Roman expansion in Italy

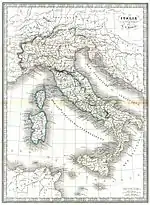

The Roman expansion in Italy covers a series of conflicts in which Rome grew from being a small Italian city-state to be the ruler of the Italian peninsula. Roman tradition attributes to the Roman kings the first war against the Sabines and the first conquests around the Alban Hills and down to the coast of Latium. The birth of the Roman Republic after the overthrow of the Etruscan monarch of Rome in 509 BC began a series of major wars between the Romans and the Etruscans. In 390 BC, Gauls from the north of Italy sacked Rome. In the second half of the 4th century BC Rome clashed repeatedly with the Samnites, a powerful tribal coalition of the Apennine region.

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

By the end of these wars, Rome had become the most powerful state in central Italy and began to expand to the north and to the south. The last threat to Roman hegemony came during the Pyrrhic war (280–275 BC) when Tarentum enlisted the aid of the Greek king Pyrrhus of Epirus to campaign in the North of Italy. Resistance in Etruria was finally crushed in 265–264 BC, the same year the First Punic War began and brought Roman forces outside of the peninsula for the first time. Starting from the First Punic War (264–241 BC) the territories subject to Roman rule also included Sicily (241 BC), Sardinia and Corsica (238 BC), islands transformed into provinces.

Later, in conjunction with the Second Punic War (218–202 BC), Rome also proceeded to subjugate the Celtic territories north of the Apennines of Cisalpine Gaul (from 222 to 200 BC) and then of the neighboring populations of Veneti (to the east) and Ligures (to the west) until reach the foothills of the Alps. With the end of the period of civil wars (44–31 BC), Augustus undertook the conquest of the Alpine valleys (from the Aosta Valley to the Arsia river in Istria) from 16 BC to 7 BC completing the conquest of the Italian geographical region. Following the conquest of the entire Alpine arc, and with it the entire Italian territory, he divided Italy into 11 regions (about 7 AD). Conquered territories were incorporated into the growing Roman state in a number of ways: land confiscations, the establishment of coloniae, granting of full or partial Roman citizenship and military alliances with nominally independent states. The successful conquest of Italy gave Rome access to a manpower pool unrivaled by any contemporary state and paved the way to the eventual Roman interference of the entire Mediterranean world.

Background

The name of ancient peoples of Italy indicates those populations settled in the Italian peninsula during the Iron Age and before the Roman expansion and conquest of Italy. Many of the names are either scholarly inventions or exonyms assigned by the ancient writers of works in ancient Greek and Latin.

In regard to the specific names of particular ancient Italian tribes and peoples, the time-window in which historians know the historical ascribed names of ancient Italian peoples mostly falls into the range of about 750 BC (at the legendary foundation of Rome) to about 200 BC (in the middle Roman Republic), the time range in which most of the written documentation first exists of such names and prior to the nearly complete assimilation of Italian peoples into Roman culture.

Nearly all of these peoples and tribes spoke Indo-European languages: Italics, Celts, Ancient Greeks, and tribes likely occupying various intermediate positions between these language groups. On the other hand, some Italian peoples (such as the Rhaetians, Camuni, Etruscans) likely spoke non- or pre-Indo-European languages. In addition, peoples speaking languages of the Afro-Asiatic family, specifically the largely Semitic Phoenicians and Carthaginians, settled and colonized some coastal parts of Italy (particularly in insular Italy in western and southern Sardinia and western Sicily).[1]

Some scholars believe that many peoples spoke non-Indo-European languages. Some of them were Pre-Indo-Europeans or Paleo-Europeans while, with regard to some others, Giacomo Devoto proposed the definition of Peri-Indo-European (i.e. everything that has hybrid characters between Indo-European and non-Indo-European).[2]

Roman conquest of Latium vetus (753-341 BC)

The most ancient history, from the foundation of Rome as a small tribal village,[3] until the end of the Royal Age with the fall of the kings of Rome, is the least preserved.[4][5] Although Livy, a Roman historian, in his work Ab Urbe condita, lists a series of seven kings of archaic Rome, from the first settlement up to the first years, the first four 'kings' (Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius and Ancus Martius) are almost certainly entirely apocryphal.[6] Historians hypothesize that, prior to the establishment of Etruscan rule over Rome under Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of tradition,[6] Rome had been led by some sort of religious authority.[7] According to tradition, Romulus fortified one of seven hills of Rome, the Palatine Hill, after founding the city, and Livy claims that, shortly after its foundation, Rome was "equal to any of the surrounding cities in military prowess".[8]

