Police Service of Northern Ireland

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI; Irish: Seirbhís Póilíneachta Thuaisceart Éireann;[6] Ulster-Scots: Polis Service o Norlin Airlan) is the police force that serves Northern Ireland. It is the successor to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) after it was reformed and renamed in 2001 on the recommendation of the Patten Report.[7][8][9][10]

| Police Service of Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

The Service Emblem | |

| Abbreviation | PSNI |

| Motto | Keeping People Safe |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 4 November 2001 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Annual budget | £836.7M (FY 2014/15)[1] |

| Legal personality | Police service |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

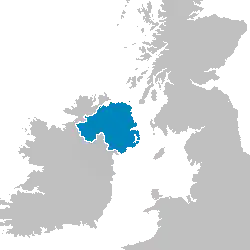

| National agency | Northern Ireland |

| Operations jurisdiction | Northern Ireland |

| |

| Police Service of Northern Ireland area | |

| Size | 14,130 km2 (5,460 sq mi)[2] |

| Population | 1,903,100 |

| Governing body | Northern Ireland Executive |

| Constituting instrument | |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Overviewed by | Northern Ireland Policing Board |

| Headquarters | Belfast[3] |

| Police officers | 6,700 |

| Police staffs | 2,219 |

| Agency executives |

|

| Departments | 12

|

| Regions | 8 |

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 79[4] |

| Watercrafts | Yes |

| Aircraft | 3 helicopters 1 fixed-wing |

| Dogs | 28[5] |

| Website | |

| www | |

Although the majority of PSNI officers are Ulster Protestants, this dominance is not as pronounced as it was in the RUC because of positive action policies. The RUC was a militarised police force[11][12][13] and played a key role in policing the violent conflict known as the Troubles. As part of the Good Friday Agreement, there was an agreement to introduce a new police service initially based on the body of constables of the RUC.[14][15] As part of the reform, an Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland (the Patten Commission) was set up, and the RUC was replaced by the PSNI on 4 November 2001.[16][17] The Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000 named the new police service as the Police Service of Northern Ireland (incorporating the Royal Ulster Constabulary); shortened to Police Service of Northern Ireland for operational purposes.[15][18]

All major political parties in Northern Ireland now support the PSNI. At first, Sinn Féin, which represented about a quarter of Northern Ireland voters at the time, refused to endorse the PSNI until the Patten Commission's recommendations were implemented in full. However, as part of the St Andrews Agreement, Sinn Féin announced its full acceptance of the PSNI in January 2007.[19]

In comparison with the other 44 territorial police forces of the United Kingdom, the PSNI is the third largest in terms of officer numbers (after the Metropolitan Police Service and Police Scotland) and the second largest in terms of geographic area of responsibility, after Police Scotland. The PSNI is about half the size of Garda Síochána in terms of officer numbers.

Organisation

The senior officer in charge of the PSNI is its chief constable. The chief constable is appointed by the Northern Ireland Policing Board, subject to the approval of the Minister of Justice for Northern Ireland. The Chief Constable of Northern Ireland is the third-highest paid police officer in the UK (after the Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police).[20] The current chief constable is Jon Boutcher, who was appointed on an interim basis after the resignation of Simon Bryne in September 2023.[21]

The police area is divided into eight districts, each headed by a chief superintendent. Districts are divided into areas, commanded by a chief inspector; these in turn are divided into sectors, commanded by inspectors. In recent years, under new structural reforms, some chief inspectors command more than one area as the PSNI strives to make savings.

In 2001 the old police divisions and sub-divisions were replaced with 29 district command units (DCUs), broadly coterminous with local council areas. In 2007 the DCUs were replaced by eight districts ('A' to 'H') in anticipation of local government restructuring under the Review of Public Administration. Responsibility for policing and justice was devolved to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 9 March 2010, although direction and control of the PSNI remains under the chief constable.

