Retail

Retail is the sale of goods and services to consumers, in contrast to wholesaling, which is sale to business or institutional customers. A retailer purchases goods in large quantities from manufacturers, directly or through a wholesaler, and then sells in smaller quantities to consumers for a profit. Retailers are the final link in the supply chain from producers to consumers.

Retail markets and shops have a very ancient history, dating back to antiquity. Some of the earliest retailers were itinerant peddlers. Over the centuries, retail shops were transformed from little more than "rude booths" to the sophisticated shopping malls of the modern era. In the digital age, an increasing number of retailers are seeking to reach broader markets by selling through multiple channels, including both bricks and mortar and online retailing. Digital technologies are also affecting the way that consumers pay for goods and services. Retailing support services may also include the provision of credit, delivery services, advisory services, stylist services and a range of other supporting services. Retail workers are the employees of such stores.

Most modern retailers typically make a variety of strategic level decisions including the type of store, the market to be served, the optimal product assortment, customer service, supporting services, and the store's overall market positioning. Once the strategic retail plan is in place, retailers devise the retail mix which includes product, price, place, promotion, personnel, and presentation.

Etymology

The word retail comes from the Old French verb tailler, meaning "to cut off, clip, pare, divide in terms of tailoring" (c. 1365). It was first recorded as a noun in 1433 with the meaning of "a sale in small quantities" from the Middle French verb retailler meaning "a piece cut off, shred, scrap, paring".[1] At the present, the meaning of the word retail (in English, French, Dutch, German and Spanish) refers to the sale of small quantities of items to consumers (as opposed to wholesale).

Definition and explanation

Retail refers to the activity of selling goods or services directly to consumers or end-users.[2] Some retailers may sell to business customers, and such sales are termed non-retail activity. In some jurisdictions or regions, legal definitions of retail specify that at least 80 per cent of sales activity must be to end-users.[3]

Retailing often occurs in retail stores or service establishments, but may also occur through direct selling such as through vending machines, door-to-door sales or electronic channels.[4] Although the idea of retail is often associated with the purchase of goods, the term may be applied to service providers that sell to consumers. Retail service providers include retail banking, tourism, insurance, private healthcare, private education, private security firms, legal firms, publishers, public transport, and others. For example, a tourism provider might have a retail division that books travel and accommodation for consumers plus a wholesale division that purchases blocks of accommodation, hospitality, transport, and sightseeing which are subsequently packaged into a holiday tour for sale to retail travel agents.

Some retailers badge their stores as "wholesale outlets" offering "wholesale prices." While this practice may encourage consumers to imagine that they have access to lower prices, while being prepared to trade-off reduced prices for cramped in-store environments, in a strictly legal sense, a store that sells the majority of its merchandise direct to consumers, is defined as a retailer rather than a wholesaler. Different jurisdictions set parameters for the ratio of consumer to business sales that define a retail business.

History

Retail markets have existed since ancient times. Archaeological evidence for trade, probably involving barter systems, dates back more than 10,000 years. As civilizations grew, barter was replaced with retail trade involving coinage. Selling and buying are thought to have emerged in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) in around the 7th-millennium BCE.[5] In ancient Greece, markets operated within the agora, an open space where, on market days, goods were displayed on mats or temporary stalls.[6] In ancient Rome, trade took place in the forum.[7] The Roman forum was arguably the earliest example of a permanent retail shop-front.[8] Recent research suggests that China exhibited a rich history of early retail systems.[9] From as early as 200 BCE, Chinese packaging and branding were used to signal family, place names and product quality, and the use of government imposed product branding was used between 600 and 900 CE.[10] Eckhart and Bengtsson have argued that during the Song Dynasty (960–1127), Chinese society developed a consumerist culture, where a high level of consumption was attainable for a wide variety of ordinary consumers rather than just the elite.[11] In Medieval England and Europe, relatively few permanent shops were to be found; instead, customers walked into the tradesman's workshops where they discussed purchasing options directly with tradesmen.[12] In the more populous cities, a small number of shops were beginning to emerge by the 13th century.[13] Outside the major cities, most consumable purchases were made through markets or fairs.[14] Market-places appear to have emerged independently outside Europe. The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is often cited as the world's oldest continuously operating market; its construction began in 1455. The Spanish conquistadors wrote glowingly of markets in the Americas. In the 15th century, the Mexica (Aztec) market of Tlatelolco was the largest in all the Americas.[15]

By the 17th century, permanent shops with more regular trading hours were beginning to supplant markets and fairs as the main retail outlet. Provincial shopkeepers were active in almost every English market town.[16] As the number of shops grew, they underwent a transformation. The trappings of a modern shop, which had been entirely absent from the sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century store, gradually made way for store interiors and shopfronts that are more familiar to modern shoppers. Prior to the eighteenth century, the typical retail store had no counter, display cases, chairs, mirrors, changing rooms, etc. However, the opportunity for the customer to browse merchandise, touch and feel products began to be available, with retail innovations from the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[17]

%252C_au_Palais-Royal%252C_1825.jpg.webp)

By the late 18th century, grand shopping arcades began to emerge across Europe and in the Antipodes. A shopping arcade refers to a multiple-vendor space, operating under a covered roof. Typically, the roof was constructed of glass to allow for natural light and to reduce the need for candles or electric lighting. Some of the earliest examples of shopping arcade appeared in Paris, due to its lack of pavement for pedestrians.[18] While the arcades were the province of the bourgeoisie, a new type of retail venture emerged to serve the needs of the working poor. John Stuart Mill wrote about the rise of the co-operative retail store, which he witnessed first-hand in the mid-nineteenth century.[19]

