Roy Dowling

Vice Admiral Sir Roy Russell Dowling, KCVO, KBE, CB, DSO (28 May 1901 – 15 April 1969) was a senior commander in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). He served as Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), the RAN's highest-ranking position, from 1955 until 1959, and as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC), forerunner of the role of Australia's Chief of the Defence Force, from 1959 until 1961.

Sir Roy Russell Dowling | |

|---|---|

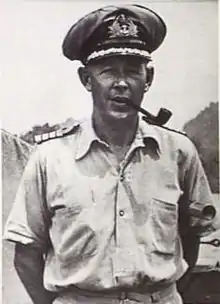

Captain Roy Dowling, 1945 | |

| Born | 28 May 1901 Condong, New South Wales |

| Died | 15 April 1969 (aged 67) Canberra, Australian Capital Territory |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ | Royal Australian Navy |

| Years of service | 1915–61 |

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Unit |

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

| Other work | Australian Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II (1963–69) |

Born in northern New South Wales, Dowling entered the Royal Australian Naval College in 1915. After graduating in 1919 he went to sea aboard several Royal Navy and RAN vessels, and later specialised in gunnery. In 1937, he was given command of the sloop HMAS Swan. Following the outbreak of World War II, he saw action in the Mediterranean theatre as executive officer of the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Naiad, and survived her sinking by a German U-boat in March 1942. Returning to Australia, he served as Director of Plans and later Deputy Chief of Naval Staff before taking command of the light cruiser HMAS Hobart in November 1944. His achievements in the South West Pacific earned him the Distinguished Service Order.

Dowling took command of the RAN's first aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney, in 1948. He became Chief of Naval Personnel in 1950, and Flag Officer Commanding HM Australian Fleet in 1953. Soon after taking up the position of CNS in February 1955, he was promoted to vice admiral and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath. As CNS he had to deal with shortages of money, manpower and equipment, and with the increasing role of the United States in Australia's defence planning, at the expense of traditional ties with Britain. Knighted in 1957, Dowling was Chairman of COSC from March 1959 until May 1961, when he retired from the military. In 1963 he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order and became Australian Secretary to Queen Elizabeth II, serving until his death in 1969.

Pre-war career

Roy Russell Dowling was born on 28 May 1901 in Condong, a township on the Tweed River in northern New South Wales. His parents were sugar cane inspector Russell Dowling and his wife Lily. The youth entered the Royal Australian Naval College (RANC) at Jervis Bay, Federal Capital Territory, in 1915. An underachiever academically, he excelled at sports, and became chief cadet captain before graduating in 1918 with the King's Medal, awarded for "gentlemanly bearing, character, good influence among his fellows and officer-like qualities".[1][2] The following year he was posted to Britain as a midshipman, undergoing training with the Royal Navy and seeing service on HMS Ramillies and HMS Venturous.[3] He was promoted to sub-lieutenant on 15 April 1921. By January 1923 he was back in Australia, serving aboard the cruiser HMAS Adelaide. He was promoted to lieutenant on 15 March.[4] In April 1924, Adelaide joined the Royal Navy's Special Service Squadron on its worldwide cruise, taking in New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Panama, and the West Indies, before docking in September at Portsmouth, England. There Dowling left the ship for his next appointment, training as a gunnery officer and serving in that capacity at HMS Excellent.[3][5]

After returning to Australia in December 1926, Dowling spent eighteen months on HMAS Platypus and HMAS Anzac, continuing to specialise in gunnery. In July 1928, he began instructing at the gunnery school in Flinders Naval Depot on Western Port Bay, Victoria. He married Jessie Blanch in Melbourne on 8 May 1930; they had two sons and three daughters.[1][6] Jessie accompanied him on his next posting to Britain commencing in January 1931. Dowling was promoted to lieutenant commander on 15 March, and was appointed gunnery officer on the light cruiser HMS Colombo in May. He returned to Australia in January 1933, and was appointed squadron gunnery officer aboard the heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra that April.[1][4] The ship operated mainly within Australian waters over the next two years.[7] In July 1935, Dowling took charge of the gunnery school at Flinders Naval Depot. He was promoted to commander on 31 December 1936.[1][4] The following month, he assumed command of the newly commissioned Grimsby-class sloop HMAS Swan, carrying out duties in the South West Pacific.[8] Completing his tenure on Swan in January 1939, he was briefly assigned to the Navy Office, Melbourne, before returning to Britain in March for duty at HMS Pembroke, awaiting posting aboard the yet-to-be-commissioned anti-aircraft cruiser, HMS Naiad.[4]