In addition to the PSNI, there are other agencies which have responsibility for specific parts of Northern Ireland's transport infrastructure:

Jurisdiction

PSNI officers have full powers of a constable throughout Northern Ireland and the adjacent United Kingdom waters. Other than in mutual aid circumstances they have more limited powers of a constable in the other two legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom—England and Wales, and Scotland. Police staff, although non-warranted members of the service, contribute to both back-office, operational support and front-line services, sometimes operating alongside warranted colleagues.

Co-operation with Garda Síochána

The Patten Report recommended that a programme of long-term personnel exchanges should be established between the PSNI and the Garda Síochána, the national police force of the Republic of Ireland. This recommendation was enacted in 2002 by an Inter-Governmental Agreement on Policing Cooperation, which set the basis for the exchange of officers between the two services.[22] There are three levels of exchanges:

- Personnel exchanges, for all ranks, without policing powers and for a term up to one year

- Secondments: for ranks from sergeant to chief superintendent, with policing powers, for up to three years

- Lateral entry by the permanent transfer of officers for ranks above inspector and under assistant commissioner

The protocols for these movements of personnel were signed by both the Chief Constable of the PSNI and the Garda Commissioner on 21 February 2005.[23]

Accountability

The PSNI is supervised by the Northern Ireland Policing Board.

The Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland deals with any complaints regarding the PSNI, and investigates any allegations of misconduct by police officers. Police staff do not fall under the ombudsman's jurisdiction. The current Police Ombudsman is former Oversight Commissioner Michael Maguire, who took over from Al Hutchinson in July 2012. The Oversight Commissioner was appointed to ensure that the Patten recommendations were implemented 'comprehensively and faithfully', and attempted to assure the community that all aspects of the report were being implemented and being seen to be implemented. The oversight role ended on 31 May 2007, with the final report indicating that of Patten's 175 recommendations, 140 had been completed with a further 16 "substantially completed".[24]

The PSNI is also internally regulated by its Professional Standards Department, who can direct local "professional standards champions" (superintendents at district level) to investigate relatively minor matters, while a "misconduct panel" will consider more serious misconduct issues. Outcomes from misconduct hearings include dismissal, a requirement to resign, reduction in rank, monetary fines and cautions.

Recruitment

.JPG.webp)

The PSNI was initially legally obliged to operate an affirmative action policy of recruiting 50% of its trainee officers from a Catholic background and 50% from a non-Catholic background, as recommended by the Patten Report, in order to address the under-representation of Catholics that had existed for many decades in policing; in 2001 the RUC was almost 92% Protestant. Many unionist politicians said the "50:50" policy was unfair, and when the Bill to set up the PSNI was going through Parliament, Minister of State Adam Ingram stated: "Dominic Grieve referred to positive discrimination and we hold our hands up. Clause 43 refers to discrimination and appointments and there is no point in saying that that is anything other than positive discrimination."[25] However, the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission cited international human rights law to show that special measures to secure minority participation were in accordance with human rights standards and did not in law constitute 'discrimination'.[26]

By February 2011, 29.7% of the 7,200 officers were from a Catholic background, but among the 2,500 police staff (non-warranted members), where the 50:50 rule operated only for larger recruitment drives, the proportion of Catholics was just 18%.[27] The British Government nevertheless proposed to end the 50:50 measure, and provisions for 'lateral entry' of Catholic officers from other police forces, with effect from the end of March 2011.[28] Following a public consultation the special measures were ended in respect of police officers and police staff in April 2011.

Deloitte conducted recruitment exercises on behalf of the PSNI, and was the dominant firm in the Consensia Partnership which existed from 2001 to 2009.

As of 2017, the PSNI have announced that it will be introducing new schemes to increase the number of Catholics in the force. The PSNI is focusing on tackling the fear factor of joining the service as violent dissident Republicans are discouraging Catholics from joining and continue to attack Catholic officers.[29]

Policies

In September 2006 it was confirmed that Assistant Chief Constable Judith Gillespie approved the PSNI policy of using children as informants including in exceptional circumstances to inform on their own family but not their parents. The document added safeguards including having a parent or "appropriate adult" present at meetings between juveniles and their handler. It also stressed a child's welfare should be paramount when considering the controversial tactics and required that any risk had been properly explained to them and a risk assessment completed.[30]

Structure

As of April 2023, the PSNI is structured with the following departments.

