Mozambican War of Independence

The Mozambican War of Independence (Portuguese: Guerra da Independência de Moçambique, 'War of Independence of Mozambique') was an armed conflict between the guerrilla forces of the Mozambique Liberation Front or FRELIMO (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique) and Portugal. The war officially started on September 25, 1964, and ended with a ceasefire on September 8, 1974, resulting in a negotiated independence in 1975.

| Mozambican War of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Portuguese Colonial War, the Decolonisation of Africa, and the Cold War | |||||||

Samora Machel reviewing FRELIMO troops | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000–20,000[37][38] | 50,000 (May 17, 1970)[39] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Uncertain, heavy | ~10,000 (killed and wounded) | ||||||

| ~50,000 civilians killed | |||||||

Portugal's wars against guerrilla fighters seeking independence in its 400-year-old African territories began in 1961 with Angola. In Mozambique, the conflict erupted in 1964 as a result of unrest and frustration amongst many indigenous Mozambican populations, who perceived foreign rule as exploitation and mistreatment, which served only to further Portuguese economic interests in the region. Many Mozambicans also resented Portugal's policies towards indigenous people, which resulted in discrimination and limited access to Portuguese-style education and skilled employment.

As successful self-determination movements spread throughout Africa after World War II, many Mozambicans became progressively more nationalistic in outlook, and increasingly frustrated by the nation's continued subservience to foreign rule. For the other side, many enculturated indigenous Africans who were fully integrated into the social organization of Portuguese Mozambique, in particular those from urban centres, reacted to claims of independence with a mixture of discomfort and suspicion. The ethnic Portuguese of the territory, which included most of the ruling authorities, responded with increased military presence and fast-paced development projects.

A mass exile of Mozambique's political intelligentsia to neighbouring countries provided havens from which radical Mozambicans could plan actions and foment political unrest in their homeland. The formation of FRELIMO and the support of the Soviet Union, Romania, China, Cuba, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Tanzania, Zambia, Egypt, Algeria, Gaddafi regime in Libya and Brazil through arms and advisers, led to the outbreak of violence that was to last over a decade.

From a military standpoint, the Portuguese regular army held the upper hand during the conflict against FRELIMO guerrilla forces. Nonetheless, Mozambique succeeded in achieving independence on June 25, 1975, after a civil resistance movement known as the Carnation Revolution backed by portions of the military in Portugal overthrew the Salazar regime, thus ending 470 years of Portuguese colonial rule in the East African region. According to historians of the Revolution, the military coup in Portugal was in part fuelled by protests concerning the conduct of Portuguese troops in their treatment of some of the indigenous Mozambican populace.[40][41] The growing communist influence within the group of Portuguese insurgents who led the military coup and the pressure of the international community in relation to the Portuguese Colonial War were the primary causes of the outcome.[42]

Background

Portuguese colonial rule

San hunter and gatherers, ancestors of the Khoisani peoples, were the first known inhabitants of the region that is now Mozambique, followed in the 1st and 4th centuries by Bantu-speaking peoples who migrated there across the Zambezi River. In 1498, Portuguese explorers landed on the Mozambican coastline.[43] Portugal's influence in East Africa grew throughout the 16th century; it established several colonies known collectively as Portuguese East Africa. Slavery and gold became profitable for the Europeans; influence was largely exercised through individual settlers and there was no centralised administration.[44]

By the 19th century, most of Africa fell under European colonial rule. Having lost control of the vast territory of Brazil in South America, the Portuguese began to focus on expanding their African colonies. This brought them into direct conflict with the British.[43] Since David Livingstone had returned to the area in 1858 in an attempt to foster trade routes, British interest in Mozambique had risen, alarming the Portuguese government. During the 19th century, much of Eastern Africa was still being brought under British control, and in order to facilitate this, the British government required several concessions from the Portuguese colony.[45]

As a result, in an attempt to avoid a naval conflict with the superior Royal Navy, Portugal adjusted the borders of its colony and the modern borders of Mozambique were established in May 1881.[43] Control of Mozambique was left to various organisations such as the Mozambique Company, the Zambezi Company and the Niassa Company which were financed by British investors and provided with cheap labour by immigrants from British East Africa to work mines and construct railways.[43]

The Gaza Empire, a collection of indigenous tribes who inhabited the area that now constitutes Mozambique and Zimbabwe, was defeated by the Portuguese in 1895,[45] and the remaining inland tribes were eventually defeated by 1902; in that same year, Portugal established Lourenço Marques as the capital.[46] In 1926, political and economic crisis in Portugal led to the establishment of the Second Republic (later to become the Estado Novo), and a revival of interest in the African colonies. Calls for self determination in Mozambique arose shortly after World War II, in light of the independence granted to many other colonies worldwide in the great wave of decolonisation.[37][44]

Rise of FRELIMO

Portugal designated Mozambique an overseas territory in 1951 in order to show the world that the colony had greater autonomy. It was called the Overseas Province of Mozambique (Província Ultramarina de Moçambique). Nonetheless, Portugal still maintained strong control over its colony. The increasing number of newly independent African nations after World War II,[37] coupled with the ongoing mistreatment of the indigenous population, encouraged the growth of nationalist sentiment within Mozambique.[43]

Mozambique was marked by large disparities between the wealthy Portuguese and the rural indigenous African population. Poorer whites, including illiterate peasants, were given preference in lower-level urban jobs, where a system of job reservation existed.[47] In the rural areas, Portuguese controlled the trading stores with which African peasants interacted.[48] Being largely illiterate and preserving their local traditions and ways of life, skilled employment opportunities and roles in administration and government were rare for these numerous tribal populations, leaving them few or no opportunities in the urban modern life. Many indigenous peoples saw their culture and tradition being overwhelmed by the alien culture of Portugal.[44] A small educated African class did emerge, but faced substantial discrimination.[49]