Under the Etruscan kings Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus, Rome expanded in a northwesterly direction, coming into conflict against the Veientani (northeast of the Tiber) after the expiration of the treaty that ended the previous war.[9] Tarquinius Priscus fought the Sabines (in about 585/584 BC), as did his successor Servius Tullius.[10] Again Priscus obtained a triumph over the Latins (he bought the cities of Corniculum and Collatia from the Roman state)[11][12] and the Etruscans (on 1 April 588/587 BC).[13] Servius Tullius also obtained a double triumph over the latter (on 25 November 571/570 BC and on 25 May 567/566 BC).[13] And finally Strabo recalls that Tarquinius Priscus always destroyed numerous cities of the Aequi.[14] The last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, was the first to fight the Volsci[13][15][16] and then subdued numerous cities of Latium vetus, making peace with the Etruscans.[15] Eventually the Etruscan kings were overthrown in the context of a wider disempowerment of Etruscan power in the region during the same period, and Rome, whose possessions did not extend beyond 15 miles from the city,[15] gave itself a republican set-up.[17][18]

With the beginning of this new historical phase, the immediate neighbors of Rome were cities or villages of the Latins, with a tribal structure similar to that of Rome, or even Sabine tribes of the nearby Apennine hills.[19] Gradually Rome defeated both the Sabines and the local cities which were either hegemonized by the Etruscans or Latin cities which, like Rome, had rid themselves of their Etruscan rulers.[19] Rome defeated the Lavinii and the Tusculi in the battle of Lake Regillus, 496 BC,[20] and the Sabines in an unknown battle in 449 BC,[20] the Aequi and the Volsci in the battle of Mount Algidus in 458 BC and in the battle of Corbio in 446 BC, the Volsci in the battle of Corbione[21] and in the conquest of Anzio in 377 BC,[22] the Aurunci in the battle of Ariccia;[23] they were defeated by the Veientani in the battle of the Cremera in 477 BC,[24] in the conquest of Fidene in 435 BC[25] and in the veient wars that led to the conquest of Veii in 396 BC.[25] Once the Veientani had been defeated, the Romans had effectively completed the conquest of their immediate Etruscan neighbors,[26] and, at the same time, secured their position against the immediate threat posed by the tribal peoples of the Apennine hills.

Rome, however, still controlled only a very small area and its business played a minor role in the entire context of the Italian peninsula: the remains of Veii, for example, today fall entirely within the suburbs of modern Rome[21] and Rome's interests came to the attention of the Greeks, bearers of the leading culture of the time.[27] The bulk of Italy still remained in the hands of the Latins, the Sabines, the Samnites and other peoples of central Italy, the Greek colonists of the Magna Graecia poleis, and, in particular, the Celtic peoples of northern Italy, including the Gauls.

At the time, Celtic civilization was vibrant and in the process of military and territorial expansion, with a spread that, although lacking in cohesion, came to cover much of continental Europe. It was precisely at the hands of the Celts of Gaul that Rome suffered a humiliating defeat, which was followed by a setback imposed on its expansion: the memory of that defeat was destined to imprint itself deeply on the conscience and future memory of Rome. From 390 BC, many Gallic tribes had begun to invade Italy from the north, unbeknownst to the Romans whose interests still turned to security on an essentially local scenario. Rome was alerted by a particularly warlike tribe,[27] the Senones, who invaded the Etruscan province of Siena from the north and attacked the city of Clusium (Chiusi),[28] not far from the sphere of Roman influence. The inhabitants of Chiusi, overwhelmed by the strength of their enemies, superior in number and ferocity, asked Rome for help. Almost unintentionally[27] the Romans not only found themselves in conflict with the Senones, but they became their main target.[28] The Romans faced them in the battle of the Allia[27] around the years 390–387 BC. The Gauls, led by the leader Brennus, defeated a Roman army of about 15,000 soldiers[27] and pursued the fugitives right into the city itself, which was subjected to a partial but humiliating sack[29][30] before being driven out[29] or convinced to leave on payment of a ransom.[27][28]

The hegemony over central-southern Italy (343-264 BC)

.JPG.webp)

The stages of the Roman conquest, after having achieved hegemony over Latium vetus was to expand first towards the south (Samnite Wars) and then towards the north (Roman–Etruscan Wars) until obtaining total domination of the Italian peninsula from the Arno to the strait of Messina during the first republican period (until 264 BC).

After recovering from the sack of Rome,[31] the Romans immediately resumed their expansion into Italy. Despite the successes obtained up to then, control over the entire peninsula was not, at that point, in any way assured: the Samnites were just as warlike and rich as the Romans;[32] moreover, for their part, they set out to expand from the original Samnium to secure new lands in those fertile Italian plains on which Rome itself insisted.[33] The First Samnite War, between 343 and 341 BC, followed widespread Samnite incursions into the territory of Rome,[34] which were followed by both the battle of Mount Gaurus (342 BC), and the battle of Suessula (341 BC), where the Romans defeated the Samnites but were forced to withdraw from the war without being able to exploit the success to the fullest, due to the revolt of many of the Latin allies in the conflict known as the Latin War.[35][36] In this way Rome, around 340 BC, found itself having to contain both the Samnite incursions into its territory and those of the rebellious Latin cities, with which it engaged in a bitter conflict. Eventually the Latins were defeated at the battle of Vesuvius and again at the battle of Trifanum,[36] after which the Latin cities were forced to submit to Roman power.[37][38]

