Pyrotherium

Pyrotherium ('fire beast') is an extinct genus of South American ungulate, of the order Pyrotheria, that lived in what is now Argentina and Bolivia, during the Late Oligocene.[1] It was named Pyrotherium because the first specimens were excavated from an ancient volcanic ash deposit. Fossils of the genus have been found in the Deseado and Sarmiento Formations of Argentina and the Salla Formation of Bolivia.

| Pyrotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| P. romeroi skull in Beneski Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Pyrotheria |

| Family: | †Pyrotheriidae |

| Genus: | †Pyrotherium Ameghino, 1888 |

| Type species | |

| †Pyrotherium romeroi Ameghino, 1888 | |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

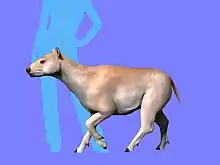

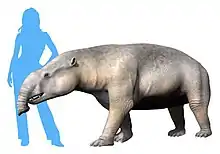

So far, two valid species have been described, Pyrotherium romeroi, which lived in what it is today Argentina and P. macfaddeni from Bolivia, at the end of Oligocene. P. romeroi in particular is the most recent known pyrothere in the fossil record and best known for its fossil remains, which although incomplete are the best preserved in the entire order, indicating that they are also the largest, with an estimated body length from 2.9 to 3.6 meters (9.5 to 11.8 ft).[2] It is also supposed to have developed a small trunk,[3] but it is not related to the current elephants (proboscideans); the resemblance is so great that when studying the fossil remains, it was attributed in the past a relationship with elephants, although the true relationship of this herbivore is still controversial today.[2]

Discovery and naming

The original remains of Pyrotherium, some molars, a premolar and an incisor, were originally identified in the Neuquén province in strata dating back to the late Oligocene epoch, identified by the Argentine naturalist Florentino Ameghino as couche à Pyrotherium (layers of Pyrotherium, in French) due to the presence of fossils of this animal that were the first to be identified there;[4][5] these strata are now known as part of the Deseadan mammal-age (SALMA) in the area of the Deseado estuary, although there is the doubt whether the holotype of Pyrotherium romeroi really comes from Neuquén, it being possible that the remains actually came from Chubut.[6] Ameghino considered that these areas corresponded to older terrains, from the Paleocene[7] and even from the Cretaceous, because they were sent together with dinosaur remains;[8] subsequent studies have shown that they actually come from the Oligocene, and in fact the Pyrotherium fossils have reached become the guide fossil of the late Oligocene. Because the remains of this animal originally appeared in the volcanic ash beds of the Deseado Formation, they gave rise to the name of the genus, which means "fire beast".[9]

The name of the species P. romeroi is due to the captain of the Argentine army Antonio Romero who sent Ameghino the first known remains of the animal, although in several texts the erroneous spellings P. romeri or P. romerii has been used.[7] Ameghino named several species from the Deseado area such as P. sorondoi based on partial remains, mainly teeth, but later studies indicated that they are part of a single species.[9][10] The first relatively complete skull did not appear until the 20th century, being discovered by Frederic Brewster Loomis during the Amherst College expedition in 1911-1912, and listed as specimen ACM 3207.[11]

Additional remains of the genus have appeared in Quebrada Fiera, from the Mendoza province (Argentina) and in Salla, in the department of La Paz in Bolivia; the latter consist of the remains of a partial jaw, fragments of skull bones, teeth, and some limb bone such as pieces of the humerus and astragalus, which were found between the 1960s and 1980s and were initially considered part of the species P. romeroi,[12] and later they were classified as a different and smaller species, P. macfaddeni, whose species name is in honor of paleontologist Bruce J. MacFadden.[9] Molar and postcranial bone remains found in sediments from the late Oligocene of Taubaté, Brazil were considered as a possible finding of Pyrotherium,[13] but it is possible that they correspond to some different genus with which it is closely related, but not yet described.[14]

