Reigate

Reigate (/ˈraɪɡeɪt/ RY-gate) is a town in Surrey, England, around 19 miles (30 km) south of central London. The settlement is recorded in Domesday Book in 1086 as Cherchefelle and first appears with its modern name in the 1190s. The earliest archaeological evidence for human activity is from the Paleolithic and Neolithic, and during the Roman period, tile-making took place to the north east of the modern centre.

| Reigate | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Old Town Hall, High Street | |

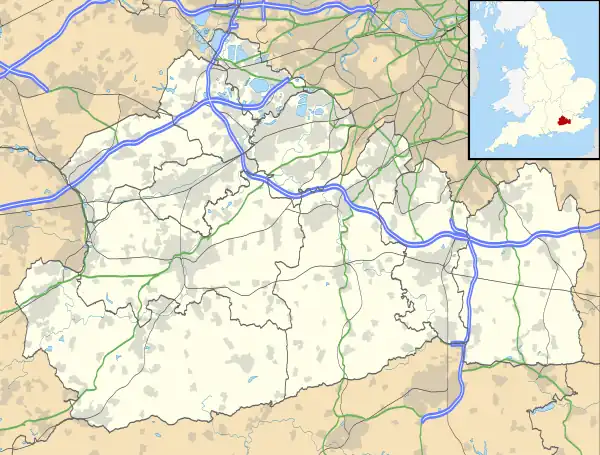

Reigate Location within Surrey | |

| Population | 21,820 (electoral definition) or 22,123 (Built-up Area)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ2649 |

| • London | 19 mi (30 km) N |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Reigate |

| Postcode district | RH2 |

| Dialling code | 01737 |

| Police | Surrey |

| Fire | Surrey |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

A motte-and-bailey castle was erected in Reigate in the late 11th or early 12th century. It was originally constructed of timber, but the curtain walls were rebuilt in stone about a century later. An Augustinian priory was founded to the south of the modern town centre in the first half of the 13th century. The priory was closed during the Reformation and was rebuilt as a private residence for William Howard, the 1st Baron Howard of Effingham. The castle was abandoned around the same time and fell into disrepair.

During the medieval and early modern periods, Reigate was primarily an agricultural settlement. A weekly market began no later than 1279 and continued until 1895. Key crops included oats, hops and flax, but there is no record of rye being grown in the local area. The economy initially declined in the 18th century, as new turnpike roads allowed cheaper goods made outside the town to become available, undercutting local producers. Following the arrival of the railways in the mid-19th century, Reigate began to expand and the sale of much of the priory estate in 1921 released further land for housebuilding.

Since 1974, Reigate has been one of four towns in the borough of Reigate and Banstead and is part of the London commuter belt. The borough council is based at the town hall in Castlefield Road and Surrey County Council has its headquarters at Woodhatch Place. Much of the North Downs, to the north of Reigate, is owned by the National Trust, including Colley Hill, 722 feet (220 m) above ordnance datum (OD) and Reigate Hill 771 feet (235 m) above OD.

Toponymy

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Reigate appears as Cherchefelle and in the 12th century, it is recorded as Crichefeld and Crechesfeld. The name is thought to mean "open space by the hill or barrow".[2][3]

The name "Reigate" first appears in written sources in the 1190s. Similar forms are also recorded in the late medieval period, including Reigata in 1170, Regate in 1203, Raygate in 1235, Rigate in 1344 and Reighgate in 1604. The name is thought to derive from the Old English rǣge meaning "roe deer" and the Middle English gate, which might indicate an enclosure gate or pass through which deer were hunted.[4][5] It has also been suggested that the "rei" element may have evolved from the Middle English ray, meaning a marshland or referring to a stream;[6] this theory is considered unlikely as the Old English form of this word is ree rather than rey.[4][note 1]

Woodhatch may derive from the Old English word hæc meaning "gate", and the name may mean "gate to the wood". It is possible, in this instance, that the "wood" referred to is the Weald.[8][9] In 1623, a survey of the manor of Reigate noted a "Bowling Alley lying before the gate of the Tenement called Woodhatch".[10] Alternatively, the name may derive from that of a local resident: A "Thomas ate Chert" is recorded as living at the settlement in the early 14th century and "Woodhatch" might instead mean "woodland of the ate Chert family".[7]

Geography

Location and topography

Reigate is in central Surrey, around 19 mi (30 km) south of central London and 9 mi (14 km) north of Gatwick Airport.[11] The town is in the Vale of Holmesdale, below the North Downs escarpment. The average elevation in the centre is 80 m (260 ft) above ordnance datum (OD) and the area is drained by the Wallace Brook and its tributaries, which feed the River Mole.[12][13]

Geology

Woodhatch lies on the Weald Clay, a sedimentary rock primarily consisting of mudstone that was deposited in the early Cretaceous. Much of Reigate is on the strata of the Lower Greensand Group. This group is multi-layered and includes the sandy Hythe Beds overlain by the clayey Sandgate Beds, which together form the high ground of Priory Park.[14][15] Reigate Heath and the town centre are on quartz-rich Folkestone Beds[16] and the water-filled part of the castle moat is dug into narrow band of clay present in the sandstone.[17] To the north of the railway line is the Gault Formation, a stiff, blue-black, shaly clay, deposited in a deep-water marine environment.[18] At the base of the North Downs is a thin outcrop of Upper Greensand, above which lies the Chalk Group.[19]

.jpg.webp)

Weald clay was dug for brickmaking at Brown's Brickyard in Woodhatch.[20] Building sand was excavated from Barnards Pit, to the west of the town, and at Wray Common Road to the east.[21] Seams of silver sand which occur in the Folkestone Beds were quarried for glass making and the caves beneath the castle may originally have been excavated for this purpose, before being used as cellars. There is also evidence of ironstone extraction in the town, although this practice is thought to have ceased by 1650.[22]

Reigate Stone was mined from the Upper Greensand from medieval times until the mid-20th century[23] and was used in the construction of several local buildings, including the castle, Reigate Priory and St Mary's Church. To the north of the town are the remains of several old chalk pits[24] and lime is thought to have been produced at a site at the base of Colley Hill, although the age of the workings is uncertain.[25]

History

Early history

.jpg.webp)

The earliest evidence of human activity in the Reigate area is a triangular stone axe from the Paleolithic, which was found in Woodhatch in 1936.[27] Worked flints from the later Neolithic have been found on Colley Hill.[28] Finds from the Bronze Age include a gold penannular ring, dated to c. 1150 – c. 750 BCE,[29] and a barbed spearhead from Priory Park.[30] The eight barrows on Reigate Heath are thought to date from the same period, when the surrounding area may have been marshland.[31][32]

During the Roman period, the Doods Road area was a centre for tile-making.[34] An excavation in 2014 uncovered the remains of a 2nd- or 3rd-century kiln with several types of tile, identified as tegulae, imbrices and pedales.[33][note 2] Artefacts discovered to the south west of the town centre in 2011 suggest that there was a high-status villa nearby. Coins from the reigns of Vespasian (69-79), Hadrian (117–138), Severus Alexander (222–235) and Arcadius (383-408), indicate that there was Roman activity in the local area throughout the occupation of Britain.[36]

The former name Cherchefelle suggests that the most recent period of permanent settlement in Reigate began in Anglo-Saxon times.[35] The main settlement is thought to have been located in the area of the parish church, to the east of the modern centre, although much of the population was probably thinly dispersed around the parish.[37] Excavations in Church Street in the late 1970s uncovered a Saxon glass jar and remains of a skeleton of uncertain age,[38] but archaeological evidence from this period elsewhere in the town is sparse.[35]

Governance

Reigate appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Cherchefelle. It was held by William the Conqueror, who had assumed the lordship in 1075 on the death of Edith of Wessex, widow of Edward the Confessor. The settlement included two mills worth 11s 10d, land for 29 plough teams,[note 3] woodland and herbage for 140 swine, pasture for 43 pigs and 12 acres (4.9 ha) of meadow. The manor rendered £40 per year in 1086 and the residents included 67 villagers and 11 smallholders.[40][41] The Domesday Book also records that the town was part of the larger Hundred of Cherchefelle.[39]