The modern era of retailing is defined as the period from the industrial revolution to the 21st century.[20] In major cities, the department store emerged in the mid- to late 19th century, and permanently reshaped shopping habits, and redefined concepts of service and luxury.[21] Many of the early department stores were more than just a retail emporium; rather they were venues where shoppers could spend their leisure time and be entertained.[22] Retail, using mail order, came of age during the mid-19th century. Although catalogue sales had been used since the 15th century, this method of retailing was confined to a few industries such as the sale of books and seeds. However, improvements in transport and postal services led several entrepreneurs on either side of the Atlantic to experiment with catalogue sales.[23]

In the post-war period, an American architect, Victor Gruen developed a concept for a shopping mall; a planned, self-contained shopping complex complete with an indoor plaza, statues, planting schemes, piped music, and car-parking. Gruen's vision was to create a shopping atmosphere where people felt so comfortable, they would spend more time in the environment, thereby enhancing opportunities for purchasing. The first of these malls opened at Northland Mall near Detroit in 1954.[24] Throughout the twentieth century, a trend towards larger store footprints became discernible. The average size of a U.S. supermarket grew from 31,000 square feet (2,900 m2) square feet in 1991 to 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2) square feet in 2000.[25] By the end of the twentieth century, stores were using labels such as "mega-stores" and "warehouse" stores to reflect their growing size.[26] The upward trend of increasing retail space was not consistent across nations and led in the early 21st century to a 2-fold difference in square footage per capita between the United States and Europe.[27]

As the 21st century takes shape, some indications suggest that large retail stores have come under increasing pressure from online sales models and that reductions in store size are evident.[28] Under such competition and other issues such as business debt,[29] there has been a noted business disruption called the retail apocalypse in recent years which several retail businesses, especially in North America, are sharply reducing their number of stores, or going out of business entirely.

Retail strategy

The distinction between "strategic" and "managerial" decision-making is commonly used to distinguish "two phases having different goals and based on different conceptual tools. Strategic planning concerns the choice of policies aiming at improving the competitive position of the firm, taking account of challenges and opportunities proposed by the competitive environment. On the other hand, managerial decision-making is focused on the implementation of specific targets."[30]

In retailing, the strategic plan is designed to set out the vision and provide guidance for retail decision-makers and provide an outline of how the product and service mix will optimize customer satisfaction. As part of the strategic planning process, it is customary for strategic planners to carry out a detailed environmental scan which seeks to identify trends and opportunities in the competitive environment, market environment, economic environment and statutory-political environment. The retail strategy is normally devised or reviewed every three to five years by the chief executive officer. The profit margins of retailers depend largely on their ability to achieve market competitive transaction costs.

The strategic retail analysis typically includes following elements:[31]

- Market analysis – Market size, stage of market, market competitiveness, market attractiveness, market trends

- Customer analysis – Market segmentation, demographic, geographic, and psychographic profile, values and attitudes, shopping habits, brand preferences, analysis of needs and wants, and media habits

- Internal analysis – Other capacities including human resource capability, technological capability, financial capability, ability to generate scale economies or economies of scope, trade relations, reputation, positioning, and past performance

- Competition analysis – Availability of substitutes, competitor's strengths and weaknesses, perceptual mapping, competitive trends

- Review of product mix – :: Sales per square foot, stock-turnover rates, profitability per product line

- Review of distribution channels – Lead-times between placing order and delivery, cost of distribution, cost efficiency of intermediaries

- Evaluation of the economics of the strategy – Cost-benefit analysis of planned activities

At the conclusion of the retail analysis, retail marketers should have a clear idea of which groups of customers are to be the target of marketing activities. Not all elements are, however, equal, often with demographics, shopping motivations, and spending directing consumer activities.[32] Retail research studies suggest that there is a strong relationship between a store's positioning and the socio-economic status of customers.[33] In addition, the retail strategy, including service quality, has a significant and positive association with customer loyalty.[34] A marketing strategy effectively outlines all key aspects of firms' targeted audience, demographics, preferences. In a highly competitive market, the retail strategy sets up long-term sustainability. It focuses on customer relationships, stressing the importance of added value, customer satisfaction and highlights how the store's market positioning appeals to targeted groups of customers.[35]

Retail marketing

A retail mix is devised for the purpose of coordinating day-to-day tactical decisions. The retail marketing mix typically consists of six broad decision layers including product decisions, place decisions, promotion, price, personnel and presentation (also known as physical evidence). The retail mix is loosely based on the marketing mix, but has been expanded and modified in line with the unique needs of the retail context. A number of scholars have argued for an expanded marketing, mix with the inclusion of two new Ps, namely, Personnel and Presentation since these contribute to the customer's unique retail experience and are the principal basis for retail differentiation. Yet other scholars argue that the Retail Format (i.e. retail formula) should be included.[36] The modified retail marketing mix that is most commonly cited in textbooks is often called the 6 Ps of retailing (see diagram at right).[37][38]

The primary product-related decisions facing the retailer are the product assortment (what product lines, how many lines and which brands to carry); the type of customer service (high contact through to self-service) and the availability of support services (e.g. credit terms, delivery services, after sales care). These decisions depend on careful analysis of the market, demand, competition as well as the retailer's skills and expertise.

Customer service is the "sum of acts and elements that allow consumers to receive what they need or desire from [the] retail establishment." Retailers must decide whether to provide a full service outlet or minimal service outlet, such as no-service in the case of vending machines; self-service with only basic sales assistance or a full service operation as in many boutiques and speciality stores. In addition, the retailer needs to make decisions about sales support such as customer delivery and after sales customer care.