Description

Skull

The skull of Pyrotherium romeroi was long and narrow, made up of massive bones. It reaches 72 centimeters (2.36 ft) in length from its front teeth to its occipital condyle, and has an elongated, relatively narrow snout seen from above, with retracted nostrils, a large nasal opening located between the eye sockets in the middle of the front bone, in parallel to the back of the skull, with thick bone walls for muscle support; inside there are cavities filled with air. The occipital region, in particular the condyles, was particularly high, as a consequence of the flexion of the posterior part of the skull with respect to the plane of the base, which formed an obtuse angle with that of the palatine bone; in this and other characteristics, Pyrotherium resembled proboscideans. There is a small ridge that emerges from the premaxilla and reaches the nasal bone, which appears to be broken and surrounded by a rough texture, which could be the result of erosion. How large it may have been is unknown, as it may have been only a prominence similar to that seen in the narial process of the notoungulates and rodents, or even almost a ridge; this ridge is not known in other mammals, but perhaps it served as a holding point for the muscles of a possible proboscis or trunk. The brain cavity (neurocranium) is damaged and surrounded by spongy bone tissue; Loomis considered that it indicated that in life P. romeroi had a small brain, about 150 millimeters (5.9 in) long and 50 millimeters (2.0 in) wide.[11] Later analysis by Bryan Patterson in 1977, after some additional preparation work on the only known skull, indicated some errors in earlier interpretations, and that the brain would be somewhat larger, 80 millimeters wide, more similar in size to that of notoungulates such as Homalodotherium and Nesodon.[10]

Another very distinctive feature is the presence of two pairs of large front-facing incisors, in the form of tusks and arranged at a 45° angle. These showed continuous growth and were equipped with an enamel band only on the front. It lacked canines, and it also has peculiar premolars and molars, with two transverse high ridges (bilophodonts), whose general appearance is reminiscent of tapir molars. Between the incisors and the posterior teeth there was a space without teeth, the diastema, reaching 46 millimeters (1.8 in) long. The teeth in general, and particularly the posterior ones, also occupied a lot of the skull area, particularly in the palate. The auditory region is situated much higher than the palate in lateral view and curves upwards in its posterior part.[15] In P. macfaddeni the premaxilla has an additional pair of very small alveoli, suggesting that it may have had a third pair of barely developed incisors, and their molars are distinguished by having a well-defined valley that separates the anterior and posterior lophs.[9]

The dental formula in P. romeroi is 2.0.3.31.0.2.3 × 2 = 28 (2I/0C/3PM/3M, 1i/0c/2pm/3m)[15]

The mandible was robust and had a well-developed, long and narrow symphysis extending to the second molar, a marked foramen posterior to the third molar, and a large maseteric fossa. It only has only two incisors, which protrude forward and are oriented like the upper incisors at a 45° angle, making contact with the tips of these; it has been thought that these could be the second incisors (i2), but their actual identification is uncertain. At least in P. macfaddeni have a layer of enamel that only covers the ventral part of the incisors.[9] As in the maxilla, it has bilophodont premolars and molars; the structure of the molars is reminiscent of that found in other large archaic mammals, such as dinocerates, Barytherium and deinotheriids.[15]

Postcranium

_BHL21733685.jpg.webp)

Some postcranial bones of Pyrotherium romeroi have been recovered, mainly from the limbs. The vertebral column is very poorly known; the remains found mainly include cervical vertebrae, including the atlas, the axis and the third and fourth vertebrae, all of which are very short. Additionally, a lumbar vertebra is known, which is massive and with a reduced spine, somewhat similar to that of Astrapotherium. A fragment of the shoulder blade indicates that it was short and strong; the glenoid cavity was twice its length and the acromion was very high.[11]

The humerus is relatively short, 497 to 500 millimeters in length, but extremely wide, with great insertions for the muscles; the ulna and radius are also known, both even shorter, about 225 millimeters, and the ulna also had a large olecranon.[11] Likewise, two bones of the wrist have been identified, the right unciform and the left great, both being elements short but thick and trapezoidal in appearance.[16] A pyramidal and semilunate have also been found. Also included is an astragalus and calcaneus, and a femur.[11]