Vocal political dissidents opposed to Portuguese rule and claiming independence were typically forced into exile. From the mid-1920s onward, unions and left-wing opposition groups were suppressed within both Portugal and its colonies by the authoritarian Estado Novo regime.[49] The Portuguese government forced black Mozambican farmers to grow rice or cotton for export, providing little for the farmers to support themselves. Many other workers—over 250,000 by 1960—were pressured to work on coal and gold mines in neighbouring territories, mainly in South Africa, where they comprised over 30% of black underground miners.[37][43][44][50] By 1950, only 4,353 Mozambicans out of 5,733,000 had been granted the right to vote by the Portuguese colonial government.[44] The rift between Portuguese settlers and Mozambican locals is illustrated in one way by the small number of people with mixed Portuguese and Mozambican heritage (mestiço), numbering only 31,465 in a population of 8–10 million in 1960 according to that year's census.[37]

The Mozambique Liberation Front, or FRELIMO, formally Marxist-Leninist as of 1977 but adherent to such positions since the late 1960s,[51] was formed in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on June 25, 1962, under the leadership of sociologist Eduardo Mondlane. It was created during a conference of political figures who had been forced into exile,[52] by the merging of various existing nationalist groups, including the Mozambican African National Union, National African Union of Independent Mozambique and the National Democratic Union of Mozambique which had been formed two years earlier. It was only in exile that such political movements could develop, due to the strength of Portugal's grip on dissident activity within Mozambique itself.[44]

The United Nations also put pressure on Portugal to move for decolonisation. Portugal threatened to withdraw from NATO, which put a stop to pressure from within the NATO bloc, and nationalist groups in Mozambique were forced to turn to Soviet bloc for aid.[37]

International consciousness and support

Leaders of the Mozambican independence movement were educated abroad and thus brought a focus on the transnational to their liberation efforts. Marcelino dos Santos, the movement's unofficial diplomat, took the lead on international networking between the movement and other countries that provided aid.[53] They read Mao's works and thus adopted Maoist and Marxist-Leninist ideology at an early stage, even though the group's Marxist-Leninist affiliations were not made official until 1977.[51] As such, their approach to the war for independence was rooted in understanding of international liberation struggles, especially those by countries that would later align themselves with Marx-Leninism or communism. FRELIMO's fighting strategy was inspired by anti-colonial wars and other guerilla campaigns in China, South Vietnam and Algeria.[54]

FRELIMO was recognized early on by the Organization of African Unity (OAU), a group founded by Kwame Nkrumah and other African leaders, focused on eradicating colonialism and neocolonialism from the African continent.[55] The OAU provided funds in support of the independence fight.

Such support from other free nations on the African continent was crucial to the war effort. FRELIMO, and other Mozambican liberation groups that preceded it, were based in Tanzania because the character of Portuguese colonization under the Estado Novo was so repressive that it was nearly impossible for such resistance movements to begin and flourish in Mozambique proper.[54] When Tanzania gained independence in 1961, President Julius Nyerere permitted liberation movements in exile, including FRELIMO, to have the country as their base of operations.[56] On the African continent, FRELIMO received support from Tanzania, Algeria, and Egypt, among other independent nations.

In the spring of 1972, Romania allowed FRELIMO to open a diplomatic mission in Bucharest, the first of its kind in Eastern Europe. In 1973, Nicolae Ceaușescu recognized FRELIMO as "the only legitimate representative of the Mozambican people", an important precedent. Machel stressed that - during his trip to the Soviet Union - he and his delegation were granted "the status that we are entitled to" due to Romania's official recognition of FRELIMO. In terms of material support, Romanian trucks were used to transport weapons and ammunition to the front, as well as medicine, school material and agricultural equipment. Romanian tractors contributed to the increase in agricultural production. Romanian weapons and uniforms - reportedly of "excellent quality" - played a "decisive role" in FRELIMO's military progress. It was in early 1973 that FRELIMO made these statements about Romania's material support, in a memorandum sent to the Romanian Communist Party's Central Committee.[7]

During the Cold War, and particularly in the late 1950s, the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China adopted a strategy of destabilization of Western powers by disrupting their hold on African colonies.[57] Nikita Khrushchev, in particular, viewed the 'underdeveloped third of mankind' as a means to weaken the West. For the Soviets, Africa represented a chance to create a rift between western powers and their colonial assets, and create pro-communist states in Africa with which to foster future relations.[58] Prior to the formation of FRELIMO, the Soviet position regarding the nationalist movements in Mozambique was confused. There were multiple independence movements, and they had no sure knowledge that any would succeed.

The liberation movement's largely Marxist-Leninist principles and the eastern bloc's strategy of destabilization made Mozambican alliance with other left nations of the world seem like a foregone conclusion. Nationalist groups in Mozambique, like those across Africa during the period, received training and equipment from the Soviet Union.[59] But leaders of the movement for independence also wanted to balance their support. As such, they lobbied for and received support from both eastern bloc and non-aligned nations upon its consolidation into FRELIMO.[60] The movement was even initially supported by the U.S. government. In 1963, Mondlane met with Kennedy administration officials who later provided a $60,000 CIA subsidy in support of the movement. The Kennedy administration, however, rejected his request for military aid and by 1968 the Johnson administration severed all financial ties.[60]