The non-corporate Borough of Reigate, covering roughly the town centre, was formed in 1295. It elected two MPs until the Reform Act of 1832 when it lost one.[42] In 1868, Reigate borough was disenfranchised for corruption,[43] but representation in the House of Commons was restored to the town in the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.[44]

The manor of Cherchefelle was granted to William de Warenne when he became Earl of Surrey c. 1090 and under his patronage, Reigate began to thrive. The castle was constructed shortly afterwards and the modern town was established to the south in the late 12th century.[45] An Augustinian priory, founded by the fifth Earl of Surrey, is recorded in 1240.[35] By 1276, a regular market was being held and a record of 1291 describes Reigate as a Borough.[45] On the death of the seventh Earl, John de Warenne, in 1347, the manor passed to his brother-in-law, Richard Fitzalan, the third Earl of Arundel. In 1580 both Earldoms passed through the female line to Phillip Howard, whose father, Thomas Howard, had forfeited the title of Duke of Norfolk and had been executed for his involvement in the Ridolfi plot to assassinate Elizabeth I.[46] The dukedom was restored to the family in 1660, following the accession of Charles II.[47]

Reforms during the Tudor period reduced the importance of manorial courts and the day-to-day administration of towns such as Reigate became the responsibility of the vestry of the parish church.[48] By the early 17th century, the 20 km2 (5,000-acre) ecclesiastical parish had been divided for administrative purposes into two parts: the "Borough of Reigate", which broadly corresponded to the modern town centre, and "Reigate Foreign", which included the five petty boroughs of Santon, Colley, Woodhatch, Linkfield and Hooley.[49][note 4] The two parts were reunited in 1863 as a Municipal Borough with a council of elected representatives chaired by a mayor.[49][50] The Borough was extended in 1933 to include Horley, Merstham, Buckland and Nutfield.[51]

The Local Government Act 1972 created Reigate and Banstead Borough Council, by combining the Reigate Borough with Banstead Urban District and the eastern part of the Dorking and Horley Rural District.[note 5] Since its inception in 1974, the council has been based in the Town Hall in Castlefield Road, Reigate.[52]

Reigate Castle

Reigate Castle was built in the late 11th or early 12th century, most likely by William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Surrey. Taking the form of a motte-and-bailey castle, it was originally constructed of timber, but the curtain walls were rebuilt in stone around a century later. A water-filled moat section was dug into the clay on the north side and a dry ditch was excavated around the remainder of the structure. The large size of the motte indicates that the castle was designed both as a fortification and as the lord's residence from the outset.[54][note 6]

Following the dissolution of the monasteries, the lords of the manor moved their primary residence to Reigate Priory, to the south of the town. The castle was allowed to decay, with only small outlays recorded in the manor accounts for repairs, until 1686, when the buildings were reported as ruinous. Much of the masonry was most likely removed for local construction projects, but in around 1777, Richard Barnes, who rented the grounds, built a new gatehouse folly using the remaining stone. A century later, the Borough Council was granted a long lease on the property, which had been turned into a public garden.[57][note 7] Regular tours of the caves beneath the castle are run by the Wealden Cave and Mine Society.[59]

Reigate Priory

William de Warenne, the fifth Earl of Surrey, is thought to have founded the Augustinian priory at Reigate before 1240.[61][note 8] Early documents refer to the priory as a hospital, but in 1334 it is described as a convent and thereafter as a purely religious institution.[63] The priory was built to the south of the modern town centre, close to the Wray stream, a tributary of the Wallace Brook, and a series of fish ponds was constructed in the grounds.[62] Although the exact layout is uncertain, the buildings are thought to have been arranged around a central square cloister, with the church on the north side and the refectory on the south.[64] The priory was created as a sub-manor of Reigate and was granted several local farms including one in each of Salford and Horley. It also received the manor of Southwick in West Sussex, which it gave to the Bishop of Winchester in 1335 and to compensate for the loss of income, it was awarded the annual pension from St Martin's Church in Dorking.[63][note 9][note 10] At the time of its dissolution in 1536, Reigate Priory was the least wealthy of all the Surrey religious houses.[63]

In 1541, Henry VIII granted the former priory to William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Effingham, the uncle of Catherine Howard.[66][67] The old church was converted to a private residence and the majority of the rest of the buildings were demolished.[68][note 11] In 1615, the estate was inherited by Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, who had led the English fleet against the Spanish Armada.[69] On his death in 1624, it became the residence of his widow, Anne St John,[66] and then passed in 1639 to his daughter, Elizabeth, who had married John Mordaunt, 1st Earl of Peterborough.[70] In 1681, her grandson, Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough, sold the priory to John Parsons, one of the MPs for Reigate and the former Lord Mayor of London.[71][72][note 12]

Richard Ireland, who purchased the priory in 1766 following the death of Humphrey Parsons, is primarily responsible for the appearance of the buildings today.[74] A fire destroyed much of the west wing and Ireland commissioned its rebuilding. He also shortened the length of the east wing from 75 to 25 ft (22.9 to 7.6 m), so that the house was symmetrical. The walls of the two wings were raised to match the main north range and the Tudor features including the windows were replaced with Georgian fixtures. Finally the south-facing walls were refaced with a cement stucco.[75] Following Ireland's death in 1780, the priory passed through a succession of owners, including Lady Henry Somerset, who remodelled the grounds between 1883 and 1895, creating a sunken garden.[76] Following her death in 1921, the estate was divided for sale and much of the land was purchased for housebuilding.[77]

The final private owner of the house was the racehorse trainer, Peter Beatty, who sold it to the Mutual Property Life and General Insurance Company, which relocated from London for the second half of the Second World War. In 1948, the borough council bought the grounds, having secured them as Public Open Space three years earlier.[78][79] Also in 1948, the Reigate Priory County Secondary School opened in the main priory building, with 140 children aged 13 and 14. In 1963 the boys moved to Woodhatch School and the Priory School continued as an all-girls secondary school. In 1971, the secondary school closed and Holmesdale Middle School, which had been founded in 1852, moved to the priory.[80]

Transport and communications

In medieval times, the main road north from Reigate followed Nutley Lane, climbing Colley Hill in the direction of Kingston upon Thames, from where produce and manufactured items could be transported via the River Thames.[81][note 13][note 14] Although the direct route to London via Merstham had a less severe gradient, it appears to have been little used for the transport of goods.[81] The manor of Reigate was responsible for maintaining the roads in the local area, but repairs were carried out infrequently[83] and improvements were often only funded by private donations.[84][note 15] In 1555, the responsibility for local infrastructure was transferred to the parish, and separate surveyors were employed for the Borough and for Reigate Foreign. The inefficiency created by this division resulted in frequent complaints and court cases relating to the poor state of the roads[83] and so, in 1691, local justices of the peace were given the role of appointing the surveyors.[85]

The first turnpike trust in Surrey was authorised by Parliament in 1697 to improve the road south from Woodhatch towards Crawley. The new road took the form of a bridleway, laid alongside the existing causeway between the River Mole crossing at Sidlow and Horse Hill, and was unsuitable for wheeled vehicles.[86] Repairs were also carried out on the route between Reigate and Woodhatch under the same Act.[87] A second turnpike was authorised in 1755, to improve the route from Sutton to Povey Cross, near Horley, which involved creating a new road north from Reigate over Reigate Hill. A cutting was excavated at the top of the hill, using a battering ram to break up the underlying chalk. The new route was completed the following year[88] and the old road via Nutley Lane was blocked at Colley Hill.[89][note 16] In 1808, a second turnpike to the north was opened to Purley via Merstham. The new trust was required to pay £200 per year to the owners of the Reigate Hill road, in compensation for lost tolls.[92]

.jpg.webp)

Two improvements to the road network in the town centre took place in the early nineteenth century. Firstly, in 1815, the Wray Stream, was culverted to improve the drainage and road surface of Bell Street. Secondly, Reigate Tunnel, the first road tunnel in England, was constructed at the expense of John Cocks, 1st Earl Somers the lord of the manor. Opened in 1823, it runs beneath the castle and links Bell Street to London Road. It enabled road traffic to bypass the tight curves at the west end of the town centre, but is now only used by pedestrians.[93][94] The Borough Council became responsible for local roads on its formation in 1865. The final tolls were removed from the turnpikes in 1881.[95]