Place decisions are primarily concerned with consumer access and may involve location, space utilisation and operating hours. Retailers may consider a range of both qualitative and quantitative factors to evaluate to potential sites under consideration. Macro factors include market characteristics (demographic, economic and socio-cultural), demand, competition and infrastructure (e.g. the availability of power, roads, public transport systems). Micro factors include the size of the site (e.g. availability of parking), access for delivery vehicles. A major retail trend has been the shift to multi-channel retailing. To counter the disruption caused by online retail, many bricks and mortar retailers have entered the online retail space, by setting up online catalogue sales and e-commerce websites. However, many retailers have noticed that consumers behave differently when shopping online. For instance, in terms of choice of online platform, shoppers tend to choose the online site of their preferred retailer initially, but as they gain more experience in online shopping, they become less loyal and more likely to switch to other retail sites.[39] Online stores are usually available 24 hours a day, and many consumers across the globe have Internet access both at work and at home.

The broad pricing strategy is normally established in the company's overall strategic plan. In the case of chain stores, the pricing strategy would be set by head office. Broadly, there are six approaches to pricing strategy mentioned in the marketing literature: operations-oriented,[40] revenue-oriented,[40] customer-oriented,[40] value-based,[41][42] relationship-oriented,[43] and socially-oriented.[44] When decision-makers have determined the broad approach to pricing (i.e., the pricing strategy), they turn their attention to pricing tactics. Tactical pricing decisions are shorter term prices, designed to accomplish specific short-term goals. Pricing tactics that are commonly used in retail include discount pricing,[45] everyday low prices,[46] high-low pricing,[46][47] loss leaders, product bundling,[48] promotional pricing, and psychological pricing.[49] Retailers must also plan for customer preferred payment modes – e.g. cash, credit, lay-by, Electronic Funds Transfer at Point-of-Sale (EFTPOS). All payment options require some type of handling and attract costs.[50] Contrary to common misconception, price is not the most important factor for consumers, when deciding to buy a product.[51]

Because patronage at a retail outlet varies, flexibility in scheduling is desirable. Employee scheduling software is sold, which, using known patterns of customer patronage, more or less reliably predicts the need for staffing for various functions at times of the year, day of the month or week, and time of day. Usually needs vary widely. Conforming staff utilization to staffing needs requires a flexible workforce which is available when needed but does not have to be paid when they are not, part-time workers; as of 2012 70% of retail workers in the United States were part-time. This may result in financial problems for the workers, who while they are required to be available at all times if their work hours are to be maximized, may not have sufficient income to meet their family and other obligations.[52] Retailers can employ different techniques to enhance sales volume and to improve the customer experience, such as Add-on, Upsell or Cross-sell; Selling on value;[53] and knowing when to close the sale.[54]

Transactional marketing aims to find target consumers, then negotiate, trade, and finally end relationships to complete the transaction. In this one-time transaction process, both parties aim to maximize their own interests. As a result, transactional marketing raises follow-up problems such as poor after-sales service quality and a lack of feedback channels for both parties. In addition, because retail enterprises needed to redevelop client relationships for each transaction, marketing costs were high and customer retention was low. All these downsides to transactional marketing gradually pushed the retail industry towards establishing long-term cooperative relationships with customers. Through this lens, enterprises began to focus on the process from transaction to relationship.[55] While expanding the sales market and attracting new customers is very important for the retail industry, it is also important to establish and maintain long term good relationships with previous customers, hence the name of the underlying concept, "relational marketing". Under this concept, retail enterprises value and attempt to improve relationships with customers, as customer relationships are conducive to maintaining stability in the current competitive retail market, and are also the future of retail enterprises.

.jpg.webp)

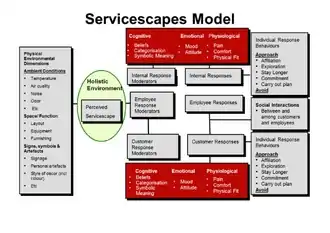

Presentation refers to the physical evidence that signals the retail image. Physical evidence may include a diverse range of elements – the store itself including premises, offices, exterior facade and interior layout, websites, delivery vans, warehouses, staff uniforms. The environment in which the retail service encounter occurs is sometimes known as the retail servicescape.[56] The store environment consists of many elements such as aromas, the physical environment (furnishings, layout, and functionality), ambient conditions (lighting, air temperature, and music) as well as signs, symbols, and artifacts (e.g. sales promotions, shelf space, sample stations, visual communications). Retail designers pay close attention to the front of the store, which is known as the decompression zone. In order to maximize the number of selling opportunities, retailers generally want customers to spend more time in a retail store. However, this must be balanced against customer expectations surrounding convenience, access and realistic waiting times.[57] The way that brands are displayed is also part of the overall retail design. Where a product is placed on the shelves has implications for purchase likelihood as a result of visibility and access.[58] Ambient conditions, such as lighting, temperature and music, are also part of the overall retail environment.[59] It is common for a retail store to play music that relates to their target market.[60]

Shopper profiles

Two different strands of research have investigated shopper behaviour. One is primarily concerned with shopper motivations. The other stream of research seeks to segment shoppers according to common, shared characteristics. To some extent, these streams of research are inter-related, but each stream offers different types of insights into shopper behaviour.

