Rashtrakuta dynasty

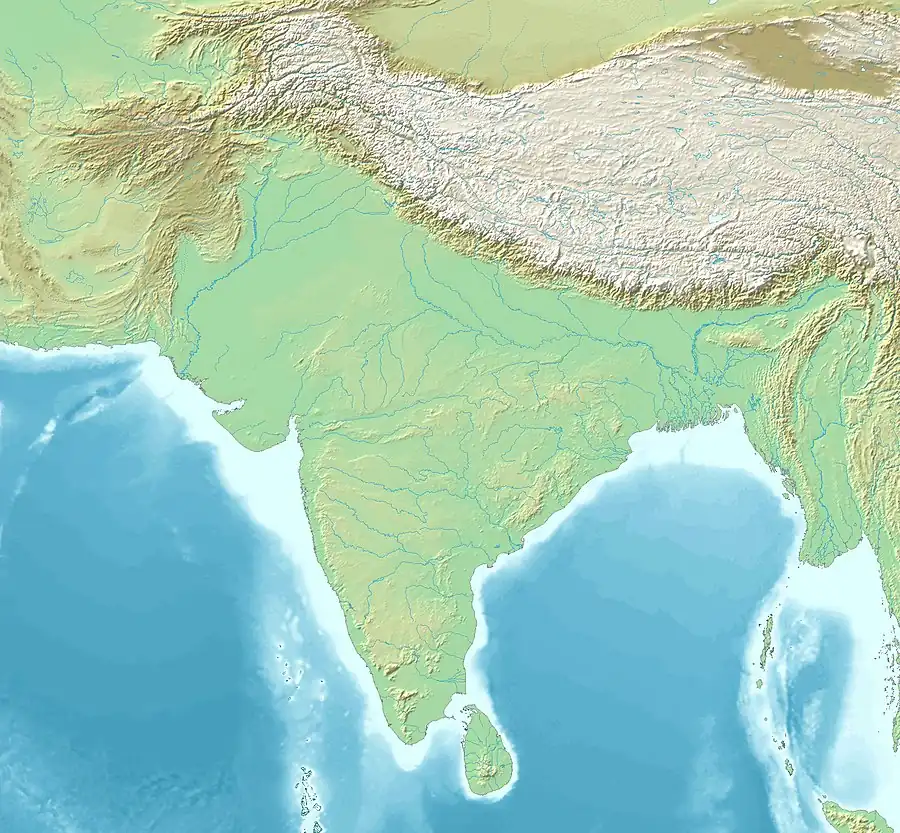

Rashtrakuta (IAST: rāṣṭrakūṭa) (r. 753 – 982 CE) was a royal Indian dynasty ruling large parts of the Indian subcontinent between the 6th and 10th centuries. The earliest known Rashtrakuta inscription is a 7th-century copper plate grant detailing their rule from Manapur, a city in Central or West India. Other ruling Rashtrakuta clans from the same period mentioned in inscriptions were the kings of Achalapur and the rulers of Kannauj. Several controversies exist regarding the origin of these early Rashtrakutas, their native homeland and their language.

Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 753 CE–982 CE | |||||||||

Core extent of Rashtrakuta Empire, 800 CE, 915 CE. [1] | |||||||||

| Status | Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Manyakheta | ||||||||

| Common languages | Kannada Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism Jainism Buddhism[2] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

• 735–756 | Dantidurga | ||||||||

• 973–982 | Indra IV | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Earliest Rashtrakuta records | 753 CE | ||||||||

• Established | 753 CE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 982 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

| Rashtrakuta dynasty |

|---|

|

The Elichpur clan was a feudatory of the Badami Chalukyas, and during the rule of Dantidurga, it overthrew Chalukya Kirtivarman II and went on to build an empire with the Gulbarga region in modern Karnataka as its base. This clan came to be known as the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta, rising to power in South India in 753 AD. At the same time the Pala dynasty of Bengal and the Prathihara dynasty of Malwa were gaining force in eastern and northwestern India respectively. An Arabic text, Silsilat al-Tawarikh (851), called the Rashtrakutas one of the four principal empires of the world.[3]

This period, between the 8th and the 10th centuries, saw a tripartite struggle for the resources of the rich Gangetic plains, each of these three empires annexing the seat of power at Kannauj for short periods of time. At their peak the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta ruled a vast empire stretching from the Ganges River and Yamuna River doab in the north to Kanyakumari in the south, a fruitful time of political expansion, architectural achievements and famous literary contributions. The early kings of this dynasty were influenced by Hinduism and the later kings by Jainism.

During their rule, Jain mathematicians and scholars contributed important works in Kannada and Sanskrit. Amoghavarsha I, the most famous king of this dynasty wrote Kavirajamarga, a landmark literary work in the Kannada language. Architecture reached a milestone in the Dravidian style, the finest example of which is seen in the Kailasanatha Temple at Ellora in modern Maharashtra. Other important contributions are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal in modern Karnataka, both of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

History

The origin of the Rashtrakuta dynasty has been a controversial topic of Indian history. These issues pertain to the origin of the earliest ancestors of the Rashtrakutas during the time of Emperor Ashoka in the 2nd century BCE,[4] and the connection between the several Rashtrakuta dynasties that ruled small kingdoms in northern and central India and the Deccan between the 6th and 7th centuries. The relationship of these medieval Rashtrakutas to the most famous later dynasty, the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta (present-day Malkhed in the Kalaburagi district, Karnataka state), who ruled between the 8th and 10th centuries has also been debated.[5][6][7]

The sources for Rashtrakuta history include medieval inscriptions, ancient literature in the Pali language,[8] contemporaneous literature in Sanskrit and Kannada and the notes of the Arab travellers.[9] Theories about the dynastic lineage (Surya Vamsa—Solar line and Chandra Vamsa—Lunar line), the native region and the ancestral home have been proposed, based on information gleaned from inscriptions, royal emblems, the ancient clan names such as "Rashtrika", epithets (Ratta, Rashtrakuta, Lattalura Puravaradhiswara), the names of princes and princesses of the dynasty, and clues from relics such as coins.[7][10] Scholars debate over which ethnic/linguistic groups can claim the early Rashtrakutas. Possibilities include the Kannadiga,[11][12][13][14] Reddi,[16] the Maratha,[17][18] the tribes from the Punjab region,[19] or other north western ethnic groups of India.[20]

Scholars however concur that the rulers of the imperial dynasty in the 8th to 10th century made the Kannada language as important as Sanskrit. Rashtrakuta inscriptions use both Kannada and Sanskrit (historians Sheldon Pollock and Jan Houben claim they are mostly in Kannada),[21][22][23][24][25] and the rulers encouraged literature in both languages. The earliest existing Kannada literary writings are credited to their court poets and royalty.[26][27][28][29] Though these Rashtrakutas were Kannadigas,[7][30][31][32][33][11] they were conversant in a northern Deccan language as well.[34]

