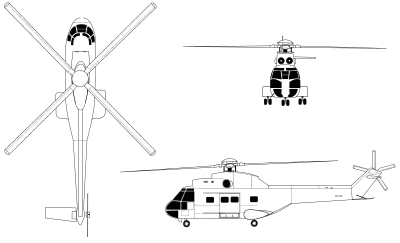

Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma

The Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma is a four-bladed, twin-engined medium transport/utility helicopter that was designed and originally produced by the French aerospace manufacturer Sud Aviation. It is capable of carrying up to 20 passengers as well as a variety of cargoes, either internally or externally; numerous armaments have also been outfitted to some helicopters.

| SA 330 Puma | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A French Army Puma performing over RIAT, 2010 | |

| Role | Utility helicopter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Sud Aviation Aérospatiale |

| First flight | 15 April 1965 |

| Introduction | 1968 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | French Army Royal Air Force Romanian Air Force Pakistan Army |

| Produced | 1968–1987 |

| Number built | 697 |

| Variants | IAR 330 Atlas Oryx |

| Developed into | Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma Eurocopter AS532 Cougar Denel Rooivalk |

The Puma was originally developed as an all-new design during the mid-1960s in response to a French Army requirement for a medium-sized all-weather helicopter. On 15 April 1965, the first prototype Puma made its maiden flight; the first production helicopter flew during September 1968. Deliveries to the French Army commenced in early 1969; the type quickly proved itself to be a commercial success. Production of the Puma continued into the 1980s under Sud Aviation's successor company Aérospatiale. It was also license-produced in Romania as the IAR 330; two unlicensed derivatives, the Denel Rooivalk attack helicopter and Atlas Oryx utility helicopter, were built in South Africa. Several advanced derivatives have been developed, such as the AS332 Super Puma and AS532 Cougar, and have been manufactured by Eurocopter and its successor company Airbus Helicopters since the early 1990s. These descendants of the Puma remain in production in the 21st century.

The Puma has seen combat in a range of theatres by a number of different operators; significant operations include the Gulf War, the South African Border War, the Portuguese Colonial War, the Yugoslav Wars, the Lebanese Civil War, the Iraq War, and the Falklands War. Numerous operators have chosen to modernise their fleets, often adding more capabilities and new features, such as glass cockpits, Global Positioning System (GPS) navigation, and various self-defense measures. The type also saw popular use in the civilian field and has been operated by a number of civil operators. One of the largest civil operators of the Puma was Bristow Helicopters, which regularly used it for off shore operations over the North Sea.

Development

The SA 330 Puma was originally developed by Sud Aviation to meet a requirement of the French Army for a medium-sized all-weather helicopter capable of carrying up to 20 soldiers as well as various cargo-carrying duties. The choice was made to develop a completely new design for the helicopter, work began in 1963 with backing from the French government.[1] The first of two Puma prototypes flew on 15 April 1965; six further pre-production models were also built, the last of which flew on 30 July 1968. The first production SA 330 Puma flew in September 1968, with deliveries to the French Army starting in early 1969.[2]

In 1967, the Puma was selected by the Royal Air Force (RAF), who were impressed by the Puma's performance. It was given the designation Puma HC Mk 1. A significant joint manufacturing agreement was signed between Aerospatiale and Westland Helicopters of the UK. The close collaboration between the French and British firms would lead to purchases of Aérospatiale Gazelle by the UK and the Westland Lynx by France. Under this agreement, Westland manufactured a range of components and performed the assembly of Pumas ordered by the RAF.[3][4][5]

The SA 330 was a success on the export market, numerous countries purchased military variants of the Puma to serve in their armed forces; the type was also popularly received in the civil market, finding common usage by operators for transport duties to off-shore oil platforms.[6] Throughout most of the 1970s, the SA 330 Puma was the best selling transport helicopter being produced in Europe.[7] By July 1978, over 50 Pumas had already been delivered to civil customers, and the worldwide fleet had accumulated in excess of 500,000 operational hours.[8]

Romania entered into an arrangement with Aerospatiale to produce the Puma under license as the IAR 330, manufacturing at least 163 of the type for the Romanian armed forces, civil operators, and several export customers of their own.[9] Indonesia also undertook domestic manufacturing of the SA 330.[10][11] South Africa, a keen user of the type, performed their own major modification and production program conducted by the government-owned Atlas Aircraft Corporation to upgrade their own Pumas, the resulting aircraft was named Oryx. In the 1990s, Denel would also develop an attack helicopter for the South African Air Force based on the Puma, known as the Denel Rooivalk.[9]

In 1974, Aerospatiale began development of improved Puma variants, aiming to produce a successor to the type; these efforts would cumulate in the AS332 Super Puma. The first prototype AS332 Super Puma took flight on 13 September 1978, featuring more powerful engines and a more aerodynamically-efficient extended fuselage; by 1980, production of the AS332 Super Puma had overtaken that of the originating SA 330 Puma.[12] Production of the SA 330 Puma by Aérospatiale ceased in 1987,[13] by which time a total of 697 had been sold;[14] production in Romania would continue into the 21st Century.[12]