- Crime Department[31]

- Organised Crime Branch

- Serious Crime Branch

- Intelligence Branch

- Specialist Operations Branch

- Crime Support Branch

- Public Protection Branch

- Justice Department[32]

- Legacy and Disclosure Branch

- Criminal Justice Branch

- Contact Management

- Custody

- Local Policing[33]

- Operational Support[34]

- Armed Response Unit

- Close Protection Unit

- Dog Section

- Emergency Planning Unit

- Firearms and Explosives Branch

- Information Security Unit

- Operational Planning Hub

- Operational Policy Unit

- Police Search Advisor

- Operational and Tactical Development Unit

- Tactical Support Group

- Road Policing Unit

- Scientific Support

- People and Organisational Development[35]

- Strategic Planning and Transformation[36]

- Professional Standards Department[37]

- Discipline Branch

- Anti-Corruption Unit

- Service Vetting Unit

- Corporate Services[38]

Specialist units

Armed Response Unit

Specially-trained Armed Response Unit (ARU) officers support other parts of PSNI when faced with people who are carrying weapons such as knives and firearms.

Headquarters Mobile Support Unit

Headquarters Mobile Support Unit (HMSU) officers are trained to Specialist Firearms Officer (SFO) and Counter Terrorist Specialist Firearms Officer (CTSFO) standards. HMSU officers undergo a 26-week training program including firearms, unarmed combat, roping, driving and photography.

HMSU is the tactical unit of the PSNI.

Tactical Support Group

Tactical Support Group (TSG) officers provide a range of core and specialist services to district policing teams.[39]

Core TSG functions include public order, counter terrorism and crime reduction, community safety, crime scene response, and surveillance capability.

Specialist TSG skills include:

- specialist search teams

- police search advisors (pölsa)

- method of entry – gain entry to premises

- specialist counter terrorist / anti-crime patrols

- marine response

- enhanced medical aid

- high risk escorts

- chemical biological radiological nuclearesponse

- close protection

- roads policing

- mutual aid to other uk police services

- public order

Uniform

The colour of the PSNI uniform is bottle green. Pre-1970s RUC uniforms retained a dark green called rifle green, which was often mistaken as black. A lighter shade of green was introduced following the Hunt Report in the early 1970s, although Hunt recommended that British blue should be introduced. The Patten report, however, recommended the retention of the green uniform (Recommendation No. 154).[40] The RUC officially described this as 'rifle green'. When the six new versions of the PSNI uniform were introduced, in March 2002, the term 'bottle green' was used for basically the same colour to convey a less militaristic theme. In 2018 a formal review was launched about the current uniform after officers gave feedback on it.

On 31 January 2022, a new uniform was introduced for frontline officers.[41] This change replaced the white shirt and tie that was worn since 2001 with a green wicking material t-shirt. This new style shirt is embroidered with the PSNI crest on the left breast and the word Police on the left collar and both sleeves. The new shirt also facilitates the wearing of epaulettes to display rank and numerals. This modern workwear is similar to Police Scotland aside from colour and some police services in England and Wales. Officer headwear has remained the same and traditionally consists of peaked forage caps for males and kepi style hats for females. Baseball style caps are worn by tactical units.

Badge and flag

The PSNI badge features the St. Patrick's saltire, and six symbols representing different and shared traditions:

- The Scales of Justice (representing equality and justice)

- A crown (a traditional symbol of royalty but not the St Edward's Crown worn by or representing the British Sovereign)

- The harp (a traditional Irish symbol but not the Brian Boru harp used as an official emblem in the Republic)

- A torch (representing enlightenment and a new beginning)

- An olive branch (a peace symbol from Ancient Greece)

- A shamrock (a traditional Irish symbol, used by St Patrick, patron saint of all Ireland, to explain the Christian Trinity)