_(14593807460).jpg.webp)

Babin et al. carried out some of the earliest investigations into shopper motivations and identified two broad motives: utilitarian and hedonic. Utilitarian motivations are task-related and rational. For the shopper with utilitarian motives, purchasing is a work-related task that is to be accomplished in the most efficient and expedient manner. On the other hand, hedonic motives refer to pleasure. The shopper with hedonic motivations views shopping as a form of escapism where they are free to indulge fantasy and freedom. Hedonic shoppers are more involved in the shopping experience.[61]

Many different shopper profiles can be identified. Retailers develop customised segmentation analyses for each unique outlet. However, it is possible to identify a number of broad shopper profiles. One of the most well-known and widely cited shopper typologies is that developed by Sproles and Kendal in the mid-1980s.[62][63][64] Sproles and Kendall's consumer typology has been shown to be relatively consistent across time and across cultures.[65][66] Their typology is based on the consumer's approach to making purchase decisions.[67]

- Quality conscious/Perfectionist: Quality-consciousness is characterised by a consumer's search for the very best quality in products; quality conscious consumers tend to shop systematically making more comparisons and shopping around.

- Brand-conscious: Brand-consciousness is characterised by a tendency to buy expensive, well-known brands or designer labels. Those who score high on brand-consciousness tend to believe that the higher prices are an indicator of quality and exhibit a preference for department stores or top-tier retail outlets.

- Recreation-conscious/Hedonistic: Recreational shopping is characterised by the consumer's engagement in the purchase process. Those who score high on recreation-consciousness regard shopping itself as a form of enjoyment.

- Price-conscious: A consumer who exhibits price-and-value consciousness. Price-conscious shoppers carefully shop around seeking lower prices, sales or discounts and are motivated by obtaining the best value for money.

- Novelty/fashion-conscious: characterised by a consumer's tendency to seek out new products or new experiences for the sake of excitement; who gain excitement from seeking new things; they like to keep up-to-date with fashions and trends, variety-seeking is associated with this dimension.

- Impulsive: Impulsive consumers are somewhat careless in making purchase decisions, buy on the spur of the moment and are not overly concerned with expenditure levels or obtaining value. Those who score high on impulsive dimensions tend not to be engaged with the object at either a cognitive or emotional level.

- Confused (by overchoice): characterised by a consumer's confusion caused by too many product choices, too many stores or an overload of product information; tend to experience information overload.

- Habitual/brand loyal: characterised by a consumer's tendency to follow a routine purchase pattern on each purchase occasion; consumers have favourite brands or stores and have formed habits in choosing; the purchase decision does not involve much evaluation or shopping around.

Some researchers have adapted Sproles and Kendall's methodology for use in specific countries or cultural groups.[68] Consumer decision styles are important for retailers and marketers because they describe behaviours that are relatively stable over time and for this reason, they are useful for market segmentation.

Types of retail outlets

Retail formats (also known as retail formulas) influence the consumer's store choice and addresses the consumer's expectations. At its most basic level, a retail format is a simple marketplace, that is; a location where goods and services are exchanged. In some parts of the world, the retail sector is still dominated by small family-run stores, but large retail chains are increasingly dominating the sector, because they can exert considerable buying power and pass on the savings in the form of lower prices. Many of these large retail chains also produce their own private labels which compete alongside manufacturer brands. Considerable consolidation of retail stores has changed the retail landscape, transferring power away from wholesalers and into the hands of the large retail chains.[69] In Britain and Europe, the retail sale of goods is designated as a service activity. The European Service Directive applies to all retail trade including periodic markets, street traders and peddlers.

Retail stores may be classified by the type of product carried. Softline retailers sell goods that are consumed after a single-use, or have a limited life (typically under three years) in they are normally consumed. Soft goods include clothing, other fabrics, footwear, toiletries, cosmetics, medicines and stationery.[70][71] Grocery stores, including supermarkets and hypermarkets, along with convenience stores carry a mix of food products and consumable household items such as detergents, cleansers, personal hygiene products. Retailers selling consumer durables are sometimes known as hardline retailers[72] – automobiles, appliances, electronics, furniture, sporting goods, lumber, etc., and parts for them. Specialist retailers operate in many industries such as the arts e.g. green grocers, contemporary art galleries, bookstores, handicrafts, musical instruments, gift shops.

Challenges

To achieve and maintain a foothold in an existing market, a prospective retail establishment must overcome the following hurdles:

- regulatory barriers including:

- restrictions on real-estate purchases, especially as imposed by local governments and against "big-box" chain retailers

- restrictions on foreign investment in retailers, in terms of both absolute amount of financing provided and percentage share of voting stock (e.g. common stock) purchased

- unfavorable taxation structures, especially those designed to penalize or keep out "big box" retailers (see "Regulatory" above)

- absence of developed supply-chain and integrated IT management

- high competitiveness among existing market participants and resulting low profit margins, caused in part by:

- constant advances in product design resulting in constant threat of product obsolescence and price declines for existing inventory

- lack of a properly-educated and/or -trained work-force, often including management, caused in part by loss in business

- lack of educational infrastructure enabling prospective market entrants to respond to the above challenges

- direct e-tailing (for example, through the Internet) and direct delivery to consumers from manufacturers and suppliers, cutting out any retail middle man.[73]

Method

When discussing the impact of technology on shopping and retail, e-commerce is often the first thing that comes to mind for retailers. However, technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence, computer vision and the Internet of Things have used data to transform every part of the shopping experience, from browsing to checkout.[74]

It is important for organizations to embrace digital disruption in order to gain a competitive advantage. When an industry experiences digital disruption, it typically signals that consumer needs are shifting. Retailers enhance their analytics process and make better informed decisions thanks to big data, artificial intelligence, computer vision, and the Internet of Things. The use of data by retailers is mostly evident in the following aspects, based on the above-mentioned new technologies:

- Enhance marketing by Personalizing customer experience

- Optimize supply chain management

- Adjust prices to maximize profits

Many leading brands choose to target tourists who specifically travel to shop or spend money while on vacation. According to the Global Retail Tourism Market Report 2019-2023,[75] the value of the global shopping tourism market was estimated to be around $1.2 trillion in 2018. The report also forecasts that the market will grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.7% from 2019 to 2023. In 2023 Kogan Page published a critically acclaimed[76] book "Leading Travel and Tourism Retail", which researched in depth the travel retail sector post COVID.