The Second Samnite War, from 327 to 304 BC, represented a more serious and lengthy affair, both for the Romans and for the Samnites,[39] the conclusion of which required more than 20 years of conflict, and 24 battles, at the price of very serious losses for both sides. The alternating fortunes of the conflict smiled both on the Samnites and on the Romans; the former took possession of Naples in 327 BC,[39] which the Romans recovered before being defeated in the battle of the Caudine Forks[39][40] and at the battle of Lautulae. The Romans finally emerged victorious from the battle of Bovianum (305 BC), when by now, as early as 314 BC, the tide of the war was turning decisively in Rome's favor, forcing the Samnites to negotiate the surrender on increasingly unfavorable terms. In 304 BC the Romans came to a massive annexation of Samnite territories, on which they even founded many of their colonies. But seven years after their defeat, while Rome's dominance over the area seemed secure, the Samnites rose again and defeated the Romans at the battle of Camerinum, in 298 BC, which started the Third Samnite War. Strengthened by this success, they tried to put together a coalition of many of the populations that had once been hostile to Rome, to prevent Rome from dominating the whole of central and southern Italy. The army that in 295 B.C. faced the Romans at the battle of Sentinum[40] included a motley coalition of Samnites, Gauls, Etruscans and Umbri.[41] When the Roman army won a convincing victory even over these combined forces, it became clear that nothing more could prevent Rome from dominating Italy. And with the subsequent battle of Populonia, in 282 BC, Rome put an end to the last vestiges of Etruscan hegemony over the region. The Roman victory in the three Samnite Wars (343–341; 326–304; 298–290 BC) therefore ensured the control of a large part of central-southern Italy for the City; the political and military strategies implemented by Rome, such as the foundation of colonies under Latin rights, the deduction of Roman colonies and the construction of the Appian Way, testify to the power of this expansionist push towards the South.[42] The interest in territorial domination was in fact not a simple prerogative of some aristocratic families, including the Claudia gens, but invested the entire Roman political scene, and the entire Roman Senate adhered to it together with the plebeians.[42] In fact, the advance towards the South was stimulated by economic and cultural interests; while the presence of a civilization, that of Magna Graecia, with a high level of military, political and cultural organization, capable of resisting Roman expansion, contributed to slowing it down.[43]

With the beginning of the third century, Rome was found to be a great power of the peninsular chessboard, but had not yet entered into friction with the dominant Mediterranean powers of the time, Carthage and the poleis of Greece. Rome had defeated all the most important Italian populations (Etruscans and Samnites) and dominated the allied Latin cities. However, southern Italy still remained in the hands of the colonies of Magna Graecia[44] which had been allies of the Samnites and with which it would inevitably come into conflict as a result of its continuous expansion.[45][46]

It is not possible to determine with precision what were the commercial relations that united Rome with the centers of Magna Graecia, but a certain sharing of commercial interests between Rome and the Greek cities of Campania is probable, as evidenced by the issue, starting from 320 BC, of Roman-Campanian coins.[47] However, it is not clear whether these commercial agreements were the factor or the product of the Samnite wars and of the Roman expansion towards the South, and it is therefore not possible to determine what was the actual weight of the negotiators in the expansionist policy, at least until the second half of the 3rd century BC.[48] However, the needs of the rural populace also determined the need for territorial expansion towards the south, which required new arable lands that the expansion in central and northern Italy had not been sufficient to provide.[48]

When a diplomatic dispute between Rome and the Greek colony of Taranto[49] resulted in open naval conflict with the battle of Thurii,[46] Taranto invoked the military aid of Pyrrhus, king of the Molossians of Epirus.[46][50] Driven by his diplomatic ties with Taranto, and by personal ambition,[51] Pyrrhus landed on Italian soil in 280 BC,[52] who was joined by some from the Greek colonies and with that part of the Samnites who had revolted against Roman control. Despite a series of defeats remedied by the Roman army, starting from the battle of Heraclea in 280 BC,[46][53] and then in the battle of Asculum in 279 BC,[53][54] Pirro realized that his location in Italy was unsustainable. Rome, during the permanence of Pyrrhus' army in Italy, always and intransigently refused any negotiation.[55]

Meanwhile, Rome was concluding a new treaty with Carthage, and Pyrrhus, against all his expectations, found that none of the other Italic peoples would defect to the cause of the Greeks and Samnites.[56] Faced with a victory with unacceptable losses, for which the term "Pyrrhic victory" would be coined, in each of the clashes with the Roman army, and in the impossibility of widening the front of the alliances in Italy, Pyrrhus withdrew from the Italian peninsula and he turned to Sicily against Carthage,[57] leaving his allies to face the Roman army.[45] When the Sicilian campaign also proved a failure Pyrrhus, also at the request of his Italian allies, returned to the continent to compete once again with Rome. In 275 BC, Pyrrhus once again faced the Roman army at the battle of Beneventum.[54] But Rome had devised new tactics to deal with the war elephants, including the use of pilum,[54] fire,[57] or, as one source states, simply slamming the elephants' heads. The outcome of the battle, although not decisive,[57] made Pyrrhus aware of how impoverished and tried by his army by years of campaigns in foreign lands: the hope of future victories having gone away in his eyes, the Epirote king completely abandoned the 'Italy. Taranto, on the other hand, was besieged again in 275 BC and forced to surrender in 272 BC. Rome was thus the hegemonic power in peninsular Italy, south of the Ligurian and Tuscan-Emilian Apennines.

