Robin Jackson

Robert John Jackson[2][3][4] (27 September 1948 – 30 May 1998),[5] also known as The Jackal, was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary and part-time soldier. He was a senior officer in the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) during the period of violent ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles. Jackson commanded the UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade from 1975 to the early 1990s, when Billy Wright took over as leader.

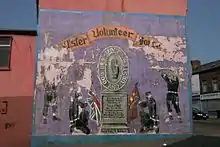

Robin Jackson | |

|---|---|

Jackson with the Ulster banner behind him | |

| Birth name | Robert John Jackson |

| Nickname(s) | Robin Jacko The Jackal |

| Born | 27 September 1948[1] Donaghmore, County Down, Northern Ireland |

| Died | 30 May 1998 (aged 49) Donaghcloney, County Down, Northern Ireland |

| Buried | St. Bartholomew Church of Ireland churchyard, Donaghmore, County Down, Northern Ireland |

| Allegiance | Ulster Volunteer Force British Army |

| Rank | Brigade commander (UVF rank) Private (UDR) |

| Unit | Mid-Ulster Brigade Ulster Defence Regiment 11th Battalion UDR |

| Conflict | The Troubles |

From his home in the small village of Donaghcloney, County Down, a few miles south-east of Lurgan, Jackson is alleged to have organised and committed a series of killings, mainly against Catholic civilians, although he was never convicted in connection with any killing and never served any lengthy prison terms. At least 50 killings in Northern Ireland have been attributed to him, according to Stephen Howe (in the New Statesman magazine) and David McKittrick (in his book Lost Lives).[6][7]

An article by Paul Foot in Private Eye suggested that Jackson led one of the teams that bombed Dublin on 17 May 1974, killing 26 people, including two infants.[8] Royal Ulster Constabulary Special Patrol Group (SPG) officer John Weir (who was also involved in loyalist killings), also maintained this in an affidavit. The information from Weir's affidavit was published in 2003 in the Barron Report, the findings of an official investigation into the Dublin bombings commissioned by Irish Supreme Court Justice Henry Barron. Journalist Kevin Dowling in the Irish Independent alleged that Jackson had headed the gang that perpetrated the Miami Showband killings, which left three members of the cabaret band dead and two wounded. Journalist Joe Tiernan and the Pat Finucane Centre also made this allegation and averted to Jackson's involvement in the Dublin bombings. When questioned about the latter, Jackson denied involvement. Findings noted in a report by the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) (released in December 2011) confirmed that Jackson was linked to the Miami Showband attack through his fingerprints, which had been found on the silencer specifically made for the Luger pistol used in the shootings.

Jackson was at one-time a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) but was discharged from the regiment for undisclosed reasons. It was stated by Weir, as well as by others including former British Army psychological warfare operative Major Colin Wallace, that Jackson was an RUC Special Branch agent.[9]

Early life and UDR career

Jackson was born into a Church of Ireland family in the small, mainly Protestant hamlet of Donaghmore, County Down,[10][11] Northern Ireland on 27 September 1948,[1] the son of John Jackson and Eileen Muriel.[10] Some time later, he went to live in the Mourneview Estate in Lurgan,[10] County Armagh before making his permanent home in the village of Donaghcloney, County Down, 5 miles (8.0 km) southeast of Lurgan. Jackson made a living by working in a shoe factory[10] and delivering chickens for the Moy Park food processing company throughout most of the 1970s.[12]

The conflict was known as "the Troubles" erupted in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s, and people from both sides of the religious/political divide were soon caught up in the maelstrom of violence that ensued. In 1972, Jackson joined the locally recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), an infantry regiment of the British Army, in Lurgan. He was attached to 11th Battalion UDR. On 23 October 1972, a large cache of guns and ammunition were stolen during an armed raid by the illegal Ulster loyalist paramilitary organisation, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), on King's Park camp, a UDR/Territorial Army depot. It is alleged by the Pat Finucane Centre, a Derry-based civil rights group, that Jackson took part in the raid while a serving member of the UDR.[13] Journalist Scott Jamison also echoed this allegation in an article in the North Belfast News,[14] as did David McKittrick in his book Lost Lives.[15]

UVF history

Around the same time Jackson was expelled from the regiment for undisclosed reasons, he joined the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade's Lurgan unit.[16] The UVF drew its greatest strength as well as the organisation's most ruthless members from its Mid-Ulster Brigade, according to journalist Brendan O'Brien.[17] The Pat Finucane Centre's allegation that he had taken part in the UVF's 23 October 1972 raid on the UDR/TA depot indicates that he was most likely already an active UVF member prior to being dismissed from the UDR.[13] Anne Cadwallader states in her 2013 book Lethal Allies that Jackson was expelled from the UDR on 4 March 1974;[18] by then he was discernibly involved in UVF activity. As the Provisional IRA continued to wage its militant campaign across Northern Ireland throughout 1972, many loyalists felt their community was under attack and their status was being threatened and sought to retaliate against Irish nationalists and republicans by joining one of the two main loyalist paramilitary organisations, the illegal UVF or the legal Ulster Defence Association (UDA). The proscription against the UVF was lifted by Merlyn Rees, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, on 4 April 1974. It remained a legal organisation until 3 October 1975, when it was once again banned by the British government.[19]

Many members of loyalist paramilitary groups such as the UVF and UDA managed to join the UDR despite the vetting process. Their purpose in doing so was to obtain weapons, training and intelligence.[20] Vetting procedures were carried out jointly by the Intelligence Corps and the RUC Special Branch and if no intelligence was found to suggest unsuitability, individuals were passed for recruitment and would remain as soldiers until the commanding officer was provided with intelligence enabling him to remove soldiers with paramilitary links or sympathies.[21]

Operating mainly around the Lurgan and Portadown areas, the Mid-Ulster Brigade had been set up in 1972 in Lurgan by Billy Hanna, who appointed himself commander. His leadership was endorsed by the UVF's supreme commander Gusty Spence.[22] Hanna was a decorated war hero, having won the Military Medal for gallantry in the Korean War when he served with the Royal Ulster Rifles. He later joined the UDR, serving as a permanent staff instructor (PSI) and holding the rank of sergeant. According to David McKittrick, he was dismissed from the regiment two years later "for UVF activity";[23] The regimental history of the UDR confirms this[24] although journalist/author Martin Dillon states in his book, The Dirty War, that at the time of his death Hanna was still a member of the UDR.[25]