Consolidation

Among retailers and retails chains a lot of consolidation has appeared over the last couple of decades. Between 1988 and 2010, worldwide 40,788 mergers & acquisitions with a total known value of US$2.255 trillion have been announced.[77] The largest transactions with involvement of retailers in/from the United States have been: the acquisition of Albertson's Inc. for US$17 billion in 2006,[78] the merger between Federated Department Stores Inc with May Department Stores valued at 16.5 bil. USD in 2005[79] – now Macy's, and the merger between Kmart Holding Corp and Sears Roebuck & Co with a value of US$10.9 billion in 2004.[80]

Between 1985 and 2018 there have been 46,755 mergers or acquisitions conducted globally in the retail sector (either acquirer or target from the retail industry). These deals cumulate to an overall known value of around US$2,561 billion. The three major Retail M&A waves took place in 2000, 2007 and lately in 2017. However the all-time high in terms of number of deals was in 2016 with more than 2,700 deals. In terms of added value 2007 set the record with the US$225 billion.[81]

Here is a list of the top ten largest deals (ranked by volume) in the Retail Industry:

| Date Announced | Acquiror Name | Acquiror Mid Industry | Acquiror Nation | Target Name | Target Mid Industry | Target Nation | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

| 11/01/2006 | CVS Corp | Other Retailing | United States | Caremark Rx Inc | Healthcare Providers & Services (HMOs) | United States | 26,293.58 |

| 03/09/2007 | AB Acquisitions Ltd | Other Financials | United Kingdom | Alliance Boots PLC | Other Retailing | United Kingdom | 19,604.19 |

| 12/18/2000 | Shareholders | Other Financials | United Kingdom | Granada Compass-Hospitality | Food & Beverage Retailing | United Kingdom | 17,914.68 |

| 01/20/2006 | AB Acquisition LLC | Other Financials | United States | Albertsons Inc | Food & Beverage Retailing | United States | 17,543.85 |

| 02/26/2013 | Home Depot Inc | Home Improvement Retailing | United States | Home Depot Inc | Home Improvement Retailing | United States | 17,000.00 |

| 02/28/2005 | Federated Department Stores | Discount and Department Store Retailing | United States | May Department Stores Co | Non Residential | United States | 16,465.87 |

| 08/30/1999 | Carrefour SA | Food & Beverage Retailing | France | Promodes | Food & Beverage Retailing | France | 15,837.48 |

| 06/19/2012 | Walgreen Co | Other Retailing | United States | Alliance Boots GmbH | Other Retailing | Switzerland | 15,292.48 |

| 07/02/2007 | Wesfarmers Ltd | Food & Beverage Retailing | Australia | Coles Group Ltd | Food & Beverage Retailing | Australia | 15,287.79 |

| 06/03/2011 | Wal-Mart Stores Inc | Discount and Department Store Retailing | United States | Wal-Mart Stores Inc | Discount and Department Store Retailing | United States | 14,288.00 |

Statistics

Global top ten retailers

As of 2016, China was the largest retail market in the world.[82]

| Worldwide top ten retailers[83] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Company | Headquarters | 2020 total revenue (US$ billion)[83] | Business foundation | Number of countries of operation 2020 |

| 1 | Walmart | $519.93 | Hypermarket/supercenter/superstore | 27 | |

| 2 | Amazon | $280.52 | Ecommerce | 18 | |

| 3 | Costco | $163.22 | Cash & carry/warehouse club | 12 | |

| 4 | Schwarz Gruppe (Lidl) | $133.89 | Discount grocery store | 33 | |

| 5 | Aldi | $116.06 | Discount grocery store | 18 | |

| 6 | JD.com | $82.86 | Ecommerce | - | |

| 7 | Carrefour | $82.60 | Hypermarket/supermarket | 32 | |

| 8 | Ahold Delhaize | $78.17 | Grocery store | 10 | |

| 9 | Alibaba | $71.99 | Ecommerce | 7 | |

| 10 | IKEA | $45.18 | Furniture | 60 | |

Statistics for national retail sales

United States

The National Retail Federation and Kantar annually rank the nation's top retailers according to sales.[84] The National Retail Federation also separately ranks the 100 fastest-growing U.S. retailers based on increases in domestic sales.[85][86]

Since 1951, the U.S. Census Bureau has published the Retail Sales report every month. It is a measure of consumer spending, an important indicator of the US GDP. Retail firms provide data on the dollar value of their retail sales and inventories. A sample of 12,000 firms is included in the final survey and 5,000 in the advanced one. The advanced estimated data is based on a subsample from the US CB complete retail & food services sample.[87]

Retail is the largest private-sector employer in the United States, supporting 52 million working Americans.[88]