The pelvis was equipped with a massive iliac bone, with an acetabulum located downwards and not laterally. The femur lacked the third trochanter, with a straight head much higher than the greater trochanter, and was flattened anteroposteriorly; in this species it reached 630 millimeters in length, being greater than the only other femur known between the pyrotheres, the one of Baguatherium, which reached 558 millimeters.[17] The shape of the distal joint allowed the tibia to move backwards widely, which compensated for the lack of flexibility in the foot joint. The tibia was much shorter than the femur, and the fibula was very close to the tibia, except in the central part. The astragalus was strongly flattened, very simple in appearance, and neckless, with a slightly hinted tibial trochlea and a facet of the navicular located directly below the trochlea. The tarsus of Pyrotherium was characteristic: the calcaneus tubercle was compressed dorsoventrally, as was the trochlea of the astragalus; in addition, it presents an extreme reduction in the contact between the heel and the cuboid.[11] These derived characteristics, which involve a type of graviportal and plantigrade locomotion, are not found in any other known mammal, with the significant exception of the African Arsinoitherium.[9]

Phylogeny

Because Pyrotherium has the characteristic bilophodont posterior teeth (that is, with two ridges), tusks formed by its upper and lower incisors, a huge and robust body along with the possible presence of a trunk, it was proposed in the past that it was a close relative of the proboscideans, or even a member of that group (Ameghino 1895, 1897; Lydekker 1896;[18] Loomis 1914).[11] Loomis 1921[19] However, the mixture of characteristics of the animal is such that it has led to comparing and relating it at different times with other groups, such as the marsupial diprotodontids (Lydekker 1893;[20] Loomis 1921), the amblipodan pantodonts (Zittel 1893),[21] perissodactyls (Ameghino, 1888),[22] the notoungulates (Osborn 1910; Loomis 1914;[11] Scott 1913; Patterson 1977),[10] the xenungulates (Simpson 1945; Cifelli 1983; Lucas 1986, 1993), and the dinoceratans via their supposed relationship with xenungulates (Lucas 1986, 1993);[23] in some studies, the complete study of the tarsus of Pyrotherium fails to support a relationship with xenungulatans, instead the derived characteristics of Pyrotherium were not observed other than in other mammals examined except for the embrithopod Arsinoitherium from the Paleogene of Africa. If this is due to a common ancestor, or to the unusual mode of locomotion used by these animals (graviportal and plantigrade) remains a mystery to be seen.[9] However, Gaudry (1909) himself established that Pyrotherium was sufficiently different from any other group of large mammals that it should have its own order, with no clear relation to other mammals.[24] The most recent analysis published out, like the work of Billet in 2010, suggests that pyrotheres such as Pyrotherium are a group of specialized notoungulates, related to Notostylops,[15][25] although this is still a controversial idea.[2]

Cladogram based on the phylogenetic analysis of Cerdeño et al., 2017, highlighting the location of both species of Pyrotherium:[16]

| Notoungulata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The Pyrotherium's bilophodont molariform teeth were examined to determine their dental enamel type, using an electronic microscope to examine their prisms. Examinations showed that its enamel follows a strange keyhole pattern, also known as Boyde pattern, in which the prisms are densely clustered with no interprismatic matrix between them. This type of prism in the enamel is characteristic of pyrotheres and is not known in the other orders of native South American ungulates (xenungulates, astrapotheres, litopterns, and notoungulates). In P. romeroi, the enamel also has a distinctive kind, just called "Pyrotherium's enamel" in which the enamel bands are arranged vertically with the prisms in a decoupled way (that is, forming patterns in "X").[26]

This analysis also made it possible to infer the chewing patterns of Pyrotherium. This would be dominated by the so-called phase 1, in which the mandible is tilted and directed mesially, while the cutting ridges of the molars were compressing the food bolus. Then a phase 2 was developed, in which the jaw moved laterally; this move seems to have been less significant. This type of chewing and molars resembles that observed in some other mammals, such as the Macropus kangaroos, the perissodactyl Lophiodon, the marsupial Diprotodon and the proboscidean Deinotherium, but in these animals their enamel (and molar lophs) wear out quickly into adulthood, leaving a flat surface for grinding, whereas in Pyrotherium the lophs are much more resistant and can be clearly seen even in elderly individuals, in whom the worn molars still have sharp ridges. A similar condition is only seen in embrithopods such as Arsinoitherium, which also has vertically arranged enamel and in Namatherium, which closely resembles Pyrotherium in this respect by having enamel and highly inclined enamel facets.[26]