World War II

Dowling became executive officer on HMS Naiad when the ship was commissioned in 1940. Following service with the British Home Fleet, the cruiser transferred to the Mediterranean Station in May 1941, where she took part in the Battle of Crete.[1][6] She was involved in action against German torpedo boats on the night of 20/21 May. On 22 May, after engaging a German destroyer with HMAS Perth, Naiad was severely damaged by air attack.[9] Following repairs, she became flagship of the 15th Cruiser Squadron and conducted shore bombardments in support of Allied troops during the Syrian campaign in June and July.[10] She also escorted convoys resupplying Malta. In December, Naiad participated in the First Battle of Sirte against Italian naval forces. On 11 March 1942, she was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the Egyptian coast, and sank in just over twenty minutes.[1] Dowling remained in the water for an hour and a half before being rescued by a destroyer.[11]

Having survived Naiad's sinking, Dowling returned to Australia and was appointed Director of Plans at the Navy Office in July 1942.[1] In September the following year he was made Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff (DCNS) and raised to acting captain;[2][6] his rank became substantive on 30 June 1944.[4] As DCNS, he was involved in planning the post-war Navy's composition, which for the first time was to include aircraft carriers.[1] He defined the functions of maritime power in October 1943 as:[12]

(i) Maintenance of our lines of sea communications,

(ii) Destruction of the enemy's lines of sea communications,

(iii) Attack on the enemy's strategic positions in combined operations with Army and Air Force,

(iv) Defence of our bases.

In November 1944, Dowling was given command of the light cruiser HMAS Hobart, which had been undergoing repair and refit in Sydney since being torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in the Solomons on 20 July 1943.[3][13] Dowling took her on her shakedown cruise to Melbourne on 30 December, before embarking for the South West Pacific Area in February 1945. The following month, Hobart supported the US forces that recaptured Cebu during the liberation of the Philippines.[14][15] She bombarded Tarakan Island prior to the Allied invasion on 1 May and, later that month, covered the Australian 6th Division's operations at Wewak.[16][17] The cruiser supported the Allied landings on Brunei in June, and on Balikpapan in July.[18][19] For his "outstanding courage, skill and initiative" during these operations, Dowling was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), gazetted on 6 November 1945.[2][20]

Post-war career

Dowling joined the Australian contingent at the surrender of Japan in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. Following the cessation of hostilities, Hobart became flagship of HM Australian Squadron, and Dowling flag captain and chief of staff to Commodore John Collins, the squadron commander.[1][21] The war had taken a toll on Dowling's health, and he required leave before commencing his next appointment in May 1946 as Director of Ordnance, Torpedoes and Mines at the Navy Office.[1][2] Rear Admiral James Goldrick, in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, observed that Dowling "was thrust into the highest positions of the RAN largely as a result of the heavy casualties of World War II". When John Armstrong—the only similarly qualified and more senior Navy captain—was pronounced unfit for seagoing duty, Dowling was given the chance to command Australia's first aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney, commissioned in England on 16 December 1948. In April the following year, two months after the ship's belated acceptance into service due to teething troubles, Dowling embarked Sydney for Australia with two squadrons of fighters aboard.[1][22]

In June 1950, Dowling was promoted to commodore and appointed Second Naval Member and Chief of Naval Personnel, serving in this capacity until the end of 1952. His term coincided with the outbreak of the Korean War, and resultant increased demands on manpower.[1][3] Dowling was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1953 New Year Honours, before travelling to London to attend the Imperial Defence College.[3][23] Raised to rear admiral in July 1953, he returned home to take up the post of Flag Officer Commanding HM Australian Fleet that December, serving through the following year. He had to preside over cutbacks to operations brought on by government stringency after the Korean War.[1][3]