The flag of the PSNI is the badge in the centre of a dark green field. Under the Police Emblems and Flags Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2002 no other flag can be used by the PSNI and it is the only one permitted to be flown on any PSNI building, vehicle, aircraft or vessel.[42]

Equipment

Body armour

PSNI officers routinely wear bulletproof vests and in recent years have been issued the stab vests worn by most UK police officers and the Gardaí. Beginning in December 2007 bulletproof vests were required for PSNI officers patrolling in the Greater Belfast and Greater Derry City areas owing to the threat from dissident republicans.[43] In 2009 the PSNI issued an upgraded and redesigned bulletproof vest to operational officers. While the bulletproof vest offers a high level of ballistic protection many officers prefer the lighter and more comfortable stab vest. Both are issued to each operational officer and the wearing of body armour generally comes down to personal preference, except in areas of high threat.

Firearms

The elevated threat level posed by armed paramilitary groups means that, unlike the majority of police services in the United Kingdom and the Garda Síochána in the neighbouring Republic of Ireland, all PSNI officers receive firearms training and are routinely armed while on duty, with officers also being allowed to carry firearms while off-duty.[44][45][46] Historically, RUC officers were issued with the Ruger Speed-Six revolver and had access to the Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine gun and the Heckler & Koch G3 and Heckler & Koch HK33[47] rifles (which replaced the earlier Sterling submachine guns and Ruger AC-556 select-fire rifles between 1992 and 1995), with the PSNI inheriting these weapons upon formation; subsequently, the Glock 17 pistol began superseding the Speed-Six revolvers from 2002 onwards, with only fifteen revolvers remaining in service a decade later,[48][49] while Heckler & Koch G36 variants were procured to supplement the MP5, G3, and HK33.[50][51] L104 riot guns are available for crowd control purposes.[52] Long arms are still routinely carried in areas of higher threat such as Derry Cityside, North and West Belfast or various border areas.

Vehicles

.jpg.webp)

The best known PSNI vehicle is the Land Rover Tangi but with the improving security situation these are less likely to be used for everyday patrols and are more likely to be used for crowd control instead. In 2011 it was announced that some of the Tangis were to be replaced, due to the ongoing security threat and the age of the current fleet. This led to the creation of the PANGOLIN – Armoured Public Order Vehicle – designed and built by OVIK Special Vehicles (part of the OVIK Group), 60 Mk1 and 90 Mk2 variants have been delivered and are currently in service.[53] Also a number of Public Order Land Rovers made by Penman are currently in service.[54]

In addition to other cars, vans and motorcycles, the PSNI also have a fleet of 242 bicycles which are used for city centres and walkway patrols.[55]

Air support

In 2014 the Air Support Unit responded to over 4,000 callouts, 12 were Casualty evacuations and participated in over 250 missing people searches.[56] All aircraft are used for investigations, anti-crime operations, traffic management, search and rescue, public order situations, crime reduction initiatives and tackling terrorism.

Helicopters

.jpg.webp)

In May 2005, the PSNI took delivery of its first helicopter, a Eurocopter EC 135, registration G-PSNI and callsign Police 44. In 2010, the PSNI took delivery of its second aircraft, a Eurocopter EC 145 registration G-PSNO and callsign Police 45 at a cost of £7 million. In July 2013, a third helicopter entered service, Eurocopter EC 145, registration G-PSNR and callsign Police 46.[57][58]

Fixed wing aircraft

The PSNI operates two fixed wing aircraft for aerial surveillance.[59] In August 1992, a Britten-Norman BN-2T Islander entered service with registration G-BSWR and callsign Scout 1.[60] In July 2011, the aircraft sustained damage during a crash-landing at Aldergrove.[61] In June 2013, prior to the G8 summit, a Britten-Norman Defender 4000 entered service with registration G-CGTC and callsign Scout 2.[62]