Design

The SA 330 Puma is a twin-engine helicopter intended for personnel transport and logistic support duties. As a troop carrier, up to 16 soldiers can be seated on foldable seats; in a casualty evacuation configuration, the cabin can hold six litters and four additional personnel; the Puma can also perform cargo transport duties, using alternatively an external sling or the internal cabin, with a maximum weight of 2500 kg. Civilian Pumas feature a variety of passenger cabin layouts, including those intended for VIP services. In a search and rescue capacity, a hoist is commonly installed, often mounted on the starboard fuselage.[15]

A pair of roof-mounted Turbomeca Turmo turboshaft engines power the Puma's four-blade main rotor. The helicopter's rotors are driven at a speed of roughly 265 rpm via a five reduction stage transmission. The design of the transmission featured several unique and uncommon innovations for the time, such as single-part manufacturing of the rotor shaft and the anti-vibration measures integrated into the main gearbox and main rotor blades.[16] The Puma also featured an automatic blade inspection system, which guarded against and alerted crews to fatigue cracking in the rotor blades. There are two hydraulic systems on board, these operate entirely independent of one another, one system powers only the aircraft's flight controls while the other serves the autopilot, undercarriage, rotor brake, and the flight controls.[17]

In flight, the Puma was designed to be capable of high speeds, exhibit great maneuverability, and have good hot-and-high performance; the engines have an intentionally high level of reserve power to enable a Puma to effectively fly at maximum weight with only one functioning engine and proceed with its mission if circumstances require.[18] The cockpit has conventional dual controls for a pilot and copilot, a third seat is provided in the cockpit for a reserve crew member or commander. The Puma features a SFIM-Newmark Type 127 electro-hydraulic autopilot; the autopilot is capable of roll and pitch stabilization, the load hook operator can also enter corrective adjustments of the helicopter's position from his station through the autopilot.[19]

The Puma is readily air-transportable by tactical airlift aircraft such as the Transall C-160 and the Lockheed C-130 Hercules; the main rotor, landing gear, and tailboom are all detachable to lower space requirements. Ease of maintenance was one of the objectives pursued in the Puma's design; many of the components and systems that would require routine inspection were positioned to be visible from ground level, use of life-limited components was minimised, and key areas of the mechanical systems were designed to be readily accessed.[15] The Puma is also capable of operating at nighttime, in inhospitable flying conditions, or in a wide range of climates from Arctic to desert environments.[20]

Although not included during the original production run, numerous operators of Pumas have installed additional features and modern equipment over the aircraft's service life. The RAF have equipped their Puma fleet with Global Positioning System (GPS) navigation equipment, along with an assortment of self-defense measures including infrared jammers and automatic flares/chaff dispensers, and night vision goggles for night-time flights.[20] The French Army Light Aviation have modernised their Pumas to meet International Civil Aviation Organization standards, this involved additional digital systems to the aircraft, this has included new mission command and control systems, such as the Sitalat data link.[21] Third party companies such as South Africa's Thunder City have provided life extension and modernisation programmes for the Puma, some operators have chosen to refurbish their fleets with glass cockpits.[22]

Operational history

Argentina

During the Falklands War/Guerra de Malvinas in 1982, five SA 330 Pumas of the Argentine Army and one of the Argentine Coast Guard were deployed to the theatre; these could either operate from the decks of Navy vessels as well as performing missions across the breadth of the islands; all were lost in the ensuing conflict.[23] On 3 April, while landing Argentine troops as part of the capture of South Georgia, a Puma was badly damaged by small arms fire from British ground forces and crashed into terrain shortly after.[24] On 9 May, a single Puma was destroyed by a Sea Dart anti-aircraft missile launched from HMS Coventry.[25] On 23 May, a pair of Royal Navy Sea Harriers intercepted three Argentine Pumas in the middle of a supply mission to Port Howard; during the subsequent engagement one Puma was destroyed by colliding with the terrain and a second was disabled and subsequently destroyed by cannon fire from the Sea Harriers, the third Puma escaped.[26] On 30 May, a Puma was lost in the vicinity of Mount Kent under unknown circumstances, possibly due to friendly fire.[27] An article in the Argentine newssite MercoPress states however that on 30 May, at about 11.00 a.m., an Aerospatiale SA-330 Puma helicopter was brought down by a Stinger missile, fired by the SAS, in the vicinity of Mount Kent. Six National Gendarmerie Special Forces were killed and eight more wounded.[28]

France

In September 1979, four Pumas were employed during Operation Barracuda to transport a French assault team directly upon the government headquarters of the Central African Empire; after which confiscated valuables and assorted diplomatic and political records were quickly extracted to the nearby French embassy by continuous air lifts by the Pumas.[29]

One distinctive use of the Puma in French service was as a VIP transport for carrying the President of France both at home and during overseas diplomatic engagements; these duties were transferred to the larger AS332 Super Puma as that became available in sufficient numbers.[30][31]

During the 1991 First Gulf War, France chose to dispatch several Pumas in support of coalition forces engaged in a conflict with Saddam Hussein's Iraq. Those Pumas that had been assigned to the role of performing combat search-and-rescue duties were quickly retrofitted with GPS receivers to enhance their navigational capabilities.[32]

As part of France's contribution to the 1990s NATO-led intervention in the Yugoslav Wars, a number of French Pumas operated in the region alongside other Puma operators such as Britain and the United Arab Emirates; one frequent mission for the type was the vital provision of humanitarian aid missions to refugees escaping ongoing ethnic genocide.[33] In April 1994, a French Puma performed a nighttime extraction of a British SAS squad and a downed Sea Harrier pilot from deep inside hostile Bosnian territory, the aircraft came under small arms fire while retreating from the area.[34][35] On 18 June 1999, a single coordinated aerial insertion of two companies of French paratroopers was performed by 20 Pumas, helping to spearhead the rapid securing of Kosovska Mitrovica by NATO ground forces.[36]