Eduardo Mondlane's successor, future President of Mozambique, Samora Machel, acknowledged assistance from both Moscow and Peking, describing them as "the only ones who will really help us. They have fought armed struggles, and whatever they have learned that is relevant to Mozambique we will use."[61] Guerrillas received training in subversion and political warfare as well as military aid, specifically shipments of 122mm artillery rockets in 1972,[58] with 1,600 advisors from Russia, Cuba and East Germany.[62] Chinese military instructors also trained soldiers in Tanzania.[63]

Cuba's relationship with the Mozambican liberation movement was somewhat more fraught than that which FRELIMO fostered with the Soviet Union and China. Cuba had a similar interest in African wars for liberation as a potential locus for the spread of the ideology of the Cuban Revolution. The Cubans identified Mozambique's war for liberation as one of the most important ones occurring in Africa at the time.[64] But Cuba's efforts to make connection with FRELIMO were frustrated almost from the outset. In 1965, Mondlane met with Argentine marxist revolutionary Che Guevara in Dar es Salaam to discuss potential collaboration. The meeting ended acrimoniously when Guevara called into question the reports of FRELIMO's prowess, which it had greatly exaggerated in the press. Cubans also tried to convince FRELIMO to agree to train their guerillas in Zaire, which Mondlane refused. Eventually, these initial disagreements were resolved and Cubans agreed to train FRELIMO guerillas in Cuba and continued to provide weapons, food, and uniforms for the movement.[64] Cuba also acted as a conduit for communication between Mozambique and its fellow Portuguese colony Angola, and Latin American nations in the thrall of their own revolutionary movements such as Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala.[65]

European nations that provided FRELIMO with military and/or humanitarian support were Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands.[60] FRELIMO also had a small but significant network of support based in Reggio Emilia, Italy.[66]

The United States was non-involved in the conflict.[67]

Conflict

Insurgency under Mondlane (1964–69)

At the war's outset, FRELIMO had little hope for a conventional military victory, with a mere 7,000 combatants against a far larger Portuguese force. Their hopes rested on urging the local populace to support the insurgency, in order to force a negotiated independence from Lisbon.[37] Portugal fought its own version of protracted warfare, and a large military force was sent to quell the unrest, with troop numbers rising from 8,000 to 24,000 between 1964 and 1967.[68]

The military wing of FRELIMO was commanded by Filipe Samuel Magaia, whose forces received training from Algeria.[69] The FRELIMO guerrillas were armed with a variety of weapons, many provided by the Soviet Union and China. Common weapons included the Mosin–Nagant bolt-action rifle, SKS and AK-47 automatic rifles and the Soviet PPSh-41. Machine guns such as the Degtyarev light machine gun were widely used, along with the DShK and the SG-43 Gorunov. FRELIMO were supported by mortars, recoilless rifles, RPG-2s and RPG-7s, Anti-aircraft weapons such as the ZPU-4.[70]In the dying stages of the conflict, FRELIMO was provided with a few SA-7 MANPAD shoulder-launched missile launchers from China; these were never used to shoot down any Portuguese aircraft. Only one Portuguese aircraft was lost in combat during the conflict, when Lt. Emilio Lourenço's G.91R-4 was destroyed by premature detonation of his own ordnance.[69]

The Portuguese forces were under the command of General António Augusto dos Santos, a man with strong faith in new counter-insurgency theories. Augusto dos Santos supported a collaboration with Rhodesia to create African Scout units and other special forces teams, with Rhodesian forces even conducting their own independent operations during the conflict. Due to Portuguese policy of retaining up-to-date equipment for the metropole while shipping obsolete equipment to their overseas territories, the Portuguese soldiers fighting in the opening stages of the conflict were equipped with World War II radios and the old Mauser rifle. As the fighting progressed, the need for more modern equipment was rapidly recognised, and the Heckler & Koch G3 and FN FAL rifles were adopted as the standard battlefield weapon, along with the AR-10 for paratroopers. The MG42 and, then in 1968, the HK21 were the Portuguese general purpose machine guns, with 60, 81 and 120mm mortars, howitzers and the AML-60, Panhard EBR, Fox and Chaimite armoured cars frequently deployed for fire support.[70]

Start of FRELIMO attacks

In 1964, attempts at peaceful negotiation by FRELIMO were abandoned and, on September 25, Eduardo Mondlane began to launch guerrilla attacks on targets in northern Mozambique from his base in Tanzania.[50] FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in the province of Cabo Delgado. FRELIMO militants were able to evade pursuit and surveillance by employing classic guerrilla tactics: ambushing patrols, sabotaging communication and railroad lines, and making hit-and-run attacks against colonial outposts before rapidly fading into accessible backwater areas. The insurgents took full advantage of the monsoon season in order to evade pursuit.[37] During heavy rains, it was much more difficult to track insurgents by air, negating Portugal's air superiority, and Portuguese troops and vehicles found movement during rain storms difficult. In contrast, the insurgent troops, with lighter equipment, were able to flee into the bush (the mato) amongst an ethnically similar populace into which they could melt away. Furthermore, the FRELIMO forces were able to forage food from the surroundings and local villages, and were thus not hampered by long supply lines.[71]

With the initial FRELIMO attacks in Chai Chai, the fighting spread to Niassa and Tete at the centre of Mozambique. During the early stages of the conflict, FRELIMO activity was reduced to small, platoon-sized engagements, harassments and raids on Portuguese installations. The FRELIMO forces often operated in small groups of ten to fifteen guerillas. The scattered nature of FRELIMO's initial attacks was an attempt to disperse the Portuguese forces.