Hanna's unit formed part of the "Glenanne gang", a loose alliance of loyalist extremists which allegedly functioned under the direction of the Intelligence Corps and/or RUC Special Branch.[26] It comprised rogue elements of the RUC and its Special Patrol Group (SPG), the UDR, the UDA, as well as the UVF.[26] The Pat Finucane Centre, in collaboration with an international panel of inquiry (headed by Professor Douglass Cassel, formerly of Northwestern University School of Law) has implicated this gang in 87 killings which were carried out in the 1970s against Catholics and nationalists.[13] The name, first used in 2003, is derived from a farm in Glenanne, County Armagh, which the UVF regularly used as an arms dump and bomb-making site. It was owned by James Mitchell, an RUC reservist.[27] According to John Weir, the gang usually did not use the name UVF whenever it claimed its attacks; instead, it employed the cover names of "Red Hand Commando", "Protestant Action Force", or "Red Hand Brigade". Weir named Jackson as a key player in the Glenanne gang.[28] He had close ties to loyalist extremists from Dungannon such as brothers Wesley and John James Somerville, with whom he was often spotted drinking in the Morning Star pub in the town. [29]

Alleged shooting and bombing attacks

Patrick Campbell shooting

He was first arrested on 8 November 1973 for the killing on 28 October of Patrick Campbell, a Catholic trade unionist from Banbridge who was gunned down on his doorstep. Jackson's words after he was charged with the killing were: "Nothing. I just can't believe it".[30] Campbell's wife, Margaret had opened the door to the gunman and his accomplice when they had come looking for her husband. She had got a good look at the two men, who drove off in a Ford Cortina after the shooting, and although she identified Jackson as the killer at an identity parade, murder charges against him were dropped on 4 January 1974 at Belfast Magistrates' Court.[30][3]

The charges were allegedly withdrawn because the RUC thought Mrs. Campbell knew him beforehand. Jackson confirmed this, saying that they had met previously on account that he worked in the same Banbridge shoe factory (Down Shoes Ltd.) as Patrick Campbell.[31][15] It was suggested in David McKittrick's Lost Lives that sometime before the shooting there may have been a "minor political disagreement" between Jackson and Campbell while the two men were on a night out.[15] The disagreement was allegedly over the stoppage of machinery following the deaths of three British soldiers.[32] Raymond Murray, in his book The SAS in Ireland, suggested that his accomplice in the shooting was Wesley Somerville.[4] Irish writer and journalist Hugh Jordan also maintains this allegation.[10]

When the RUC had searched Jackson's house after his arrest they discovered 49 additional bullets to those allotted a serving member of the UDR. A notebook was also found which contained personal details of over two dozen individuals including their car registration numbers.[33]

Dublin car bombings

RUC Special Patrol Group officer John Weir claimed to have first met Jackson in 1974 at Norman's Bar, in Moira, County Down.[34] [35] Weir stated in an affidavit that Jackson was one of those who had planned and carried out the Dublin car bombings.[36] According to Weir, Jackson, along with the main organiser Billy Hanna and Davy Payne (UDA, Belfast), led one of the two UVF units that bombed Dublin on 17 May 1974 in three separate explosions, resulting in the deaths of 26 people, including two infant girls. Close to 300 others were injured in the blasts; many of them maimed and scarred for life.[37][n 1][38] Journalist Peter Taylor affirmed that the Dublin car bombings were carried out by two UVF units, one from Mid-Ulster, the other from Belfast.[38]

The bombings took place on the third day of the Ulster Workers Council Strike, which was a general strike in Northern Ireland called by hardline unionists in protest against the Sunningdale Agreement and the Northern Ireland Assembly which had proposed their sharing political power with nationalists in an Executive that also planned a greater role for the Republic of Ireland in the governance of Northern Ireland. In 2003, Weir's information was published in the Barron Report, which was the findings of an official investigation into the bombings by Irish Supreme Court Justice Henry Barron.[39] Justice Barron concluded Weir's "evidence overall is credible".[40] An article by Paul Foot in Private Eye also implicated Jackson in the bombings.[8]

The producers of the 1993 Yorkshire Television documentary, The Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre, referred to Jackson indirectly as one of the bombers. However, three of his alleged accomplices, Hanna, Harris Boyle, and Robert McConnell were directly named.[41] Although the incriminating evidence against Jackson had comprised eight hours of recorded testimony which came from one of his purported chief accomplices in the bombings, the programme did not name him directly during the transmission as the station did not want to risk an accusation of libel.[9][3] The programme's narrator instead referred to him as "the Jackal". Hanna, Boyle, and McConnell were deceased at the time of the programme's airing.

According to submissions received by Mr. Justice Barron, on the morning of 17 May 1974, the day of the bombings, Jackson collected the three bombs and placed them onto his poultry lorry at James Mitchell's farm in Glenanne, which had been used for the construction and storage of the devices.[42] [43][44] He then drove across the border to Dublin, crossing the Boyne River at Oldbridge. The route had been well-rehearsed over the previous months. Hanna, then the Mid-Ulster UVF's commander and the principal organiser of the attacks, accompanied him.[45] At the Coachman's Inn pub carpark on the Swords Road near Dublin Airport, the two men met up with the other members of the UVF bombing team.[46] Jackson and Hanna subsequently transferred the bombs from his lorry into the boots of three allocated cars, which had been hijacked and stolen that morning in Belfast. The Hidden Hand producers named William "Frenchie" Marchant of the UVF's A Coy, 1st Battalion Belfast Brigade, as having been on a Garda list of suspects as the organiser of the hijackings in Belfast on the morning of the bombings. The cars, after being obtained by the gang of hijackers, known as "Freddie and the Dreamers", were driven from Belfast across the border to the carpark, retaining their original registration numbers.[47]

Journalist Joe Tiernan suggested that the bombs were activated by Hanna.[45] Sometime before 4.00 p.m., Jackson and Hanna headed back to Northern Ireland in the poultry lorry after the latter had given the final instructions to the drivers of the car bombs.[48] Upon their return, Jackson and Hanna went back to the soup kitchen they were running at a Mourneville, Lurgan bingo hall. With the UWC strike in its third day, it was extremely difficult for people throughout Northern Ireland to obtain necessities such as food. Neither man's absence had been noticed by the other helpers.[49]

Following Hanna's orders, the three car bombs (two of them escorted by a "scout" [lead] car, to be used for the bombers' escape back across the Northern Ireland border) were driven into the city centre of Dublin where they detonated in Parnell Street, Talbot Street and South Leinster Street, almost simultaneously at approximately 5.30 pm. No warnings were given. From the available forensic evidence derived from material traces at the scene, the bombs are believed to have contained, as their main tertiary explosive a gelignite containing ammonium nitrate, packed into the usual metallic beer barrel container used by loyalists in prior car bombings.[50] Twenty-three people were killed outright in the blasts, including a pregnant woman and her unborn child; three more people would later die of their injuries. The bodies of the dead were mostly unrecognisable. One girl who had been near the epicentre of the Talbot Street explosion was decapitated; only her platform boots provided a clue to her gender.[51]

The bombers immediately fled from the destruction they had wrought in central Dublin in the two scout cars and made their way north using the "smuggler's route" of minor and back roads, crossing the border near Hackballs Cross, County Louth at about 7.30 pm.[45] Thirty minutes earlier in Monaghan, an additional seven people were killed instantly or fatally injured by a fourth car bomb which had been delivered by a team from the Mid-Ulster UVF's Portadown unit.[5] According to Joe Tiernan, this attack was carried out to draw the Gardaí away from the border, enabling the Dublin bombers to cross back into Northern Ireland undetected.[45]