The first station to serve Reigate area was at Hooley, Earlswood and opened in 1841. The following year, the South Eastern Railway opened the railway station at Redhill, which was initially named Reigate Junction.[96] The railway line through Reigate was constructed by the Reading, Guildford and Reigate Railway and opened in 1849. It was designed to provide an alternative route between the west of England and the Channel ports, and serving intermediate towns was a secondary concern.[97][note 17] Electrification of the section of line from Reigate to Redhill was completed on 1 January 1933.[99]

In February 1976, Reigate was joined to the UK motorway system when the M25 was opened between Reigate Hill and Godstone.[100] The section to Wisley via Leatherhead was opened in October 1985.[101]

Economy and commerce

From much of its early history, Reigate was primarily an agricultural settlement. At the time of the Norman conquest, the common fields covered some 3,500 acres (1,400 ha) and in 1623 the total area of arable land was around 4,500 acres (1,800 ha).[102] From the early 17th century, the manor began to specialise in the production of oatmeal for the Royal Navy, possibly due to the influence of Admiral Charles Howard, who lived at the priory.[103][note 18] By 1710, 11.5% of the population was employed in cereal processing, but the trade dwindled in the mid-18th century and had ceased by 1786.[103] Until the early 18th century, most goods were traded locally, but thereafter, London is thought to have become the most important market for produce.[105]

The market in Reigate is first recorded in 1279, when John de Warenne, the 6th Earl of Surrey, claimed the right to hold a weekly market on Saturdays and five annual fairs. His son John, the 7th Earl, was granted permission to move the event to Tuesdays in 1313.[106] The original market place was to the west of the castle, in the triangle of land now bordered by West Street, Upper West Street and Slipshoe Street (where the former route to Kingston diverged from the road to Guildford). It moved to the widest part of the High Street, close to the junction with Bell Street, in the 18th century.[107] Cattle ceased to be sold in the late 19th century and the market closed in 1895, in part as a result of the opening of a fortnightly market in Redhill in 1870.[108]

Reigate has two surviving windmills: a post mill on Reigate Heath[109] and a tower mill on Wray Common.[110] In the early modern period, the parish had at least three other windmills[108] and about a dozen animal-powered mills for oatmeal. In addition, there were watermills along the southern boundary of the parish, on the Mole and Redhill Brook.[111]

Although the opening of the Reigate Hill turnpike in 1755 provided an easier route to transport produce and manufactured items to London, the new road appears initially to have had a negative impact on the local economy, as goods produced elsewhere became cheaper than those made in the town itself.[112] As a result, there was little growth in the population between the 1720s and 1821.[113] In the late 18th century, the prosperity of the town began to recover as it became as stopping point on the London to Brighton coaching route.[112][note 19] In 1793, over half of the traffic on the Reigate Hill turnpike was bound for the south coast and numbers swelled as a result of troop movements during the Napoleonic Wars.[114] The opening of the turnpike through Redhill, appears to have had little initial impact on the numbers travelling through the town, as travellers preferred to break their journeys in Reigate, rather than bypassing the town to the east.[114]

Residential development

Reigate began to expand following the arrival of the railway lines in the 1840s. At first, development was focused in the east of the parish. A new settlement, initially known as Warwick Town, was established on land owned by Sarah Greville, Countess of Warwick in the 1820s and 1830s. In 1856, the post office relocated its local branch to the growing village and the area became known as Redhill. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, Redhill expanded eastwards towards the Reigate town centre and the two towns are now contiguous.[115]

A new residential area was established at Wray Park, to the north of Reigate town centre, in the 1850s and 1860s. St Mark's Church was built to serve the new community. Doods Road was constructed in around 1864 and Somers Road, to the west of the station, followed shortly afterwards. In 1863, the National Freehold Land Society began to develop the Glovers Field estate, to the south east of the town centre, and also led efforts to build houses at South Park, to the west of Woodhatch.[116]

At the end of the 19th century, the estates of several large houses were broken up, releasing further land for development.[116] Glovers and Lesborne Roads, to the south east of the centre, were developed by the National Freehold Land Company c. 1893.[117][note 20] The Great Doods estate, between the railway line and Reigate Road, was sold in 1897 and the first houses in Deerings Road appeared shortly afterwards.[118] A major development occurred in 1921, when the Reigate Priory estate (which included much of the land in the town) was sold, enabling existing leaseholders to purchase the freehold of their properties and freeing up further land for construction.[77][119]

In the early 20th century, South Park continued to expand to the south and east. The sale of Woodhatch Farm in the 1930s released the land for housebuilding. Further expansion in Woodhatch occurred in the 1950s, with the construction of council housing on the Rushetts Farm estate.[121]

Reigate in wartime

Although little fighting took place in Surrey during the Civil War, the Reigate Hundred was required to provide 80 men for the Parliamentarian army, but a force of only 60 was raised, including a captain and lieutenant. Troops were garrisoned in the town and by the summer of 1648, serious discontent was rising in the local area as a result.[122] The Royalist, Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, raised a fighting force and marched from Kingston to Reigate where his men plundered local property and briefly occupied the half-ruined castle. Parliamentary troops under Major Lewis Audley were sent to confront Rich, but he withdrew first to Dorking and then the following day back to Kingston. The withdrawal of the Royalists from Reigate was the final incident in the Civil War south of the River Thames before the execution of Charles I in 1649.[122][123]

In September 1914, Reigate became a garrison town. Members of the London's Own Territorials were billeted locally whilst undergoing training in the area[124] and Reigate Lodge was used as an Army Service Corps supply depot.[125] Reigate railway station was closed between January 1917 and February 1919 as a wartime economy measure.[126]

By the end of the First World War, there were three temporary hospitals for members of the armed forces in Reigate. The Hillfield Red Cross Hospital opened on 2 November 1914 and was equipped with an operating theatre and 50 beds. As well as treating injured soldiers transported home from overseas, the facility also treated troops garrisoned locally.[127] The Kitto Relief Hospital in South Park opened on 9 November 1914, initially as an annex to the Hillfield Hospital, but from 28 September 1915 it was affiliated to the Horton Hospital in Epsom.[128] The Beeches Auxiliary Military Hospital, on Beech Road, was opened in March 1916 with 20 beds, but expanded to 40 beds that October. The hospital relocated to a larger facility in the same road in July 1917 and became affiliated with the Lewisham Military Hospital two months later.[129][130]

Some 5000 evacuees from London were sent to the Reigate and Redhill area at the start of the Second World War in September 1939,[131] but by February of the following year around 2000 had returned home.[132] The caves beneath Reigate Castle were converted for use as public air raid shelters[131] and the first bombing raid on the town took place on 15 August 1940.[133] There was a succession of raids in November 1940, including on the 7th when Colley Hill and Reigate Hill were attacked.[134] Towards the end of the war, in 1944, the Tea House café on top of Reigate Hill was destroyed by a V-1 flying bomb.[135]

For much of the war, Reigate was the headquarters of the South Eastern Command of the British Army.[136][137] The defence of the town was the responsibility of the 8th Surrey Battalion of the Home Guard,[138] but the East Surrey Water Company and the London Passenger Transport Board formed separate units to defend local infrastructure.[139][140] Tank traps in the castle grounds were among the defences installed in the town.[136] Before being deployed to the Western Front, the 1st Battalion of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment (part of the Canadian Army, was encamped locally.[141][note 21] On 19 March 1945 a U.S. Air Force B17G, returning from a bombing raid in Germany, crashed into Reigate Hill in low-visibility conditions. Two memorial benches, carved in the shape of wing tips, were installed as a memorial at the crash site 70 years later.[143]

National and local government

The town is in the parliamentary constituency of Reigate and has been represented at Westminster since May 1997 by Conservative Crispin Blunt.[144] His predecessor, George Gardiner, was elected MP in 1974, but defected from the Conservatives to the Referendum Party two months before the 1997 general election.[145][146] Geoffrey Howe, later briefly Deputy Prime Minister under Margaret Thatcher, represented Reigate from 1970 to 1974.[147]