The Pyrrhic Wars would have had a great effect on Rome, which now proved capable of measuring its military power with that of the hegemonic powers of the Mediterranean. Rome moved rapidly into southern Italy, subjugating and dividing Magna Graecia.[58] Having established an effective dominion over the Italian peninsula,[59] and on the strength of its military reputation,[60] Rome was able to start looking beyond, to aim at expanding outside the Italian peninsula. Considered the natural barrier of the Alps to the north, and still not wanting to compete in battle with the proud Gallic peoples, the city turned its gaze elsewhere, to Sicily and the Mediterranean islands, a political line that would have brought it into open conflict with its former ally, the city of Carthage.[60][61]

The conquest of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and Cisalpine Gaul (264–133 BC)

Starting then from the First Punic War (264–241 BC) the territories subject to Roman rule also included Sicilia (241 BC), Sardinia and Corsica (238 BC). Even in the third century BC, even though Rome's conquest of Italy was almost complete, there was no feeling of common belonging. It was the Second Punic War (218–202 BC) that laid the foundations. When the Punic general Hannibal attacked the city of Sagunto, an ally of Rome, but south of the Ebro river, in 219 BC, the Roman Senate declared war on Carthage, after some hesitation. It was the beginning of the Second Punic War. The Greek historian Polybius disputed the causes of the war that the Latin historian Quintus Fabius Pictor would have identified in the siege of Saguntum and in the passage of the Carthaginian armies of the Ebro. He believed that these were only two events that led to the start of the war, but not its root causes.[62] War was inevitable,[63] but as Polybius writes, the war did not take place in Iberia [as the Romans hoped] but right at the gates of Rome and throughout Italy.[64]

After the final defeat of Hannibal in the battle of Zama (202 BC), the Romans took revenge on the peoples who, despite being subjected to Rome, had rebelled and joined forces with Carthage. Some cities in southern Italy were razed to the ground, while the few remaining Gauls in Cispadane Gaul were completely annihilated. The Roman army, which had gone beyond the Po river shortly before the beginning of the "Hannibalic war", had conquered part of the territories of Cisalpine Gaul. The battle of Clastidium, in 222 BC, earned Rome the capture of the Insubres' capital of Mediolanum (Milan). In order to consolidate its dominion, Rome created the colonies of Piacenza, in the territory of the Boii, and Cremona in that of the Insubres. The Gauls of northern Italy had therefore rebelled following Hannibal's descent into Italy from the Alps, but after Zama they were definitively subdued by Rome. During the Second Punic War, Rome also subjugated the Celtic territories north of the Apennines of Cisalpine Gaul (from 222 to 200 BC) and then those of the neighboring Veneti (to the east) and the Ligures (to the west) before reaching the base of the Alps. In 200 BC, the Gauls in revolt took possession of the colony of Piacenza and threatened Cremona, but Rome decided to intervene in force. In 196 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica defeated the Insubres, and in 191 BC, the Boii, who controlled a vast area between Piacenza and Rimini, were defeated. After crossing the Po river, the Roman penetration continued peacefully; the local populations, Cenomani and Veneti, realized that Rome was the only power capable of protecting them from the assaults of the other neighboring tribes. Around 191 BC Cisalpine Gaul was definitively occupied. The advance also continued in the north-eastern part with the foundation of the Roman colony of Aquileia in 181 BC, as the ancient authors recount,[65] in the territory of the ancient Carni.[66][67] In 177 BC Istria was subjugated and in 175 BC the Cisalpine Ligures were also subjugated. A few decades later, Polybius could personally testify to the decline of the Celtic population in the Po valley, expelled from the region or confined to some limited subalpine areas.[68]

Thus many tribal groups, both in the north and in the south, were forcibly uprooted from their native country and deported elsewhere.[69] The Ligurian Apuans, for example, were deported en masse (47,000 people) to Sannio and Campania. The process of Romanization and homogenization of the peninsula began to bear fruit at this point. In the south, for example, the Italian aristocrats began to organize mixed marriages with the Roman and Etruscan aristocracies, in order to create conjugal relationships that led to blood ties throughout the peninsula. This was so successful that, starting from the 1st century BC, numerous prominent political figures could count Etruscan, Samnite, and Umbrian families and so on among their ancestors.[70]

The socii rebel and ask for Roman citizenship (133–42 BC)

The period from the Gracchan agitations (133–121 BC) to the domination of Sulla (82–78 BC), marked the beginning of the crisis which, almost a century later, ended the aristocratic republic. Historian Ronald Syme has called the period of transition from the Republic to the Augustan principate the "Roman Revolution".[72]