Due to the robust structure of the animal, it was most likely a graviportal quadruped, that is, an animal weighing more than a ton whose physical structure is prepared to support that great mass, but not for speed.[27] With a weight of 900 kg (2,000 lb) in P. macfaddeni to 3.5 t (7,700 lb) in P. romeroi based on estimates of its molars, and 600–700 kg (1,300–1,500 lb) in P. macfadeni at 1.8 to 2.7 t (4,000 to 6,000 lb) for P. romeroi with base in equations derived from the head-body ratios,[2] Pyrotherium was among the largest native mammals in South America. Its bones are extremely dense, even more than in other large meridiungulates such as the notoungulate toxodonts and astrapotheres, which implies an extreme specialization towards graviportality; X-ray microtomography analysis of the bone density of its humerus and femur indicate that its medullary area was particularly compact, almost comparable to the pachyostosis of aquatic or semiaquatic mammals, with thick trabeculae and very small intratrabecular cavities, although they resemble externally the bones of proboscideans or rhinos, which would help it better absorb the impact energy on the bones.[28] It is also inferred that its posture would have been semi-plantigrade, since the fingers of the hands would support its weight, but instead the feet they would have been plantigrade, as inferred from the ankle bones.[16]

Paleoecology

The Pyrotherium fossils recovered from both Salla, Deseado and Quebrada Fiera correspond to relatively dry environments, with xerophytic vegetation and periods of drought;[29] this would contradict the hypothesis that they were semiaquatic animals, similar to hippopotamuses, while the remains of astrapotheres (another group of large, tusked native ungulates) are in fact found in areas associated with bodies of water, which would imply that they would live in humid environments and were able to spend some time in the water.[28] Pyrotherium would have used its incisors and trunk in order to collect food such as leaves and branches of the trees, in a similar way to black rhinos and African forest elephants.[29]

Pyrotherium cohabited with several other mammals, several of them large that are typical of the Deseadan fauna of places like La Flecha in Argentina. The presence of predatory sparassodonts such as Pharsophorus, Notogale and the enormous Proborhyaena is noteworthy, and other ungulates which were mainly notoungulates, such as Trachytherus, Leontinia, Rhynchippus, Propachyrucos, Argyrohyrax, Archaeohyrax, and Prohegetotherium.[30]

References

- Pyrotherium at Fossilworks.org

- Croft, D. A.; Gelfo, J. N.; López, G. M. (2020). "Splendid Innovation: The Extinct South American Native Ungulates". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 48.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 249. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Ameghino, F. 1894. Première contribution à la conaissance de la faune mammalogique des couches à Pyrotherium. Boletín del Instituto Geográfico Argentino 15: 603–660.

- Ameghino C. 1914. Le Pyrotheríum, I'étage Pyrothéréen et les couches á Notostylops. Une response á Mr. Loomis. Physis, 1: 446-460.

- Kramarz, A. G., Forasiepi, A. M., & Bond, M. (2011). Vertebrados cenozoicos. In Relatorio del XVIII Congreso Geológico Argentino. Geología y Recursos Naturales de la Provincia del Neuquén (pp. 557-572). Buenos Aires: Asociación Geológica Argentina.

- Ameghino, F. 1889. Contribución al conocimiento de los mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina, obra escrita bajo los auspicios de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de la República Argentina para presentarla a la Exposición Universal de París de 1889. Actas Academia de Ciencias de Córdoba 6:1–1027.

- F. Ameghino. 1897. Mammiféres crétacés de l'Argentine (Deuxième contribution à la connaissance de la fauna mammalogique de couches à Pyrotherium) [Cretaceous mammals of Argentina (second contribution to the knowledge of the mammalian fauna of the Pyrotherium Beds)]. Boletín Instituto Geográfico Argentino 18(4–9):406-521

- Shockey, B.J. & Anaya, F. (2004). "Pyrotherium macfaddeni, sp. nov. (Late Oligocene, Bolivia) and the pedal morphology of pyrotheres". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 481–488. doi:10.1671/2521. S2CID 83680724.