Other items

Other items of equipment include Hiatt Speedcuffs, CS (irritant) Spray, Monadnock autolock batons with power safety tip and Hindi cap, a first aid pouch, a TETRA radio (Motorola MTH800) and a torch with traffic wand and limb Restraints. The PSNI plan to distribute 2100 BlackBerry devices to officers by the end of March 2011 and by March 2012 they plan to distribute an additional 2000 devices.[63]

List of chief constables

| From | To | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2002 | Sir Ronnie Flanagan | |

| 2002 | 2002 | Colin Cramphorn | Acting |

| 2002 | 2009 | Sir Hugh Orde | |

| 2009 | 2009 | Judith Gillespie | Acting |

| 2009 | 2014 | Sir Matt Baggott | |

| 2014 | 2019 | Sir George Hamilton | |

| 2019 | 2023 | Simon Byrne | |

| 2023 | 2023 | Mark Hamilton | Acting |

| 2023 | Present | Jon Boutcher | Interim |

Ranks

In the PSNI there are also Special constables known as a Reserve Constable which can be part or full time positions. The ranks and their insignia correspond to those of other UK police services, with a few modifications. Sergeants' chevrons are worn point-up as is done in the United States, rather than point-down as is done in other police and military services of the United Kingdom. The six-pointed star & saltire device from the PSNI badge is used in place of the Crown in the insignia of superintendents, chief superintendents and the chief constable. The rank insignia of the chief constable, unlike those in other parts of the UK, are similar to those of the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis and the Commissioner of the City of London Police.

Data breaches

The PSNI suffered two data breaches in 2023.[64][65]

Following the 2023 data breaches, a LucidTalk opinion poll revealed that 38% of people in Northern Ireland had no confidence in the PSNI. The poll also found that unionist voters were more likely to have confidence in the police service than nationalists, though support for the PSNI was highest amongst "other" voters.[66]

See also

References

- Weitzer, Ronald. 1995. Policing Under Fire: Ethnic Conflict and Police-Community Relations in Northern Ireland (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press).

- Weitzer, Ronald. 1996. "Police Reform in Northern Ireland", Police Studies, v.19, no.2. pages:27–43.

- Weitzer, Ronald. 1992. "Northern Ireland's Police Liaison Committees", Policing and Society, vol.2, no.3, pages 233–243.

Footnotes

- "Funding in focus as Board approves PSNI Budget". NI Policing Board. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ONS Geography (8 January 2016). "The Countries of the UK". Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Police Service of Northern Ireland". nidirect. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- http://www.psni.police.uk/stations-2.pdf

- "Freedom of Information Request : Police Dogs Owned and/or Used by PSNI" (PDF). Psni.police.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Faisnéis as Gaeilge faoi Sheirbhís Póilíneachta Thuaisceart Éireann" (PDF). Police Service of Northern Ireland (in Irish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- Russell, Deacon (2012). Devolution in the United Kingdom. Edinburgh University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0748669738.

- "PSNI rehiring must be transparent". 3 October 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "Management of An Garda Síochána". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Gillespie, Gordon (2009). The A to the Z of the Northern Ireland Conflict. Scarecrow Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0810870451. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- McGoldrick, S.; McArdle, A. (23 July 2006). Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics. Springer. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4039-8331-2. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Dingley, James (13 October 2008). Combating Terrorism in Northern Ireland. Routledge. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-134-21046-6. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Mulcahy, Aogan (17 June 2013). Policing Northern Ireland. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-134-01995-3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "A New Beginning : Policing in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- McGoldrick, Stacey and McArdle, Andrea (2006). Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics. Palgrave Macmillan, p. 116. ISBN 1403983313

- Morrison, John F. (2013). Origins and Rise of Dissident Irish Republicanism: The Role and Impact of Organizational Splits. A&C Black, p. 189. ISBN 1623566770

- s.1, Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000

- "SF delegates vote to support policing". RTÉ News. RTÉ.ie. 28 January 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

The Sinn Féin decision in favour of supporting policing in Northern Ireland for the first time ever has been welcomed in Dublin, London and Belfast.

- "Police Pay Review". Police-information.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "PSNI: Jon Boutcher picked as interim chief constable". BBC News. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- "Committee A (Sovereign Matters) on Cross Border Cooperation between Police Forces" (PDF). British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly. July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013.