Jackson was questioned following the Yorkshire Television programme and he denied any involvement in the Dublin attacks.[52] His name had appeared on a Garda list of suspects for the bombings.[53] Hanna's name was on both the Garda and the RUC's list of suspects; however, neither of the two men were ever arrested or interrogated in connection with the bombings. The submissions made to the Barron Inquiry also stated that one week before the Dublin attacks, Jackson and others had been stopped at a Garda checkpoint at Hackballs Cross.[47]

Nobody was ever convicted of the car bombings. Years later, British journalist Peter Taylor in an interview with Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) politician and former senior Belfast UVF member David Ervine questioned him about UVF motives for the 1974 Dublin attacks. Ervine replied they [UVF] were "returning the serve". Ervine, although he had not participated in the bombings, explained that the UVF had wanted the Catholics across the border in the Republic of Ireland to suffer as Protestants in Northern Ireland had suffered on account of the intensive bombing campaign waged by the Provisional IRA.[54] On 28 May 1974, 11 days after the bombings, the UWC strike ended with the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the power-sharing Executive.[55]

John Francis Green killing

Statements made by John Weir affirmed Jackson's active participation in the killing of senior IRA member John Francis Green in Mullyash, near Castleblayney, County Monaghan.[56] On the evening of 10 January 1975, gunmen kicked down the front door of the "safe" house Green was staying in and, finding him alone in the living room, immediately opened fire, shooting him six times in the head at close range. The bullets all entered from the front, which indicated that Green had been facing his killers.[57] The UVF claimed responsibility for the killing in the June 1975 edition of its publication, Combat.[57] Green's killing occurred during an IRA ceasefire, which had been declared the previous month.

Assassination of Billy Hanna and leadership of UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade

Subsequent to his alleged killing of Hanna outside his home in Lurgan in the early hours of 27 July 1975, Jackson assumed command of the Mid-Ulster Brigade.[58][59][16][60][61][62][63] Hanna and his wife Ann had just returned from a function at the local British Legion Club. When he stepped out of the car, Jackson and another man approached him. After asking them "What are you playing at?" Jackson produced a pistol, walked over, and shot him twice in the head; once in the temple and afterwards in the back of the head, execution-style as he lay on the ground. His wife witnessed the killing.[10][64]

Joe Tiernan suggested that Jackson killed Hanna on account of the latter's refusal to participate in the Miami Showband killings. Hanna apparently suffered from remorse following the 1974 Dublin bombings, as he is believed by Tiernan to have instructed one of the bombers, David Alexander Mulholland to drive the car which exploded in Parnell Street, where two infant girls were among those killed.[65] According to Tiernan and the Barron Report, Mulholland was identified by three eyewitnesses. Tiernan also suggested that Hanna and Mulholland became informers for the Gardaí regarding the car bombings in exchange for immunity from prosecution. He added that although the British Army was aware of this, Jackson was never told, as it was feared he would decide to become an informer himself.[66]

Investigative journalist Paul Larkin, in his book A Very British Jihad: collusion, conspiracy, and cover-up in Northern Ireland maintained that Jackson, accompanied by Harris Boyle, had shot Hanna after learning that he had passed on information regarding the Dublin bombings.[67] Martin Dillon also claims this in The Trigger Men.[68] Dillon also stated in The Dirty War that because a number of UDR/UVF men were to be used for the planned Miami Showband attack, the UVF considered Hanna to have been a "security risk", and therefore it had been necessary to kill him.[69] David McKittrick in Lost Lives, however, suggested that Jackson had actually killed Hanna in order to obtain a cache of weapons the latter held.[70]

The UVF drew its greatest strength as well as the organisation's most ruthless members from its Mid-Ulster Brigade according to Irish journalist Brendan O'Brien.[17]

Miami Showband massacre

Jackson was also alleged by Kevin Dowling,[3] Joe Tiernan,[45] and the Pat Finucane Centre[13] to have led the UVF gang that carried out the Miami Showband ambush and massacre at Buskhill, outside Newry on 31 July 1975, which left band members Brian McCoy, Fran O'Toole and Tony Geraghty dead. Two others, Stephen Travers and Des McAlea, were wounded. Journalist Hugh Jordan also confirmed Jackson's presence at the Miami Showband ambush.[10] Harris Boyle and Wesley Somerville, both suspects in the Dublin bombings,[36] and members of both the UDR and Mid-Ulster UVF, were accidentally blown up as they placed a bomb under the driver's seat of the band's minibus which had been parked in a lay-by. The minibus, driven by trumpeter Brian McCoy (a Protestant from Caledon, County Tyrone), had been flagged-down by UVF men wearing British Army uniforms at a bogus roadside military checkpoint on the main A1 road as the band was returning home to Dublin after a performance in Banbridge. Following the premature detonation, which ripped the vehicle in half, the band members were then gunned down by the surviving UVF men.[71]

Loyalist paramilitarism researcher Jeanne Griffin suggested that Jackson had planned the ambush as a means to eliminate Brian McCoy who had strong family connections to the Orange Order and the security forces. According to Griffin's theory, Jackson had on an earlier date, approached McCoy with a proposal to secure his help in carrying out UVF attacks in the Irish Republic. When McCoy refused, Jackson saw this as a betrayal of the loyalist cause so devised the plan to ambush McCoy and his bandmates in retaliation. She also suggests that it was Jackson who shot McCoy dead in the first volley of gunfire and it was the gunman, surviving bassist Stephen Travers heard, kicking McCoy's dead body afterwards as well as firing another round into him. She based her theories on the nine bullets that had been fired from a Luger into McCoy and that Jackson's fingerprints were found on the silencer that was used for a Luger.[72]

Jackson had assumed command of the Mid-Ulster UVF just a few days before the attack, when he allegedly shot Hanna to death on 27 July.[16][63] As previously stated, Harris Boyle had reportedly accompanied Jackson to the shooting.[73] Jackson had afterwards attended Hanna's funeral, where he was photographed standing beside Wesley Somerville.[74] On 5 August 1975, Jackson was taken in and questioned by the RUC as a suspect in the Miami Showband killings; he was subsequently released two days later without facing any charges.[75] In October 1976, two serving members of the UDR (Thomas Crozier and James McDowell) received life sentences for the killings. A third man, former UDR soldier, John James Somerville was sentenced to life imprisonment in November 1981.[76]

After his arrest, Jackson accused two Criminal Investigation Department (CID) Detective Constables, Norman Carlisle and Raymond Buchanan, of having physically assaulted him on 7 August 1975 while he had been in police custody at Bessbrook RUC Station.[77] Although medical evidence presented at the trial of the accused Detective Constables raised the possibility that Jackson's injuries were self-inflicted, on 23 December 1975 a magistrate upheld the charge against the two CID men and they were fined £10 each.[75]