The Portuguese troops began to suffer losses in November, fighting in the northern region of Xilama. With increasing support from the populace, and the low number of Portuguese regular troops, FRELIMO was quickly able to advance south towards Meponda and Mandimba, linking to Tete with the aid of forces from the neighbouring Republic of Malawi, which had become a fully independent member of the Commonwealth of Nations on the 6 July 1964. Despite the increasing range of FRELIMO operations, attacks were still limited to small strike teams attacking lightly defended administrative outposts, with the FRELIMO lines of communication and supply utilising canoes along the Ruvuma River and Lake Malawi.[37]

It was not until 1965 that recruitment of fighters increased along with popular support, and the strike teams were able to increase in size. The increase in popular support was in part due to FRELIMO's offer of help to exiled Mozambicans, who had fled the conflict by travelling to nearby Tanzania.[37] Like similar conflicts against the French and United States forces in Vietnam, the insurgents also used landmines to a great extent to injure the Portuguese forces, thus straining the armed forces' infrastructure[73] and demoralising soldiers.[37]

FRELIMO attack groups had also begun to grow in size to include over 100 soldiers in certain cases, and the insurgents also began to accept women fighters into their ranks.[74] On either October 10 or October 11, 1966,[75] on returning to Tanzania after inspecting the front lines, Filipe Samuel Magaia was shot dead by Lourenço Matola, a fellow FRELIMO guerrilla who was said to be in the employ of the Portuguese.

One seventh of the population and one fifth of the territory were in FRELIMO hands by 1967;[76] at this time there were approximately 8000 guerrillas in combat.[37] During this period, Mondlane urged further expansion of the war effort, but also sought to retain the small strike groups. With the increasing cost of supply, more and more territory liberated from the Portuguese, and the adoption of measures to win the support of the population, it was at this time that Mondlane sought assistance from abroad, specifically the Soviet Union and China; from these benefactors, he obtained large-calibre machine guns, anti-aircraft rifles and 75 mm recoilless rifles and 122 mm rockets.[77] In 1967 East Germany agreed to begin supplying FRELIMO with military aid.[78] It equipped the organisation with various stocks of arms—many of which were weapons of World War II vintage—almost every year through the end of the war.[79]

In 1968, the second Congress of FRELIMO was a propaganda victory for the insurgents, despite attempts by the Portuguese, who enjoyed air superiority throughout the conflict, to bomb the location of the meeting late in the day.[37] This gave FRELIMO further weight to wield in the United Nations.[80]

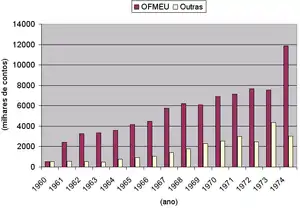

Portuguese development program

Due to both the technological gap between civilisations and the centuries-long colonial era, Portugal had been a driving force in the development of all of Portuguese Africa since the 15th century. In the 1960s and early 1970s, to counter the increasing insurgency of FRELIMO forces and show to the Portuguese people and the world that the territory was totally under control, the Portuguese government accelerated its major development program to expand and upgrade the infrastructure of Portuguese Mozambique by creating new roads, railways, bridges, dams, irrigation systems, schools and hospitals to stimulate an even higher level of economic growth and support from the populace.[45][81]

As part of this redevelopment program, construction of the Cahora Bassa Dam began in 1969. This particular project became intrinsically linked with Portugal's concerns over security in the overseas territories. The Portuguese government viewed the construction of the dam as testimony to Portugal's "civilising mission"[82] and intended for the dam to reaffirm Mozambican belief in the strength and security of the Portuguese overseas government. To this end, Portugal sent three thousand new troops and over one million landmines to Mozambique to defend the building project.

Realising the symbolic significance of the dam to the Portuguese, FRELIMO spent seven years attempting to halt its construction by force. No direct attacks were ever successful, but FRELIMO had some success in attacking convoys en route to the site.[37] FRELIMO also lodged a protest with the United Nations about the project, and their cause was aided by negative reports of Portuguese actions in Mozambique. In spite of the subsequent withdrawal of much foreign financial support for the dam, it was finally completed in December 1974. The dam's intended propaganda value to the Portuguese was overshadowed by the adverse Mozambican public reaction to the extensive dispersal of the indigenous populace, who were forced to relocate from their homes to allow for the construction project. The dam also deprived farmers of the critical annual floods, which formerly re-fertilised the plantations.[83]

Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane

On February 3, 1969, Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his office in Dar es Salaam. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel with a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.[84]

The original investigations levelled accusations at Silverio Nungo (who was later executed) and Lazaro Kavandame, FRELIMO leader in Cabo Delgado. The latter had made no secret of his distrust of Mondlane, seeing him as too conservative a leader, and the Tanzanian police also accused him of working with PIDE (Portugal's secret police) to assassinate Mondlane. Kavandame himself surrendered to the Portuguese in April of that year.[37]

Although the exact details of the assassination remain disputed, the involvement of the Portuguese government, particularly Aginter Press or PIDE, is generally accepted by most historians and biographers and is supported by the Portuguese stay behind Gladio-esque army, known as Aginter Press, that suggested in 1990 that they were responsible for the assassination. Initially, due to the uncertainty regarding who was responsible, Mondlane's death created great suspicion within the ranks of the FRELIMO itself and a short power struggle which resulted in a dramatic swing to the political left.[52][85]

Continuing war (1969–74)

In 1969, General António Augusto dos Santos was relieved of command, with General Kaúlza de Arriaga taking over officially in March 1970. Kaúlza de Arriaga favored a more direct method of fighting the insurgents, and the established policy of using African counter-insurgency forces was rejected in favor of the deployment of regular Portuguese forces accompanied by a small number of African fighters. Indigenous personnel were still recruited for special operations, such as the Special Groups of Parachutists in 1973, though their role less significant under the new commander. His tactics were partially influenced by a meeting with United States General William Westmoreland.[37][73]

