Van Allen Probes

The Van Allen Probes, formerly known as the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP),[1] were two robotic spacecraft that were used to study the Van Allen radiation belts that surround Earth. NASA conducted the Van Allen Probes mission as part of the Living With a Star program.[2] Understanding the radiation belt environment and its variability has practical applications in the areas of spacecraft operations, spacecraft system design, mission planning and astronaut safety.[3] The probes were launched on 30 August 2012 and operated for seven years. Both spacecraft were deactivated in 2019 when they ran out of fuel. They are expected to deorbit during the 2030s.

Artist's impression of the Van Allen Probes in orbit | |

| Names | Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP) |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Astrophysics |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2012-046A / 2012-046B |

| SATCAT no. | 38752 / 38753 |

| Website | vanallenprobes |

| Mission duration | Planned: 2 years Final: 7 years, 1 month, 17 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Applied Physics Laboratory |

| Launch mass | ~1500 kg for both |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 30 August 2012, 08:05 UTC |

| Rocket | Atlas V 401 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-41 |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| End of mission | |

| Deactivated | Van Allen Probe A: 18 October 2019 Van Allen Probe B: 19 July 2019 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Highly elliptical |

| Semi-major axis | 21,887 km (13,600 mi) |

| Perigee altitude | 618 km (384 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 30,414 km (18,898 mi) |

| Inclination | 10.2° |

| Period | 537.1 minutes |

| |

Overview

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center manages the overall Living With a Star program of which RBSP is a project, along with Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) was responsible for the overall implementation and instrument management for RBSP. The primary mission was scheduled to last 2 years, with expendables expected to last for 4 years. The primary mission was planned to last only 2 years because there was great concern as to whether the satellite's electronics would survive the hostile radiation environment in the radiation belts for a long period of time. When after 7 years the mission ended, it was not because of electronics failure but because of running out of fuel. This proved the resiliency of the spacecraft's electronics. The spacecraft's longevity in the radiation belts was considered a record-breaking performance for satellites in terms of radiation resiliency.[4]

The spacecraft worked in close collaboration with the Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), which can measure particles that break out of the belts and make it all the way to Earth's atmosphere.[5][6]

The Applied Physics Laboratory managed, built, and operated the Van Allen Probes for NASA.

The probes are named after James Van Allen, the discoverer of the radiation belts they studied.[4]

Milestones

- Mission concept review completed, 30–31 January 2007[7]

- Preliminary design review, October 2008

- Confirmation review, January 2009

- Probes transported from Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, 30 April 2012

- Probes launched from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida on 30 August 2012. Liftoff occurred at 4:05 a.m. EDT.[8]

- Van Allen Probe B deactivated, 19 July 2019.

- Van Allen Probe A deactivated, 18 October 2019. End of mission.

Launch vehicle

On 16 March 2009 United Launch Alliance (ULA) announced that NASA had awarded ULA a contract to launch RSBP using an Atlas V 401 rocket.[9] NASA delayed the launch as it counted down to the four-minute mark early morning on 23 August. After bad weather prevented a launch on 24 August, and a further precautionary delay to protect the rocket and satellites from Hurricane Isaac, liftoff occurred on 30 August 2012 at 4:05 AM EDT.[10]

End of mission

On 12 February 2019, mission controllers began the process of ending the Van Allen Probes mission by lowering the spacecraft's perigees, which increases their atmospheric drag and results in their eventual destructive reentry into the atmosphere. This ensures that the probes reenter in a reasonable timespan, in order to pose little threat with regards to the problem of orbital debris. The probes were projected to cease operations by early 2020, or whenever they ran out of the necessary propellant to keep their solar panels pointed at the Sun. Reentry into the atmosphere is predicted to occur in 2034.[11]

Van Allen Probe B was shut down on 19 July 2019, after mission operators confirmed that it was out of propellant.[12] Van Allen Probe A, also running low on propellant, was deactivated on 18 October 2019, putting an end to the Van Allen Probes mission after seven years in operation.[13]

Science

The Van Allen radiation belts swell and shrink over time as part of a much larger space weather system driven by energy and material that erupt off the Sun's surface and fill the entire Solar System. Space weather is the source of aurora that shimmer in the night sky, but it also can disrupt satellites, cause power grid failures and disrupt GPS communications. The Van Allen Probes were built to help scientists understand this region and to better design spacecraft that can survive the rigors of outer space.[2] The mission aimed to further scientific understanding of how populations of relativistic electrons and ions in space form or change in response to changes in solar activity and the solar wind.[2]

The mission's general scientific objectives were to:[2]

- Discover which processes - singly or in combination - accelerate and transport the particles in the radiation belt, and under what conditions.

- Understand and quantify the loss of electrons from the radiation belts.

- Determine the balance between the processes that cause electron acceleration and those that cause losses.

- Understand how the radiation belts change in the context of geomagnetic storms.