In January 2021, the Surrey County Council moved its headquarters from Kingston upon Thames to Woodhatch Place at 11 Cockshott Hill, in the Woodhatch area of Reigate.[148][149] Two councillors, elected every four years, represent the town:[150]

| Election | Member |

Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[151] | Victor Lewanski | Reigate | |

| 2021[152] | Catherine Baart | Earlswood and Reigate South | |

Six councillors sit on Reigate and Banstead borough council, which operates a council-elected-in-thirds system, allowing electors to vote for one candidate in three out of every four years:[153]

| Election | Member |

Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014[154] | Michael Blacker | Reigate | |

| 2018[155] | Victor Lewanski | Reigate | |

| 2023[156] | Kate Fairhurst | Reigate | |

| 2016[157] | James King | South Park and Woodhatch | |

| 2021[158] | Paul Chandler | South Park and Woodhatch | |

| 2022[159] | Andrew Proudfoot | South Park and Woodhatch | |

The borough is twinned with Brunoy (Île-de-France, France) and Eschweiler (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany).[160]

Demography and housing

In the 2011 Census, the population of the Reigate built-up area, including Woodhatch, was 22,123.[1]

| Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reigate and Woodhatch | 22,123 | 9,036 | 34.5 | 38.5 | 316 |

| Regional average | 35.1 | 32.5 | |||

| Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reigate and Woodhatch | 2,487 | 2,853 | 1,378 | 2607 | 6 | 9 |

Across the South East Region, 28% of homes were detached houses and 22.6% were apartments.[1]

Public services

Utilities

Reigate Water Works Company was established in 1858.[161] It opened a plant on Littleton Lane the following year, to supply drinking water to the town from the Wallace Brook.[162] It was purchased by the East Surrey Water Company in 1896,[161] which closed the Reigate works after extending its mains network to the town from Caterham.[162][note 22] The first sewerage system in Reigate was installed in 1876 and included a main outfall sewer running under Bell Street via Woodhatch to the treatment works at Earlswood Common.[164]

Reigate Gas Company was formed in 1838 and opened a gasworks on London Road a year later.[162][165] Initially it was contracted to supply gas for 28 street lights in the town centre, but by 1860, increasing domestic demand necessitated the opening of a larger facility at the north end of Nutley Lane. In 1921, the Reigate company was taken over by the Redhill Gas Company, which had been formed in 1865.[162]

An electricity generating station was authorised by the Reigate Electric Lighting Order 1897 and constructed in a former sand quarry next to the railway line off Wray Common Road.[166] On opening it had an installed capacity of 230 kW, but by the time of its closure in 1936, the maximum power output had risen to 2.7 MW.[165] Under the Electricity (Supply) Act 1926, Reigate was connected to the National Grid, initially to a 33 kV supply ring, which linked the town to Croydon, Dorking, Epsom and Leatherhead. In 1939, the ring was connected to the Wimbledon-Woking main via a 132 kV substation at Leatherhead.[167][165]

Emergency services

The Borough police force was founded in 1864 and initially consisted of a superintendent, a sergeant and eight constables.[164] The original police station was in West Street, but was moved to the High Street in around 1866 and to the Municipal Buildings around the turn of the century. A new police station was opened in Reigate Road in 1972, coinciding with the merger of the Borough force with the Surrey Constabulary.[168]

In 1809, two fire engines were presented to the vestry, which was charged with appointing a group of six men to operate it when needed. The brigade was expanded to 12 members in 1854.[169] A new fire station, with a four-storey tower and a pagoda style roof, opened next to the new town hall in Castlefield Road in 1901.[170][171] The brigade moved to Croydon Road in 1955.[172] In 2021, the fire authority for Reigate is Surrey County Council and the statutory fire service is Surrey Fire and Rescue Service.[173] The Ambulance Community Response Post, located at the fire station, is run by the South East Coast Ambulance Service.[174]

Healthcare

The nearest accident & emergency department is at East Surrey Hospital (2.3 mi (3.7 km)).[175] As of 2023, the GP practice is in Yorke Road.[176]

Economy

At one time the airline Air Europe had its head office in Europe House in Reigate.[177] Redland plc the FTSE 100 building materials company was headquartered in Reigate before its acquisition by Lafarge and its former headquarters are now occupied by the insurance company esure.[178]

Canon UK had its headquarters on the southern outskirts of Reigate.[179] The building, opened by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in 2000, has won numerous design and 'green' awards.[179][180]

The European headquarters of Kimberly-Clark are on London Road in the town, just south of Reigate railway station.[181] Further along London Road towards the town centre can be found the former European headquarters of Willis Towers Watson, prior to the merger with Willis where the global and British headquarters relocated to Lime Street in London.[182]

Pilgrim Brewery was founded in 1982[183] and moved to West Street in 1984. It was the first new brewery to be established in Surrey for over a century.[184]

Transport

Public transport

Reigate railway station is a short distance to the north of the town centre and is managed by Southern. The operator runs services to London Victoria via Redhill and East Croydon. Trains to Reading via Guildford and to Gatwick Airport via Redhill are run by Great Western Railway.[185]

Reigate is linked by bus to Redhill and the surrounding towns and villages in east Surrey. Operators serving the town include Compass Bus, London General, Metrobus and Southdown. Routes 420 and 460 link the town to the East Surrey Hospital and the latter also runs to Gatwick Airport.[186][187]

Cycle routes and long-distance footpaths

The Surrey Cycleway passes through Woodhatch.[188]

The Greensand Way, a 108 mi (174 km) long-distance footpath from Haslemere, Surrey to Hamstreet, Kent, passes through Reigate Park to the south of the town centre.[189][190] The North Downs Way, between Farnham and Dover, runs from west to east across Colley Hill and Reigate Hill.[191]

Education

Maintained schools

There are several primary schools in Reigate. Dovers Green School and Wray Common Primary School are members of the Greensand Multi-Academy Trust.[192][193] Sandcross Primary School is part of the Everychild Trust.[194]

Reigate Parish Church Primary School was founded as the Reigate National School. Originally in West Street, it moved to London Road in 1854 and then to Blackborough Road in 1995.[195]

Reigate Priory Junior School traces its origins to a non-denominational school, founded in 1852 in the High Street. It moved to Holmesdale Road in the 1860s and in 1993 moved to the priory, taking over the classrooms previously used by Reigate Priory Middle School.[80] The school educates children between the ages of 7 and 11 and is due to move to new premises on Cockshott Hill in 2023.[196]

Reigate School is a coeducational secondary school in Woodhatch. It educates children aged 11 to 16. It is part of the Greensand Multi-Academy Trust.[197] It opened as the Woodhatch County Secondary School in September 1958.[198]

The Royal Alexandra and Albert School traces its origins to an orphanage for children of Dissenters, founded in Hoxton, London in 1759. The orphanage expanded rapidly and by 1769 had 28 boys and 25 girls between the ages of 6 and 9 in its care. It relocated several times during the following two centuries and, in 1943 it was renamed the Royal Alexandra School and was based on a 180-acre (73 ha) site at Duxhurst, near Salfords.[199] A separate institution, the Royal Albert Orphan Asylum was founded near Bagshot in 1864 and admitted its first 100 children in December of that year.[200] It was renamed the Royal Albert School in 1942.[201] The management of the Royal Alexandra and the Royal Albert Schools was merged in 1948 and the new organisation purchased the Gatton Park estate. The following year, an Act of Parliament was passed to formally amalgamate the two institutions. Boarding accommodation was constructed at Gatton Park in 1950 and pupils were relocated from the Bagshot and Duxhurst sites in stages between 1948 and 1954.[200] Today, the Royal Alexandra and Albert School is a coeducational maintained boarding school,[202] educating 1125 children between the ages of 7 and 18.[203]

Reigate College is a coeducational sixth form college for students aged 16 to 19.[204] It opened in 1976 on Castlefield Road, to the east of the town centre.[205] The main building, constructed in 1927, was previously occupied by the Reigate County School for Girls and was designed by the architecture firm Jarvis and Porter.[206][207]