As of 2010, both the French Army and French Navy have opted to procure separate variants of the NHIndustries NH90 to ultimately replace the Puma in French military service.[37]

About 20 SA 330 Pumas remain in French Air and Space Force service as of 2016. Two Pumas of Escadron d'Hélicoptères 1/67 'Pyrénées (EH 1/60) were deployed to Chad and Niger from June 2014 as part of Operation Barkhane to disrupt Islamist insurgency in the Sahel region. Initially operation from N'Djamena in Chad, the detachment later moved forwards to Dirkou and Madama in Niger, supporting ground troops and interdicting supply routes for the insurgents. The detachment returned to France in September 2015, being relieved by French Army helicopters.[38]

Lebanon

In 1980–84, the Lebanese Air Force received from France ten SA 330C Pumas to equip its newly raised 9th transport squadron at Beirut Air Base, where it was initially based. In 1983, the squadron was relocated north of the Lebanese capital, with the machines being dispersed in small improvised helipads around Jounieh and Adma for security reasons. On 23 August 1984 a Puma helicopter carrying the Lebanese Armed Forces' Chief-of-staff and commander of the Seventh Brigade, General Nadim al-Hakim and eight other senior military officers crashed in thick fog near Beirut, all passengers and crewmen being killed.[39] On 1 June 1987, the Lebanese Prime-Minister Rachid Karami was assassinated aboard a Puma helicopter en route to Beirut, when a bomb exploded in an attaché case on his lap. Injured in the explosion were Interior Minister Abdullah Rassi and three of the other twelve aides and crewmen on the helicopter, which was severely damaged.[40][41][42] On 17 January 1988, another Puma helicopter crashed in the Mediterranean off the Bouar coast, killing both the pilot Captain Georges Sadaka and the co-pilot Jean Azzi, though their bodies were never found. During the final phase of the Lebanese Civil War, the Puma fleet – now reduced to seven or six helicopters on flying condition[43] – was used in liaison flights with neighboring Cyprus on behalf of General Michel Aoun's interim military government, although fuel shortages and maintenance problems forced their crews to ground them for most of the time until the end of the war on October 1990.[44]

After the War, the Lebanese Air Force Command made consistent efforts to rebuild its transport helicopter squadron with the help of the United Arab Emirates and seven IAR 330 SM helicopters formerly in service with the United Arab Emirates Air Force were delivered in 2010.[45]

In 2013, the Lebanese Air Force converted an IAR 330 SM into a helicopter gunship by mounting on hardened side-swivel mounts a single ADEN Mk 4/5 30mm revolver cannon on a modified pod and a pair of SNEB 68mm rocket launchers taken from decommissioned Hawker Hunter FGA.70 and FGA.70A fighter jets. Re-designated SA 330SM, the new Puma gunship version underwent trials on October 10 that same year during aerial maneuvers held in Hamat Air Base.[46] Although the trials were successful, the SA 300SM was not accepted for active service, with the Lebanese Air Force Command settling instead on an armed version of the Eurocopter AS532 Cougar, of which seven helicopters were scheduled to be received over the next three years.[47]

Morocco

In 1974, Morocco made an agreement with France for the purchase of 40 Puma helicopters for their armed forces.[48] During the 1970s and 1980s, Moroccan Pumas saw combat service against Polisario Front separatists and helped exert greater control over the Western Sahara region; use of air power by Moroccan forces was severely curtailed after several aircraft were lost or damaged due to the presence of Soviet-provided 2K12 Kub anti-aircraft missiles in rebel hands in the early 1980s.[49]

In October 2007, as part of a €2 billion deal between Morocco and France, a total of 25 Moroccan Pumas are to undergo extensive modernisation and upgrades.[50]

Pakistan

The Pakistan Army has been using Pumas for transportation of army personnel, food and equipment near Siachen regions. The Siachen Glacier is the highest battleground on earth, claimed by both India and Pakistan, but administered by India. Pakistan maintains permanent military presence near the region at a height of over 6,000 metres, just about 915 metres below the Indian presence.

Portugal

In 1969, Portugal emerged as an early export customer for the Puma, ordering 12 of the helicopters for the Portuguese Air Force; Portugal would also be the first country to employ the Pumas in combat operations during the Portuguese Colonial War; the type was used operationally to complement the smaller Alouette III helicopter fleet during the Angola and Mozambican wars of independence, the type had the advantages of greater autonomy and transport capacity over other operated helicopters.[51]

During the 1980s, Portugal engaged in an illicit arrangement with South Africa in order to circumvent a United Nations embargo being enforced upon South Africa under which France had refused to provide upgrades and spares for South Africa's own Puma fleet. In the secretive deal, Portugal ordered more powerful engines and new avionics with the public intention of employing them on its own Pumas, however many of the components were diverted via a Zaire-based front company to South African defense firm Armscorp, where they were used to overhaul, upgrade and rebuild the existing Pumas, ultimately resulting in the Atlas Oryx; the Portuguese Pumas also received significant upgrades which were paid for under the terms of the agreement.[52]

In 2006, the Portuguese Air Force began receiving deliveries of the AgustaWestland AW101 Merlin, a larger and more capable helicopter, replacing the aging Puma fleet.[53]

Since 2007, Portugal has tried unsuccessfully to sell 8 Pumas. Again in May 2015 it is trying to sell them again.[54]

South Africa

From 1972 onwards, Pumas operated by the SAAF were deployed on extended operations in South West Africa and Angola during the Border War. The Puma was involved in normal trooping; rapid deployment during "follow up" operations; acting as radio relays; evacuation of casualties; rescuing downed aircrew; insertion of Special Forces; and large scale cross border operations such as Savannah, Uric, Protea, Super, and Modular.