The heart of the Rashtrakuta empire included nearly all of Karnataka, Maharashtra and parts of Andhra Pradesh, an area which the Rashtrakutas ruled for over two centuries. The Samangadh copper plate grant (753) confirms that the feudatory King Dantidurga, who probably ruled from Achalapura in Berar (modern Elichpur in Maharashtra), defeated the great Karnatic army (referring to the army of the Badami Chalukyas) of Kirtivarman II of Badami in 753 and took control of the northern regions of the Chalukya empire.[35][36][37] He then helped his son-in-law, Pallava King Nandivarman II regain Kanchi from the Chalukyas and defeated the Gurjaras of Malwa, and the rulers of Kalinga, Kosala and Srisailam.[38][39]

Dantidurga's successor Krishna I brought major portions of present-day Karnataka and Konkan under his control.[40][41] During the rule of Dhruva Dharavarsha who took control in 780, the kingdom expanded into an empire that encompassed all of the territory between the Kaveri River and Central India.[40][42][43][44] He led successful expeditions to Kannauj, the seat of northern Indian power where he defeated the Gurjara Pratiharas and the Palas of Bengal, gaining him fame and vast booty but not more territory. He also brought the Eastern Chalukyas and Gangas of Talakad under his control.[40][45] According to Altekar and Sen, the Rashtrakutas became a pan-India power during his rule.[44][46]

Expansion

The ascent of Dhruva Dharavarsha's third son, Govinda III, to the throne heralded an era of success like never before.[48] There is uncertainty about the location of the early capital of the Rashtrakutas at this time.[49][50][51] During his rule there was a three way conflict between the Rashtrakutas, the Palas and the Pratiharas for control over the Gangetic plains. Describing his victories over the Pratihara Emperor Nagabhatta II and the Pala Emperor Dharmapala,[40] the Sanjan inscription states the horses of Govinda III drank from the icy waters of the Himalayan streams and his war elephants tasted the sacred waters of the Ganges.[52][53] His military exploits have been compared to those of Alexander the Great and Arjuna of Mahabharata.[54] Having conquered Kannauj, he travelled south, took firm hold over Gujarat, Kosala (Kaushal), Gangavadi, humbled the Pallavas of Kanchi, installed a ruler of his choice in Vengi and received two statues as an act of submission from the king of Ceylon (one statue of the king and another of his minister). The Cholas, the Pandyas and the Kongu Cheras of Karur all paid him tribute.[55][56][57][58] As one historian puts it, the drums of the Deccan were heard from the Himalayan caves to the shores of the Malabar Coast.[54] The Rashtrakutas empire now spread over the areas from Cape Comorin to Kannauj and from Banaras to Bharuch.[59][60]

The successor of Govinda III, Amoghavarsha I made Manyakheta his capital and ruled a large empire. Manyakheta remained the Rashtrakutas' regal capital until the end of the empire.[61][62][63] He came to the throne in 814 but it was not until 821 that he had suppressed revolts from feudatories and ministers. Amoghavarsha I made peace with the Western Ganga dynasty by giving them his two daughters in marriage, and then defeated the invading Eastern Chalukyas at Vingavalli and assumed the title Viranarayana.[64][65] His rule was not as militant as that of Govinda III as he preferred to maintain friendly relations with his neighbours, the Gangas, the Eastern Chalukyas and the Pallavas with whom he also cultivated marital ties. His era was an enriching one for the arts, literature and religion. Widely seen as the most famous of the Rashtrakuta Emperors, Amoghavarsha I was an accomplished scholar in Kannada and Sanskrit.[66][67] His Kavirajamarga is considered an important landmark in Kannada poetics and Prashnottara Ratnamalika in Sanskrit is a writing of high merit and was later translated into the Tibetan language.[68] Because of his religious temperament, his interest in the arts and literature and his peace-loving nature, he has been compared to the emperor Ashoka and called "Ashoka of the South".[69]

During the rule of Krishna II, the empire faced a revolt from the Eastern Chalukyas and its size decreased to the area including most of the Western Deccan and Gujarat.[70] Krishna II ended the independent status of the Gujarat branch and brought it under direct control from Manyakheta. Indra III recovered the dynasty's fortunes in central India by defeating the Paramara and then invaded the doab region of the Ganges and Jamuna rivers. He also defeated the dynasty's traditional enemies, the Pratiharas and the Palas, while maintaining his influence over Vengi.[70][71][72] The effect of his victories in Kannauj lasted several years according to the 930 copper plate inscription of Emperor Govinda IV.[73][74] After a succession of weak kings during whose reigns the empire lost control of territories in the north and east, Krishna III the last great ruler consolidated the empire so that it stretched from the Narmada River to Kaveri River and included the northern Tamil country (Tondaimandalam) while levying tribute on the king of Ceylon.[75][76][77][78][79]

Decline

In 972 A.D.,[80] during the rule of Khottiga Amoghavarsha, the Paramara King Siyaka Harsha attacked the empire and plundered Manyakheta, the capital of the Rashtrakutas. This seriously undermined the reputation of the Rastrakuta Empire and consequently led to its downfall.[81] The final decline was sudden as Tailapa II, a feudatory of the Rashtrakuta ruling from Tardavadi province in modern Bijapur district, declared himself independent by taking advantage of this defeat.[82][83] Indra IV, the last emperor, committed Sallekhana (fasting unto death practised by Jain monks) at Shravanabelagola. With the fall of the Rashtrakutas, their feudatories and related clans in the Deccan and northern India declared independence. The Western Chalukyas annexed Manyakheta and made it their capital until 1015 and built an impressive empire in the Rashtrakuta heartland during the 11th century. The focus of dominance shifted to the Krishna River – Godavari River doab called Vengi. The former feudatories of the Rashtrakutas in western Deccan were brought under control of the Chalukyas, and the hitherto-suppressed Cholas of Tanjore became their arch enemies in the south.[84]