On 24 February 1955, Dowling succeeded Vice Admiral Sir John Collins as First Naval Member, Australian Commonwealth Naval Board, and Chief of Naval Staff (CNS).[24] He was promoted to vice admiral on 7 June, and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in the Queen's Birthday Honours two days later.[25][26] On 15 June, he joined fellow chiefs of staff Lieutenant General Henry Wells and Air Marshal John McCauley, Prime Minister Robert Menzies, and senior government members in approving a draft directive for the role of the Far East Strategic Reserve (FESR); this made Commonwealth forces available for the fight against communist insurgents in Malaya, as well as for the security of Malaya and Singapore against external aggression.[27] The Navy's contribution to the FESR was to be at least two destroyers or frigates on an ongoing basis, as well as a yearly visit by an aircraft carrier. The destroyers HMAS Arunta and HMAS Warramunga, already in the region on an exercise, were immediately committed, and Dowling flew to Singapore to personally announce the plan and the reasons for it to the ships' crews.[28]

Dowling was an early advocate for the establishment of an Australian submarine fleet; in 1963, after several false starts, the first of six Oberon-class submarines was ordered.[1][29] As part of a general Western trend that viewed with alarm the increasing capability of the Soviet Navy's surface fleet, Dowling also worked to improve the offensive power of the Fleet Air Arm. In March 1956, he went so far as proposing purchase of nuclear weaponry for the RAN's De Havilland Sea Venoms. During much of Dowling's remaining time as CNS, faced with the obsolescence of HMAS Sydney and in accordance with its two-carrier policy, the Navy tried unsuccessfully to acquire a new and larger aircraft carrier to augment HMAS Melbourne.[30] Believing in the maintenance of traditionally close ties between the RAN and the Royal Navy, he worked to coordinate his policies as CNS with those of Britain's First Sea Lord, Earl Mountbatten.[1][3] Taking into account the provisions of the ANZUS treaty and the absence of suitable supplies from Britain, the RAN began to turn reluctantly towards the United States in terms of strategy and equipment,[3] as Dowling explained to Mountbatten:

We now find ourselves at the crossroads because we very much doubt whether the United Kingdom can provide us with what we want in the future. We have no wish to become Americans but there is a strong belief in this country that the sensible course of action for Australians is to acquire war equipment from the United States now. Our very telling reason is of course that, certainly in a global war, our salvation in the Pacific will depend chiefly on the aid of that country. For that we are not less loyal members of the Empire.[31]

Other issues facing the RAN during Dowling's term as CNS were its relegation—since the beginning of the 1950s—to third place behind the other armed forces in terms of Federal budget allocations, its replacement by the RAAF as the country's first line of defence, and a shortage of manpower. Dowling himself considered "separation from families, lack of houses, over employment, high wages and overtime payment in civvie street" as the causes for the Navy's inability to attract and retain personnel; the Allison Report in 1958 led to improvements to service conditions, which helped reduce wastage.[32] The RANC had moved to Flinders Naval Depot in 1930, and Dowling was pleased to be able to oversee its return to Jervis Bay in 1958, the year before he relocated the office of the CNS to Canberra.[1][33]

Dowling was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in the 1957 New Year Honours,[34] and completed his term as CNS on 23 February 1959.[24] On 23 March he took over from Sir Henry Wells as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC), a role foreshadowing that of the Chief of the Defence Force.[35][36] He was succeeded as CNS by Vice Admiral Henry Burrell.[24] Happily surprised by his appointment as Chairman of COSC, Dowling hoped to transform the position such that it would exercise command authority over the service chiefs, but in this he was to be disappointed. The position's rank remained the same as the heads of the Army, Navy and Air Force, and was only responsible for putting their views on military matters to the Minister for Defence.[1][37] Other setbacks during his tenure included the Defence Department's decision—rescinded after his term—to disband the Fleet Air Arm, and the Federal government's failure to back him when he announced at a SEATO press conference in March 1961 that Australia was prepared to intervene militarily in the second Laotian crisis if it became necessary.[1][3] In September 1959, during the first Laotian crisis, the Australian government had authorised Dowling to commit "an infantry battalion, a squadron of RAAF fighters, air transport, and two RAN destroyers" to support US and SEATO forces, but no intervention took place.[38]