The majority of South African Puma purchases, including spare parts, were made in advance of an anticipated United Nations embargo that was applied in 1977.[55] South Africa subsequently upgraded many of its Pumas, eventually arriving at the derived indigenous Atlas Oryx; external assistance and components were obtained via secretive transactions involving Portugal during the arms embargo era.[52][56]

In December 1979, South Africa's government acknowledged the presence of its military forces operating in Rhodesia; Pumas were routinely used in support of the South African Army's ground forces.[57] In June 1980, 20 Pumas accompanied a force of 8,000 troops during a South African invasion of Angola in pursuit of nationalist SWAPO fighters.[58] In 1982, the government confirmed that 15 servicemen had been killed when a South African Puma was downed by SWAPO forces, it was one of the worst losses suffered in a single incident in the conflict.[59]

During the 1990s, clandestine efforts to purchase surplus SAAF Pumas were made by then-President Pascal Lissouba of the Republic of Congo, most likely intended for use in the Congolese Civil War.[60] When the cruise ship MTS Oceanos sank off the Wild Coast of South Africa in 1991, as many as 13 Pumas played crucial roles in the rescue efforts, winching 225 survivors to safety during bad weather conditions.[61]

United Kingdom

The first two Pumas for the Royal Air Force were delivered on 29 January 1971,[62][63] with the first operational squadron (33 Squadron) forming at RAF Odiham on 14 June 1971.[64] The RAF would order a total of 48 Puma HC Mk 1 for transport duties; during the Falklands War, an additional SA 330J formerly operated by Argentine Naval Prefecture was captured by British forces and shipped back to Britain and used as a RAF static training aid for several years. This SA 330J was later refurbished by Westland using parts from damaged RAF Puma XW215 and put into RAF service after a lengthy rebuild as ZE449.[65] The Puma became a common vehicle for British special forces, such as the SAS, and has been described as being "good for covert tasks".[66]

Between the early 1970s and the 1990s, RAF Pumas were based at RAF Odiham (33 Squadron and 240 OCU), RAF Gutersloh (230 Squadron) and No. 1563 Flight RAF at RAF Belize. During The Troubles it was also common for a detachment to be based at RAF Aldergrove in Northern Ireland. In 1994, 230 Squadron relocated to RAF Aldergrove to provide a permanent presence to augment the Westland Wessex of 72 Squadron. In 2009, 230 Squadron relocated to RAF Benson together with 33 Squadron from RAF Odiham.

Royal Air Force Pumas have also seen active service in Venezuela, Iraq, Yugoslavia, and Zaire.[67] Britain has frequently dispatched Pumas on disaster relief and humanitarian missions, such as during the 2000 Mozambique flood and the 1988 Jamaican flash flood;[68] and to conduct peacekeeping operations in regions such as Zimbabwe and the Persian Gulf.[67]

During the climax of the First Gulf War, a joint force of Pumas from 230 and 33 Squadrons proved decisive in rapidly mobilizing and deploying troops to prevent Iraqi troops from sabotaging the Rumaila oil field.[66] From the beginning of the Iraq War, between 2003 and 2009, RAF Pumas would be used to provide troop mobility across the theatre.[69] On 15 April 2007, two RAF Pumas collided during a special forces mission close to Baghdad, Iraq.[70] In November 2007, a Puma crashed during an anti-insurgent operation in Iraq; an inquest found the cause to be pilot error primarily, however the Ministry of Defence (MoD) was criticised for failing to equip RAF Pumas with night vision goggles and inadequate maintenance checks compromising safety, these shortcomings were addressed following the incident.[71]

In order to extend the type's service, six ex-South African SA 330L were purchased by Britain in 2002.[72] A programme to produce an extensive upgrade of the RAF's Pumas saw the first Puma HC Mk2 enter service in late 2012 and was completed by early 2014,[73] enabling the Puma fleet to remain in operational service until 2025. In 2008, it was envisaged that 30 aircraft would be upgraded,[74] this was subsequently cut to 22,[75] and was later revised upwards for a total of 24 HC Mk2 Pumas to be produced.[76] Upgrades include the integration of two Turbomeca Makila engines, new gearboxes and tail rotors, new engine controls, digital autopilot, a flight management system, an improved defensive aids suite, as well as ballistic protection for helicopter crew and passengers. The upgraded aircraft can transport double the payload over three times the range than its predecessor, and will be deployed for tactical troop transport, as well as fast moving contingent combat and humanitarian operations.[77]

It is expected that the RAF will replace its Puma fleet in the mid-2020s, with the replacement aircraft being procured through the New Medium Helicopter programme.[78]