Independent schools

Micklefield School was founded in 1910 and takes its name from its original location, Micklefield House in Evesham Road. It moved to its current site in Somers Road, to the north of the town centre, in 1925.[208] In 2021, Micklefield is a coeducational, independent day school for children aged 2 to 11.[209]

Reigate St Mary's School was founded in 1950 as the choir school for St Mary's Church. Initially for boys only, it became coeducational in 2003, when it was made the principal feeder school for Reigate Grammar School.[210] In 2021, Reigate St Mary's is a coeducational day school for children aged 2 to 11.[211]

Reigate Grammar School traces its origins to 1675, when Henry Smith, an Alderman of the City of London, left a bequest of £150 for the purchase of land for a "free school". The first master, Revd John Williamson, was the vicar of Reigate and for the first two centuries, several headmasters were also parish priests. The school became a grammar school in 1861 and around this time many of the original buildings were replaced. The school was taken over by Surrey County Council under the Education Act 1944, but became independent in 1976. In the same year, girls were admitted to the sixth form and the school became fully coeducational in 1993. It merged with Reigate St Mary's Prep School and Chinthurst School in 2003 and 2017 and, as of 2021, the three school together educate around 1,500 pupils aged from 3 to 18. An international division was created in 2017, to work in partnership with the Kaiyuan Education Fund, to establish up to five schools in China.[212]

Dunottar School was founded in 1926 and is named after Dunottar Castle in Aberdeenshire, where the Scottish Crown Jewels were kept between 1651 and 1660. In 1933, the school moved to its current site, the former High Trees house, which had been built in 1867.[213][214] In 2021, Dunottar is a co-educational independent day school for children aged 11 to 18.[215] It became part of United Learning in 2014.[213]

Other schools

Reigate Valley College at Sidlow, just south of the town, is a former pupil referral unit that educates pupils who have had behavioural issues in mainstream schools.[216] There are two schools in the town for students with special educational needs: Brooklands School on Wray Park Road[217] and Moon Hall College at Flanchford Bridge near Leigh.[218]

Places of worship

Church of St Mary Magdalene

_(June_2013).JPG.webp)

The first record of a church at Reigate is from the late 12th century, when the church of Crechesfeld was presented to the Priory of St Mary Overie by Hamelin and Isabel de Warenne, the Earl and Countess of Surrey.[219] At the time of the gift, the church is thought to have consisted of a nave, chancel and possibly a central tower.[220] The oldest parts of today's St Mary's Church date from c. 1200.[221] The building was extended several times in the late medieval period, including the additions of the north and south aisles in the mid-late 13th century,[220] the south chancel chapel in the 14th century[221] and the relocation of the tower to the west end in the first half of the 15th century.[220] Two phases of reconstruction took place in Victorian times. In 1845, the architect, Henry Woodyer, was responsible for renewing the local Reigate Stone walls and, in 1874–7, George Gilbert Scott Jr. installed new roofing and refaced the tower in Bath Stone.[221]

The medieval rood screen, separating the chancel from the nave, was restored by Woodyer, who was also responsible for much of the current stained glass. There are several 17th- and 18th-century monuments inside the church, the largest of which is a memorial to Richard Labroke (d. 1730) who is depicted in Roman dress, flanked by the figures of Justice and Truth.[221]

Reigate Mill Church

Reigate Heath Windmill was built c. 1765 and was last worked by wind in 1862.[222] The weatherboarded upper section of the post mill holds the sails and sits above the brick roundhouse below.[223] The roundhouse was converted into a chapel of ease to the Church of St Mary Magdalen in 1880 and services are held in the building during the summer months. It is thought to be the only windmill to be used as a church in England.[222]

Reigate Heath Church

Reigate Heath Church, on Flanchford Road, was built in 1907 as a chapel of ease to St Mary Magdalen. It is constructed from corrugated galvanised iron and is typical of the tin tabernacles, built around the same time.[224][225]

St Mark's Church

St Mark's Church, in Alma Road, was opened in 1860 to serve a new area of housing, under construction to the north of the railway station.[226] It was designed by the architects firm, Field & Hilton, and is built in Reigate Stone.[227] The tower and spire were added in 1863, but the spire was demolished in 1919. The church was heavily damaged during the Second World War, necessitating the demolition of the south transept. Most of the windows were destroyed by bomb blasts and a new East Window, designed by Francis Spear, was installed in 1955.[226]

St Philip's Church

St Philip's Church, to the north west of the town centre, was built in 1863, originally as a chapel of ease to St Mark's Church.[228] The pulpit dates from 1898 and the reredos was installed in 1919.[229] Following the First World War, the east end of the church was reordered to raise the floor level and the chancel was enlarged into the nave in 1957.[230]

St Luke's Church

St Luke's Church, to the south of the town, was opened in 1871. It is constructed from Reigate Stone and is built in the Gothic style. The west end was damaged during a storm in the 1960s and the affected wall was replaced by a clear-glazed window. The church was extended to the west, with the addition of an annex, which provides accommodation for the Winter Night Shelter.[231]

Reigate Methodist Church

_(3).jpg.webp)

Although John Wesley visited Reigate four times between 1770 and 1775,[232] the first Methodist chapel was not established in the town until 1858. The current church, in the High Street, was built in 1884.[233][234]

Catholic Church of the Holy Family

The Catholic Church of the Holy Family was built in Yorke Road, on land donated by a local benefactor. It was consecrated in 1939. A mass centre was established in a wooden building in Woodhatch, but was closed in 2003 after almost 50 years of use.[235]

Culture

Art

Reigate Priory Museum holds an early-16th century portrait of John Lymden, the final Prior of Reigate.[236] The Town Hall holds several artworks, including paintings by Henry Tanworth Wells (1828—1903),[237] George Leon Little (1862—1941)[238][239][240] and George Hooper (1910—1994).[241] Landscapes depicting scenes of the Reigate area by the artists Alfred Walter Williams (1823—1905), James Thomas Linnell (1826—1905) and Albert Ernest Bottomley (1873—1950) are held by Leicester Museum and Art Gallery,[242] the Royal Pavilion and Museums Trust, Brighton,[243] and Derby Museum and Art Gallery respectively.[244] Among the works of public art in the town is a statue of the ballet dancer, Margot Fonteyn, by the artist Nathan David, which was installed at the south end of London Road in 1980.[245][246][note 23]

Literature

Reigate is the setting for the Sherlock Holmes short story "The Adventure of the Reigate Squire" (also known as "The Adventure of the Reigate Squires" and "The Adventure of the Reigate Puzzle"). It is one of twelve stories featured in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.[247][248]

Sport

Association football

Reigate Priory F.C. was founded in 1870, just seven years after The Football Association was created. It has played its home games at its ground in Park Lane for the entirety of its history.[249]

South Park F.C. was founded in 1897 and has been a member of the Redhill & District Football League since its inception. The club initially played its home games in upper South Park, between Crescent Road and Church Road. In the late 1920s, it moved to its current premises in Whitehall Lane.[250]

Cricket

Reigate Priory Cricket Club was founded in 1852, but it is believed that the sport has been played in the town since the 1770s.[251][note 24] The first recorded match at the club ground took place in 1853 between teams from East Surrey and West Sussex.[252]

Golf

Reigate Heath Golf Club was founded in 1895. Permission to create a 9-hole course on the heath was granted on the condition that male and female club members had equal rights.[253] The course was formally opened on 20 February 1897;[254] the clubhouse was completed shortly afterwards, but was extensively remodelled in 1969.[255]

The 18-hole Reigate Hill Golf Club course was laid out as a par 72 course by the designer, David Williams.[256][257] The club, at Gatton Bottom, was officially opened in November 1995 by professional golfers David Gilford and Andrew Murray.[258]

Rugby Union

Old Reigatian R.F.C. was founded in 1927. Initially the club played its home games at St Alban's Road, but after one year it relocated to Home Farm, Merstham. It moved to its current ground on Park Lane in 1946 and the current clubhouse opened in 2012. As of 2022, the 1st XV plays in the London Two South West League.[259]