On 11 June 1975, more than a month prior to the Miami Showband killings, Jackson, his brother-in-law, Samuel Fulton Neill, and Thomas Crozier had been arrested for the possession of four shotguns. Neill's car was later used in the Showband ambush. Neill was fatally shot in Portadown on 25 January 1976 allegedly by Jackson for having passed on information to the RUC about the people involved in the Showband attack.[78] The Douglass Cassel panel of inquiry stated that it was unclear why Jackson, Crozier and Neill had not been in police custody at the time the Showband killings took place.[79] The panel concluded that there was "credible evidence that the principal perpetrator [of the Miami Showband attack] was a man who was not prosecuted – alleged RUC Special Branch agent Robin Jackson".[80] Former British soldier and psychological warfare operative Major Colin Wallace stated that he was told in 1974 that Jackson was working as an agent for the RUC's Special Branch. He confirmed this allegation in a letter written to a colleague dated 14 August 1975 in which he named Jackson as an RUC Special Branch agent.[81]

The Historical Enquiries Team (HET), which was set up by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) to investigate some of the more controversial Troubles-related deaths, released their report on the Miami Showband killings to the victims' families in December 2011. The findings noted in this report confirmed that Jackson was linked to the killings. It also stated that during police interrogations, Jackson had claimed that after the shootings a senior RUC officer had advised him to "lie low". Although this information was passed on to RUC headquarters and its Complaints and Discipline Department, nothing was done about it. The HET Report identified Jackson as having been an RUC Special Branch agent.[82]

Links to Captain Robert Nairac

It was stated by The Hidden Hand programme that Jackson had links to British Military Intelligence and Liaison officer Captain Robert Nairac.[9][83] The Hidden Hand alleged that Jackson and his UVF comrades were controlled by Nairac who was attached to 14th Intelligence Company (The Det). Former MI6 operative, Captain Fred Holroyd claimed that Nairac admitted to having been involved in John Francis Green's death and had shown Holroyd a colour polaroid photograph of Green's corpse to back up his claim. Holroyd believed that for some months leading up to his shooting, Green had been kept under surveillance by 4 Field Survey Troop, Royal Engineers, one of the three sub-units of 14th Intelligence. This unit was based in Castledillon, County Armagh, and according to Holroyd, was the cover name of an SAS troop commanded by Nairac and Captain Julian Antony "Tony" Ball. Nairac was himself abducted and killed by the IRA in 1977, and Ball was killed in an accident in Oman in 1981.[57][84]

Justice Barron himself questioned Holroyd's evidence as a result of two later Garda investigations, where Detective Inspector Culhane discounted Holroyd's allegations regarding Nairac and the polaroid photograph. Culhane concluded that the latter had been one of a series of official photographs taken of Green's body the morning following his killing by Detective Sergeant William Stratford, who worked in the Garda Technical Bureau's Photography Section.[57]

Weir made the following statements in relation to Jackson and Nairac's alleged mutual involvement in the Green assassination:

The men who did that shooting were Robert McConnell, Robin Jackson, and I would be almost certain, Harris Boyle who was killed in the Miami attack. What I am absolutely certain of is that Robert McConnell, Robert McConnell knew that area really, really well. Robin Jackson was with him. I was later told that Nairac was with them. I was told by ... a UVF man, he was very close to Jackson and operated with him. Jackson told [him] that Nairac was with them.[56]

In his 1989 book War Without Honour, Holyroyd claimed that Nairac had organised the Miami Showband ambush in collaboration with Jackson, and had also been present at Buskhill when the attack was carried out.[85] Bassist Stephen Travers and saxophonist Des McAlea, the two bandmembers who survived the shootings, both testified in court that a British Army officer "with a crisp, clipped English accent" had overseen the operation. However, when shown a photograph of Nairac, Travers could not positively identify him as the soldier who had been at the scene.[86] Martin Dillon in The Dirty War adamantly stated that Nairac had not been involved in the Green killing nor in the Miami Showband massacre.[87]

The Barron Report noted that although Weir maintained that Jackson and Billy Hanna had links to Nairac and British Military Intelligence, his claim did not imply that the British Army or Military Intelligence had aided the two men in the planning and perpetration of the 1974 Dublin bombings.[88] While in prison, Weir wrote a letter to a friend claiming that Nairac had ties to both Jackson and James Mitchell, owner of the Glenanne farm.[89]

The 2006 Interim Report of Mr. Justice Barron's inquiry into the Dundalk bombing of 1975 (see below) concluded that Jackson was one of the suspected bombers "reliably said to have had relationships with British Intelligence and or RUC Special Branch officers".[90][91]

In 2015, a biography of Nairac entitled "Betrayal: the Murder of Robert Nairac" was published. Written by former diplomat Alistair Kerr, the book provides documentary evidence that shows Nairac as having been elsewhere at the time of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, John Francis Green killing and Miami Showband ambush took place. On 17 May 1974 he was on a months-long training course in England; 10 January 1975 there were three witnesses who placed him on temporary duty in Derry for a secret mission; and on 31 July 1975 at 4am he had started on a road journey from London to Scotland for a fishing holiday.[92]

Other killings

1975

The 2006 Interim Report named Jackson as having possibly been one of the two gunmen in the shooting death of the McKearney couple on 23 October 1975. Peter McKearney was shot between 14 and 18 times, and his wife, Jenny 11 times. The shooting took place at their home in Moy, County Tyrone; Jackson was linked to the Sterling submachine gun used in the killings. "Glenanne gang" member Garnet Busby pleaded guilty to the killings and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[93] John Weir claimed that Jackson led the group who bombed Kay's Tavern pub in Dundalk on 19 December 1975, which killed two men.[94] Barron implicated the "Glenanne gang" in the bombing,[90] however, Jackson was not identified by any eyewitnesses at or in the vicinity of Kay's Tavern.[95] Gardaí received information from a reliable source that Jackson and his car – a Vauxhall Viva with the registration number CIA 2771 – were involved in the bombing; yet there were no witnesses who reported having seen the car.[95] The RUC stated that Jackson had been observed celebrating at a Banbridge bar at 9.00 pm on the evening of the attack in the company of other loyalist extremists. The implication was that they were celebrating the Kay's Tavern bombing.[95]

1976

The following month, on 4 January 1976, Jackson supposedly organised the "Glenanne gang"'s two coordinated sectarian attacks against the O'Dowd and Reavey families in County Armagh, leaving a total of five men dead and one injured.[94] Weir maintained that it was Jackson who shot 61-year-old Joseph O'Dowd and his two nephews, Barry and Declan, to death at a family celebration in Ballydougan, near Gilford; although Jackson had not been at the scene where the Reavey brothers had been killed twenty minutes earlier.[94] The day after the double killing, ten Protestant workmen were gunned down by the South Armagh Republican Action Force, who ambushed their minibus at Kingsmill near the village of Whitecross. The shootings were in retaliation for the O'Dowd and Reavey killings. The Glenanne gang made plans to avenge the Kingsmill victims with an attack on St Lawrence O'Toole Primary School, Belleeks. This plan, which involved the killing of at least 30 schoolchildren and their teacher, was called off at the last minute by the UVF's Brigade Staff (Belfast leadership based on the Shankill Road), who considered it "morally unacceptable" and feared it would have led to a civil war.[96]