Civil

One of the largest and prominent operators of the type was Bristow Helicopters, where the Puma was regularly used for off shore operations over the North Sea.[9][79] during the 1970s, Bristow had sought to begin replacing their Sikorsky S-61 helicopters, the Puma was selected after a highly competitively-priced bid had been made by Aerospatiale; Puma G-BFSV was the first of the type to enter service with Bristow.[80] From 1979 onwards, the Puma formed the mainstay of the Bristow fleet;[81] the type took over the duties of Bristow's retiring Westland Wessex helicopters in 1981.[82] In 1982, Bristow introduced the more powerful Super Puma into service, supplementing their then-total fleet of 11 SA 330J Pumas.[83]

Erickson Inc. has operated four Pumas since 2014. They are used for Vertical replenishment (VERTREP) to the United States Fifth Fleet and United States Seventh Fleet.[84]

Variants

| External video | |

|---|---|

Aérospatiale versions

- SA 330A

- Prototypes, originally called "Alouette IV".[85]

- SA 330B

- Initial production version for the French Army Light Aviation. Powered by 884 kW (1,185 hp) Turbomeca Turmo IIIC4 engines. 132 purchased by France.[86]

- SA 330 Orchidée

- SA 330 modified to carry an Orchidée battlefield surveillance radar system with a rotating underfuselage antenna, for the French Army. One demonstrator was built, flying in 1986. The Orchidée programme was cancelled in 1990, but the prototype rushed back into service in 1991 to serve in the Gulf War, leading to production of a similar system based on the Eurocopter Cougar.[87]

- SA 330C

- Initial export production version. Powered by 1,044 kW (1,400 hp) Turbomeca Turmo IVB engines.[88]

- SA.330E

- Version produced by Westland Helicopters for the RAF under the designation Puma HC Mk. 1.

- SA.330F

- Initial civilian export production version with Turbomeca Turmo IIIC4 turboshaft engines.[89]

- SA.330G

- Upgraded civilian version with 1175 kW (1,575 hp) Turbomeca Turmo IVC engines.[89]

- SA.330H

- Upgraded French Army and export version with Turbomeca Turmo IVC engines and composite main rotor blades. Designated SA 330Ba by the French Air and Space Force. All surviving French Army SA 330Bs converted to this standard.[89]

- SA.330J

- Upgraded civil transport version with composite rotor blades and with higher maximum takeoff weight.[90]

- SA.330L

- Upgraded version for "hot and high" conditions. Military equivalent to civil SA.330J.[90]

- SA.330S

- Upgraded SA 330L (themselves converted from SA 330C) version for the Portuguese Air Force. Powered by Turbomeca Makila engines.[90]

- SA.330SM

- Lebanese converted gunship version by mounting on hardened side-swivel mounts a single ADEN Mk 4/5 30mm revolver cannon on a modified pod and a pair of SNEB 68mm rocket launchers on each side.

- SA.330Z

- Prototype with "fenestron" tail rotor.[91]

- SA.331 Puma Makila

- Engine test-bed for the AS.332 Super Puma series, powered by two Turbomeca Makila engines

Versions by other manufacturers

- Atlas Aircraft Corporation Oryx

- Remanufactured and upgraded SA 330 Puma built for the South African Air Force.

- IPTN NAS 330J

- Version that was assembled by IPTN of Indonesia under the local designation NAS 330J and the Aerospatiale designation of SA 330J. Eleven units were produced.

- IAR 330

- Licence-built version of the SA 330 Puma manufactured by Industria Aeronautică Română of Romania. Designated as the SA 330L by Aerospatiale.

- IAR-330 Puma SOCAT

- 24 modified for antitank warfare.

- IAR-330 Puma Naval

- 3 modified for the Romanian Navy, using the SOCAT avionics.

- Westland Puma HC Mk 1

- SA 330E equivalent assembled by Westland Helicopters for the RAF, first flown on 25 November 1970. Several similarities to the SA 330B employed by the French Armed Forces. The RAF placed an initial order for 40 Pumas in 1967, with a further eight attrition replacement aircraft in 1979.[65]

- Airbus Helicopters Puma HC.Mk 2

- Modified Puma HC Mk1s,[92] total of 24 upgraded with more powerful Turbomeca Makila 1A1 engines, a glass cockpit and new avionics, secure communications and improved self-protection equipment.[73]

Operators

Current operators

.jpg.webp)

- French Air and Space Force[93][94]

- Cayenne – Félix Eboué Airport, French Guiana

- Djibouti–Ambouli International Airport, Djibouti

- La Tontouta International Airport, New Caledonia

- Solenzara Air Base, Haute-Corse, France

- French Army Light Aviation[93]

- Military of Gabon[93][95]

- Léon-Mba International Airport, Libreville

- Escadrille Aérienne Transport

- Léon-Mba International Airport, Libreville

- Indonesian Air Force[93][96]

- Atang Senjaya Airbase, West Java

- Skadron Udara 8

- Atang Senjaya Airbase, West Java

- Kenya Air Force[93][97]

- Moi Air Base, Nairobi City County

- Helicopter Squadron

- Moi Air Base, Nairobi City County

- Lebanese Air Force[93][98]

- Wujah Al Hajar Air Base, Hamat

- 9 Squadron

- Wujah Al Hajar Air Base, Hamat

- Royal Moroccan Air Force[93][99]