- Patterson, B. 1977. A primitive pyrothere (Mammalia, Notoungulata) from the Early Tertiary of Northwestern Venezuela. Fieldiana, Geology 33: 397–422.

- Loomis, F.B. 1914. The Deseado Formation of Patagonia. Amherst College, Amherst, 232659 p.

- MacFadden BJ, Frailey CD (1984) Pyrotherium, a large enigmatic ungulate (Mammalia, incertae sedis) from the Deseadan (Oligocene) of Salla, Bolivia. Palaeontol 27:867–874

- Couto-Ribeiro, G. and Alvarenga, H. 2009. Primeiro registro de dentes de Pyrotherium para a Formação Tremembé, Bacia de Taubaté, SP. Reunião Anual da Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia. Núcleo São Paulo. Abstracts: 21.

- Ribeiro, G. D. C. Osteologia de Taubatherium paulacoutoi Soria & Alvarenga, 1989 (Notoungulata, Leontiniidae) e de um novo Pyrotheria: dois mamíferos fósseis da Formação Tremembé, Brasil (SALMA Deseadense-Oligoceno Superior). (Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo).

- Billet, G. 2010. New observations on the skull of Pyrotherium (Pyrotheria, Mammalia) and new phylogenetic hypotheses on South American ungulates. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 17: 21–59.

- Cerdeño, E., & Vera, B. (2017). New Anatomical Data on Pyrotherium (Pyrotheriidae) from the Late Oligocene of Mendoza, Argentina. Ameghiniana, 54(3), 290-306.

- Salas, R., Sánchez, J. and Chacaltana, C. 2006. A new pre-Deseadan pyrothere (Mammalia) from Northern Peru and the wear facets of molariform teeth of Pyrotheria. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26: 760–769.

- Lydekker, R. 1896. A Geographical History of Mammals. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 400 pp.

- Loomis, F. B. 1921. Origin of South American faunas. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 32:187–196.

- Lydekker, R. 1894. Contribuciones al conocimiento de los vertebrados fósiles de Argentina. 1. Observaciones adicionales sobre los ungulados argentinos. Anales del Museo de La Plata 2: 1–91

- Zittel, K. A. 1893. Handbuch der Palaeontologie. IV. Band: Vertebrata (Mammalia). Druck und verlan von R. Oldenbourg, Munchen und Leipzig.

- Ameghino, F. 1888. Rápidas diagnosis de algunos mamíferos fósiles nuevos de la República Argentina. P.E. Coni, Ed., Buenos Aires, 17 p.

- Spencer, L. (1986). Pyrothere sistematics and a caribbean route for land-mammal dispersal during the Paleocene. Revista Geológica de América Central.

- Gaudry, A. 1909. Fossiles de Patagonie: le Pyrotherium. Annales de Paléontologie 4:1–28.

- Billet, G. 2011. Phylogeny of the Notoungulata (Mammalia) based on cranial and dental characters. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 9: 481–497.

- Koenigswald, W 647 . von, Martin, T. and Billet, G. 2015. Enamel microstructure and mastication in Pyrotherium romeroi (Pyrotheria, Mammalia). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 89: 611–634.

- Johnson, S. C. (1984). Astrapotheres from the Miocene of Colombia, South America. University of California, Berkeley.

- Houssaye, A., Fernández, V., and Billet, G. 2016. Hyperspecialization in some South American endemic ungulates revealed by long bone microstructure. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 23: 221–235.

- Croft, D. A. (2016). Horned armadillos and rafting monkeys: the fascinating fossil mammals of South America. Indiana University Press.

- Marani, H. A. (2005). Los Rhynchippinae de Edad Mamífero Deseadense de la Localidad Cabeza Blanca. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Chubut-Argentina.

Bibliography

- F. Ameghino. 1894. Sur les oiseaux fossiles de Patagonie; et la faune mammalogique des couches à Pyrotherium. Boletín del Instituto Geographico Argentino 15:501-660

- F. Ameghino. 1901. Notices préliminaires sur des ongulés nouveaux des terrains crétacés de Patagonie [Preliminary notes on new ungulates from the Cretaceous terrains of Patagonia]. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba 16:349-429

.jpg.webp)