In conclusion, the rise of Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta had a great impact on India, even on India's north. Sulaiman (851), Al-Masudi (944) and Ibn Khurdadba (912) wrote that their empire was the largest in contemporary India and Sulaiman further called it one among the four great contemporary empires of the world.[85][86][87] According to the travelogues of the Arabs Al Masudi and Ibn Khordidbih of the 10th century, "most of the kings of Hindustan turned their faces towards the Rashtrakuta king while they were praying, and they prostrated themselves before his ambassadors. The Rashtrakuta king was known as the "King of kings" (Rajadhiraja) who possessed the mightiest of armies and whose domains extended from Konkan to Sind."[88] Some historians have called these times an "Age of Imperial Kannauj". Since the Rashtrakutas successfully captured Kannauj, levied tribute on its rulers and presented themselves as masters of North India, the era could also be called the "Age of Imperial Karnataka".[87] During their political expansion into central and northern India in the 8th to the 10th centuries, the Rashtrakutas or their relatives created several kingdoms that either ruled during the reign of the parent empire or continued to rule for centuries after its fall or came to power much later. Well known among these were the Rashtrakutas of Gujarat (757–888),[89] the Rattas of Saundatti (875–1230) in modern Karnataka,[90] the Gahadavalas of Kannauj (1068–1223),[91] the Rashtrakutas of Rajasthan (known as Rajputana) and ruling from Hastikundi or Hathundi (893–996),[92] Dahal (near Jabalpur),[93] Rathores of Mandore (near Jodhpur), the Rathores of Dhanop,[94] Rashtraudha dynasty of Mayuragiri in modern Maharashtra[95] and Rashtrakutas of Kannauj.[96] Rajadhiraja Chola's conquest of the island of Ceylon in the early 11th century CE led to the fall of four kings there. According to historian K. Pillay, one of them, King Madavarajah of the Jaffna kingdom, was an usurper from the Rashtrakuta Dynasty.[97]

Administration

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Karnataka |

|---|

|

Inscriptions and other literary records indicate the Rashtrakutas selected the crown prince based on heredity. The crown did not always pass on to the eldest son. Abilities were considered more important than age and chronology of birth, as exemplified by the crowning of Govinda III who was the third son of king Dhruva Dharavarsha. The most important position under the king was the Chief Minister (Mahasandhivigrahi) whose position came with five insignia commensurate with his position namely, a flag, a conch, a fan, a white umbrella, a large drum and five musical instruments called Panchamahashabdas. Under him was the commander (Dandanayaka), the foreign minister (Mahakshapataladhikrita) and a prime minister (Mahamatya or Purnamathya), all of whom were usually associated with one of the feudatory kings and must have held a position in government equivalent to a premier.[98] A Mahasamantha was a feudatory or higher ranking regal officer. All cabinet ministers were well versed in political science (Rajneeti) and possessed military training. There were cases where women supervised significant areas as when Revakanimaddi, daughter of Amoghavarsha I, administered Edathore Vishaya.

The kingdom was divided into Mandala or Rashtras (provinces). A Rashtra was ruled by a Rashtrapathi who on occasion was the emperor himself. Amoghavarsha I's empire had sixteen Rashtras. Under a Rashtra was a Vishaya (district) overseen by a Vishayapathi. Trusted ministers sometimes ruled more than a Rashtra. For example, Bankesha, a commander of Amoghavarsha I headed several Rashtras, besides ruling Banavasi which included 12,000 villages in that territory, lesser Rashtras included: Kunduru (500), Belvola (300), Puligere (300) and Kundarge (70). Below the Vishaya was the Nadu looked after by the Nadugowda (or Nadugavunda); sometimes there were two such officials, one assuming the position through heredity and another appointed centrally. The lowest division was a Grama or village administered by a Gramapathi or Prabhu Gavunda.[99]

The Rashtrakuta army consisted of large contingents of infantry, horsemen, and elephants. A standing army was always ready for war in a cantonment (Sthirabhuta Kataka) in the regal capital of Manyakheta. Large armies were also maintained by the feudatory kings who were expected to contribute to the defense of the empire in case of war. Chieftains and all the officials also served as commanders whose postings were transferable if the need arose.[100]

The Rashtrakutas issued coins (minted in an Akkashale) such as Suvarna, Drammas in silver and gold weighing 65 grains, Kalanju weighing 48 grains, Gadyanaka weighing 96 grains, Kasu weighing 15 grains, Manjati with 2.5 grains and Akkam of 1.25 grain.[101]

Economy

The Rashtrakuta economy was sustained by its natural and agricultural produce, its manufacturing revenues and moneys gained from its conquests. Cotton was the chief crop of the regions of southern Gujarat, Khandesh and Berar. Minnagar, Gujarat, Ujjain, Paithan and Tagara were important centres of textile industry. Muslin cloth were manufactured in Paithan and Warangal. The cotton yarn and cloth was exported from Bharoch. White calicos were manufactured in Burhanpur and Berar and exported to Persia, Byzantines, Khazaria, Arabia and Egypt.[102] The Konkan region, ruled by the feudatory Silharas, produced large quantities of betel leaves, coconut and rice while the lush forests of Mysore, ruled by the feudatory Gangas, produced such woods as sandal, timber, teak and ebony. Incense and perfumes were exported from the ports of Thana and Saimur.[103]

The Deccan was rich in minerals, though its soil was not as fertile as that of the Gangetic plains. The copper mines of Cudappah, Bellary, Chanda, Buldhana, Narsingpur, Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Dharwar were an important source of income and played an important role in the economy.[104] Diamonds were mined in Cudappah, Bellary, Kurnool and Golconda; the capital Manyakheta and Devagiri were important diamond and jewellery trading centres. The leather industry and tanning flourished in Gujarat and some regions of northern Maharashtra. Mysore with its vast elephant herds was important for the ivory industry.[105]

The Rashtrakuta empire controlled most of the western sea board of the subcontinent which facilitated its maritime trade.[103] The Gujarat branch of the empire earned a significant income from the port of Bharoch, one of the most prominent ports in the world at that time.[106] The empire's chief exports were cotton yarn, cotton cloth, muslins, hides, mats, indigo, incense, perfumes, betel nuts, coconuts, sandal, teak, timber, sesame oil and ivory. Its major imports were pearls, gold, dates from Arabia, slaves, Italian wines, tin, lead, topaz, storax, sweet clover, flint glass, antimony, gold and silver coins, singing boys and girls (for the entertainment of the royalty) from other lands. Trading in horses was an important and profitable business, monopolised by the Arabs and some local merchants.[107] The Rashtrakuta government levied a shipping tax of one golden Gadyanaka on all foreign vessels embarking to any other ports and a fee of one silver Ctharna ( a coin) on vessels travelling locally.[108]

Artists and craftsman operated as corporations (guilds) rather than as individual business. Inscriptions mention guilds of weavers, oilmen, artisans, basket and mat makers and fruit sellers. A Saundatti inscription refers to an assemblage of all the people of a district headed by the guilds of the region.[109] Some guilds were considered superior to others, just as some corporations were, and received royal charters determining their powers and privileges. Inscriptions suggest these guilds had their own militia to protect goods in transit and, like village assemblies, they operated banks that lent money to traders and businesses.[110]