- First Air Base, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra

- Escadrons de Manoeuvres Tactiques

- First Air Base, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra

- Pakistan Air Force[93]

- Pakistan Army Aviation Corps[93][100]

- Multan International Airport, Punjab

- 24th Army Aviation Squadron

- Qasim Airbase, Dhamial

- 13th Army Aviation Squadron

- 28th Army Aviation Squadron

- Multan International Airport, Punjab

- Romanian Air Force (See IAR 330)[93][101]

- 71st Air Base, Cluj County

- Escadrila 712

- Escadrila 713

- 90th Airlift Base, Ilfov County

- Escadrila 903

- 95th Air Base, Bacău County

- Escadrila 952

- 71st Air Base, Cluj County

- Romanian Navy (See IAR 330)[93][102]

- Tuzla Aerodrome, Constanța County

- Grupul 256

- Tuzla Aerodrome, Constanța County

- Royal Air Force[93]

- RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus

- No. 84 Squadron (2023–present)[103]

- RAF Benson, Oxfordshire, England

- No. 22 Squadron (OEU) (2020–present)[104]

- No. 33 Squadron (1971–present)

- No. 230 Squadron (1971–present)

- RAF Odiham, Hampshire, England

- No. 28 Squadron (OCU) (2015–present)

- Medicina Lines, Brunei

- No. 1563 Flight (1971–1993; 2004–2009; 2022–present)[105]

- RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus

Former operators

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

- Royal Air Force

- RAF Odiham, Hampshire, England

- No. 27(R) Squadron (OCU) (1993–1998)[122]

- No. 240 Operational Conversion Unit (1971–1993)[123]

- RAF Aldergrove, County Antrim, Northern Ireland

- No. 72 Squadron (1997–2002)[124]

- RAF Odiham, Hampshire, England

Notable accidents and incidents

- 29 March 2022 – Eight UN peacekeepers (six Pakistanis, a Russian and a Serb), part of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo were killed in a crash of a Puma helicopter operated by the Pakistan Army Aviation Corps while on a reconnaissance mission in the troubled eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Cause of the crash is yet to be ascertained.[125][126][127][128]

Specifications (SA 330H Puma)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1976–77[129]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3

- Capacity: 16 passengers

- Length: 18.15 m (59 ft 6½ in)

- Rotor diameter: 15.00 m (49 ft 2½ in)

- Height: 5.14 m (16 ft 10½ in)

- Disc area: 177.0 m² (1,905 ft²)

- Empty weight: 3,536 kg (7,795 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 7,000 kg (15,430 lb)

- Powerplant: 2× Turbomeca Turmo IVC turboshafts, 1,175 kW (1,575 hp) each

Performance

- Never exceed speed: 273 km/h (147 knots, 169 mph)

- Maximum speed: 257 km/h (138 knots, 159 mph)

- Cruise speed: 248 km/h (134 knots, 154 mph) econ cruise

- Range: 580 km (313 nm, 360 mi)

- Service ceiling: 4,800 m (15,750 ft)

- Rate of climb: 7.1 m/s (1,400 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns:

- Coaxial 7.62 mm (0.30 in) machine guns

- Side-firing 20 mm (0.787 in) cannon

- Various others

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

- Atlas Oryx

- Denel Rooivalk

- Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma

- Eurocopter AS532 Cougar

- Eurocopter EC225 Super Puma Mk II+

- Eurocopter EC725 Super Cougar

- IAR 330

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Citations

- McGowen 2005, p. 123.

- Taylor 1976, p. 41.

- Lake 2001, pp. 97–98.

- James 1991, pp. 485–486.

- Frawley 1997, p. 13

- Green 1978, p. 70.

- Leishman 2006, p. 43.

- Lambert, Mark. "Aerospatiale chases civil helicopter sales." Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 8 July 1978. p. 76.

- McGowen 2005, p. 124.

- Waldron, Greg (8 July 2011). "Eurocopter renews Indonesia partnership". FlightGlobal.

- "1965: SA330 Puma." Archived March 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Eurocopter, Retrieved: 7 April 2013.

- McGowen 2005, p. 154.

- Lake 2001, p. 100.

- Taylor 1988, p. 57.

- Neal 1970, pp. 814–815

- Neal 1970, pp. 814–817

- Neal 1970, p. 817.

- Neal 1970, p. 814.

- Neal 1970, p. 815

- "Puma HC1." Archived 2013-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 10 April 2013.

- Lert, Frédéric. "France trials new digital helicopter information systems." Archived 2015-01-20 at the Wayback Machine IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, 30 November 2014.

- Birns, Hilka. "Thunder City launches Puma conversion programme." Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 15 October 2008.

- Smith 2006, pp. 23–24, 38

- Smith 2006, pp. 16–17

- Smith 2006, p. 122

- Smith 2006, pp. 82, 123

- Smith 2006, p. 124

- "Argentine Puma shot down by american "Stinger" missile. — MercoPress". MercoPress. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- Titley 1997, p. 136

- Titley 1997, p. 71

- Ripley 2010, p. 11

- Rip and Hasik 2002, p. 155

- Ripley 2010, pp. 56, 60, 81–82

- Ryan, Mike (2005). The operators (1. publ. ed.). London: Collins. pp. 33–35. ISBN 0-00719-937-6.