- "Freedom of Information Request : Human Resources" (PDF). Psni.police.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Hutchinson, Alan (31 May 2007). "Oversight Commissioner's final report notes continuing progress in policing change, but adds caution on future challenges" (Press release). Office of the Oversight Commissioner. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009.

- Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster (27 June 2000). "House of Commons Standing Committee B (pt 4)". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Response on the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000: Review of Temporary Recruitment Provisions" (PDF). Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2010.

- "Workforce Composition Figures | Police Service of Northern Ireland". Psni.police.uk. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Consultation Paper: Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000 –review of temporary recruitment provisions" (PDF). Northern Ireland Office. 30 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010.

- "Timeline of Irish dissident activity". BBC News. 20 April 2019. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

-

"PSNI allowed to use child informers". UTV News. u.tv. 1 September 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland policy, 'Children as Covert Human Intelligence Sources' was approved by Assistant Chief Constable Judith Gillespie in February 2005 as part of its child protection policy. In June 2009, Judith Gillespie was promoted to the rank of Deputy Chief Constable, the high rank obtained by a female.

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/crime

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/justice

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/local-policing

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/operational-support

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/people-and-organisational-development

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/strategic-planning-and-transformation

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/professional-standards-department

- https://www.psni.police.uk/about-us/our-departments/corporate-services

- "Tactical Support Group". www.psni.police.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "CAIN: The Patten Report on Policing: Summary of Recommendations, 9 September 1999". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. 9 September 1999. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Campbell, Niamh (31 January 2022). "PSNI officers wear brand new uniform for first time in 20 years". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- "Police Emblems and Flags Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2002". Opsi.gov.uk. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- McDonald, Henry (13 December 2007). "Belfast police forced back into flak jackets". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

-

Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

Unlike police forces in the rest of the United Kingdom, the PSNI is an armed force.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Freedom Of Information Request: F-2008-05034. Firearms held by PSNI" (PDF). PSNI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Top Cover issue 12". 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Freedom Of Information Request: F-2015-02781. Missing PSNI Firearms and Ammuniton" (PDF). PSNI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Freedom Of Information Request: F-2015-02038. Weapons" (PDF). PSNI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "Freedom of Information Request F-2012-00171 PSNI Issue weapons" (PDF). Police Service of Northern Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Jane's Police Review, 4 March 2007

- "Freedom Of Information Request: F-2017-00426 Negligent Discharges" (PDF). PSNI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Omega Foundation (March 2003). Baton Rounds - A review of the human rights implications of the introduction and use of the L21A1 baton round in Northern Ireland and proposed alternatives to the baton round (PDF). Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. ISBN 978-1903681336. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- "OVIK: CROSSWAY Armoured and Special Role Vehicles and Chassis". Oviks.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Penman" (PDF). Penman.co.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Freedom of Information Request : Use of Bicycles by PSNI" (PDF). Psni.police.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- PSNI (2015). April 2015, Keeping People Safe PSNI, Belfast.

- "Northern Ireland police service orders EC145 helicopter – CJI Main Site". Corporatejetinvestor.com. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Civil Aviation authority : Mark G-PSNR". Caa.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Keeping People Safe in Causeway Coast and Glens District" (PDF). PSNI. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "G-INFO G-BSWR". Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "£200k bill for 12th crash PSNI plane". Londonderry Sentinel. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018.

- "G-INFO G-CGTC". Civil Aviation Authority. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Freedom of Information Request : Blackberry Mobile Phones=Psni.police.uk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "PSNI confirms major data breach as Assistant Chief Constable apologises". TheJournal.ie. Press Association. 8 August 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- Edwards, Christian; Hauser, Jennifer (9 August 2023). "'Monumental' data breach exposes names of entire Northern Ireland police force". CNN. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- "Do you have confidence in (a) the PSNI?, and (b) the Chief Constable: Simon Byrne?". Twitter. Retrieved 22 August 2023.