By 1972 there was growing pressure from other commanders, particularly Kaúlza de Arriaga's second in command, General Francisco da Costa Gomes, for the use of African soldiers in Flechas units. Flechas units (Arrows) were also employed in Angola and were units under the command of the PIDE. Composed of local tribesmen, the units specialized in tracking, reconnaissance and anti-terrorist operations.[86]

Costa Gomes argued that African soldiers were cheaper and were better able to create a relationship with the local populace, a tactic similar to the 'hearts and minds' strategy being used by United States forces in Vietnam at the time. These Flechas units saw action in the territory at the very end stages of the conflict, following the dismissal of Arriaga on the eve of the Portuguese coup in 1974. The units were to continue to cause problems for the FRELIMO even after the Revolution and Portuguese withdrawal, when the country splintered into civil war.[87]

During the entire period of 1970–74, FRELIMO intensified guerrilla operations, specializing in urban terrorism.[37] The use of landmines also intensified, with sources stating that they had become responsible for two out of every three Portuguese casualties.[73] During the conflict, FRELIMO used a variety of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines, including the PMN (Black Widow), TM-46, and POMZ. Even amphibious mines were used, such as the PDM.[70] Mine psychosis, an acute fear of landmines, was rampant in the Portuguese forces. This fear, coupled with the frustration of taking casualties without ever seeing the enemy forces, damaged morale and significantly hampered progress.[37][73]

Portuguese counter-offensive (June 1970)

On June 10, 1970, a major counter-offensive was launched by the Portuguese army. Operation Gordian Knot (Portuguese: Operação Nó Górdio) targeted permanent insurgent camps and the infiltration routes across the Tanzanian border in the north of Mozambique over a period of seven months. The operation involved some 35,000 Portuguese troops,[37] particularly elite units like paratroopers, commandos, marines and naval fusiliers.[69]

Problems for the Portuguese arose almost immediately when the offensive coincided with the beginning of the monsoon season, creating additional logistical difficulties. Not only were the Portuguese soldiers badly equipped, but there was very poor cooperation, if any at all, between the FAP and the army. Thus, the army lacked close air support from the FAP. Mounting Portuguese casualties began to outweigh FRELIMO casualties, leading to further political intervention from Lisbon.

The Portuguese eventually reported 651 guerrillas as killed (a figure of some 440 was most likely closer to reality) and 1,840 captured, for the loss of 132 Portuguese soldiers. Arriaga also claimed his troops destroyed 61 guerrilla bases and 165 guerrilla camps, while 40 tons of ammunition had been captured in the first two months. Although "Gordian Knot" was the most effective Portuguese offensive of the conflict, weakening guerrillas to such a degree that they were no longer a significant threat, the operation was deemed a failure by some military officers and the government.

On December 16, 1972, the Portuguese 6th company of Commandos in Mozambique killed the inhabitants of the village of Wiriyamu, in the district of Tete.[37] Referred to as the 'Wiriyamu Massacre', the soldiers killed between 150 (according to the Red Cross) and 300 (according to a much later investigation by the Portuguese newspaper Expresso based in testimonies from soldiers) villagers accused of sheltering FRELIMO guerrillas. The action, "Operation Marosca", was planned at the instigation of PIDE agents and guided by agent Chico Kachavi, who was later assassinated while an inquiry into the events was being carried out. The soldiers were told by this agent that "the orders were to kill them all", never mind that only civilians, women and children included, were found.[88] All of the victims were civilians. The massacre was recounted in July 1973 by the British Catholic priest, Father Adrian Hastings, and two other Spanish missionary priests. Later counter-claims have been made in a report of Archbishop of Dar es Salaam Laurean Rugambwa that alleged that the killings were carried out by FRELIMO combatants, not Portuguese forces.[89] In addition, others claimed that the alleged massacres by Portuguese military forces were fabricated to tar the reputation of the Portuguese state abroad.[90] Portuguese journalist Felícia Cabrita reconstructed the Wiriyamu massacre in detail by interviewing both survivors and former members of the Portuguese Army Commandos unit that carried out the massacre. Cabrita's report was published in the Portuguese weekly newspaper Expresso and later in a book containing several of the journalist's articles.[91] On July 16, 1973, Zambia condemned the alleged massacres carried out by Portuguese troops.

By 1973, FRELIMO were also mining civilian towns and villages in an attempt to undermine the civilian confidence in the Portuguese forces.[37] "Aldeamentos: agua para todos" (Resettlement villages: water for everyone) was a commonly seen message in the rural areas, as the Portuguese sought to relocate and resettle the indigenous population, in order to isolate the FRELIMO from its civilian base.[92] Conversely, Mondlane's policy of mercy towards civilian Portuguese settlers was abandoned in 1973 by the new commander, Machel.[93] "Panic, demoralisation, abandonment, and a sense of futility—all were reactions among whites in Mozambique" stated conflict historian T. H. Henricksen in 1983.[73] This change in tactics led to protests by Portuguese settlers against the Lisbon government,[37] a telltale sign of the conflict's unpopularity. Combined with the news of the Wiriyamu Massacre and that of renewed FRELIMO onslaughts through 1973 and early 1974, the worsening situation in Mozambique later contributed to the downfall of the Portuguese government in 1974. A Portuguese journalist argued:

In Mozambique we say there are three wars: the war against FRELIMO, the war between the army and the secret police, and the central government.[94]

Political instability and ceasefire (1974–75)