- "Downed British Jet's Pilot Rescued in Bosnia". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 17 April 1994. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- Ripley 2010, pp. 77–78

- Fleury, Pascale (17 December 2010). "Eurocopter's first NH90 TTH tactical transport helicopter for France performs its maiden flight". Eurocopter. Archived from the original on 2013-07-29.

- Kraak Air International December 2016, pp. 88–95.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 148.

- Ihsan Hijazi: "Lebanese premier is assassinated in copter blast", The New York Times, 2 June 1987

- "Prime Minister Karami killed". Times Daily. 2 June 1987. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- "Helicopter Bomb Blast Kills Lebanese Premier". Los Angeles Times. AP. 1 June 1987. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "World Air Forces 1983". flightglobal.com. p. 359. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Micheletti and Debay, Victoire a Souk El-Gharb – la 10e Brigade sauve le Liban (1989), p. 18.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.inss.org.il. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "SA/IAR 330 Puma – Military In the Middle East". milinme.wordpress.com. 23 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- "الموقع الرسمي للجيش اللبناني".

- Keucher 1987, p. 65

- Dean 1986, pp. 46–47

- Jarry, Emmanuel (23 October 2007). "Sarkozy starts Morocco trip with rail deal". Independent Online. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Bosgra and Krimpen 1972, pp. 27–32

- Vegar, Jose. "Stiffed Arms Merchant Sues". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 1997, 53(6). pp. 12–13

- Agência LUSA (3 February 2006). ""Velhos" PUMA despedem-se sexta-feira com chegada de oito EH-101". RTP. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- SIC (20 May 2015). "Governo volta a tentar vender 8 helicópteros da Guerra Colonial". SIC. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "South Africa Ready to Handle Global Squeeze." Toledo Blade, 1 November 1977

- "Pik to testify in Oryx-smuggling dispute". Mail & Guardian. 13 March 1998. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Forces in Zimbabwe, South Africa Admits". Milwaukee Journal. 2 December 1979. p. 20.

- "Report: South African Forces take up Position in Angola". St Petersburg Times. 27 June 1980. p. 15.

- Alexander, Douglas (12 August 1982). "15 South Africans killed in Angola Push". The Age. Fairfax Media. p. 9.

- "Offshore records solve mystery of civil war chopper deal". Mail & Guardian. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Wren, Christopher S (5 August 1991). "Over 500 Are Rescued as Greek Cruise Ship Sinks Off South African Coast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "World News" Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, Vol. 99, No. 3230, 4 February 1971, p. 144

- "Wildcat Work-Out" Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, Vol. 99, No. 3240, 15 April 1971, pp. 532–534

- Ashworth 1989, p. 108

- Lake 2001, pp. 102–103

- Ryan 2005, p. 95

- "33 Squadron History." Archived 2013-06-15 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 8 April 2013.

- McGreal, Chris (2 April 2000). "Flood aid 'not enough' – UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Ryan 2005, p. 170

- Judd, Terri (16 April 2007). "Two British soldiers killed in Iraq as helicopters collide". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2015-07-08. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Savill, Richard. "Fuel safety valves on fatal Puma crash helicopter `had not been checked for 30 years’." Archived 2018-01-17 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph, 9 December 2009

- Penney Flight International 26 November – 2 December 2002, p. 74

- "UK MoD receives first upgraded Puma HC2." Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 13 September 2012. Retrieved: 5 January 2013

- "RAF gets funds for more Reaper UAVs, Puma upgrade." Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 5 September 2008. Retrieved: 23 December 2008

- "Upgraded Puma HC2 to enter final flight test phase." Archived 2012-09-20 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal, 11 July 2012. Retrieved: 29 August 2012.

- "Last Puma heads for life extension" (PDF). Ministry of Defence – Defence equipment and support. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "UK MoD receives first upgraded Puma HC Mk2 helicopter". Airforce Technology. 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Defence and Security Industrial Strategy: A strategic approach to the UK's defence and security industrial sectors (CP 410)" (PDF). Gov.uk. Ministry of Defence. 26 March 2021. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-23. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Healey 2003, p. 233

- Healey 2003, pp. 127, 139

- Healey 2003, p. 127

- "Air Crash Firm Scraps 'Risky' Helicopter Fleet". The Herald. Newsquest. 10 November 1981. p. 1.

- Healey 2003, p. 139

- "SA330 Puma in Erickson". Helis.com.

- Colonges, Monique; De Silva, Christian (2019). 1939-2019 Marignane - 80 Years of Pioneering (PDF). Airbus Helicopters. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 Jun 2021.

- Lake 2001, p. 101

- Lake 2001, p. 104

- Lake 2001, p. 102

- Lake 2001, p. 103

- Lake 2001, p. 105

- Lake 2001, p. 106

- "Puma HC2". Royal Air Force. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- "World Air Forces 2021". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "Armée de l'air". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Gabon Army & Gendarmerie". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Indonesia Air Force". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Kenya Air Force". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Lebanese Air Force". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Royal Moroccan Air Force". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Pakistan Army". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Romania Air Force". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Romania Navy". scramble.nl. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Cacoyannis, Xenia Zubova Sofie (4 April 2023). "Start of a new era at RAF Akrotiri as Pumas replace Griffin helicopters in Cyprus". forces.net. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- "22 Squadron Re-Forms At RAF Benson". Royal Air Force. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Despite the best efforts of the weather 1563 Flt has recently achieved Initial Operating Capability in Brunei with a further 2 Puma aircraft undertaking air testing prior to being available for tasking and training". RAF Benson (Facebook). 12 October 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- World's Air Forces 1987, Flight International, 28 November 1987, p. 38, archived from the original on 16 May 2013, retrieved 23 March 2013