Based on the description given by Barney O'Dowd, a survivor of the shooting attack at Ballydougan, one of the weapons used in the O'Dowd killings was a Luger with an attached silencer. [97] The findings noted in the HET Report on the Miami Showband killings revealed that on 19 May 1976, two fingerprints belonging to Jackson were discovered on the metal barrel of a home-made silencer constructed for a Luger pistol. Both the silencer and Luger, as well as more firearms, ammunition, a magazine, explosives, and bomb-making material, were found by the security forces at the farm of a man by the name of Edward Sinclair, a former member of the "B Specials". The exhibit, however, was mistakenly labelled indicating that his prints had been found on the black insulating tape wrapped around the silencer rather than the silencer itself.[98]

After several unsuccessful attempts to apprehend Jackson between 20 and 30 May, Jackson was arrested at his home on 31 May under Section 10 of the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973; he was taken to Armagh Police Station.[99] This was when the amended information regarding his fingerprints was delivered to Detective Superintendent Ernest Drew at Armagh. Drew and Detective Constable William Elder both questioned him; Jackson denied ever having been at Sinclair's farm whilst admitting knowing him through the Portadown Loyalist Club which they both frequented. When shown the Luger, silencer and magazine (but not the insulating tape), Jackson denied having handled them. When asked by Detective Superintendent Drew to provide an explanation should his fingerprints be discovered on either pistol or silencer, Jackson told him that one night at the Portadown Loyalist Club, Sinclair had asked him for some adhesive tape and Jackson claimed, "I gave him part of the roll I was using in the bar".[98]

Jackson had allegedly been using the tape whilst lapping hoses for beer kegs at the bar. In his statement to Detective Superintendent Drew, Jackson claimed that one week prior to his arrest, two high-ranking RUC officers had tipped him off about his fingerprints having been found on the insulating tape wrapped around the silencer used with the Luger. Jackson went on to say that he was forewarned, using the words: "I should clear as there was a wee job up the country that I would be done for and there was no way out of it for me".[98] On 2 June, Jackson was charged with possession of a firearm, a magazine, four rounds of ammunition and a silencer with intent to endanger life. He was detained in custody and went to trial on 11 November 1976 at a Diplock Court held at Belfast City Commission, charged only with possession of the silencer. Although the judge initially rejected his defence that his fingerprints were on the insulating tape and had "been innocently transferred to the silencer", he managed to avoid conviction when he was acquitted of the charge.[98] The trial judge, Mr. Justice Murray, had said: "At the end of the day I find that the accused somehow touched the silencer, but the Crown evidence has left me completely in the dark as to whether he did that wittingly or unwittingly, willingly or unwillingly".[97]

As a result of the judicious examination of forensic ballistics procured from original RUC reports and presented to Justice Barron, the 9 mm Luger pistol, serial no. U 4 for which the silencer was specifically made, was established as having been the same one used in the Miami Showband and John Francis Green killings.[97][76] According to journalist Tom McGurk, Miami Showband trumpeter Brian McCoy was shot nine times in the back with a Luger pistol.[100] The Miami inquiry team was never informed of these developments and Jackson was never questioned about the Miami Showband killings following the discovery of his fingerprints on the silencer. The Luger pistol serial no. U 4 was later destroyed by the RUC on 28 August 1978.[57] Barney O'Dowd claimed RUC detectives in the 1980s admitted to him that Jackson had been the man who shot the three O'Dowd men, but the evidence had not been sufficient to charge him with the killings.[101] In 2006, Barney O'Dowd spoke at the public hearings of the Houses of the Oireachtas Sub-Committee on the Barron Report Debate. He maintained that in June 1976 an RUC detective came to see him at his home and told him the gunman could not be charged with the killings as he was the "head of the UVF" and a "hard man" who could not be broken during police interrogation. Additionally the UVF had threatened to start shooting policeman like the IRA were doing if the gunman was ever charged with murder.[102]

Weir stated in his affidavit that on one occasion some months after he was transferred to Newry RUC station in October 1976, Jackson himself, and another RUC officer and "Glenanne gang" member, Gary Armstrong,[103] went on a reconnaissance in south Armagh seeking out the homes of known IRA members, with the aim of assassinating them. Jackson, according to Weir, carried a knife and hammer, and boasted to Weir that if they happened to "find a suitable person to kill", he [Jackson] "knew how to do it with those weapons".[34][n 2] They approached the houses of two IRA men; however, the plan to attack them was aborted and they drove back to Lurgan. They were stopped at an RUC roadblock near the Republic of Ireland border, but the three men were waved through, after an exchange of courtesies, despite the presence of Jackson in the car with two RUC officers.[34]

1977 and the William Strathearn killing

He was implicated by Weir in the killing of Catholic chemist, William Strathearn,[104] who was shot at his home in Ahoghill, County Antrim after two men knocked on his door at 2.00 am on 19 April 1977 claiming to need medicine for a sick child.[105] Strathearn lived above his chemist's shop. Weir was one of the RUC men later convicted of the killing, along with his SPG colleague, Billy McCaughey, and he named Jackson as having been the gunman,[94] alleging that Jackson had told him after the shooting that he had shot Strathearn twice when the latter opened the door. Weir and McCaughey had waited in Weir's car while the shooting was carried out. The gun that Jackson used had been given to him by McCaughey, with the instructions that he was only to fire through an upstairs window to frighten the occupants and make sure they "got the message", and not to kill anyone. As in the Dublin bombings, Jackson's poultry lorry was also employed on this occasion, specifically to transport himself and Robert John "R.J." Kerr, another alleged accomplice, to and from the scene of the crime. After the killing, Jackson and Kerr went on to deliver a load of chickens. Kerr was allegedly Jackson's lorry helper, assisting in loading and unloading chickens which Jackson sold for a living.[34]

Jackson was never questioned about the killing. According to an RUC detective, he was not interrogated for "reasons of operational strategy".[106] Weir suggested that "Jackson was untouchable because he was an RUC Special Branch agent."[107] The Barron Report stated that Weir had made an offer to testify against Jackson and Robert John "R.J". Kerr, but only on the condition that the murder charge against him was withdrawn. This offer was refused by the Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions who said

Kerr and Jackson have not been interviewed by the police because the police state they are virtually immune to interrogation and the common police consensus is that to arrest and interview either man is a waste of time. Both men are known to police to be very active and notorious UVF murderers. Nevertheless the police do not recommend consideration of withdrawal of charges against Weir. I agree with this view. Weir and McCaughey must be proceeded against. When proceedings against them are terminated the position may be reviewed in respect of Jackson and Kerr.[106]