The Republic's rapid expansion in the Mediterranean basin led to huge problems as until then, the Roman institutions had been designed to administer a small state, but the state now stretched from Iberia to Africa, Greece, and Asia Minor. In 133 BC, the tribune of the plebs Tiberius Gracchus was concerned by the shortage of manpower in various parts of Italy and by the widespread poverty. He was convinced that in these conditions it would have been impossible to maintain the social order which was the backbone of the army. So he proposed to distribute excess land to less well-off citizens, giving new vigor to the class of small agricultural owners, which was in serious difficulty due to the continuous wars. He was opposed by large landowners, who extended their domains through the eviction of debtor settlers or the purchase of their land.[73] The constant wars at home and abroad forced the small landowners to abandon their farms for many years to serve in the legions; but they supplied Rome (by means of looting and conquests) with an enormous quantity of cheap goods[74] and slaves, who were usually employed in the farms of the wealthy, with huge consequences for the Roman social fabric, as small landed property could not compete with the slave estates, with their low running costs. All those families who, due to debts, had been forced to leave the countryside, took refuge in Rome, where they formed an urban underclass; a mass of people who had no job, no home and no food to eat, with the inevitable and dangerous social tensions in the Italian world.

After these events, Roman Italy was affected by the Cimbrian Wars (113–101 BC). The Germanic tribes of the Cimbri and Teutons from Northern Europe migrated into Rome's northern territories,[75] and came into conflict with Rome and its allies.[76] This was alarming given the history of the invasion of the Gauls in 390 BC and the "Hannibalic war"; so much so that Italy and Rome itself felt seriously threatened.[76] In 105 BC the Romans suffered one of their worst defeats in the battle of Arausio, near Orange in Transalpine Gaul; it was a tremendous defeat, almost equal to that of the battle of Cannae. After the Cimbri granted a truce to the Romans to devote themselves to the plunder of Iberia, Rome was able to carefully prepare for the final battle against these Germanic populations, managing to exterminate them first in the battle of Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) and then in the battle of Vercellae, on Italian soil.[75] The tribes were beaten and enslaved (at least 140,000 captives) and their threat removed.[77]

With the second half of the 2nd century BC the Italics without Roman citizenship (socii) began to ask for citizenship, which they however obtained after a hard and bloody social war in 89 BC. It was the last and fundamental step of the Italian integration into the Roman world, and therefore of the consequent fusion of the various ethnic cultures into a single political and cultural identity. The Italics without citizenship coalesced against Rome (Velleius Paterculus even writes "all of Italy rose up against Rome"[78]) and, if on the one hand the Italian coalition lost the war, it also obtained the longed-for Roman citizenship.[79] It was at the end of this "great war" (as Diodorus Siculus[80] defined it), that the differences between Italy and the provinces became more evident.

Simultaneously with all these events, in the years between 135 and 71 BC, there were servile uprisings in Sicily and then on Italian soil, which opposed the slaves to the Roman state. The third uprising was the most serious.[81] Estimates of the number of rioters speak of the involvement of a number of 120,000 or 150,000 slaves.[82] In this last revolt, Spartacus, leading the rebels, had been trained as a gladiator. In 73 BC, together with some companions, he rebelled against Capua and fled towards Vesuvius. The number of rebels quickly grew to 70,000, composed mainly of Thracian, Gaul and Germanic slaves. Initially, Spartacus and his second-in-command Crixus managed to defeat several legions sent against them. Once a unified command was established under Marcus Licinius Crassus, who had six legions, the rebellion was crushed in 71 BC. About 10,000 slaves fled the battlefield. The fleeing slaves were intercepted by Pompey, aided by the pirates who had initially promised to transport them to Sicily but then betrayed them, presumably on the basis of an agreement with Rome, which was returning from Spain, and 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way, from Capua to Rome.[83]

Many historians agree that the Roman civil wars, mostly fought on Italian soil, were a logical consequence of a long process of decline of Rome's political institutions, which began with the murders of the Gracchi in 133 and 121 BC.[84] and continue with the reform of the legions of Gaius Marius, who was the first to hold many extraordinary public positions inaugurating an example that would be followed by the future aspiring dictators of the decadent republic, the social war, the clash between Marians and Sullans which ended with the establishment of the dictatorship of Sulla, known for the proscription lists issued in its course, and finally in the First Triumvirate.[85] These events shattered the foundations of the Republic.