The government's income came from five principal sources: regular taxes, occasional taxes, fines, income taxes, miscellaneous taxes and tributes from feudatories.[111] An emergency tax was imposed occasionally and were applicable when the kingdom was under duress, such as when it faced natural calamities, or was preparing for war or overcoming war's ravages. Income tax included taxes on crown land, wasteland, specific types of trees considered valuable to the economy, mines, salt, treasures unearthed by prospectors.[112] Additionally, customary presents were given to the king or royal officers on such festive occasions as marriage or the birth of a son.[113]

The king determined the tax levels based on need and circumstances in the kingdom while ensuring that an undue burden was not placed on the peasants.[114] The land owner or tenant paid a variety of taxes, including land taxes, produce taxes and payment of the overhead for maintenance of the Gavunda (village head). Land taxes were varied, based on type of land, its produce and situation and ranged from 8% to 16%. A Banavasi inscription of 941 mentions reassessment of land tax due to the drying up of an old irrigation canal in the region.[115] The land tax may have been as high as 20% to pay for expenses of a military frequently at war.[116] In most of the kingdom, land taxes were paid in goods and services and rarely was cash accepted.[117] A portion of all taxes earned by the government (usually 15%) was returned to the villages for maintenance.[115]

Taxes were levied on artisans such as potters, sheep herders, weavers, oilmen, shopkeepers, stall owners, brewers and gardeners. Taxes on perishable items such as fish, meat, honey, medicine, fruits and essentials like fuel was as high as 16%.[108] Taxes on salt and minerals were mandatory although the empire did not claim sole ownership of mines, implying that private mineral prospecting and the quarrying business may have been active.[118] The state claimed all such properties whose deceased legal owner had no immediate family to make an inheritance claim.[119] Other miscellaneous taxes included ferry and house taxes. Only Brahmins and their temple institutions were taxed at a lower rate.[120]

Culture

Religion

The Rashtrakuta kings supported the popular religions of the day in the traditional spirit of religious tolerance.[121] Scholars have offered various arguments regarding which specific religion the Rashtrakutas favoured, basing their evidence on inscriptions, coins and contemporary literature. Some claim the Rashtrakutas were inclined towards Jainism since many of the scholars who flourished in their courts and wrote in Sanskrit, Kannada and a few in Apabhramsha and Prakrit were Jains.[122] The Rashtrakutas built well-known Jain temples at locations such as Lokapura in Bagalkot district and their loyal feudatory, the Western Ganga Dynasty, built Jain monuments at Shravanabelagola and Kambadahalli. Scholars have suggested that Jainism was a principal religion at the very heart of the empire, modern Karnataka, accounting for more than 30% of the population and dominating the culture of the region.[123] King Amoghavarsha I was a disciple of the Jain acharya Jinasena and wrote in his religious writing, Prashnottara Ratnamalika, "having bowed to Varaddhamana (Mahavira), I write Prashnottara Ratnamalika". The mathematician Mahaviracharya wrote in his Ganita Sarasangraha, "The subjects under Amoghavarsha are happy and the land yields plenty of grain. May the kingdom of King Nripatunga Amoghavarsha, follower of Jainism ever increase far and wide." Amoghavarsha may have taken up Jainism in his old age.[124][125]

However, the Rashtrakuta kings also patronized Hinduism's followers of the Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta faiths. Almost all of their inscriptions begin with an invocation to god Vishnu or god Shiva. The Sanjan inscriptions tell of King Amoghavarsha I sacrificing a finger from his left hand at the Lakshmi temple at Kolhapur to avert a calamity in his kingdom. King Dantidurga performed the Hiranyagarbha (horse sacrifice) and the Sanjan and Cambay plates of King Govinda IV mention Brahmins performing such rituals as Rajasuya, Vajapeya and Agnishtoma.[126] An early copper plate grant of King Dantidurga (753) shows an image of god Shiva and the coins of his successor, King Krishna I (768), bear the legend Parama Maheshwara (another name for Shiva). The kings' titles such as Veeranarayana showed their Vaishnava leanings. Their flag had the sign of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, perhaps copied from the Badami Chalukyas.[127] The famous Kailasnatha temple at Ellora and other rock-cut caves attributed to them show that the Hinduism was flourishing.[126] Their family deity was a goddess by name Latana (also known as Rashtrashyena, Manasa Vindyavasini) who took the form of a falcon to save the kingdom.[128] They built temples with icons and ornamentation that satisfied the needs of different faiths. The temple at Salotgi was meant for followers of Shiva and Vishnu and the temple at Kargudri was meant for worshipers of Shiva, Vishnu and Bhaskara (Surya, the sun god).[122]

In short, the Rashtrakuta rule was tolerant to multiple popular religions, Jainism, Vaishnavaism and Shaivism. Buddhism too found support and was popular in places such as Dambal and Balligavi, although it had declined significantly by this time.[2] The decline of Buddhism in South India began in the 8th century with the spread of Adi Shankara's Advaita philosophy.[129] Islamic contact with South India began as early as the 7th century, a result of trade between the Southern kingdoms and Arab lands. Jumma Masjids existed in the Rashtrakuta empire by the 10th century[130] and many Muslims lived and mosques flourished on the coasts, specifically in towns such as Kayalpattanam and Nagore. Muslim settlers married local women; their children were known as Mappilas (Moplahs) and were actively involved in horse trading and manning shipping fleets.[131]

Society

Chronicles mention more castes than the four commonly known castes in the Hindu social system, some as many as seven castes.[132] Al-Biruni, the famed 10th century Persian / central Asian Indologist mentions sixteen castes including the four basic castes of Brahmins, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Sudras.[133] The Zakaya or Lahud caste consisted of communities specialising in dance and acrobatics.[134] People in the professions of sailing, hunting, weaving, cobblery, basket making and fishing belonged to specific castes or subcastes. The Antyajas caste provided many menial services to the wealthy. Brahmins enjoyed the highest status in Rashtrakuta society; only those Kshatriyas in the Sat-Kshatriya sub-caste (noble Kshatriyas) were higher in status.[135][136]

The careers of Brahmins usually related to education, the judiciary, astrology, mathematics, poetry and philosophy[137] or the occupation of hereditary administrative posts.[138] Also Brahmins increasingly practiced non-Brahminical professions (agriculture, trade in betel nuts and martial posts).[139] Capital punishment, although widespread, was not given to the royal Kshatriya sub-castes or to Brahmins found guilty of heinous crimes (as the killing of a Brahmin in medieval Hindu India was itself considered a heinous crime). As an alternate punishment to enforce the law a Brahmin's right hand and left foot was severed, leaving that person disabled.[140]