Central Europe

In 2011, the grocery market in six countries of Central Europe was worth nearly €107bn, 2.8% more than the previous year when expressed in local currencies. The increase was generated foremost by the discount stores and supermarket segments, and was driven by the skyrocketing prices of foodstuffs. This information is based on the latest PMR report entitled Grocery retail in Central Europe 2012[89]

World

National accounts show a combined total of retail and wholesale trade, with hotels and restaurants. in 2012 the sector provides over a fifth of GDP in tourist-oriented island economies, as well as in other major countries such as Brazil, Pakistan, Russia, and Spain. In all four of the latter countries, this fraction is an increase over 1970, but there are other countries where the sector has declined since 1970, sometimes in absolute terms, where other sectors have replaced its role in the economy. In the United States the sector has declined from 19% of GDP to 14%, though it has risen in absolute terms from $4,500 to $7,400 per capita per year. In China the sector has grown from 7.3% to 11.5%, and in India even more, from 8.4% to 18.7%. Emarketer predicts China will have the largest retail market in the world in 2016.[90]

In 2016, China became the largest retail market in the world.[82]

In the Republic of Armenia, retail trade has been increasing recently. In October 2022, it increased by 23.1% year by year, which was the most considerable rise since April 2021, faster than the 20.7 per cent increase recorded a month earlier. Retail dropped by 1.9% after accumulating 2.1%in the earlier month. For the first 10 months of 2022, retail sales increased by 15.5% by measuring the exact time of 2021. Among its bordering countries, on retail trade percentage of GDP, Armenia ranks more increased than Turkey, but it is still lower than Georgia.[91]

See also

- Automated retail

- Direct-to-consumer

- Business-to-business

- B2G

- Consumer behaviour

- Department store

- Final goods

- Grey pound

- Hanseatic League

- High Street

- History of marketing

- Like for like

- List of department stores by country

- Point of sales

- Sales promotion

- Retail concentration

- Retail design

- Retail software

- Retailtainment

- Revenge buying

- Sales density

- Shelving engineering

- Shopping

- Store manager

- Visual merchandising

- Licensed victualler

- Wardrobing

- Window shopping

References

- Harper, Douglas. "retail". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "retail". Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2018 – via The Free Dictionary.

- Pride, W.M., Ferrell, O.C. Lukas, B.A., Schembri, S. Niininen, O. and Cassidy, R., Marketing Principles, 3rd Asia-Pacific ed., Cengage, 2018, pp. 449–50

- Pride, W.M., Ferrell, O.C. Lukas, B.A., Schembri, S. Niininen, O. and Cassidy, R., Marketing Principles, 3rd Asia-Pacific ed., Cengage, 2018, p. 451

- Jones, Brian D.G.; Shaw, Eric H. (2006). "A History of Marketing Thought", Handbook of Marketing. Weitz, Barton A.; Wensley, Robin (eds), Sage, p. 41, ISBN 1-4129-2120-1.

- Thompson, D.B., An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora, ASCSA, 1993 pp. 19–21

- McGeough, K.M., The Romans: New Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, 2004, pp. 105–06

- Coleman, P., Shopping Environments, Elsevier, Oxford, 2006, p. 28

- Moore, K., and Reid., S., "The Birth of the Brand: 4000 years of Branding", Business History, Vol. 50, 2008. pp. 419–32.

- Eckhardt, G.M. and Bengtsson. A. "A Brief History of Branding in China", Journal of Macromarketing, Vol, 30, no. 3, 2010, pp. 210–21

- Eckhardt, G.M. and Bengtsson. A. "A Brief History of Branding in China", Journal of Macromarketing, Vol, 30, no. 3, 2010, p. 212

- Thrupp, S.L., The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500, pp. 7–8

- Pevsner, N. and Hubbard, E., The Buildings of England: Cheshire Penguin, 1978, p. 170

- Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516 Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The List and Index Society, no. 32, 2003

- Rebecca M. Seaman, ed. (2013). Conflict in the Early Americas: An Encyclopedia of the Spanish Empire's ... Abc-Clio. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-59884-777-2.

- Cox, N.C. and Dannehl, K., Perceptions of Retailing in Early Modern England, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate, 2007, p,. 129

- Cox, N.C. and Dannehl, K., Perceptions of Retailing in Early Modern England, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate, 2007, pp. 153–54

- Conlin, J., Tales of Two Cities: Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City, Atlantic Books, 2013, Chapter 2

- Mill, J.S., Principles of a Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy, 7th ed., London, Longman, 1909, Section IV.7.53

- Reshaping Retail: Why Technology is Transforming the Industry and How to Win in the New Consumer Dr

- Koot, G.M. (2011). "Shops and Shopping in Britain: from market stalls to chain stores" (PDF). University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Howard Moss, M., Shopping as an Entertainment Experience, Plymouth, Lexington Books, pp. 35–39

- Goldstein. J., 101 Amazing Facts about Wales, Andrews, UK, 2013

- Malcolm Gladwell, The Terrazzo Jungle Archived 9 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The New Yorker, March 15, 2004

- Byrne-Paquet, L., The Urge to Splurge: A Social History of Shopping, ECW Press, Toronto, Canada, p. 83

- Johanson, Simon (2 June 2015). "Bunnings Shifts Focus as it Upsizes Store Network". The Age. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Wahba, Phil (15 June 2017). "The Death of Retail is Greatly Exaggerated". Fortune (Print magazine). p. 34.