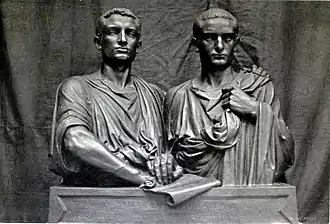

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

After bitter disagreements with the senate, Caesar crossed the Rubicon river in arms, which marked the border between the province of Cisalpine Gaul and the territory of Italy;[86] the senate, on the other hand, rallied around Pompey and, in an attempt to defend the republican institutions, decided to declare war on Caesar (49 BC). That same year, citizenship was also extended to the Cisalpine Gauls and the Veneti through the Lex Roscia, crowning the long-awaited social integration of the entire Italian peninsula, effectively becoming all Italics, Romans to all intents and purposes.[87]

Meanwhile, after ups and downs, Cesariani and Pompeiani faced each other in the battle of Pharsalus, where Cesare irreparably defeated his rival. Pompey then sought refuge in Egypt, but was killed there (48 BC). Caesar also went to Egypt, and there he became involved in the dynastic dispute that broke out between Cleopatra and his brother Ptolemy XIII. Once the situation was resolved, he resumed the war, and defeated the king Pharnaces II of Pontus in the battle of Zela (47 BC). He therefore left for Africa, where the Pompeians had reorganized under the command of Cato, and defeated them in the battle of Thapsus (46 BC). The survivors found refuge in Spain, where Caesar joined them and defeated them, this time definitively, in the battle of Munda (45 BC).

Caesar died following a conspiracy on the Ides of March (44 BC) and his nephew Octavian became his main heir. Informed of the killing of his great-uncle, he decided to return to Rome to claim his rights as an adopted son, as well as that of boasting, as the only adopted son, the name of the deceased, thus becoming Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian. Caesar also left the inhabitants of Rome 300 sesterces each, in addition to his gardens along the banks of the Tiber (Horti Caesaris).[88] Having landed in Brindisi,[89] Octavian arrived in Rome on 21 May, after the caesaricides had already left the city for more than a month. The young man hastened to claim the adoptive name of Gaius Julius Caesar, publicly declaring that he accepted his father's inheritance and therefore asking to take possession of the family assets. The Senate, and in particular Cicero, who saw him at that moment as an inexperienced beginner given his young age,[90] ready to be manipulated by the senatorial aristocracy, and who appreciated the weakening of Antony's position, approved the ratification of the will. With Caesar's patrimony now at his disposal, Octavian was able to recruit a private army of about 3,000 veterans, while Mark Antony, having obtained the assignment of Cisalpine Gaul already entrusted to the proprietor Decimus Brutus, was preparing to wage war on the Caesaricides to regain favor of the Caesarian faction. On this occasion Cicero wrote to Titus Pomponius Atticus demonstrating certainty about Octavian's fidelity to the republican cause, certain of the possibility of exploiting the potential of that young scion to eliminate Antony,[91] who emerged unscathed (to the orator's grave displeasure) from the Ides.[92]

And while a new civil war was underway, two years after the death of Caesar (42 BC), the new province of Cisalpine Gaul was abolished and Roman Italy came to incorporate all the territories south of the Alps, and became fully part of Italy, even if its cities had already obtained Roman citizenship from Caesar seven years earlier.[87]

From Philippi (42 BC) to the Augustan reorganization (7 AD)

After the victory of Octavian and Antony in the battle of Philippi (42 BC), new contrasts arose between the two. Lucius Antonius, brother of Antony, in 41 BC rebelled against Octavian because he demanded that even his brother's veterans were distributed lands in Italy (in addition to Octavian's 170,000 veterans), but he was defeated in Perugia in 40 BC. Suetonius recounts that during the siege of Perugia, while he was making a sacrifice not far from the city walls, Octavian was nearly killed by a group of gladiators who had made a sortie from the city.[94] After Lucius Antonius' defeat,[94] both Antonius and Octavian decided not to give too much weight to the incident.[95] Eventually even the soldiers of both sides refused to fight and the triumvirs put their strife aside. With the treaty of Brindisi (September 40 BC) there was a new division of the provinces as Antony was left with the Roman East from Scutari, including Macedonia and Achaia; to Octavian the West including Illyricum; to Lepidus, now out of the power games, Africa and Numidia; Sicilia was confirmed to Sextus Pompey to silence him, so that he would not cause problems in the West.[95] The pact was sanctioned with the marriage between Antony, whose wife Fulva had recently died, and Octavian's sister, Octavia the Younger.

In 38 BC, Octavian resolved to meet in Brindisi with Antony and Lepidus to renew the alliance pact for another five years. In 36 BC, however, due to his friend and general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Octavian managed to put an end to the war with Sextus Pompey. The latter, due also to some reinforcements sent by Antonio, was in fact definitively defeated in the battle of Naulochus.[96] Sicily fell and Sextus Pompey fled to the East, where he was shortly afterwards assassinated by Antonius' assassins.[95] At that point, however, Octavian had to face the ambitions of Lepidus, who believed that Sicily should be his turn and, breaking the alliance pact, moved to take possession of it with 20 legions. However, quickly defeated, after his soldiers abandoned him by going over to Octavian's side, Lepidus was finally confined to the Circeo, while retaining the public office of pontifex maximus.[96]