By the 9th century, kings from all the four castes had occupied the highest seat in the monarchical system in Hindu India.[141] Admitting Kshatriyas to Vedic schools along with Brahmins was customary, but the children of the Vaishya and Shudra castes were not allowed. Landownership by people of all castes is recorded in inscriptions[142] Intercaste marriages in the higher castes were only between highly placed Kshatriya girls and Brahmin boys,[143] but was relatively frequent among other castes.[144] Intercaste functions were rare and dining together between people of various castes was avoided.[145]

Joint families were the norm but legal separations between brothers and even father and son have been recorded in inscriptions.[146] Women and daughters had rights over property and land as there are inscriptions recording the sale of land by women.[147] The arranged marriage system followed a strict policy of early marriage for women. Among Brahmins, boys married at or below 16 years of age and the brides chosen for them were 12 or younger. This age policy was not strictly followed by other castes.[148] Sati (a custom in which a dead man's widow would immolate herself on her husband's funeral pyre) was practiced but the few examples noted in inscriptions were mostly in the royal families.[149] The system of shaving the heads of widows was infrequent as epigraphs note that widows were allowed to grow their hair but decorating it was discouraged.[150] The remarriage of a widow was rare among the upper castes and more accepted among the lower castes.[151]

In the general population men wore two simple pieces of cloth, a loose garment on top and a garment worn like a dhoti for the lower part of the body. Only kings could wear turbans, a practice that spread to the masses much later.[152] Dancing was a popular entertainment and inscriptions speak of royal women being charmed by dancers, both male and female, in the king's palace. Devadasis (girls were "married" to a deity or temple) were often present in temples.[153] Other recreational activities included attending animal fights of the same or different species. The Atakur inscription (hero stone, virgal) was made for the favourite hound of the feudatory Western Ganga King Butuga II that died fighting a wild boar in a hunt.[154] There are records of game preserves for hunting by royalty. Astronomy and astrology were well developed as subjects of study,[154] and there were many superstitious beliefs such as catching a snake alive proved a woman's chastity. Old persons suffering from incurable diseases preferred to end their lives by drowning in the sacred waters of a pilgrim site or by a ritual burning.[155]

Literature

Kannada became more prominent as a literary language during the Rashtrakuta rule with its script and literature showing remarkable growth, dignity and productivity.[24][27][29] This period effectively marked the end of the classical Prakrit and Sanskrit era. Court poets and royalty created eminent works in Kannada and Sanskrit that spanned such literary forms as prose, poetry, rhetoric, the Hindu epics and the life history of Jain tirthankars. Bilingual writers such as Asaga gained fame,[156] and noted scholars such as the Mahaviracharya wrote on pure mathematics in the court of King Amoghavarsha I.[157][158]

Kavirajamarga (850) by King Amoghavarsha I is the earliest available book on rhetoric and poetics in Kannada,[67][68] though it is evident from this book that native styles of Kannada composition had already existed in previous centuries.[159] Kavirajamarga is a guide to poets (Kavishiksha) that aims to standardize these various styles. The book refers to early Kannada prose and poetry writers such as Durvinita, perhaps the 6th-century monarch of Western Ganga Dynasty.[160][161][162]

The Jain writer Adikavi Pampa, widely regarded as one of the most influential Kannada writers, became famous for Adipurana (941). Written in champu (mixed prose-verse style) style, it is the life history of the first Jain tirthankara Rishabhadeva. Pampa's other notable work was Vikramarjuna Vijaya (941), the author's version of the Hindu epic, Mahabharata, with Arjuna as the hero.[163] Also called Pampa Bharata, it is a eulogy of the writer's patron, King Chalukya Arikeseri of Vemulawada (a Rashtrakuta feudatory), comparing the king's virtues favorably to those of Arjuna. Pampa demonstrates such a command of classical Kannada that scholars over the centuries have written many interpretations of his work.[164]

Another notable Jain writer in Kannada was Sri Ponna, patronised by King Krishna III and famed for Shantipurana, his account of the life of Shantinatha, the 16th Jain tirthankara. He earned the title Ubhaya Kavichakravathi (supreme poet in two languages) for his command over both Kannada and Sanskrit. His other writings in Kannada were Bhuvanaika-ramaabhyudaya, Jinaksharamale and Gatapratyagata.[67][165] Adikavi Pampa and Sri Ponna are called "gems of Kannada literature".[163]

Prose works in Sanskrit was prolific during this era as well.[27] Important mathematical theories and axioms were postulated by Mahaviracharya, a native of Gulbarga, who belonged to the Karnataka mathematical tradition and was patronised by King Amoghavarsha I.[157] His greatest contribution was Ganitasarasangraha, a writing in 9 chapters. Somadevasuri of 950 wrote in the court of Arikesari II, a feudatory of Rashtrakuta Krishna III in Vemulavada. He was the author of Yasastilaka champu, Nitivakyamrita and other writings. The main aim of the champu writing was to propagate Jain tenets and ethics. The second writing reviews the subject matter of Arthashastra from the standpoint of Jain morals in a clear and pithy manner.[166] Ugraditya, a Jain ascetic from Hanasoge in the modern Mysore district wrote a medical treatise called Kalyanakaraka. He delivered a discourse in the court of Amoghavarsha I encouraging abstinence from animal products and alcohol in medicine.[167][168]

Trivikrama was a noted scholar in the court of King Indra III. His classics were Nalachampu (915), the earliest in champu style in Sanskrit, Damayanti Katha, Madalasachampu and Begumra plates. Legend has it that Goddess Saraswati helped him in his effort to compete with a rival in the king's court.[166] Jinasena was the spiritual preceptor and guru of Amoghavarsha I. A theologian, his contributions are Dhavala and Jayadhavala (written with another theologian Virasena). These writings are named after their patron king who was also called Athishayadhavala. Other contributions from Jinasena were Adipurana, later completed by his disciple Gunabhadra, Harivamsha and Parshvabhyudaya.[157]

Architecture

The Rashtrakutas contributed much to the architectural heritage of the Deccan. Art historian Adam Hardy categorizes their building activity into three schools: Ellora, around Badami, Aihole and Pattadakal, and at Sirval near Gulbarga.[169] The Rashtrakuta contributions to art and architecture are reflected in the splendid rock-cut cave temples at Ellora and Elephanta, areas also occupied by Jain monks, located in present-day Maharashtra. The Ellora site was originally part of a complex of 34 Buddhist caves probably created in the first half of the 6th century whose structural details show Pandyan influence. Cave temples occupied by Hindus are from later periods.[170]

The Rashtrakutas renovated these Buddhist caves and re-dedicated the rock-cut shrines. Amoghavarsha I espoused Jainism and there are five Jain cave temples at Ellora ascribed to his period.[171] The most extensive and sumptuous of the Rashtrakuta works at Ellora is their creation of the monolithic Kailasanath Temple, a splendid achievement confirming the "Balhara" status as "one among the four principal Kings of the world".[86] The walls of the temple have marvellous sculptures from Hindu mythology including Ravana, Shiva and Parvathi while the ceilings have paintings.

