brazil: paleobiogeographic implications. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 21. 120–131. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Carneiro, Leonardo M.. 2018. A new protodidelphid (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Didelphimorphia) from the Itaboraí Basin and its implications for the evolution of the Protodidelphidae. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 91(Suppl. 2). e20180440. Accessed 2019-04-04. Archived 2019-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Carneiro, Leonardo M., and Édison V. Oliveira. 2017a. Systematic affinities of the extinct metatherian Eobrasilia coutoi Simpson, 1947, a South American Early Eocene Stagodontidae: implications for "Eobrasiliinae". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 20. 355–372. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Carneiro, Leonardo M., and Édison Vicente Oliveira. 2017b. The Eocene South American metatherian Zeusdelphys complicatus is not a protodidelphid but a hatcheriform: Paleobiogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62. 497–507. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Goin, Francisco J.; Michael O. Woodburne; Ana Natalia Zimicz; Gabriel M. Martin, and Laura Chornogubsky. 2016. Dispersal of Vertebrates from Between the Americas, Antarctica, and Australia in the Late Cretaceous and Early Cenozoic in A Brief History of South American Metatherians: Evolutionary Contexts and Intercontinental Dispersals, 77–124. Springer. Accessed 2019-04-04. ISBN 978-94-017-7420-8

- Goin, Francisco J., and Édison V. Oliveira. 2007. A new species of Gashternia (Marsupialia) from Itaboraí (Brazil). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 245. 309–313. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Goin, Francisco J.; Édison V. Oliveira, and Adriana M. Candela. 1998. Carolocoutoia ferigoloi nov. gen. and sp. (Protodidelphidae), a new Paleocene "opossum-like" marsupial from Brazil. Palaeovertebrata 27. 145–154. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Kellner, Alexander W.A.; André E.P. Pinheiro, and Diogenes A. Campos. 2014. A New Sebecid from the Paleogene of Brazil and the Crocodyliform Radiation after the K–Pg Boundary. PLoS ONE 9. 1–11. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Kellner, Alexander W.A., and Diogenes A. Campos. 1999. Vertebrate paleontology in Brazil — a review. Episodes 22. 238–251. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Ladevèze, Sandrine, and Christian De Muizon. 2010. Evidence of early evolution of Australidelphia (Metatheria, Mammalia) in South America: Phylogenetic relationships of the metatherians from the Late Palaeocene of Itaboraí (Brazil) based on teeth and petrosal bones. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159. 746–784. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Ladevèze, Sandrine. 2004. Metatherian petrosals from the Late Paleocene of Itaboraí (Brazil), and their phylogenetic implications. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24. 202–213. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Mayr, Gerald; Herculano Alvarenga, and Julia A. Clarke. 2011. An Elaphrocnemus−like landbird and other avian remains from the late Paleocene of Brazil. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56. 679–684. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Mones, Álvaro. 2015. Ricardocifellia, a replacement name for Paulacoutoia Cifelli, 1983, and Depaulacoutoia Cifelli and Ortiz-Jaureguizar, 2014 (Mammalia, 'Condylarthra', Didolodontidae), and the status of Depaulacoutoia Kretzoi and Kretzoi, 2000 (Mammalia, Australidelphia, Polydolopimorphia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology e973571. 1. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Oliveira, Édison Vicente; Natalia Zimicz, and Francisco J. Goin. 2016. Taxonomy, affinities, and paleobiology of the tiny metatherian mammal Minusculodelphis, from the early Eocene of South America. The Science of Nature 103(1–2). 1–6. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Oliveira, Édison Vicente, and Francisco J. Goin. 2015. A new species of Gaylordia Paula Couto (Mammalia, Metatheria) from Itaboraí, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 18(1). 97–108. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Oliveira, Édison V., and Francisco J. Goin. 2011. A reassessment of Bunodont Metatherians from the Paleogene of Itaboraí (Brazil): systematics and age of the Itaboraian SALMA. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 14. 105–136. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Oliveira, Édison Vicente, and Lílian Paglarelli Bergqvist. 1998. A new Paleocene armadillo (Mammalia, Dasypodoidea) from the Itaboraí Basin, Brazil. Asociación Paleontológica Argentina Publicación Especial 5. 35–40. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Pinheiro, André E.P.; Daniel C. Fortier; Diego Pol; Diógenes A. Campos, and Lílian P. Bergqvist. 2013. A new Eocaiman (Alligatoridae, Crocodylia) from the Itaboraí Basin, Paleogene of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Historical Biology 25. 327–337. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Rage, Jean-Claude. 1998. Fossil snakes from the Palaeocene of São José de Itaboraí, Brazil. Part I. Madtsoiidae, Aniliidae. Palaeovertebrata 27. 109–144. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Rage, Jean-Claude. 2001. Fossil snakes from the Palaeocene of São José de Itaboraí, Brazil. Part II. Boidae. Palaeovertebrata 30. 111–150. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Rage, Jean-Claude. 2008. Fossil snakes from the Palaeocene of São José de Itaboraí, Brazil. Part III. Ungaliophiinae, Booids incertae sedis, and Caenophidia. Summary, update, and discussion of the snake fauna from the locality. Palaeovertebrata 36. 37–73. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Salvador, R.B., and L.R.L. Simone. 2013a. Taxonomic revision of the fossil pulmonate mollusks of Itaboraí Basin (Paleocene), Brazil. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 53(2). 5–46. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Salvador, R.B., and L.R.L. Simone. 2013b. A malacofauna fóssil da Bacia de Itaboraí, Rio de Janeiro: histórico dos estudos e perspectivas para o futuro. Revista da Biologia 11. 1–6. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Sedor, Fernando A.; Eliseu Vieira Dias; Renata Floriano Da Cunha, and Herculano Alvarenga. 2014. Paleogene phorusrhacid bird (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the Guabirotuba Formation, Curitiba Basin, Paraná, South of Brazil, 807. 4th International Palaeontological Congress. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- De Taranto, R.C.; M.F. Loguercio; L.P. Bergqvist, and O. Rocha Barbosa. 2011. Comparative analysis of the hindlimb morphology of Diogenornis fragilis (Aves, Ratites - Paleocene) and flightless extant and extinct birds. Ameghiniana 48. R58. .

- Wells, Roderick T. 1996. Earth's Geological History - a contextual framework for assessment of World Heritage fossil site nominations - a Contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites, 1–43. IUCN. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Woodburne, Michael O.; Francisco J. Goin; Maria Sol Raigemborn; Matt Heizler; Javier N. Gelfo, and Édison V. Oliveira. 2014. Revised timing of the South American early Paleogene Land Mammal Ages. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 54. 109–119. Accessed 2019-04-04.

- Woodburne, M.O.; F.J. Goin; M. Bond; A.A. Carlini; J.N. Gelfo; G.M. López; A. Iglesias, and A.N. Zimicz. 2013. Paleogene Land Mammal Faunas of South America; a Response to Global Climatic Changes and Indigenous Floral Diversity. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 21. 1–73. Accessed 2019-04-04.