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 40". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 42". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World Air Forces 2019". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World's Air Forces 1987". Flight International. 28 November 1987. p. 52. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "World's Air Forces 1987". Flight International. 28 November 1987. p. 65. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "World Air Forces 1983 pg. 352". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World Air Forces 2013" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "World Air Forces". Flight International. 1987. p. 74. Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- "Directory World Air Forces 2004". Flight International. Reed Business Information. 16–22 November 2004. p. 80. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 80". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 81". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 84". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ""World's Air Forces." Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 5–11 December 1990, p. 76

- "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 95". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Barry Wheeler (28 August 1975), World Air Forces 1975, Flight International, p. 291, archived from the original on 16 May 2013, retrieved 23 March 2013

- "No.27 Squadron". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "240 Operational Conversion Unit". Air of Authority - A History of RAF Organisation. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "No.72 Squadron". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Eight killed as UN helicopter crashes in eastern DRC". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- "Six Pakistan Army officers, soldiers martyred in UN copter crash". The Express Tribune. 2022-03-29. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- Siddiqui, Naveed (2022-03-29). "Six Pakistani officers, soldiers martyred in helicopter crash in Congo: ISPR". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- "Eight UN peacekeepers killed in helicopter crash in DRC". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 2022-03-29. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- Taylor 1976, pp. 41–42

Bibliography

- Andrade, John. Militair 1982. London: Aviation Press Limited, 1982. ISBN 0 907898 01 7.

- Ashworth, Chris. Encyclopedia of Modern Royal Air Force Squadrons. Wellingborough, UK: Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989. ISBN 1-85260-013-6.

- Dean, David J. The Air Force role in low-intensity conflict. Air University Press, 1986. ISBN 1-42892-827-8.

- Edgar O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon, 1975–92, Palgrave Macmillan, London 1998. ISBN 0-333-72975-7

- Frawley, Gerard. The International Directory of Civil Aircraft. Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 1997 ISBN 1-875671-26-9

- Green, William. The illustrated encyclopedia of the world's commercial aircraft. Crescent Books, 1978. ISBN 0-51726-287-8.

- Healey, Andrew. Leading from the front: Bristow Helicopters, the first 50 years. Tempus, 2003. ISBN 0-75242-697-4.

- Jackson, Paul A. French Military Aviation. Earl Shilton, Leicestershire, England :Midland County Publications, 1979. ISBN 0 904597 18 0

- James, Derek N. Westland Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-847-X.

- Jefford, C G. RAF Squadrons, first edition 1988, Airlife Publishing, UK, ISBN 1 85310 053 6.

- Keucher, Ernest. R. Military assistance and foreign policy. Air Force Institute of Technology, 1989. ISBN 0-91617-101-9.

- Kraak, Jan. "Desert Puma". Air International, December 2016, Vol. 91, No. 6. pp. 88–95. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Lake, Jon. "Variant File: Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma". International Air Power Review, Volume 2 Autumn/Fall 2001. Norwalk, CT, USA: AIRtime Publishing. ISBN 1-880588-34-X. ISSN 1473-9917. pp. 96–107.

- Leishman, J. Gordon. Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-52185-860-7.

- McGowen, Stanley S. Helicopters: An Illustrated History Of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-468-7.

- Neal, Molly. "SNIAS-Westland SA.330 Puma." Flight International, 14 May 1970. pp. 810–817.

- Micheletti, Éric and Debay, Yves. Victoire a Souk El-Gharb – la 10e Brigade sauve le Liban in Liban – dix jours aux Coeur des combats, RAIDS magazine n.º41, October 1989. ISSN 0769-4814. pp. 18–24.

- Penney, Stuart. "World Air Forces 2002". Flight International, Vol. 162, No. 4859, 26 November – 2 December 2002. pp. 33–78.

- Rip, Michael Russel and James M. Hasik. The Precision Revolution: GPS and the Future of Aerial Warfare. Naval Institute Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55750-973-5.

- Ripley, Tim. Conflict in the Balkans 1991–2000. Osprey Publishing, 2010. ISBN 1-84176-290-3.

- Ryan, Mike. The Operators: Inside the World's Special Forces. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 0-00719-937-6.

- Smith, Gordon. Battle Atlas of the Falklands War 1982. Naval-History.net, 2006. ISBN 1-84753-950-5.

- Ray Sturtivant, RAF Flying Training and Support Units since 1912, Air-Britain (Historians), England, 2007, ISBN 0 85130 365 X

- Taylor, John W. R., ed. Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1976–77. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1976. ISBN 0-354-00538-3.

- Taylor, John W. R., ed. Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1988–89. Coulsdon, Surrey, UK: Jane's Information Group, 1988. ISBN 0-7106-0867-5.

- Titley. Brian. Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa. McGill-Queen's Press, 1997. ISBN 0-77357-046-2.

- Krimpen, Van and C. Bosgra. Portugal and NATO. Angola Comite, 1972.

- Wheeler, Barry. "World Air Forces 1975". Flight International, Vol. 108, No. 3468, 28 August 1975. pp. 290–314.