Back in Lisbon, the 'Armed Revolutionary Action' branch of the Portuguese Communist Party, which was created in the late 1960s, and the Revolutionary Brigades (BR), a left-wing organisation, worked to resist the colonial wars. They had carried out multiple sabotages and bombings against military targets, such as the attack on the Tancos air base that destroyed several helicopters on March 8, 1971, and the attack on the NATO headquarters at Oeiras in October of the same year. The attack on the Portuguese ship Niassa illustrated the role of the colonial wars in this unrest. Niassa (named after the Mozambican province) was preparing to leave Lisbon with troops to be deployed in Guinea. By the time of the Carnation Revolution, 100,000 draft dodgers had been recorded.[39]

Fighting colonial wars in Portuguese colonies had absorbed forty-four percent of the overall Portuguese budget,[37][40][41] which led to a diversion of funds from infrastructure developments in Portugal, contributing to the growing unrest. The unpopularity of the Colonial Wars among many Portuguese led to the formation of magazines and newspapers, such as Cadernos Circunstância, Cadernos Necessários, Tempo e Modo, and Polémica, which had support from students and called for political solutions to Portugal's colonial problems. Dissatisfaction in Portugal culminated on April 25, 1974, when the Carnation Revolution, a peaceful leftist military coup d'état in Lisbon, ousted the incumbent Portuguese government of Marcello Caetano. Thousands of Portuguese citizens left Mozambique, and the new head of government, General António de Spínola, called for a ceasefire. With the change of government in Lisbon, many soldiers refused to continue fighting, often remaining in their barracks instead of going on patrol.[39] Negotiations between the Portuguese administration culminated in the Lusaka Accord signed on September 7, 1974, which provided for a complete hand-over of power to FRELIMO, uncontested by elections.[37] On Machel's demands, formal independence was set for June 25, 1975, the 13th anniversary of the founding of FRELIMO.[95]

Aftermath

Upon Mozambique's independence, Machel became the country's first president.[95] The new government was confronted with the issue of the comprometidos (compromised) Mozambicans—those who had worked for the Portuguese administration, particularly its security apparatus. After some delay, in the 1978 the government decided that, instead of imprisoning them, it would be required that their photos be posted at their places of work with captions describing their past actions. After about four years, the photos were removed, and in 1982 Machel hosted a national conference of comprometidos, during which they talked about their experiences.[96]

Many Portuguese colonists were not typical settlers in Mozambique. While most European communities in Africa at the time—with the exception of Afrikaners—were established from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, some white families and institutions in those territories still administered by Portugal had been entrenched for generations.[97][98] About 300,000 white civilians left Mozambique in the first week or two of independence (in Europe they were popularly known as retornados). With the departure of Portuguese professionals and tradesmen, Mozambique lacked an educated workforce to maintain its infrastructure, and economic collapse loomed.

Advisors from communist countries were brought in by the FRELIMO regime. Within about two years, fighting resumed with the Mozambican Civil War against RENAMO insurgents supplied with Rhodesian and South African military support. The Soviet Union and Cuba continued to support the new FRELIMO government against counterrevolution in the years after 1975. The United States' Ford administration had rebuffed Machel's desire to establish a trade relationship, effectively pushing Mozambique to align primarily with the eastern bloc.[60] By 1981, there were 230 Soviet, close to 200 Cuban military and over 600 civilian Cuban advisers still in the country.[58][99] Cuba's involvement in Mozambique was as part of a continuing effort to export the anti-imperialist ideology of the Cuban Revolution and forge desperately needed new allies. Cuba provided support to left wing rebels and governments in numerous African countries, including Angola, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau and Congo-Brazzaville.[100] In 1978, Mozambique sent some of its youth to be educated in Cuban schools.[101]

Industrial and social recession, corruption, poverty, inequality and failed central planning eroded the initial revolutionary fervour.[102] Single party rule by FRELIMO also became increasingly authoritarian throughout the Civil War.[103]

Mozambique's successful war for independence brought an end to the white-ruled cordon of nations separating Apartheid South Africa from the independent black-ruled nations of the continent.[104] As a result, newly independent nations such as Angola, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo acted as stages for proxy battles between capitalist and communist nations attempting to proliferate their respective ideologies.[105] Independent Mozambique, like Tanzania before it, served as a temporary base for African National Congress (ANC) operatives fighting to release South Africa from its white-led rule.[106]

Notes

- Frontiersmen: Warfare In Africa Since 1950, 2002. p. 49.

- Southern Africa The Escalation of a Conflict : a Politico-military Study, 1976. p. 99.

- Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken Autobiography, 2008. p. 315

- The Cuban Military Under Castro, 1989. p. 45

- Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa 607–623, 1967. p. 65.

- Underdevelopment and the Transition to Socialism: Mozambique and Tanzania, 2013. p. 38.

- Anna Calori, Anne-Kristin Hartmetz, Bence Kocsev, James Mark, Jan Zofka, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, Oct 21, 2019, Between East and South: Spaces of Interaction in the Globalizing Economy of the Cold War, pp. 133–134

- Ion Rațiu, Foreign Affairs Publishing Company, 1975, Contemporary Romania: Her Place in World Affairs, p. 90

- Liberalism, Black Power, and the Making of American Politics, 1965–1980. 2009. p. 83

- United Front against imperialism: China's foreign policy in Africa, 1986. p. 174

- Portuguese Africa: a handbook, 1969. p. 423.

- China Into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, 2009. p. 156.

- Tito in the world press on the occasion of the 80th birthday, 1973. p. 33.

- Mozambique, Resistance and Freedom: A Case for Reassessment, 1994. p. 64.