Later life

Dowling retired from the military on 27 May 1961 and was succeeded as Chairman of COSC by Air Marshal Sir Frederick Scherger.[35][39] Though keen to secure a diplomatic appointment, nothing was offered to him and, as a practising Anglican, he instead busied himself with church affairs in Canberra. In July 1962, the government gave him responsibility for organising Queen Elizabeth II's upcoming royal tour.[1] In this role he was required to liaise with the state governments to plan the Queen's itinerary, and to become a member of the royal household for the duration of the tour, the first time an Australian tour planner had been given such close access to a visiting monarch.[40] He was rewarded with appointment as a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) as of 27 March 1963, and became Australian Secretary to the Queen on 1 November the same year.[41][42] Dowling was also the Australian Red Cross Society's Canberra chairman from 1962 to 1967; at the time he took over the chairmanship, Lady Dowling was acting president of the organisation, in the absence of Lady William Oliver.[6][11] Roy Dowling died of a heart attack on 15 April 1969 in Canberra Hospital. He was given a naval funeral at St John's Church, and cremated. His wife and five children survived him.[1][43]

Notes

- "Dowling, Sir Roy Russell (1901–1969)". Dowling, Sir Roy Russell. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Eldridge, A History of the Royal Australian Naval College, pp. 79–80

- Dennis et al., Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, p. 188

- "Personal Record – Dowling, Roy R." National Archives of Australia. p. 2. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "HMAS Adelaide (I)". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Legge, Who's Who in Australia 1968, p. 261

- "HMAS Canberra (I)". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "HMAS Swan (II)". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942, pp. 344–346

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942, pp. 379–382

- "Admiral will take orders from wife". The Age. Melbourne. 4 July 1962. p. 4. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Stevens, The Royal Australian Navy, p. 127

- "HMAS Hobart (I)". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, p. 292

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, pp. 600–603

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, pp. 619–623

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, pp. 629–631

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, pp. 639–642

- Gill, Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945, pp. 649–652

- "No. 37338". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 November 1945. p. 5399.

- Commonwealth of Australia (Navy Office). "The Navy List (October 1945)" (PDF). Melbourne. pp. 8, 12. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "HMAS Sydney (III)". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "No. 39734". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1953. p. 39.

- Stevens, The Royal Australian Navy, pp. 310–312

- Commonwealth of Australia (Navy Office). "The Navy List (July 1955)" (PDF). Melbourne. p. 20. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "No. 40498". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 June 1955. p. 3297.

- Edwards, Crises and Commitments, pp. 174–175

- Pfennigwerth, Tiger Territory, pp. 56–58, 75

- Dennis et al., Oxford Companion to Australian Military History, p. 399

- Stevens, The Royal Australian Navy, pp. 186–187

- Frame, No Pleasure Cruise, pp. 219–220

- Stevens, The Royal Australian Navy, pp. 189, 194

- "HMAS Creswell". Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "No. 40961". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1957. p. 42.

- "Chief of the Defence Force". Department of Defence. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "Australian Naval History on 23 March 1959". Naval Historical Society of Australia. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, p. 43

- Edwards, Crises and Commitments, pp. 214–215

- "Dowling, Roy Russell". World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "Admiral to plan 1963 tour by Queen". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 6 July 1962. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- "No. 42969". The London Gazette. 16 April 1963. pp. 3327–3328.

- "No. 43148". The London Gazette. 1 November 1963. p. 8949.

- "Admiral torpedoed in Battle of Crete". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 16 April 1969. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

References

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (2008) [1995]. The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Edwards, Peter; Pemberton, Gregory (1992). Crises and Commitments: The Politics and Diplomacy of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1965. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin in association with the Australian War Memorial. ISBN 1-86373-184-9.

- Eldridge, Frank Burgess (1949). A History of the Royal Australian Naval College. Melbourne: Georgian House. OCLC 14472805.

- Frame, Tom (2004). No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-233-4.

- Gill, George Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Vol. I. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 848228.

- Gill, George Hermon (1968). Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Vol. II. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 65475.

- Horner, David (2001). Making the Australian Defence Force. Australian Centenary History of Defence. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554117-0.

- Legge, J. S., ed. (1968). Who's Who in Australia 1968. Melbourne: The Herald and Weekly Times. OCLC 4171414.

- Pfennigwerth, Ian (2008). Tiger Territory: The Untold Story of the Royal Australian Navy in Southeast Asia from 1948 to 1971. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Rosenberg. ISBN 978-1-877058-65-3.

- Stevens, David, ed. (2001). The Royal Australian Navy: A History. Australian Centenary History of Defence. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554116-2.