In May 2016, the research team published their initial findings, stating that the ring current that encircles Earth behaves in a much different way than previously understood.[14] The ring current lies at approximately 10,000 to 60,000 kilometres (6,200 to 37,000 mi) from Earth. Electric current variations represent the dynamics of only the low-energy protons. The data indicates that there is a substantial, persistent ring current around the Earth even during non-storm times, which is carried by high-energy protons. During geomagnetic storms, the enhancement of the ring current is due to new, low-energy protons entering the near-Earth region.[14][15]

Scientific results

In February 2013, a third temporary Van Allen Radiation Belt was discovered by using data gathered by Van Allen Probes. The said third belt lasted a few weeks.[16]

Spacecraft

The Van Allen Probes consisted of two spin-stabilized spacecraft that were launched with a single Atlas V rocket. The two probes had to operate in the harsh conditions they were studying; while other satellites have the luxury of turning off or protecting themselves in the middle of intense space weather, the Van Allen Probes had to continue to collect data. The probes were, therefore, built to withstand the constant bombardment of particles and radiation they would experience in this intense area of space.[2]

Instruments

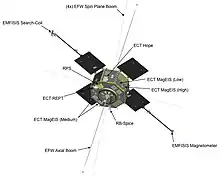

Because it was vital that the two craft make identical measurements to observe changes in the radiation belts through both space and time, each probe carried the following instruments:

- Energetic Particle, Composition, and Thermal Plasma (ECT) Instrument Suite;[17] The Principal Investigator is Harlan Spence from University of New Hampshire.[18] Key partners in this investigation are LANL, Southwest Research Institute, Aerospace Corporation and LASP

- Electric and Magnetic Field Instrument Suite and Integrated Science (EMFISIS);[19] The Principal Investigator is Craig Kletzing from the University of Iowa.

- Electric Field and Waves Instrument (EFW); The Principal Investigator is John Wygant from the University of Minnesota. Key partners in this investigation include the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Colorado at Boulder.

- Radiation Belt Storm Probes Ion Composition Experiment (RBSPICE); The Principal Investigator is Louis J. Lanzerotti from the New Jersey Institute of Technology. Key partners include the Applied Physics Laboratory and Fundamental Technologies, LLC.

- Relativistic Proton Spectrometer (RPS) from the National Reconnaissance Office

See also

- Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL)

- Cassini

- Cluster II (spacecraft)

- Heliophysics

- Solar Dynamics Observatory

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory

- STEREO (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory)

- TIMED (spacecraft)

- WIND (spacecraft)

References

- "Van Allen Probes: NASA Renames Radiation Belt Mission to Honor Pioneering Scientist". Science Daily. Reuters. 11 November 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- "RBSP - Mission Overview". NASA. 28 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP) Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "NASA's resilient van Allen Probes shut down – Spaceflight Now".

- Karen C. Fox (22 February 2011). "Launching Balloons in Antarctica". NASA. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses

- "Construction Begins!". The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. January 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012.

- "Probes launched". Space.com. 30 August 2012.

- "United Launch Alliance Atlas V Awarded Four NASA Rocket Launch Missions". ULA. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009.

- "Tropical Storm Isaac Delays NASA Launch". The Brevard Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Gebhardt, Chris (14 February 2019). "Beginning of the end: NASA's Van Allen probes prepare for mission's end". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Van Allen Probes Spacecraft B Completes Mission Operations". Applied Physics Laboratory. 23 July 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "Ten Highlights From NASA's Van Allen Probes Mission". NASA. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Cowing, Keith (19 May 2016). "Van Allen Probes Reveal Long-term Behavior of Earth's Ring Current". Space Ref. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Gkioulidou, Matina; et al. (19 May 2016). "Storm time dynamics of ring current protons: Implications for the long-term energy budget in the inner magnetosphere". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (10): 4736–4744. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.4736G. doi:10.1002/2016GL068013.

- "Ephemeral third ring of radiation makes appearance around Earth" Nature.com. Retrieved: 2 March 2013.

- "RBSP-ETC // About". Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- UNH, Kristi Donahue. "RBSP ECT team". rbsp-ect.sr.unh.edu. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Kletzing, C. A.; Kurth, W. S.; Acuna, M.; MacDowall, R. J.; Torbert, R. B.; Averkamp, T.; Bodet, D.; Bounds, S. R.; Chutter, M.; Connerney, J.; Crawford, D.; Dolan, J. S.; Dvorsky, R.; Hospodarsky, G. B.; Howard, J. (1 November 2013). "The Electric and Magnetic Field Instrument Suite and Integrated Science (EMFISIS) on RBSP". Space Science Reviews. 179 (1): 127–181. doi:10.1007/s11214-013-9993-6. ISSN 1572-9672.

External links

- Van Allen Probes website at NASA.gov

- Van Allen Probes website at Johns Hopkins University

- Van Allen Probes webpage Archived 20 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine at NASAtech.net