- Wetherell, S., "The Shopping Mall's Socialist Pre-History" Archived 20 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Jacobin Magazine, 4 August 2014

- Townsend, Matt; Surane, Jenny; Orr, Emma; Cannon, Christopher (8 November 2017). "America's 'Retail Apocalypse' Is Really Just Beginning". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Volpato, G. and Stocchetti, A., "Old and new approaches to marketing: The quest of their epistemological roots" Archived 4 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, MPRA Paper No. 30841, 2009, p. 34

- Lambda, A.J., The Art Of Retailing, McGraw-Hill, (2003), 2008, pp. 315–26

- Parker, Christopher J.; Wenyu, Lu (13 May 2019). "What influences Chinese fashion retail? Shopping motivations, demographics and spending". Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management. 23 (2): 158–175. doi:10.1108/JFMM-09-2017-0093. ISSN 1361-2026. S2CID 170031856. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Fill, C., Marketing Communications: Framework, Theories and Application, London, Prentice Hall, 1995, p. 70

- Yu-Jia, H. (2012). "The Moderating Effect of Brand Equity and the Mediating Effect of Marketing Mix Strategy On the Relationship Between Service Quality and Customer Loyalty ". International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 155–62.

- Morschett, D., Swoboda, B. and Schramm, H., "Competitive Strategies in Retailing: An Investigation of the Applicability of Porter's Framework for Food Retailers Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 13, 2006, pp. 275–87

- Constantinides, E., "The Marketing Mix Revisited: Towards the 21st Century Marketing", Journal of Marketing Management, Vo. 22, 2006, pp. 422-423

- Berens, J.S., "The Marketing Mix, the Retailing Mix and the Use of Retail Strategy Continua", Proceedings of the 1983 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS), [Part of the series Developments in Marketing Science], pp. 323–27

- Lamb, C.W., Hair, J.F. and McDaniel, C., MKTG 2010, Mason, OH, Cengage, pp. 193–94

- Verhoef, P., Kannan, P.K. and Inman, J., "From Multi-channel Retailing to Omni-channel Retailing: Introduction to the Special Issue on Multi-channel Retailing", Journal of Retailing, vol. 91, pp. 174–81. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.02.005

- Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W.C. and Ferrell, O.C., Marketing: Concepts and Strategies, Cengage, 2013, Chapter 12

- Nagle, T., Hogan, J. and Zale, J., The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing: A Guide to Growing More Profitably, Oxon, Routledge, 2016, p. 1 and 6

- Brennan, R., Canning, L. and McDowell, R., Business-to-Business Marketing, 2nd ed., London, Sage, 2011, p. 331

- Neumeier, M., The Brand Flip: Why customers now run companies and how to profit from it (Voices That Matter), 2008, p. 55

- Irvin, G. (1978). Modern Cost-Benefit Methods. Macmillan. pp. 137–160. ISBN 978-0-333-23208-8.

- Rao, V.R. and Kartono, B., "Pricing Strategies and Objectives: A Cross-cultural Survey", in Handbook of Pricing Research in Marketing, Rao, V.R. (ed), Northampton, MA, Edward Elgar, 2009, p. 15

- Hoch, Steven J.; Drèze, Xavier; Purk, Mary E. (October 1994). "EDLP, Hi-Lo, and Margin Arithmetic" (PDF). The Journal of Marketing. 58 (4): 16–27. doi:10.1177/002224299405800402. S2CID 18134783. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Kaufmann, P., "Deception in retailer high-low pricing: A 'rule of reason' approach", Journal of Retailing, Volume 70, Issue 2, 1994, pp. 115–1383.

- Guiltnan, J.P., "The Price Bundling of Services", Journal of Marketing, April 1987

- Poundstone, W., Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (and How to Take Advantage of It), New York: Hill and Wang, 2011, pp. 184–200

- Barr, A., "PayPal Deepens Retail Drive in Discover Payments Deal", Technology News. 22 August 2012

- Romis, Rafael. "Council Post: Three Ways To Crush E-Commerce: Busting Common Misconceptions". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Steven Greenhouse (27 October 2012). "A Part-Time Life, as Hours Shrink and Shift". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Hee, J.K., "Stand-alone Sale of a Free Gift: Is it effective to accentuate promotion value?" Social Behavior & Personality, Vol. 43, no. 10, 2015, pp. 1593–1606

- Cant, M.C.; van Heerden, C.H. (2008). Personal Selling. Juta Academic. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7021-6636-5.

- Monash University, Dictionary, https://business.monash.edu/marketing/marketing-dictionary/r/retail-mix Archived 13 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Impact of Retail Servicescape on Buying Behaviour", BVIMSR's Journal of Management Research, Vol 6, No. 2, 2014, pp. 10–17

- Wakefield, L.K. and Blodgett, G J., "The Effect of the Servicescape on Customers' Behavioral Intentions in Leisure Service Settings", The Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 10, No. 6, pp. 45–61.

- Hall, C.M. and Mitchell, R., Wine Marketing: A Practical Guide, pp. 182–83

- Bailey, P. (2015, April). Marketing to the senses: A multisensory strategy to align the brand touchpoints. Admap, 2–7.

- Hul, Michael K.; Dube, Laurette; Chebat, Jean-Charles (1 March 1997). "The impact of music on consumers' reactions to waiting for services". Journal of Retailing. 73 (1): 87–104. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90016-6.

- Babin, Barry J.; Darden, William R.; Griffin, Mitch (1994). "Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value". Journal of Consumer Research. 20 (4): 644. doi:10.1086/209376.