The Kailasanath Temple project was commissioned by King Krishna I after the Rashtrakuta rule had spread into South India from the Deccan. The architectural style used is Karnata Dravida according to Adam Hardy. It does not contain any of the Shikharas common to the Nagara style and was built on the same lines as the Virupaksha temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka.[172][173] According to art historian Vincent Smith, the achievement at the Kailasanath temple is considered an architectural consummation of the monolithic rock-cut temple and deserves to be considered one of the wonders of the world.[174] According to art historian Percy Brown, as an accomplishment of art, the Kailasanath temple is considered an unrivalled work of rock architecture, a monument that has always excited and astonished travellers.[175]

While some scholars have claimed the architecture at Elephanta is attributable to the Kalachuri, others claim that it was built during the Rashtrakuta period.[176] Some of the sculptures such as Nataraja and Sadashiva excel in beauty and craftsmanship even that of the Ellora sculptures.[177] Famous sculptures at Elephanta include Ardhanarishvara and Maheshamurthy. The latter, a three faced bust of Lord Shiva, is 25 feet (8 m) tall and considered one of the finest pieces of sculpture in India. It is said that, in the world of sculpture, few works of art depicting a divinity are as balanced.[178]

In Karnataka their most famous temples are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal, a UNESCO World Heritage site.[179][180] Other well-known temples are the Parameshwara temple at Konnur, Brahmadeva temple at Savadi, the Settavva, Kontigudi II, Jadaragudi and Ambigeragudi temples at Aihole, Mallikarjuna temple at Ron, Andhakeshwara temple at Huli (Hooli), Someshwara temple at Sogal, Jain temples at Lokapura, Navalinga temple at Kuknur, Kumaraswamy temple at Sandur, numerous temples at Shirival in Gulbarga,[181] and the Trikuteshwara temple at Gadag which was later expanded by Kalyani Chalukyas. Archeological study of these temples show some have the stellar (multigonal) plan later to be used profusely by the Hoysalas at Belur and Halebidu.[182] One of the richest traditions in Indian architecture took shape in the Deccan during this time which Adam Hardy calls Karnata dravida style as opposed to traditional Dravida style.[183]

Language

With the ending of the Gupta Dynasty in northern India in the early 6th century, major changes began taking place in the Deccan south of the Vindyas and in the southern regions of India. These changes were not only political but also linguistic and cultural. The royal courts of peninsular India (outside of Tamilakam) interfaced between the increasing use of the local Kannada language and the expanding Sanskritic culture. Inscriptions, including those that were bilingual, demonstrate the use of Kannada as the primary administrative language in conjunction with Sanskrit.[22][23] Government archives used Kannada for recording pragmatic information relating to grants of land.[184] The local language formed the desi (popular) literature while literature in Sanskrit was more marga (formal). Educational institutions and places of higher learning (ghatikas) taught in Sanskrit, the language of the learned Brahmins, while Kannada increasingly became the speech of personal expression of devotional closeness of a worshipper to a private deity. The patronage Kannada received from rich and literate Jains eventually led to its use in the devotional movements of later centuries.[185]

Contemporaneous literature and inscriptions show that Kannada was not only popular in the modern Karnataka region but had spread further north into present day southern Maharashtra and to the northern Deccan by the 8th century.[186] Kavirajamarga, the work on poetics, refers to the entire region between the Kaveri River and the Godavari River as "Kannada country".[187][188][189] Higher education in Sanskrit included the subjects of Veda, Vyakarana (grammar), Jyotisha (astronomy and astrology), Sahitya (literature), Mimansa (Exegesis), Dharmashastra (law), Puranas (ritual), and Nyaya (logic). An examination of inscriptions from this period shows that the Kavya (classical) style of writing was popular. The awareness of the merits and defects in inscriptions by the archivists indicates that even they, though mediocre poets, had studied standard classical literature in Sanskrit.[190] An inscription in Kannada by King Krishna III, written in a poetic Kanda metre, has been found as far away as Jabalpur in modern Madhya Pradesh.[21] Kavirajamarga, a work on poetics in Kannada by Amoghavarsha I, shows that the study of poetry was popular in the Deccan during this time. Trivikrama's Sanskrit writing, Nalachampu, is perhaps the earliest in the champu style from the Deccan.[191]

- Kailasa temple, Ellora

Interior and arcades

Interior and arcades

Shikhara of Indra Sabha at Ellora.

Shikhara of Indra Sabha at Ellora.

Notes

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (h). ISBN 0226742210.

- The Rise and Decline of Buddhism in India, K.L. Hazara, Munshiram Manoharlal, 1995, pp288–294

- Reu (1933), p39

- Reu (1933), pp1–5

- Altekar (1934), pp1–32

- Reu (1933), pp6–9, pp47–53

- Kamath (2001), p72–74

- Reu (1933), p1

- Kamath (2001), p72

- Reu (1933), pp1–15

- Anirudh Kanisetti (2022). Lords of the Deccan: Southern India from the Chalukyas to the Cholas. India: Juggernaut. p. 193. ISBN 978-93-91165-0-55.

It is most likely that they were Kannada-speaking military aristocrats settled at a strategic point in modern-day Maharasthra by the Chalukyas or some other powerful group, perhaps to keep an eye on trade routes and various tribal peoples.