It is noted in the Barron Report that Northern Ireland's Lord Chief Justice Robert Lowry was aware of Jackson and Kerr's involvement in the Strathearn killing, and that they were not prosecuted for "operational reasons".[108] Mr. Justice Barron was highly critical of the RUC's failure to properly investigate Jackson.[109] Weir declared "I think it is important to make it clear that this collusion between loyalist paramilitaries such as Robin Jackson and my RUC colleagues and me was taking place with the full knowledge of my superiors".[34]

1978–1990

Journalist Liam Clarke alleged that in early 1978, Weir and Jackson traveled to Castleblaney with the intention of kidnapping an IRA volunteer named Dessie O'Hare from a pub called The Spinning Wheel. However, when Jackson and Weir arrived, they discovered the publican had been warned of the kidnap plot and they were ordered to leave the premises.[110]

Jackson's sole conviction came after he was arrested on 16 October 1979 when a .22 pistol, a .38 revolver, a magazine, 13 rounds of ammunition, and hoods were found in his possession.[111][53] He was remanded in custody to Crumlin Road Prison in Belfast to await trial.[34] On 20 January 1981, Jackson was brought before the Belfast Crown Court on charges of possession of guns and ammunition, and was sentenced to seven years in prison.[3] He was released on 12 May 1983.[111]

A man whose description matched Jackson's was seen behaving suspiciously in the vicinity of Lurgan RUC barracks close to where three prominent republicans were later ambushed and shot by masked UVF gunmen after they left the police station on 7 March 1990. The republicans had been signing in at the station as part of their bail conditions for charges of possession of ammunition. Sam Marshall was killed in the attack; Colin Duffy and Tony McCaughey were both wounded. Although the shooting was claimed by the UVF, the gunmen were never caught. Two UVF members were later convicted of having supplied the car used in the ambush.[112]

Reputation and further allegations

Designated by Weir the "most notorious paramilitary in Northern Ireland", at least 50 killings were directly attributed to Jackson, according to journalists Stephen Howe in the New Statesman,[6] and David McKittrick in his book Lost Lives.[7] Kevin Dowling in the Irish Independent, dubbed Jackson the "Lord High Executioner of the North's notorious murder triangle", adding that he was infamous from Belfast to the Irish border for "the intensity and fury of his instinct to kill".[3] A former UDR soldier who had served with Jackson described him as a sectarian killer who had a visceral hatred of Catholics but that "you were always glad to have him with you when you were out on patrol".[113]

Unnamed intelligence officers personally acquainted with Jackson stated that he was a psychopath who would often dress up and attend the funerals of his victims because he felt a need "to make sure they were dead."[3] Described as a sardonic man who was extremely dedicated;[3][16] physically he was dark-haired, blue-eyed, "small, but firmly-built".[16] Suspicious by nature, he repeatedly advised his associates that they should never reveal secret information to anyone.[34] His paranoia and fear of recognition by his potential victims was such that he attempted to destroy all photographs of himself including school and family pictures.[114]

Psychological warfare operative Major Colin Wallace corroborated the allegations, stating that

[E]verything people had whispered about Robin Jackson for years was perfectly true. He was a hired gun. A professional assassin. He was responsible for more deaths in the North [Northern Ireland] than any other person I knew. The Jackal killed people for a living. The State not only knew that he was doing it. Its servants encouraged him to kill its political opponents and protected him.[3]

Wallace also named Jackson as having been "centrally-involved" in the Dublin bombings, but like Weir, suggested that the principal organiser had been Billy Hanna.[115] Wallace's psychological operations unit typically targeted loyalist extremists; however, during the period of 1973 and 1974 he was refused clearance to target principal members of the Mid-Ulster UVF despite an increase in paramilitary activity from the organisation. In June 1974, a month after the bombings, Wallace was denied permission to target key loyalists including Jackson and Hanna, as their names were on a list that excluded them from being targeted for psychological operations. This appeared to indicate that in practice, those members of paramilitaries whose names were listed were also excluded from being targeted for prosecution.[116]

Liam Clarke of the Sunday Times made the following statements regarding Jackson and his reported special relationship with the security forces and military intelligence:

Jackson had many allies still serving in the UDR and close links to special forces soldiers. These included Bunny Dearsley of military intelligence and Robert Nairac, Tony Ball, and other soldiers attached to the undercover 14th Intelligence Unit. These officers met him at a bar in Moira and many suspect that he was involved in murders set up by military contacts at that time. In the late 1970s, he [Jackson] was a binge drinker and sometimes boasted to UVF associates of "someone looking after me". Some took this as a reference to God or even the Devil, but the most likely explanation is that it referred to members of the Army's intelligence corps.[117]

Originally nicknamed "Jacko",[15] Jackson was given the more sinister sobriquet, "the Jackal" by Sunday World newspaper's Northern Ireland editor Jim Campbell when he investigated and exposed Jackson's alleged paramilitary activities – including his involvement in the Miami Showband killings – and links to British Military Intelligence.[4] In retaliation, Jackson reportedly approached members of the violent loyalist Shankill Butchers gang in Belfast, who (at Jackson's request) shot and seriously wounded Campbell on 18 May 1984.[118][119] According to journalist Joe Gorrod of The Mirror, it was reported in the Irish Times that the SAS took Jackson abroad where he received specialist training. In the late 1980s, he was also sent by MI5 to South Africa and Australia to buy weapons that were shipped back to loyalist paramilitaries and Ulster Resistance[n 3] in Northern Ireland.[120] Gorrod wrote that Jackson kept hidden files that incriminated the politicians and businessmen who were involved with Jackson in the loyalist arms shipments.[121]

In his book Loyalists, British journalist Peter Taylor devotes pages 187–195 to the loyalists' South African arms deals which had taken place in the late 1980s. Jackson's name does not appear in the account nor is Australia referred to. Joe Gorrod is the only journalist to make these allegations although Henry McDonald (of The Guardian) affirmed that Jackson lived for a period of time in South Africa during the 1980s.[122] The purported files, which were kept with a friend, would have ensured Jackson that he would never be sentenced to lengthy imprisonment.[121]

Weapons used in the 1994 UVF shooting attack on patrons in the Heights Bar at Loughinisland were later found to have come from the South African arms shipment that had ended up in the hands of Robin Jackson.[123]

Succeeded by Billy Wright

In the early 1990s, he handed over command of the Mid-Ulster UVF to Portadown unit leader Billy Wright, also known as "King Rat".[16] Wright formed the breakaway Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) in 1996. This was after he and his Portadown unit had been stood down by the UVF's Brigade Staff in Belfast on 2 August 1996, following the unauthorised killing of a Catholic taxi driver by members of Wright's group outside Lurgan during the Drumcree disturbances when the UVF were on ceasefire. Although Wright took the officially disbanded Portadown unit with him to form the LVF, Jackson, despite being on friendly terms with Wright, remained loyal to the UVF leadership as did most of the other Mid-Ulster Brigade units. Wright was shot dead inside the Maze Prison on 27 December 1997 by Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) inmates while waiting in a prison van that was transporting him to a visit with his girlfriend. Wright had been sentenced to eight years imprisonment for having threatened a woman's life.