Notable buildings and landmarks

Cranston Library

The Cranston Library was opened in 1701 and is the oldest public lending library in England.[260] [261] It was intended primarily for the use of the clergy of the Archdeaconry of Ewell, but its remit was expanded in 1708, to maintain a collection of books "for the use and perusal of the Freeholders, Vicar and Inhabitants" of Reigate Parish "and of the Gentlemen and Clergymen inhabiting parts thereunto adjacent."[262] The library is named after its founder, Andrew Cranston who was the Vicar of Reigate from 1697 to 1708. It is housed on the first floor of the vestry of the Church of St Mary Magdalene. The collection includes over 2000 books, most of which date from the 17th and 18th centuries.[260][261]

Town Hall

The current town hall was completed in 1901 to replace the old town hall in the High Street. It was designed by Macintosh and Newman in the Arts and Crafts style[170] and was originally known as the Municipal Buildings.[263] On opening, it also housed the police station and courts, but the police moved to new premises in Reigate Road in 1943[264] and the courts service vacated the building in the early 1970s.[265] The town hall has been the headquarters of Reigate and Banstead Borough Council, since its inception on 1 April 1974.[52]

Old Town Hall

The old town hall, at the east end of the High Street, was constructed in around 1728.[266] It was built on the site of a chapel, dedicated to St Thomas Becket that was existence before 1330. Following the Reformation, the chapel became a market house. It was demolished in around 1785 and was replaced by the current red brick structure.[267] The building served as the headquarters of Reigate Municipal Borough Council from its formation in 1863[268] until the borough council moved to the new town hall in Castlefield Road in 1901.[269] Randal Vogan purchased the old town hall in 1922 and presented it to the Borough Council.[270][note 25]

Reigate Fort

Reigate Fort, on Reigate Hill, is one of 13 London Defence Positions, built in the 1890s.[271] They were primarily designed as infantry redoubts, to be used in the event of an invasion by the French. The Reigate Fort was completed in 1898 and is one of the largest in the 72 mi (116 km) defensive line. It was defended by an earth rampart and had a clear view south over Reigate. Among the surviving buildings is a magazine, which would have been used for storing ammunition.[272][273] Reigate Fort was declared redundant in 1907 and the land was sold. During the First World War, it was used as an ammunition store and is thought to have been used as a communications station for the British Army South East Command in the Second World War.[274] The fort was restored in the early 2000s and is open to the public.[275][276]

Reigate Hill Footbridge

Reigate Hill Footbridge carries the North Downs Way over the A217 to the north of the town. It was completed in 1910 and has a span of 97 ft (30 m). It was built using the Hennebique method of construction and is one of the earliest reinforced concrete bridges in England.[277] It replaced an earlier chain suspension bridge, which was built in 1825.[191][278]

Wray Common Windmill

Wray Common Windmill was built in 1824 and is to the northeast of the town centre. It is a tower mill constructed of tarred bricks with a metal cap.[279] The mill was used to grind corn until 1895, when it became an agricultural store. It was converted into a four-storey private residence in the 1960s. The building underwent a programme of restoration between 2004 and 2007, which included the installation of new, non-functioning sails.[280]

Parks and open spaces

Castle Gardens were laid out in the 1870s and cover an area of about 2.0 ha (5 acres). They were leased to the Borough Council by Lord Somers in 1873, but the freehold was not acquired by the council until 1921.[57] A stone pyramid on top of the motte acts as a sally port to the Barons' Cave below.[281][282]

Colley Hill, to the northwest of the town, is part of the North Downs escarpment. 1.0 ha (2.5 acres) were donated to the borough council in 1910 and the remainder was purchased by the National Trust in 1913.[283][284] The Inglis Memorial, originally a drinking fountain for horses, was given to the Borough of Reigate by Robert Inglis in 1909.[285] The ceiling of the memorial is decorated with an ornate blue and gold mosaic.[286]

Lower Gatton Park, around 1.9 mi (3 km) north of Reigate, is a 234 ha (580-acre) area of parkland on the south-facing lower slopes of the North Downs. It has its origins as a medieval deer park, which was created from the demesne lands of the manor of Gatton. It was landscaped by Capability Brown in the 1760s and 1770s and includes an 11 ha (27-acre) ornamental lake.[287] The park is open to the public on the first Sunday of each month from February to October.[288]

The southern part of Priory Park was purchased by Randal Vogan in 1920, who donated the land to the Borough Council "to be preserved in its natural beauty for the use and quiet enjoyment of the public".[77][note 25] The remainder of the 58 ha (140-acre) priory grounds were acquired by the borough council in 1948.[78] In 2007, the Borough Council began a restoration project, partly funded by a £4.2M lottery grant.[289] The pavilion, designed by the architect, Dominique Perrault, was constructed as part of the project and houses a cafe.[290][291] The park offers a children's play area, tennis courts and a skate park, as well as walking trails, formal gardens and a lake.[292]

Reigate Heath is a 65 ha (160-acre) Site of Special Scientific Interest to the west of the town centre. The primary habitats are open heath and acid grassland, where the dominant species are common heather, bell heather and wavy hair-grass. Petty whin, soft trefoil and bird's-foot fenugreek are also found in these areas. The site also includes Alder woodland, home to species such as the common bluebell, marsh violet, marsh pennywort and the rare white sedge. At the eastern edge of the heath is an area of marshy meadow, a habitat not found elsewhere in Surrey, which supports meadowsweet, wild angelica, marsh marigolds and the southern marsh orchid.[293]

South Park, to the west of Woodhatch, is a 4.25 ha (10.5-acre) recreation ground managed by the South Park Sports Association. Facilities include sports pitches and a children's playground.[294] A new pump track for mountain bike and BMX riders, funded by two £20,000 grants, was opened in December 2021.[295] The park has been protected by the Fields in Trust charity since October 1934.[294]

Notable people

- John Foxe (1516/17–1587) - martyrologist, worked at Reigate Castle as tutor to the Earl of Surrey's children c. 1548–1559[296]

- John Parsons (1639–1717) - businessman and politician, Lord Mayor of London in 1703, lived at Reigate Priory from 1681 until his death[71][72]

- Ann Alexander (1774/5–1861) - banker, lived for much of her life in Reigate[297]

- George William Alexander (1802–1890) - banker, philanthropist, son of Ann Alexander, lived at Woodhatch from 1853 until his death[298]

- William Harrison Ainsworth (1805–1882) - historical novelist, lived at Reigate for the latter part of his life[299]

- George Luxford (1807–1854) - botanist, lived in Reigate until 1834, published Flora of the Neighbourhood of Reigate in 1838[300]

- Anne Manning (1807–1879) - novelist, lived at Reigate Hill from 1850 to 1878[301]

- James Cudworth (1817–1899) - railway engineer, lived in Reigate from 1879 to 1899[302]

- Francis Frith (1822–1898) - photographer, founded his publishing company in Reigate in 1860[303]

- Edward Frankland (1825–1899) - organometallic chemist, set up his own independent laboratory on Reigate Hill in 1885[304]

- Margaret Crosfield (1859–1952) - geologist, lived for the majority of her life in the town[305]

- Edward Ayearst Reeves (1862–1945) - geographer, died in his Reigate home[306]

- Fred Streeter (1879–1975) - horticulturalist and broadcaster, took his first job at Reigate Hill at the age of 12 and worked in the town until 1897[307]

- H. M. Bateman (1887–1970) - cartoonist and illustrator, lived in Reigate for 14 years from 1918[308]

- Cliff Michelmore (1919–2016) - broadcaster, lived in Reigate for much of his working life[309]

- Bob Doe (1920–2010) - Battle of Britain flying ace, born in Reigate[310][311]

- Ray Alan (1930–2010) - ventriloquist and writer, lived in Reigate towards the end of his life[312][313]

- Max Chilton (b. 1991) - racing driver, was born in Reigate[314] and attended Reigate St Mary's School[315]

Notes

- The name "Wray Common" is thought to derive from the Old English (at)theree meaning "(at) the stream".[7]

- Roman tiles originating from Reigate have been found in London. It is probable that ceramics were transported to markets in Londinium via Stane Street or the London to Brighton Way to the west and east of the town. The nearest points on the two Roman roads to the Doods Road tilery are around 5.6 mi (9 km) distant.[35]

- Each plough team was capable of cultivating 120 acres (49 ha) per year, giving a total area of 14.1 km2 (3,480 acres) of arable land in Reigate in 1086.[39]

- The division of Reigate parish into two distinct administrative areas is unusual among Surrey towns.[49]

- Buckland and Nutfield were transferred to Mole Valley and Tandridge Districts respectively.