- Frelimo candidate Filipe Nyusi leading Mozambique presidential election

- Encyclopedia Americana: Sumatra to Trampoline, 2005. p. 275

- Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era, 2007. p. 226

- Moscow's Next Target in Africa by Robert Moss

- FRELIMO. Departamento de Informação e Propaganda, Mozambique revolution, Page 10

- Culture And Customs of Mozambique, 2007. p. 16

- Mozambique in the twentieth century: from colonialism to independence, 1979. p. 271

- A History of FRELIMO, 1982. p. 13

- Intercontinental Press, 1974. p. 857.

- The Last Bunker: A Report on White South Africa Today, 1976. p. 122

- Vectors of Foreign Policy of the Mozambique Front (1962–1975): A Contribution to the Study of the Foreign Policy of the People's Republic of Mozambique, 1988. p. 8

- Africa's Armies: From Honor to Infamy, 2009. p. 76

- Imagery and Ideology in U.S. Policy Toward Libya 1969–1982, 1988. p.. 70

- Qaddafi: his ideology in theory and practice, 1986. p. 140.

- South Africa in Africa: A Study in Ideology and Foreign Policy, 1975. p. 173.

- The dictionary of contemporary politics of Southern Africa, 1988. p. 250.

- Terror on the Tracks: A Rhodesian Story, 2011. p. 5.

- Kohn, George C. (2006). Dictionary of Wars. ISBN 978-1438129167.

- Chirambo, Reuben (2004). "'Operation Bwezani': The Army, Political Change, and Dr. Banda's Hegemony in Malawi" (PDF). Nordic Journal of African Studies. 13 (2): 146–163. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Salazar: A Political Biography, 2009. p. 530.

- Prominent African Leaders Since Independence, 2012. p. 383.

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. The Israeli connection: Whom Israel arms and why, p. 64. IB Tauris, 1987.

- Westfall, William C., Jr., United States Marine Corps, Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975, 1984. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Walter C. Opello, Jr. Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1974, p. 29

- Richard W. Leonard Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1974, p. 38

- George Wright, The Destruction of a Nation, 1996

- Phil Mailer, Portugal – The Impossible Revolution?, 1977

- Stewart Lloyd-Jones, ISCTE (Lisbon), Portugal's history since 1974, "The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP–Partido Comunista Português), which had courted and infiltrated the MFA from the very first days of the revolution, decided that the time was now right for it to seize the initiative. Much of the radical fervour that was unleashed following Spínola's coup attempt was encouraged by the PCP as part of their own agenda to infiltrate the MFA and steer the revolution in their direction.", Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, University of Coimbra

- Kennedy, Thomas. Mozambique, The Catholic Encyclopaedia. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- T. H. Henriksen, Remarks on Mozambique, 1975, p. 11

- Malyn D. D. Newitt, Mozambique Archived June 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine , Encarta. Retrieved on March 10, 2007. Archived November 1, 2009.

- Malyn Newitt, A History of Mozambique, 1995 p. 382

- Allen and Barbara Isaacman, Mozambique – From Colonialism to Revolution, Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1983, p. 58

- M. Bowen, The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique University Press Of Virginia; Charlottesville, Virginia, 2000

- J.M. Penvenne, Joao Dos Santos Albasini (1876–1922): The Contradictions of Politics and Identity in Colonial Mozambique, Journal of African History, 1996, number 37

- Malyn Newitt, A History of Mozambique, 1995 p. 517

- B. Munslow, editor, Samora Machel, an African Revolutionary: Selected Speeches and Writings, London: Zed Books, 1985

- Malyn Newitt, A History of Mozambique, 1995, p. 541

- Tornimbeni, Corrado (January 2, 2018). "Nationalism and Internationalism in the Liberation Struggle in Mozambique: The Role of the FRELIMO's Solidarity Network in Italy". South African Historical Journal. 70 (1): 196. doi:10.1080/02582473.2018.1433712. hdl:11585/622769. ISSN 0258-2473. S2CID 149196382.

- Kaiser, Daniel (January 2, 2017). "'Makers of Bonds and Ties': Transnational Socialisation and National Liberation in Mozambique". Journal of Southern African Studies. 43 (1): 45. doi:10.1080/03057070.2017.1274129. ISSN 0305-7070. S2CID 151672246.

- Arnold, Guy (2016). Wars in the Third World since 1945. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 41.

- Roberts, George (January 2, 2017). "The assassination of Eduardo Mondlane: FRELIMO, Tanzania, and the politics of exile in Dar es Salaam". Cold War History. 17 (1): 3. doi:10.1080/14682745.2016.1246542. ISSN 1468-2745. S2CID 157851744.

- Robert Legvold, Soviet Policy in West Africa, Harvard University Press, 1970, p. 1.

- Valentine J. Belfiglio. The Soviet Offensive in South Africa Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, airpower.maxwell, af.mil, 1983. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Kenneth W. Grundy, Guerrilla Struggle in Africa: An Analysis and Preview, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971, p. 51

- Schmidt, Elizabeth (2013). Foreign Intervention in Africa: from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 92.

- Brig. Michael Calvert, Counter-Insurgency in Mozambique in Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, no. 118, 1973

- U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to the Congress 1972

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. University of North Carolina Press. p. 227.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976. University of North Carolina Press. p. 87.

- Henighan, Stephen (September 2009). "The Cuban fulcrum and the search for a transatlantic revolutionary culture in Angola, Mozambique and Chile, 1965–2008". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 7 (3): 234. doi:10.1080/14794010903069078. ISSN 1479-4012. S2CID 143615518.