Jackson was confronted in 1998 by the son of RUC Sergeant Joseph Campbell, a Catholic Sergeant gunned down outside the Cushendall, County Antrim RUC station in February 1977, as he was locking up. It was rumoured that Jackson had been the hitman sent to shoot Campbell on behalf of an RUC Special Branch officer. Weir, in his affidavit, claimed Jackson, prior to Campbell's shooting, had informed him of the RUC officer's request.[34][124] Jackson, by then dying of cancer, told Campbell's son that he had not been involved in the killing. The UVF, at a secret meeting with journalists, declared that Jackson had no part in Campbell's killing.[16] The case was later placed under investigation by the Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland.[125]

Death

Jackson died of lung cancer at his Donaghcloney home on 30 May 1998;[3][126] he was buried on 1 June in a private ceremony in the St Bartholomew Church of Ireland churchyard in his native Donaghmore, County Down. His grave, close to that of his parents, is unmarked apart from a steel poppy cross.[10] He was 49 years old.[1] His father had died in 1985; his mother outlived Jackson for five years.[10]

After Jackson's death, one of his friends told Gorrod that Jackson had no regrets about his UVF activities, but that due to his religious upbringing he was tormented by feelings of remorse on his deathbed, believing that he had been "drawn into a world of evil that wasn't of his making". One of his last wishes was that the secret documents incriminating the politicians and businessmen with whom he associated be released to the public.[121] Liam Clarke suggested the killing of Billy Hanna was the only killing Jackson ever regretted, admitting it had been "unfair" to kill him.[70]

Journalist Martin O'Hagan had been in the process of writing a book about Jackson but O'Hagan's assassination by the LVF in 2001 prevented its completion. Along with Billy Hanna and other senior loyalists, Jackson was commemorated in the UVF song Battalion of the Dead. In May 2010, angry relatives of UVF victims unsuccessfully sought the removal of the song from YouTube.[127]

See also

Notes

- The three explosions which occurred in the city centre of Dublin on 17 May 1974 resulted in the deaths of 26 people; another seven people died in the Monaghan bomb, bringing the total of deaths to 33.

- This incident had to have taken place after 11 November 1976, as Jackson was in custody from 31 May to the time of his trial, which was held on 11 November.

- Ulster Resistance was a paramilitary movement founded on 10 November 1986 by unionists opposed to the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement.

References

- Notes

- Tiernan 2010, p. 152

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 85.

- "Day of 'the Jackal' has finally drawn to a close". Irish Independent, Kevin Dowling, 4 June 1998

- Murray 1990, p. 133

- "Cain Events: Dublin and Monaghan Bombs". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- "Killing Fields". New Statesman. Stephen Howe. 14 February 2000. Retrieved 2 February 2011

- McKittrick 1999, p. 724

- "The Barron Report identified at least nine men who may have been involved in the bombing of Dublin and Monaghan in 1974. Three are known to be dead". Irish Times – Newshound: daily Northern Ireland news catalog. 12 December 2003 Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 April 2011. Paul Foot's 1993 article went on to add that Jackson "has continued murdering people ever since, to the profound indifference of the authorities".

- The Hidden Hand- The Forgotten Massacre, Yorkshire Television, 1993

- Jordan, Hugh (6 January 2019). "The Jackal's Unmarked Grave". Sunday World (Dublin, Ireland).

- McKittrick 1999, p. 718

- Tiernan 2010, p. 90

- Collusion in the South Armagh/Mid Ulster Area in the mid-1970s Archived 26 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Scott Jamison. "UDR guns used in murder of Catholic workmen". North Belfast News, 27 September 2010. retrieved 30 April 2011

- McKittrick 1999, p. 398

- "UVF Rules Out Jackal Link To Murder". The People (London, England). 30 June 2002. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021.

- O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sein Fein, Second Edition. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press. p. 92. Google Books; retrieved 6 March 2011

- Gerry Moriarty. "Loyalism's most prolific sectarian killer may have enjoyed indefensible relationship with RUC officers", The Irish Times, 25 October 2013; retrieved 29 October 2013.

- Taylor 1999, p. 124

- "CAIN: Public Records: Subversion in the UDR". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- CAIN Archive:Public Records: Subversion in the UDR

- Joe Tiernan. "Sunningdale pushed hardliners into fatal outrages in 1974", Irish Independent, 16 May 1999; retrieved 6 May 2011.

- McKittrick 1999, p. 554

- Potter, John Furniss (2001). A Testimony to Courage: The Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969–1992. Pen & Sword Books, Ltd. p. 90

- Dillon 1991, p. 218

- The Cassel Report (2006), pp. 8, 14, 21, 25, 51, 56, 58–65.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 144–45.

- John Weir: "I'm lucky to be above the ground". Article in Politico.ie, by Frank Connolly, 16 November 2006; retrieved 14 February 2011

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, p. 99.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 259.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 259–260.

- "Widow to sue police chief and MoD". Belfast Telegraph. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2021

- Cadwallader, Anne (2013). Lethal Allies: the charmed life of a sectarian killer retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Seeing Red", John Weir Affadavit [sic], John Weir statement Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 3 January 1999; retrieved 13 December 2010.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 141, 161.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 145–146.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 146.

- Taylor 1999, p. 125

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 141–162.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 60

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights, Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (The Barron Report), December 2003, Appendices: The Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre. p. 15 Retrieved 7 October 2011

- "Sunningdale pushed hardliners into fatal outrages in 1974". Irish Independent. Joe Tiernan. 16 May 1999 "The bombs, which were earlier stored at the home of a Protestant farmer near Markethill in Co. Armagh were transported across the border to Whitehall by Robin Jackson in a chicken lorry. Jackson drove a chicken lorry around Ireland for a living for a number of years in the 1970s".

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 287. Mr Justice Barron concluded in his report regarding the Dublin and Monaghan car bombings: "It is likely that the farm of James Mitchell at Glenanne played a significant part in the preparation for the attacks [Dublin and Monaghan bombings]. It is also likely that members of the UDR and RUC either participated in, or were aware of those preparations"..

- Tiernan 2010, p. 94

- "Net is closing in on Dublin car bombers". Sunday Independent. Joe Tiernan. 2 November 2003. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Tiernan 2010, pp. 96–97

- O'Maolfabhail, Donal (19 January 2003). "How loyalists got the bombs to Dublin". Sunday Business Post. Dublin. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Tiernan 2010, p. 100

- Tiernan 2010, pp. 101–102

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights, Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (The Barron Report), December 2003, Appendices: The Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre, p.64-71 Retrieved 7 October 2011

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights, Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (The Barron Report), December 2003, Appendices: The Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre, p.5; retrieved 7 October 2011

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 85, 119.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 114

- Taylor 1999, p. 126

- Taylor 1999, p. 137

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 206.