- Local legend says that part of Magna Carta was drafted in the Barons' Cave beneath Reigate Castle in 1215, but the academic consensus is that this story is untrue.[55] The earliest recorded reference to the cave system is from 1586.[56]

- In late Victorian times, the field to the east of the castle was used as a cricket pitch.[57] A new road, Castlefield Road, was constructed over the field and the Municipal Buildings were built on the west side, opening in 1901.[58]

- The fifth Earl's parents, Hamelin and Isabel de Warenne had previously presented Reigate Church to the Augustinian Priory of St Mary Overie in Southwark.[62]

- From the 1190s until at least 1291, St Martin's Church in Dorking paid an annual pension of £6 to Lewes Priory in East Sussex.[65]

- Later grants to Reigate Priory include land in Burstow[64] and Westhumble, as well as the advowson of St Michael's Church, Mickleham.[63]

- The chancel at the east end of the priory church became the Howards' private chapel.[68]

- John Parsons was typical of several London businessmen who had experienced the Great Plague of 1665–66 and who chose to move their residences out of the city.[73]

- During the middle ages, goods were generally transported using packhorses, rather than wheeled carts.[81]

- In the medieval and early modern periods, Kingston upon Thames acted as a "port" for much of east Surrey, from where goods could be distributed via the Thames to London and elsewhere.[82]

- In 1466, Richard Jay of Crawley left money in his will to fund repairs to "the weies [ways] of the new causey [causeway] between Crawlei and Reygate".[84]

- On opening, the turnpike over Reigate Hill was so steep that coach passengers had alight and to ascend on foot. In the early 19th century, the base of the cutting was lowered to reduce the gradient[90] and bends in the road were straightened in 1825.[91]

- Reigate railway station was known as Reigate Town until 1898.[98]

- 16th and 17th century documents indicate that hops were grown in the local area by smallholders and that flax was important as a secondary crop. There is no surviving record of rye being cultivated in Reigate.[104]

- Between July and October 1760, approximately 400 visitors to Brighton passed through Reigate, rising to 2000 over the same period in 1787 and between 12,000 and 15,000 in Summer 1811.[114]

- Glovers Road is named after Ambrose Glover, a leaseholder of the land before it was developed.[117]

- Canadian servicemen were injured in September 1940, when two bombs fell at the junction of Evesham Road and West Street.[142]

- The Colley Hill Water Tower was built in 1911 by the Sutton District Water Company, following its acquisition of the Kingswood and District Water Company.[163]

- The statue marks the site of the house, where Fonteyn was born in 1919.[245]

- Thomas White, the batsman responsible for the so-called "wide bat controversy" at a 1771 match between Chertsey and the Hambledon Club, is thought to have lived in Reigate for much of his life.[251]

- Randal Vogan's generosity to Reigate is commemorated in two local street names: Randal Crescent and Vogan Close.[77]

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Reigate Built-up area sub division (1119884973)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Gover, Mawer & Stenton 1934, pp. 281–282

- Robert, Poulton (1980). "Cherchefelle and the origins of Reigate" (PDF). London Archaeologist. 3 (16): 433–436. doi:10.5284/1070630. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Gover, Mawer & Stenton 1934, pp. 304–305

- Ekwall 1963, p. 384

- Camden 1637, p. 296

- Gover, Mawer & Stenton 1934, p. 306

- Hooper 1979, pp. 209–210

- Aubrey 1719, p. 402

- Hooper 1979, p. 149

- "About Reigate". Reigate College. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- "Reigate Conservation Area appraisal" (PDF). Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. February 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- "Mole Abstraction licensing strategy". Environment Agency. 2013. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 47

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 51

- Dines et al. 1933, pp. 11–13

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 77

- Dines et al. 1933, pp. 80–82

- Gallois & Edmunds 1965

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 37

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 179

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 177

- Michette M, Viles H, Vlachou C, Angus I (2020). "The many faces of Reigate Stone: an assessment of variability in historic masonry based on Medieval London's principal freestone". Heritage Science. 8: 80. doi:10.1186/s40494-020-00424-w.

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 100

- Dines et al. 1933, p. 180

- Maslin, Simon (3 April 2020) [4 September 2019]. "Barbed and tanged arrowhead". The Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Hooper, Wilfrid (1937). "A palaeolith from Surrey". The Antiquaries Journal. 17 (3): 318. doi:10.1017/S0003581500094403. S2CID 164049561.

- Hooper 1979, p. 13

- Williams, David (February 2012). "A Bronze Age gold penannular ring from Reigate" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin. 431: 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Williams, David (March 1994). "A late Bronze Age spearhead from Priory Park, Reigate" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin. 282: 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Hooker, Rose; English, Judie (October 2010). "Reigate Heath Archaeological Survey" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin. 425: 17–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- "Roman tile kiln excavated at Doods Road Reigate". Surrey County Council. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- Masefield, Robert (March 1994). "New evidence for a Roman tilery at Reigate in Surrey" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin. 282: 17–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Robertson, Jane (June 2003) [March 2001]. "Extensive Urban Survey of Surrey: Reigate" (PDF). Surrey County Archaeological Unit. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Williams, David (February 2011). "A Roman site at Slipshatch Road, Reigate" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Bulletin. 425: 8–9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Hooper 1979, pp. 22

- Poulton, Robert (1986). "Excavations on the site of the Old Vicarage, Church Street, Reigate, 1977-82, Part I Saxo-Norman and earlier discoveries" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 77: 17–94. doi:10.5284/1069111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Hooper 1979, pp. 20–21

- "Surrey Domesday Book". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- Powell-Smith A (2011). "Reigate". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "A Vision of Britain: First mention of Redhill, units and statistics". University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015.

- "Parliamentary changes under the New Reform Act". Birmingham Daily Post. No. 3089. 15 June 1968. p. 5.

- "Redistribution of Seats Act 1885". No. (48 & 49 Vic. c. 23) of 25 June 1885. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- O'Connell, M (1977). "Historic Towns in Surrey" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Research Volumes. 5: 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Norfolk, Earls and Dukes of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 744.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Arundel, Earls of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 706–709.

- Kümin 1996, pp. 250–255

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 4–5

- Hooper 1979, pp. 180–181

- Hooper 1979, p. 190

- Reigate_&_Banstead_Guide 1989, p. 33

- Historic England. "Reigate Castle Gateway (Grade II) (1188787)". National Heritage List for England.

- Hooper 1979, p. 44

- Douglas 2016, p. 15

- "Barons' Cave, Reigate". The Time Chamber. 2022. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Hooper 1979, pp. 46–47

- Hooper 1979, p. 189

- "Reigate Caves". Wealden Cave and Mine Society. 2021. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Capper, Ian (29 May 2009). "TQ2449: Priory Pond". Geograph. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- Historic England. "Reigate Priory (Grade I) (1188089)". National Heritage List for England.

- Ward 1998, pp. 11–12

- Hooper 1979, pp. 68–69

- Ward 1998, pp. 13–14

- Blair, J (1980). "The Surrey endowments of Lewes Priory before 1200" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 72: 97–126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Hooper 1979, p. 71

- Moore, Alan (27 December 2006). "Reigate Priory and its owners". Redhill and Reigate Life. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Ward 1998, pp. 21–22

- Ward 1998, pp. 24–25

- Ward 1998, pp. 28–29

- Hooper 1979, p. 73

- Moore, Alan (23 January 2007). "Gates were too close to a pub". Redhill and Reigate Life. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Ward 1998, p. 32

- Hooper 1979, pp. 73–74

- Ward 1998, p. 44

- Ward 1998, pp. 63–65

- Ward 1998, pp. 86–87

- "Ministerial sanction for £19,120 loan for Priory purchase and £7,000 grant". Surrey Mirror. No. 3665. 7 May 1948. p. 7.