After the gradual elimination of all contenders over six years, from Brutus and Cassius, to Sextus Pompeius and Lepidus, the situation remained in the sole hands of Octavian, in the West, and Antony, in the East, leading to an inevitable increase in contrasts between the two triumvirs. Conflict was now inevitable. Only the casus belli was missing, which Octavian found in Antony's will, in which his decision to leave the eastern territories of Rome to Cleopatra of Egypt and her children, including Caesarion, son of Caesar, were recorded.[97] Later, when it had Antony declared a public enemy, the Senate of Rome declared war on Cleopatra, the last Ptolemaic queen of Egypt, in late 32 BC, Antony and Cleopatra were defeated at the battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BC and both committed suicide the following year in Egypt.[97][98]

Octavian had become, in fact, the absolute master of the Roman state, even if formally Rome was still a republic and Octavian himself had not yet been invested with any official power, given that his potestas of triumvir had never been renewed: in the Res Gestae Divi Augusti acknowledges having governed in recent years by virtue of the "potitus rerum omnium per consensum universorum" ("general consensus"), having for this reason received a sort of perpetual tribunicia potestas[99] (certainly an extra-constitutional fact).[100] As long as this consensus continued to include the loyal support of armies, Octavian could govern safely, and his victory constituted, in fact, Italy's victory over the Near East; the guarantee that the Roman Empire would never have been able to find its equilibrium and its center elsewhere than Rome.

With the end of the period of civil wars, Octavian Augustus undertook the conquest of the Alpine valleys (from the Aosta Valley to the river Arsia in Istria) from 16 BC to 7 BC completing the conquest of the Italian geographical region. Following the conquest of the entire Alpine arc, and with it the entire Italian territory, he divided Italy into 11 regions, enriching it with new centers (about 7 AD).[101] The regions in question were as follows:

- Regio I Latium et Campania

- Regio II Apulia et Calabria

- Regio III Lucania et Bruttium

- Regio IV Samnium

- Regio V Picenum

- Regio VI Umbria et Ager Gallicus

- Regio VII Etruria

- Regio VIII Aemilia

- Regio IX Liguria

- Regio X Venetia et Histria

- Regio XI Transpadana

Suetonius and the Res gestae divi Augusti speak of the foundation of as many as 28 colonies.[102] It recognized, in a certain way, the importance of these colonies, attributing rights equal to those of Rome, allowing the decurions of the colonies to vote, each in their own city, for the election of the magistrates of Rome, sending their vote in Rome, on election day.[102]

Augustus strengthened the hegemonic position of the Italian peninsula and its Roman and Italic traditions. Throughout the first century, Italy enjoyed unequaled prestige, strong economic and juridical privileges due to the Ius Italicum which distinguished Italian soil from the Solum provinciale, and a hegemonic position at a military as well as an economic level within the Mediterranean Sea. Among the privileges of Italy there was also the construction of a dense road network, the embellishment of the cities by equipping them with numerous public structures (forums, temples, amphitheaters, theaters and baths)[103] and tax collection offices.[102]

As Roman provinces were being established throughout the Mediterranean, Italy maintained a special status which made it domina provinciarum ("ruler of the provinces"),[104][105][106] and – especially in relation to the first centuries of imperial stability – rectrix mundi ("governor of the world")[107][108] and omnium terrarum parens ("parent of all lands").[109][110] Such a status meant that, within Italy in times of peace, Roman magistrates also exercised the imperium domi (police power) as an alternative to the imperium militiae (military power). Italy's inhabitants had Latin Rights as well as religious and financial privileges.

References

- "Sicilian Peoples: The Carthaginians". Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Giacomo Devoto, Gli antichi Italici, Firenze, Vallecchi, 1931.

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 3, par. 8

- Grant 1993, p. 23

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 3

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 5, par. 1

- Grant 1993, p. 21

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, I, 9.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, I, 42.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, I, 7.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.19.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.37.

- Fasti Triumphales

- Strabo, Geographica, V, 3.4.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, I, 8.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.25 and 1.44.

- Grant 1993, p. 31

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 6, par. 1

- Grant 1993, p. 38

- Grant 1993, p. 37

- Matyszak 2004, p. 13

- Grant 1993, p. 39

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, II, 26

- Grant 1993, p. 41

- Grant 1993, p. 42

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 2

- Grant 1993, p. 44

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 2

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, V, 48

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 283

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 4

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 23

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 282

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 8

- Grant 1993, p. 48

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 13

- Grant 1993, p. 49

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 9, par. 14

- Grant 1993, p. 52

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 290

- Grant 1993, p. 53

- Musti 1990, p. 533

- Musti 1990, p. 534

- Grant 1993, p. 77

- Matyszak 2004, p. 14

- Grant 1993, p. 78

- Musti 1990, p. 535

- Musti 1990, p. 536

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 294

- Cantor 2004, p. 151

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 10, par. 6

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 304

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 305

- Grant 1993, p. 79

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, I, 7.3.

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 10, par. 11

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 306

- Lane Fox 2005, p. 307

- Pennell 1890, chpt. 11, par. 1

- Grant 1993, p. 80

- Matyszak 2004, p. 16

- Polybius, The Histories, III, 6.1-3.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, III, 7.

- Polybius, The Histories, III, 16.6.