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (The Barron Report), December 2003, Appendices (pp. 4-20): The murder of John Francis Green, cain.ulst.ac.uk; accessed 17 July 2014.

- CAIN Events: Dublin and Monaghan Bombs; retrieved 8 December 2010.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 134, 146–47, 172, 176, 255, 257–58.

- Taylor, Peter (2001). Brits: the war against the IRA. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 188

- "Notorious UVF unit 'to be stood down'". Belfast Telegraph. 12 March 2006; retrieved 25 January 2012

- "The Dundalk Bombing, 1975", 13 July 2006.

- Tiernan 2000, pp. 110–111

- Dillon 1991, p. 199

- Tiernan 2000, pp. 108–109

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 61.

- Larkin, p.182

- Dillon, Martin (2003). "The Trigger Men". Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. p.25

- Dillon 1991, p. 219

- McKittrick 1999, p. 555

- Taylor 1999, pp. 147–148

- Wharton, Ken (2013). Wasted Years, Wasted Lives, Vol. 1: The British Army in Northern Ireland. Solihull: Helion & Company Ltd. p. 108.

- Dillon, Martin (2003). The Trigger Men. UK: Mainstream. p.25

- McPhilemy 1998, p. 316

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, pp. 158–159.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 110

- Murray 1990, p. 140

- McKittrick 1999, p. 619

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 112

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 68

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 172.

- "Miami Showband massacre: HET raises collusion concerns". BBC News. 14 December 2011

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 136.

- "Nairac: An undercover hero or a maverick fool?", Belfast Telegraph. 13 May 2007; retrieved 13 December 2010.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, p. 160 sourced from Fred Holroyd, Nick Burbridge (1989). War Without Honour. Hull: Medium. pp.78–79.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, p. 160.

- Dillon 1991, pp. 174, 221

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 239.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, pp. 142–43.

- "Barron Links Glenanne Gang to 1975 Dundalk Bombing". The Green Ribbon. Tom Griffin. 15 July 2006 Retrieved 3 February 2011

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, p. 135.

- "Evidence clears Robert Nairac of murders he has been linked to: author". News Letter (Belfast, UK). 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, pp. 171, 182, 190.

- Politics.ie:John Weir (EX RUC) - Institutionalized collusion and how we carried it out. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights 2006, p. 104.

- "UVF Planned to Kill 30 Children". The Irish News by Barry McCaffrey and Seamus McKinney. 9 July 2007 Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 February 2011

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 260.

- "Miami Showband massacre: Involvement of UVF Man Robin Jackson". Pat Finucane Centre. 14 December 2011; retrieved 15 December 2011. Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Issues relating to Robert 'Robin' Jackson". Pat Finucane Centre. p.73 Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 17 December 2011

- "The mystery of the Miami murders" by Tom McGurk Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Sunday Business Post, the Post.ie. 31 July 2005; retrieved 15 December 2010.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 52

- Sub-Committee on the Barron Report – 26 September 2006 Public Hearings on the Barron Report, Houses of the Oireachtas, Tuesday, 26 September 2006, p. 3; retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 115

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 142.

- McKittrick 1999, p. 716

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 258.

- Smith Dornan Dehn, Prentice v. McPhilemy, The Troubles I've Seen, 1 September 1999

- Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence, and Women's Rights Sub-Committee on the Barron Report 18 February 2004, p. 2; retrieved 8 January 2011.

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 70

- "RUC men's secret war against the IRA" by Liam Clarke, Sunday Times, 7 March 1999.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 261.

- "Push for inquest over UVF murder of Sam Marshall after HET report", Belfast Telegraph. 6 March 2012; retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Loyalism's most prolific sectarian killer may have enjoyed indefensible relationship with RUC officers". The Irish Times. Gerry Moriarty. 25 October 2013 retrieved 19 May 2016

- "The Jackal; Face of Evil Assassin Who Slaughtered 40 Innocents (News)". The People (London, England) via HighBeam Research (subscription required). 7 June 1998. Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (The Barron Report) 2003, p. 174. The Barron Report stated on page 169 that "Colin Wallace is an important source of information about the workings of the intelligence community in Northern Ireland during the period preceding and following the bombings in Dubin and Monaghan on 17 May 1974. His work for the Information Policy unit gave him access to information denied to all but a few"..

- Cassel et al. 2006, p. 72

- "The policeman and 'the Jackal'". The Sunday Times by Liam Clarke. 7 March 1999.

- "Fearless Sunday World reporter writes his last column". Press Gazette. John Keane. 16 November 2007; retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "On the first anniversary of Martin O'Hagan's murder". National Union of Journalists. 3 January 2003; retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Hayes 2005, p. 618

- Gorrod, Joe (8 June 1998). "Loyalist killers fear dead Jackal's secrets; Hidden files detail gun gangs' weapons deals". The Mirror (London, UK).

- "Miami Showband killings: police tipoff helped suspect elude justice, says report", by Henry McDonald, The Guardian. 15 December 2011; retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Jackson linked to massacre". Banberidge Leader. 10 June 2016 Retrieved 5 November 2016

- "Search For the Truth in a Trail of Murder" Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 14 February 2011.

- "Widow's Appeal Over RUC Killing", BBC News; retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Hayes 2005, p. 617

- "Victims seek YouTube ban for UVF song". Sunday Life. Belfast. 23 May 2010.

- Bibliography

- Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (December 2003). "Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings (The Barron Report 2003)" (PDF). Dublin: Oireachtas. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Houses of the Oireachtas, Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights (July 2006). "Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay's Tavern, Dundalk" (PDF). Dublin: Oireachtas. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cassel, Douglass; Kemp, Susie; Pigou, Piers; Sawyer, Stephen (October 2006), Report of the Independent International Panel on Alleged Collusion in Sectarian Killings in Northern Ireland (The Cassel Report, 2006) (PDF), Center for Civil and Human Rights, Notre Dame Law School, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011, retrieved 29 March 2012

- Dillon, Martin (1991). The Dirty War. London: Arrow Books.

- Hayes, Declan (2005). The Japanese Disease: sex and sleaze in modern Japan. Lincoln, NE: Universe.

- The Hidden Hand: The Forgotten Massacre, Yorkshire Television, 1993

- McKittrick, David (1999). Lost Lives. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 9781840182279.

- McPhilemy, Sean (1998). The Committee: Political Assassination in Northern Ireland. Boulder, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers.

- Murray, Raymond (1990). The SAS in Ireland. Ireland: Mercier Press.

- Taylor, Peter (1999). Loyalists. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 0-7475-4519-7.

- Tiernan, Joe (2000). The Dublin Bombings and the Murder Triangle. Ireland: Mercier Press. ISBN 1-85635-320-6.

- Tiernan, Joe (2010). The Dublin and Monaghan Bombings. Eaton Publications.