- Ward 1998, pp. 106–107

- Ward 1998, pp. 114–115

- Greenwood 2008, p. 7

- Greenwood 2008, p. 52

- Hooper 1979, pp. 82–83

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 23–24

- Greenwood 2008, p. 23

- Hooper 1979, p. 85

- Greenwood 2008, p. 26

- Hooper 1979, pp. 86–87

- Greenwood 2008, p. 32

- Greenwood 2008, p. 29

- Greenwood 2008, p. 33

- Hooper 1979, p. 90

- Ward 1998, pp. 51–52

- Historic England. "The Tunnel (Grade II) (1241366)". National Heritage List for England.

- Hooper 1979, p. 91

- Hooper 1979, p. 177

- Jackson 1988, p. 7

- Mitchell & Smith 1989, Fig. 97

- "Southern Railway Developments". The Times. No. 45724. London. 19 January 1931. p. 9.

- Asher 2018, p. 115

- Petty, John (5 October 1985). "Cracked M25 link to open". Daily Telegraph. No. 40526. London. p. 36.

- Hooper 1979, p. 40

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 52–53

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 10–11

- Greenwood 2008, p. 16

- Hooper 1979, pp. 25–26

- Hooper 1979, pp. 77

- Hooper 1979, p. 96

- Farries & Mason 1966, pp. 184–188

- Farries & Mason 1966, pp. 191–193

- Farries & Mason 1966, pp. 179–180

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 65–66

- Greenwood 2008, p. 57

- Greenwood 2008, pp. 38–39

- Hooper 1979, pp. 178–179

- Hooper 1979, pp. 182–183

- Ingram & Pendrill 1982, p. 51

- Lovell, Cara (4 August 2004). "Rediscover the Great Doods". Redhill and Reigate Life. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Moore, Alan (9 March 2007). "A lady not partial to a drink". Redhill and Reigate Life. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Capper, Ian (28 November 2009). "TQ2548: Western Parade, Woodhatch". Geograph. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Powell 2000a, pp. 71–72

- Hooper 1979, pp. 144–146

- Butt, C.R. (1959). "Surrey and the Civil War". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 37 (149): 13–20. JSTOR 44226916.

- Ingram 1992, p. 46

- Ingram 1992, p. 49

- Mitchell & Smith 1989, Fig. 99

- "Hillfield Red Cross Hospital". Lost Hospitals of London. May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "The Croft Home". Lost Hospitals of London. November 2009. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Ingram 1992, pp. 56–57

- "The Beeches Auxiliary Military Hospital". Lost Hospitals of London. May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Slaughter 2004, pp. 98–99

- Ogley 1995, p. 25

- Pilkington 1997, p. 196

- Ogley 1995, p. 89

- Harding 1998, p. 26

- Powell 2000a, p. 71

- Ogley 1995, p. 171

- Crook 2000, p. 25

- Crook 2000, p. 69

- Crook 2000, p. 71

- Ogley 1995, p. 144

- Harding 1998, p. 100

- "Reigate Hill WW2 plane crash memorial unveiled". BBC News. London. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "Reigate". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- "Sir George Gardiner". The Times. No. 67611. London. 18 November 2002. p. 28.

- Garnett, Mark (6 January 2011). "Gardiner, Sir George Arthur (1935–2002), journalist and politician". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/77387. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Riddle, Peter (10 January 2019). "Howe, (Richard Edward) Geoffrey, Baron Howe of Aberavon (1926–2015), politician". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.110802. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Armstrong, Julie (15 October 2020). "Surrey County Council set to be based in Surrey for first time in 55 years". Surrey Live. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Armstrong, Julie (24 December 2020). "After 127 years, County Council finally moves back into Surrey". Guildford Dragon. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "List of County Councillors". Surrey County Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Victor Lewanski". Surrey County Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Catherine Baart". Surrey County Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Boundary review: council wants fewer councillors, larger wards". reigate.uk. 8 January 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Michael Blacker". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Victor Lewanski". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Kate Fairhurst". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "James King". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Paul Chandler". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Andrew Proudfoot". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- Drapans, Will (17 April 2015). "Town Twinning". Reigate & Banstead Borough Council. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- Crocker 1999, p. 75

- Hooper 1979, p. 176

- Capper, Ian (1 February 2009). "Colley Hill Water Tower". Geograph. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Hooper 1979, pp. 181–182

- Tarplee, Peter (2007). "Some public utilities in Surrey: Electricity and gas" (PDF). Surrey History. 7 (5): 262–272. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Capper, Ian (12 April 2021). "TQ2650: Former Reigate Corporation Electricity Works". UK Geograph. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Crocker 1999, p. 118

- Moore, Alan. "The Borough of Reigate Police Force". Redhill & Reigate History. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Hooper 1979, p. 174

- Historic England. "Town Hall (1260489)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- Moore & Chinery 2003, p. 44

- "Reigate Old Fire Station". Fire Stations. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- "Our Fire Station". Surrey County Council. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "Our Locations". South East Coast Ambulance Service. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "Results for Hospitals in Reigate". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "GPs near Reigate". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- "World Airline Directory". Flight International. 26 July 1980. 274 Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine. "Head Office: Europe House, Bancroft Road, Reigate, Surrey, Great Britain."

- Capper, Ian (4 April 2015). "The Observatory". UK Geograph. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- "Canon UK". Canon. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Richmond in Surrey David Richmond + Partners' headquarters building for Canon in Reigate draws inspiration from an existing Regency villa to create a contemporary office complex with classical proport". Architects' Journal. 9 March 2000. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Locations". Kimberly Clark. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Benefits Practice Summer Intern". Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Arnot, Chris (30 October 1994). "Small brewers droop in the face of pub monopoly". The Observer. No. 10594. p. 8.

- Seymour, Jenny (11 November 2013). "Reigate's Pilgrim Brewery comes of age after 30-year battle for survival". thisissurrey.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Reigate". Southern Railway. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "East Surrey, Horley and Redhill bus timetables". Surrey County Council. 15 September 2020. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Reigate, Redhill and Merstham buses" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "The Surrey Cycleway" (PDF). Surrey County Council. 7 July 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "The Greensand Way long distance route". Surrey County Council. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "The Greensand Way" (PDF). Surrey County Council. 12 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Curtis & Walker 2007, pp. 55–57

- "Dovers Green School". Greensand Multi-Academy Trust. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- "Wray Common Primary School". Greensand Multi-Academy Trust. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- Seymour, Jenny (11 December 2017). "All you need to know about the forest school opening in Redhill's old law courts next September". Surrey Live. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- Goss 1995, p. 85

- Seymour, Jenny (20 December 2020). "Deteriorating Reigate Priory 'could be wedding venue, library, museum or posh restaurant'". Surrey Live. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- "Reigate School". Greensand Multi-Academy Trust. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- "Woodhatch School opening in September". Surrey Mirror. No. 4273. 20 June 1958. p. 5.

- Clarke 2005, p. 3

- "School Timeline". Royal Alexandra & Albert School. 2021. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Clarke 2005, p. 35

- "School Overview". Royal Alexandra & Albert School. 2021. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Royal Alexandra and Albert School". Ofsted. 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Why choose Reigate College?". Reigate College. 2019. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Reigate_College_Prospectus 1985, p. 5

- Goss 1995, p. 81

- Capper, Ian (16 May 2009). "Reigate College". UK Geograph. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- "History". Micklefield School. 2021. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "Welcom". Micklefield School. 2021. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "History & Tradition". Reigate St Mary's. 24 September 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "Welcome to Reigate St Mary's". Reigate St Mary's. 17 September 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "History & Tradition". Reigate Grammar School. 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "Our History & Future". Dunottar School. April 2021. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- Historic England. "Dunottar School (High Trees) (Grade II) (1260767)". National Heritage List for England.

- "FAQs". Dunottar School. 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- "South East Surrey Short Stay School becomes Reigate Valley College". surreymirror.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Welcome". Brooklands School. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "Moon Hall School". Moon Hall School. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- Malden 1911, pp. 229–245

- Hooper 1979, pp. 50–51