- Velleius Paterculus, Historiae Romanae ad M. Vinicium consulem libri duo, I, 13.2.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, III, 126-127.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, XL, 34.2-3.

- Polybius, Histories, II, 35.4.

- Robson 1934, pp. 599–608

- David 2002, p. 43

- Sturgis, Russell (1904). The appreciation of sculpture: a handbook. New York: Baker. p. 146.

- Ruffolo 2004, p. 72

- Ruffolo 2004, p. 18

- Ruffolo 2004, p. 17

- Matyszak 2004, p. 75

- Santosuosso 2001, p. 6

- Le Glay, Voisin & Le Bohec 2002, p. 111

- Velleius Paterculus, Historiae Romanae ad M. Vinicium consulem libri duo, II, 15.

- Strabo, Geographica, V, 1.1.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, XXXVII, 1.

- Matyszak 2004, p. 77

- Santosuosso 2001, p. 43

- Matyszak 2004, p. 133

- Sheppard & Hook 2010, p. 8

- Sheppard & Hook 2010, pp. 9–10

- Sheppard & Hook 2010, p. 16

- Laffi 1992, pp. 5–23

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Caesar, 68.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 10.

- Cicero, Philippicae, XIII.

- Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, XV, 12.2.

- Canfora 2007, pp. 72–73

- "LaGrandeBiblioteca.com is available at DomainMarket.com". LaGrandeBiblioteca.com is available at DomainMarket.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 14.

- Wells 1995

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 16.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 17.

- Chamoux 1988, pp. 254 and following

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 27.

- Mazzarino 1973, pp. 68 and following

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, III, 46.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 46.

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Augustus, 30.

- A. Fear; P. Liddel, eds. (2010). "The Glory of Italy and Rome's Universal Destiny in Strabo's Geographika". Historiae Mundi. Studies in Universal History. London: Duckworth. pp. 87–101. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Keaveney, Arthur (January 1987). Arthur Keaveney: Rome and the Unification of Italy. ISBN 9780709931218. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Billanovich, Giuseppe (2008). Libreria Universitaria Hoepli, Lezioni di filologia, Giuseppe Billanovich e Roberto Pesce: Corpus Iuris Civilis, Italia non erat provincia, sed domina provinciarum, Feltrinelli, p.363 (in Italian). ISBN 9788896543092. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Bleicken, Jochen (15 October 2015). Italy: the absolute center of the Republic and the Roman Empire. ISBN 9780241003909. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Morcillo, Martha García (2010). "The Roman Italy: Rectrix Mundi and Omnium Terrarum Parens". In A. Fear; P. Liddel (eds.). Historiae Mundi. Studies in Universal History. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781472519801. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Altri nomi e appellativi relazionati allo status dell'Italia in epoca romana (in Italian). Bloomsbury. 20 November 2013. ISBN 9781472519801. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- "Antico appellativo dell'Italia romana: Italia Omnium Terrarum Parens" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 November 2021.

Bibliography

- Canfora, Luciano (2007). La prima marcia su Roma (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-8368-9.

- Cantor, Norman Frank (2004). Antiquity. Perennial Press. ISBN 0-06-093098-5.

- Chamoux, François (1988). Marco Antonio: ultimo principe dell'oriente greco (in Italian). Milan: Rizzoli. ISBN 88-18-18012-6.

- David, Jean-Michel (2002). La Romanizzazione dell'Italia (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 978-8842064138.

- Fulminante, Francesca (2023). The rise of early Rome: transportation networks and domination in central Italy, 1050-500 BC. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316516805.

- Grant, Michael (1993). The History of Rome. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-11461-X.

- Laffi, Umberto (1992). "La provincia della Gallia Cisalpina". Athenaeum (in Italian). Vol. 80. Università di Pisa.[ISBN unspecified]

- Lane Fox, Robin (2005). The Classical World. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-102141-1.

- Le Glay, Marcel; Voisin, Jean-Louis; Le Bohec, Yann (2002). Storia romana (in Italian). Il Mulino. ISBN 978-8815087799.

- Musti, Domenico (1990). "La spinta verso il Sud: espansione romana e rapporti "internazionali"". Storia di Roma. Vol. I. Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-11741-2.

- Pennell, Robert Franklin (1890). Ancient Rome: From the earliest times down to 476 A.D. Riverside, California: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1165311828.

- Matyszak, Philip (2004). The Enemies of Rome. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-25124-X.

- Mazzarino, Santo (1973). L'impero romano (in Italian). Bari: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-2377-9.[ISBN unspecified]

- Robson, D.O. (1934). "The Samnites in the Po Valley". The Classical Journal. 29 (8).

- Ruffolo, Giorgio (2004). Quando l'Italia era una superpotenza (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17514-6.

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2001). Storming the Heavens: Soldiers, Emperors and Civilians in the Roman Empire. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3523-X.

- Sheppard, Si; Hook, Adam (2010). Farsalo, Cesare contro Pompeo (in Italian). RBA Italia & Osprey Publishing.[ISBN unspecified]

- Wells, Colin Michael (1995). L'impero romano (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-04756-5.