- A Kannada dynasty was created in Berar under the rule of Badami Chalukyas (Altekar 1934, p21–26)

- Kamath 2001, p72–3

- Singh (2008), p556

- A.C. Burnell in Pandit Reu (1933), p4

- C.V. Vaidya (1924), p171

- D.R.Bhandarkar in Reu, (1933), p1, p7

- Hultzsch and Reu in Reu (1933), p2, p4

- J. F. Fleet in Reu (1933), p6

- Kamath (2001), p73

- Pollock 2006, p332

- Houben(1996), p215

- Altekar (1934), p411–3

- Dalby (1998), p300

- Sen (1999), pp380-381

- During the rule of the Rashtrakutas, literature in Kannada and Sanskrit flowered (Kamath 2001, pp 88–90)

- Even royalty of the empire took part in poetic and literary activities – Thapar (2003), p334

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp17–18, p68

- Altekar (1934), pp21–24

- Possibly Dravidian Kannada origin (Karmarkar 1947 p26)

- Masica (1991), p45-46

- Rashtrakutas are described as Kannadigas from Lattaluru who encouraged the Kannada language (Chopra, Ravindran, Subrahmanian 2003, p87)

- Hoiberg and Ramchandani (2000). Rashtrakuta Dynasty. Students Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- Reu (1933), p54

- From Rashtrakuta inscriptions call the Badami Chalukya army Karnatabala (power of Karnata) (Kamath 2001, p57, p65)

- Altekar in Kamath (2001), p72

- Sastri (1955), p141

- Thapar (2003), p333

- Sastri (1955), p143

- Sen (1999), p368

- Desai and Aiyar in Kamath (2001), p75

- Reu (1933), p62

- Sen (1999), p370

- The Rashtrakutas interfered effectively in the politics of Kannauj (Thapar 2003), p333

- From the Karda inscription, a digvijaya (Altekar in Kamath 2001, p75)

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 31, 146. ISBN 0226742210.

- The ablest of the Rashtrakuta kings (Altekar in Kamath 2001, p77)

- Modern Morkhandi (Mayurkhandi in Bidar district (Kamath 2001, p76)

- modern Morkhand in Maharashtra (Reu 1933, p65)

- Sooloobunjun near Ellora (Couseris in Altekar 1934, p48). Perhaps Elichpur remained the capital until Amoghavarsha I built Manyakheta. From the Wani-Dmdori, Radhanpur and Kadba plates, Morkhand in Maharashtra was only a military encampment, from the Dhulia and Pimpen plates it seems Nasik was only a seat of a viceroy, and the Paithan plates of Govinda III indicate that neither Latur nor Paithan was the early capital.(Altekar, 1934, pp47–48)

- Kamath 2001, MCC, p76

- From the Sanjan inscriptions, Dr. Jyotsna Kamat. "The Rashrakutas". 1996–2006 Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Keay (2000), p199

- From the Nesari records (Kamath 2001, p76)

- Reu (1933), p65

- Sastri (1955), p144

- Narayanan, M. G. S. (2013), p95, Perumāḷs of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy: Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cēra Perumāḷs of Makōtai (c. AD 800 – AD 1124). Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks

- "The victorious march of his armies had literally embraced all the territory between the Himalayas and Cape Comorin" (Altekar in Kamath 2001, p77)

- Sen (1999), p371

- Which could put to shame even the capital of gods-From Karda plates (Altekar 1934, p47)

- A capital city built to excel that of Indra (Sastri, 1955, p4, p132, p146)

- Reu 1933, p71

- from the Cambay and Sangli records. The Bagumra record claims that Amoghavarsha saved the "Ratta" kingdom which was drowned in an "ocean of Chalukyas" (Kamath 2001, p78)

- Sastri (1955), p145

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p1

- Kamath (2001), p90

- Reu (1933), p38

- Panchamukhi in Kamath (2001), p80

- Sastri (1955), p161

- From the writings of Adikavi Pampa (Kamath 2001, p81)

- Sen (1999), pp373-374

- Kamath (2001), p82

- The Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta gained control over Kannauj for a brief period during the early 10th century (Thapar 2003, p333)

- From the Siddalingamadam record of 944 – Krishna III captured Kanchi and Tanjore as well and had full control over northern Tamil regions (Aiyer in Kamath 2001, pp82–83)

- From the Tirukkalukkunram inscription – Kanchi and Tanjore were annexed by Krishna III. From the Deoli inscription – Krishna III had feudatories from Himalayas to Ceylon. From the Laksmeshwar inscription – Krishna III was an incarnation of death for the Chola Dynasty (Reu 1933, p83)

- Conqueror of Kanchi, (Thapar 2003, p334)

- Conqueror of Kanchi and Tanjore (Sastri 1955, p162)

- Sen 1999), pp374-375

- Chandra, Satish (2009). History of Medieval India. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Private Limited. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7.

- "Amoghavarsha IV". 2007 Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- The province of Tardavadi in the very heart of the Rashtrakuta empire was given to Tailapa II as a fief (provincial grant) by Rashtrakuta Krishna III for services rendered in war (Sastri 1955, p162)

- Kamath (2001), p101

- Kamath (2001), pp100–103

- Reu (1933), p39–41

- Keay (2000), p200

- Kamath (2001), p94

- Burjor Avari (2007), India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200, pp.207–208, Routledge, New York, ISBN 978-0-415-35615-2

- Reu (1933), p93

- Reu (1933), p100

- Reu (1933), p113

- Reu (1933), p110

- Jain (2001), pp67–75

- Reu (1933), p112

- De Bruyne (1968)

- Majumdar (1966), pp50–51

- Pillay, K. (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. OCLC 250247191.

- whose main responsibility was to draft and maintain inscriptions or Shasanas as would an archivist. (Altekar in Kamath (2001), p85

- Kamath (2001), p86

- From the notes of Al Masudi (Kamath 2001, p88)

- Kamath (2001), p88

- Altekar (1934), p356

- Altekar (1934), p354

- Altekar (1934), p355

- From notes of Periplus, Al Idrisi and Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p357)

- Altekar (1934), p358

- Altekar (1934), p358–359

- Altekar (1934), p230

- Altekar (1934), p368

- Altekar (1934), p370–371

- Altekar (1934), p223

- Altekar (1934), p213

- From the Davangere inscription of Santivarma of Banavasi-12000 province (Altekar 1934, p234

- From the writings of Chandesvara (Altekar 1934, p216)

- Altekar (1934), p222

- From the notes of Al Idrisi (Altekar (1934), p223

- From the Begumra plates of Krishna II (Altekar 1934, p227

- Altekar (1934), p242

- From the writings of Somadeva (Altekar 1934, p244)

- From the Hebbal inscriptions and Torkhede inscriptions of Govinda III (Altekar 1934, p232

- "Wide and sympathetic tolerance" in general characterised the Rashtrakuta rule (Altekar in Kamath 2001, p92)

- Kamath (2001), p92

- Altekar in Kamath (2001), p92

- Reu (1933), p36

- The Vaishnava Rashtrakutas patronised Jainism (Kamath 2001, p92)

- Kamath (2001), p91

- Reu (1933), p34

- Reu (1933, p34

- A 16th-century Buddhist work by Lama Taranatha speaks disparagingly of Shankaracharya as close parallels in some beliefs of Shankaracharya with Buddhist philosophy was not viewed favourably by Buddhist writers (Thapar 2003, pp 349–350, 397)