- Durvasula, S., Lysonski, S. and Andrews, J.C. (1993), "Cross-cultural generalizability of a scale for profiling consumers' decision-making styles", The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 55–65

- Sproles, G.B. (1985), "From perfectionism to faddism: measuring consumers' decision-making styles", in Schnittgrund, K.P. (Ed.), American Council on Consumer Interests (ACCI), Conference Proceedings, Columbia, MO, pp. 79–85.

- Sproles, G.B. (1983). Conceptualisation and measurement of optimal consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 421–38.

- Mishra, Anubhav A. (2015). "Consumer innovativeness and consumer decision styles: A confirmatory and segmentation analysis". The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research. 25: 35–54. doi:10.1080/09593969.2014.911199. S2CID 219645290.

- Jain, R. and Sharma, A., "A Review on Sproles & Kendall's Consumer Style Inventory (CSI) for Analyzing Decision Making Styles of Consumers", Indian Journal of Marketing, Vol. 43, no. 3, 2013

- Sproles, G.B., & Kendall, E.L., "A methodology for profiling consumers' decision-marking styles", Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol., 20 No. 2, 1986, pp. 267–79

- Bauer, H.H., Sauer, N.E., and Becker, C., "Investigating the relationship between product involvement and consumer decision-making styles", Journal of Consumer Behaviour. Vol. 5, 2006 342–54.

- Constantinides, E., "The Marketing Mix Revisited: Towards the 21st Century Marketing", Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 22, 2006, p. 421

- Ferrara, J. Susan. "The World of Retail: Hardlines vs. Softlines". Value Line. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Time, Forest. "What is Soft Merchandising?". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- "hard goods". Investor Words. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

-

Nicholson, Walter; Snyder, Christopher Mark (2014). "Perfect Competition in a Single Market". Intermediate Microeconomics and Its Application (12 ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning. p. 300. ISBN 9781133189022. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

One question raised by the growth of Internet selling is whether there will remain a separate role for retailers over the long term. If the Internet allows producers to reach customers directly, why would any role for retailing 'middlemen' remain?

- Wang, Cuimin (17 June 2021). "Analyzing the Effects of Cross-Border E-Commerce Industry Transfer Using Big Data". Mobile Information Systems. 2021: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2021/9916304. ISSN 1875-905X.

- "My publications - Global Travel Retail Market Research Report and Forecast to 2019-2023 - Page 1 - Created with Publitas.com". view.publitas.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "MoodieDavitt Report". 5 April 2023.

- "Statistics on Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) – M&A Courses | Company Valuation Courses | Mergers & Acquisitions Courses". Imaa-institute.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- "SuperValu-CVS group buys Albertson's for $17B". Phoenix Business Journal. January 2006. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- "Federated and May Announce Merger; $17 billion transaction to create value for customers, shareholders". Phx.corporate-ir.net. 28 February 2005. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- "Kmart Finalizes Transaction With Sears". Searsholdings.com. 29 September 2004. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- "M&A by Industries". Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances (IMAA). Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "China Eclipses the US to Become the World's Largest Retail Market – eMarketer". www.emarketer.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- "Top 50 Global Retailers 2021". NRF. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Top 100 Retailers 2020 List". NRF. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "Hot 100 Retailers 2020 List". NRF. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "2020 Top 100 Retailers Chart". NRF. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "US Census Bureau Monthly & Annual Retail Trade". www.census.gov. 11 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Estimated March imports at major U.S. retail container ports hit five-year low, declines expected to continue amid pandemic". PortNews. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Grocery retail in Central Europe 2012 Retail in Central Europe Archived 2 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Millward, Steven (18 August 2016). "Asia's ecommerce spending to hit record $1 trillion this year – but most of that is China". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "Fast Moving Consumer Goods". 18 November 2022. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

Further reading

- Adburgham, A., Shopping in Style: London from the Restoration to Edwardian Elegance, London, Thames and Hudson, 1979

- Alexander, A., "The Study of British Retail History: Progress and Agenda", in The Routledge Companion to Marketing History, D.G. Brian Jones and Mark Tadajewski (eds.), Oxon, Routledge, 2016, pp. 155–72

- Feinberg, R.A. and Meoli, J., [Online: "A A Brief History of the Mall Brief History of the Mall"], in Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 18, Rebecca H. Holman and Michael R. Solomon (eds.), Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 1991, pp. 426–27

- Hollander, S. C., "Who and What are Important in Retailing and Marketing History: A Basis for Discussion", in S.C. Hollander and R. Savitt (eds.) First North American Workshop on Historical Research in Marketing, Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 1983, pp. 35–40.

- Jones, F., "Retail Stores in the United States, 1800–1860", Journal of Marketing, October 1936, pp. 135–40

- Krafft, Manfred; Mantrala, Murali K., eds. (2006). Retailing in the 21st Century: Current and Future Trends. New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-28399-7.

- Kowinski, W. S., The Malling of America: An Inside Look at the Great Consumer Paradise, New York, William Morrow, 1985

- Furnee, J. H., and Lesger, C. (eds), The Landscape of Consumption: Shopping Streets and Cultures in Western Europe, 1600–1900, Springer, 2014

- MacKeith, M., The History and Conservation of Shopping Arcades, Mansell Publishing, 1986

- Nystrom, P. H., "Retailing in Retrospect and Prospect", in H.G. Wales (ed.) Changing Perspectives in Marketing, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 19951, pp. 117–38.

- Stobard, J., Sugar and Spice: Grocers and Groceries in Provincial England, 1650–1830, Oxford University Press, 2016

- Underhill, Paco, Call of the Mall: The Author of Why We Buy on the Geography of Shopping, Simon & Schuster, 2004