Rifapentine

Rifapentine, sold under the brand name Priftin, is an antibiotic used in the treatment of tuberculosis.[1] In active tuberculosis it is used together with other antituberculosis medications.[1] In latent tuberculosis it is typically used with isoniazid.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Priftin |

| Other names | 3{[(4-cyclopentyl-1-piperazinyl)imino]methyl}rifamycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a616011 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Macrolactam |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | increases when administered with food |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.057.021 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C47H64N4O12 |

| Molar mass | 877.031 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 179 to 180 °C (354 to 356 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include low neutrophil counts in the blood, elevated liver enzymes, and white blood cells in the urine.[2] Serious side effects may include liver problems or Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea.[2] It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe.[2] Rifapentine is in the rifamycin family of medication and works by blocking DNA-dependent RNA polymerase.[2]

Rifapentine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[3] In many areas of the world it is not easy to get as of 2015.[4]

Medical uses

A systematic review of regimens for prevention of active tuberculosis in HIV-negative individuals with latent TB found that a weekly, directly observed regimen of rifapentine with isoniazid for three months was as effective as a daily, self-administered regimen of isoniazid for nine months. The three-month rifapentine-isoniazid regimen had higher rates of treatment completion and lower rates of hepatotoxicity. However, the rate of treatment-limiting adverse events was higher in the rifapentine-isoniazid regimen compared to the nine-month isoniazid regimen.[5]

Pregnancy

Rifapentine has been assigned a pregnancy category C by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Rifapentine in pregnant women has not been studied, but animal reproduction studies have resulted in fetal harm and were teratogenic. If rifapentine or rifampin are used in late pregnancy, coagulation should be monitored due to a possible increased risk of maternal postpartum hemorrhage and infant bleeding.[1]

Adverse effects

Common side effects include allergic reaction, anemia, neutropenia, elevated transaminases,[1] and pyuria.[2] Overdoses have been associated with hematuria and hyperuricemia.[1]

Contraindications

Rifapentine should be avoided in patients with an allergy to the rifamycin class of drugs.[1] This drug class includes rifampicin and rifabutin.[6]

Interactions

Rifapentine induces metabolism by CYP3A4, CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 enzymes. It may be necessary to adjust the dosage of drugs metabolized by these enzymes if they are taken with rifapentine. Examples of drugs that may be affected by rifapentine include warfarin, propranolol, digoxin, protease inhibitors and birth control pills.[1]

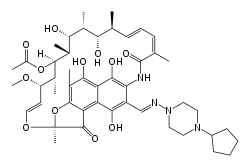

Chemical structure

The chemical structure of rifapentine is similar to that of rifamycin, with the notable substitution of a methyl group for a cyclopentane (C5H9) group.

History

Rifapentine was first synthesized in 1965, by the same company that produced rifampicin. The drug was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 1998.[7][8] It is made from rifampicin.

Rifapentine was granted orphan drug designation by the FDA in June 1995,[9] and by the European Commission in June 2010.[10]

Society and culture

Cancer-causing impurities

In August 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) became aware of nitrosamine impurities in certain samples of rifapentine.[11] The FDA and manufacturers are investigating the origin of these impurities in rifapentine, and the agency is developing testing methods for regulators and industry to detect the 1-cyclopentyl-4-nitrosopiperazine (CPNP).[11] CPNP belongs to the nitrosamine class of compounds, some of which are classified as probable or possible human carcinogens (substances that could cause cancer), based on laboratory tests such as rodent carcinogenicity studies.[11] Although there are no data available to directly evaluate the carcinogenic potential of CPNP, information available on closely related nitrosamine compounds was used to calculate lifetime exposure limits for CPNP.[11]

As of January 2021, the FDA continues to investigate the presence of 1-methyl-4-nitrosopiperazine (MNP) in rifampin or 1-cyclopentyl-4-nitrosopiperazine (CPNP) in rifapentine approved for sale in the US.[12]

See also

References

- "Priftin- rifapentine tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "Rifapentine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Nieburg P, Dubovi T, Angelo S (2015). Tuberculosis—A Complex Health Threat: A Policy Primer of Global TB Challenges. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 15. ISBN 9781442240957. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- Sharma SK, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, et al. (July 2013). "Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD007545. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007545.pub2. PMC 6532682. PMID 23828580.

- CDC. (2013) Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know. Retrieved from "CDC - Core Curriculum: What the Clinician Should Know - TB". Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2017-09-10..

- "Drug Approval Package: Priftin/Rifapentine NDA# 21024". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 March 2001. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "Priftin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "Rifapentine Orphan Drug Designation and Approval". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "EU/3/10/750". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 21 June 2010. EMA/COMP/165383/2010. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- "FDA works to mitigate shortages of rifampin and rifapentine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Laboratory analysis of rifampin/rifapentine products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links

- "Nitrosamine impurities in medications: Guidance". Health Canada. 4 April 2022.