- From the notes of 10th-century Arab writer Al-Ishtakhri (Sastri 1955, p396)

- From the notes of Masudi (916) (Sastri 1955, p396)

- From the notes of Magasthenesis and Strabo from Greece and Ibn Khurdadba and Al Idrisi from Arabia (Altekar 1934, p317)

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p317)

- Altekar (1934), p318

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p324)

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, pp330–331)

- From the notes of Alberuni, Altekar (1934) p325

- From the notes of Abuzaid (Altekar 1934, p325)

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p326)

- Altekar (1934), p329

- From the notes of Yuan Chwang, Altekar (1934), p331

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p332, p334)

- From the notes of Ibn Khurdadba (Altekar 1934, p337)

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p337)

- From the notes of Al Masudi and Al Idrisi (Altekar 1934, p339)

- From the Tarkhede inscription of Govinda III, (Altekar 1934, p339)

- Altekar (1934), p341

- From the notes of Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p342)

- From the notes of Sulaiman and Alberuni (Altekar 1934, p343)

- Altekar (1934), p345

- From the notes of Ibn Khurdadba (Altekar 1934, p346)

- Altekar (1934), p349

- Altekar (1934), p350

- Altekar (1934), p351

- From the notes of Ibn Kurdadba (Altekar 1934, p353)

- Warder A.K. (1988), p. 248

- Kamath (2001), p89

- "Mathematical Achievements of Pre-modern Indian Mathematicians", Putta Swamy T.K., 2012, chapter=Mahavira, p.231, Elsevier Publications, London, ISBN 978-0-12-397913-1

- The Bedande and Chattana type of composition (Narasimhacharya 1988, p12)

- It is said Kavirajamarga may have been co-authored by Amoghavarsha I and court poet Sri Vijaya (Sastri 1955, pp355–356)

- Other early writers mentioned in Kavirajamarga are Vimala, Udaya, Nagarjuna, Jayabhandu for Kannada prose and Kavisvara, Pandita, Chandra and Lokapala in Kannada poetry (Narasimhacharya 1988, p2)

- Warder A.K. (1988), p240

- Sastri (1955), p356

- L.S. Seshagiri Rao in Amaresh Datta (1988), p1180

- Narasimhacharya (1988, p18

- Sastri (1955), p314

- S.K. Ramachandra Rao, (1985), Encyclopedia of Indian Medicine: Historical perspective, pp100-101, Popular Prakashan, Mumbai, ISBN 81-7154-255-7

- Narasimhachar (1988), p11

- Hardy (1995), p111

- Rajan, K.V. Soundara (1998). Rock-cut Temple Styles'. Mumbai, India: Somaily Publications. pp. 19, 115–116. ISBN 81-7039-218-7.

- Takeo Kamiya. "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent". Gerard da Cunha-Architecture Autonomous, India. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- Takeo Kamiya. "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent,20 September 1996". Gerard da Cunha-Architecture Autonomous, Bardez, Goa, India. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- Hardy (1995), p327

- Vincent Smith in Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Percy Brown and James Fergusson in Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Kamath (2001), p93

- Arthikaje in Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Grousset in Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Vijapur, Raju S. "Reclaiming past glory". Deccan Herald. Spectrum. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Hardy (1995), p.341

- Hardy (1995), p344-345

- Sundara and Rajashekar, Arthikaje, Mangalore. "Society, Religion and Economic condition in the period of Rashtrakutas". 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- Hardy (1995), p5 (introduction)

- Thapar (2002), pp393–4

- Thapar (2002), p396

- Vaidya (1924), p170

- Sastri (1955), p355

- Rice, E.P. (1921), p12

- Rice, B.L. (1897), p497

- Altekar (1934), p404

- Altekar (1934), p408

References

Books

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1934) [1934]. The Rashtrakutas And Their Times; being a political, administrative, religious, social, economic and literary history of the Deccan during C. 750 A.D. to C. 1000 A.D. Poona: Oriental Book Agency. OCLC 3793499.

- Chopra, P.N.; Ravindran, T.K.; Subrahmanian, N (2003) [2003]. History of South India (Ancient, Medieval and Modern) Part 1. New Delhi: Chand Publications. ISBN 81-219-0153-7.

- De Bruyne, J.L. (1968) [1968]. Rudrakavis Great Poem of the Dynasty of Rastraudha. EJ Brill.

- Dalby, Andrew (2004) [1998]. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11569-5.

- Hardy, Adam (1995) [1995]. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation-The Karnata Dravida Tradition 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-312-4.

- Houben, Jan E.M. (1996) [1996]. Ideology and Status of Sanskrit: Contributions to the History of the Sanskrit language. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10613-8.

- Jain, K.C. (2001) [2001]. Bharatiya Digambar Jain Abhilekh. Madhya Pradesh: Digambar Jain Sahitya Samrakshan Samiti.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A concise history of Karnataka : from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.

- Karmarkar, A.P. (1947) [1947]. Cultural history of Karnataka : ancient and medieval. Dharwar: Karnataka Vidyavardhaka Sangha. OCLC 8221605.

- Keay, John (2000) [2000]. India: A History. New York: Grove Publications. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Majumdar, R.C. (1966) [1966]. The Struggle for Empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991) [1991]. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29944-6.

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1988]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- Reu, Pandit Bisheshwar Nath (1997) [1933]. History of the Rashtrakutas (Rathodas). Jaipur: Publication Scheme. ISBN 81-86782-12-5.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2006) [2006]. The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24500-8.

- Rao, Seshagiri, L.S (1988) [1988]. "Epic (Kannada)". In Amaresh Datta (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921]. Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0063-0.

- Rice, B.L. (2001) [1897]. Mysore Gazetteer Compiled for Government-vol 1. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0977-8.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [1999]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age Publishers. ISBN 81-224-1198-3.

- Singh, Upinder (2008) [2008]. A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India:From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. India: Pearsons Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Thapar, Romila (2003) [2003]. Penguin History of Early India: From origins to AD 1300. New Delhi: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-302989-4.

- Vaidya, C.V. (1979) [1924]. History of Mediaeval Hindu India (Being a History of India from 600 to 1200 A.D.). Poona: Oriental Book Supply Agency. OCLC 6814734.

- Warder, A.K. (1988) [1988]. Indian Kavya Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0450-3.

Web

- Arthikaje. "The Rashtrakutas". History of karnataka. OurKarnataka.Com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- Kamat, Jyotsna. "The Rashtrakutas". Dynasties of the Deccan. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- Sastri & Rao, Shama & Lakshminarayan. "South Indian Inscriptions-Miscellaneous Inscriptions in Kannada". Rashtrakutas. Retrieved 3 February 2007.