- Tornimbeni, Corrado (January 2, 2018). "Nationalism and Internationalism in the Liberation Struggle in Mozambique: The Role of the FRELIMO's Solidarity Network in Italy". South African Historical Journal. 70 (1): 199. doi:10.1080/02582473.2018.1433712. hdl:11585/622769. ISSN 0258-2473. S2CID 149196382.

- Zubovich, Gene (2023). "The U.S. Culture Wars Abroad: Liberal-Evangelical Rivalry and Decolonization in Southern Africa, 1968–1994". Journal of American History. 110 (2): 308–332. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaad261. ISSN 0021-8723.

The U.S. government largely stayed out of Mozambique's struggle for independence from 1962 to 1975 and its civil war from 1976 to 1992... the State Department remained neutral in these conflicts

- Borges Coelho, João Paulo. African Troops in the Portuguese Colonial Army, 1961–1974: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (PDF) Archived May 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Portuguese Studies Review 10 (1) (2002): 129–50, presented at the Portuguese/African Encounters: An Interdisciplinary Congress, Brown University, Providence MA, April 26–29, 2002. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Tom Cooper.Central, Eastern and South African Database, Mozambique 1962–1992, ACIG.org, September 2, 2003. Retrieved on March 7, 2007

- Cann, John P, Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961–1974, Hailer Publishing, 2005

- Walter C. Opello, Jr. Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1974, p. 29

- Mário Canongia Lopes, The Airplanes of the Cross of Christ, Lisbon: Dinalivro, 2000

- Thomas H. Henriksen, Revolution and Counterrevolution, London: Greenwood Press, 1983, p. 44

- Brendan F. Jundanian, The Mozambique Liberation Front, (Library of Congress: Institute Universitaire De Hautes Etupes Internacionales, 1970), p. 76–80

- Douglas L. Wheeler, A Document for the History of African Nationalism, 1970

- Brendan F. Jundanian, The Mozambique Liberation Front, (Library of Congress: Institut Universitaire De Hautes Etupes Internacionales, 1970), p. 70

- F. X. Maier, Revolution and Terrorism in Mozambique, New York: American Affairs Association, Inc., 1974, p. 12

- Storkmann 2010, p. 155.

- Storkmann 2010, pp. 155–156.

- F. X. Maier, Revolution and Terrorism in Mozambique, New York: American Affairs Association, Inc., 1974, p. 41

- (in Portuguese) Kaúlza de Arriaga (General), O Desenvolvimento de Moçaqmbique e a Promoção das Suas Populaçōes – Situaçāo em 1974, Kaúlza de Arriaga's published works and texts

- Allen Isaacman. Portuguese Colonial Intervention, Regional Conflict and Post-Colonial Amnesia: Cahora Bassa Dam, Mozambique 1965–2002, cornell.edu. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Richard Beilfuss. International Rivers Network Archived July 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine , 1999. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane Biography Archived September 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine , Oberlin College, revised September 2005 by Melissa Gottwald. Retrieved on February 16, 2000

- Walter C. Opello Jr, Pluralism and Elite Conflict in an Independence Movement: FRELIMO in the 1960s, part of Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1975, p. 66

- Roelof J. Kloppers : Border Crossings : Life in the Mozambique / South Africa Borderland since 1975. University of Pretoria. 2005. Online. Retrieved on March 13, 2007

- Brig. Michael Calvert, Counter-Insurgency in Mozambique, Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, no. 118, March 1973

- Gomes, Carlos de Matos, Afonso, Aniceto. Oa anos da Guerra Colonial – Wiriyamu, De Moçambique para o mundo. Lisboa, 2010

- Arslan Humbarachi & Nicole Muchnik, Portugal's African Wars, N.Y., 1974.

- Adrian Hastings, The Daily Telegraph (June 26, 2001)

- Cabrita, Felícia (2008). Massacres em África. A Esfera dos Livros, Lisbon. pp. 243–282. ISBN 978-989-626-089-7.

- Brendan F. Jundanian Resettlement Programs: Counterinsurgency in Mozambique, 1974, p. 519

- Kenneth R. Maxwell, The Making of Portuguese Democracy, 1995, p. 98

- F. X. Maier, Revolution and Terrorism in Mozambique, (New York: American Affairs Association Inc., 1974), p. 24

- Bueno 2021, p. 1019.

- Bueno 2021, pp. 1019, 1023.

- Robin Wright, White Faces In A Black Crowd: Will They Stay? Archived July 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine , The Christian Science Monitor (May 27, 1975)

- (in Portuguese) Carlos Fontes, Emigração Portuguesa Archived May 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Memórias da Emigração Portuguesa

- Gunn, Gillian (December 28, 1987). "CSIS Africa Notes: Cuba and Mozambique" (PDF).

- Sellström, Tor (1999). Liberation in Southern Africa : regional and Swedish voices : interviews from Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, the Frontline and Sweden (PDF) (2nd ed.). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. pp. 38–54. ISBN 91-7106-500-8. OCLC 54882811.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2013). Visions of Freedom : Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 85.

- Mario de Queiroz, Africa–Portugal: Three Decades After Last Colonial Empire Came to an End Archived June 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Borges Coelho, Joao Paulo (2013). "Politics and Contemporary History in Mozambique: A Set of Epistemological Notes". Kronos: Southern African Histories: 20–31. JSTOR 26432408.

- Arnold, Guy (1991). Wars in the Third World Since 1945. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 45. doi:10.5040/9781474291033. ISBN 978-1-4742-9102-6.

- Mentan, Tatah (2018). Africa in the Colonial Ages of Empire : Slavery, Capitalism, Racism, Colonialism, Decolonization. Oxford: Langaa RPCIG. p. 265.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2013). Visions of Freedom : Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 186.

References

Printed sources

- Bowen, Merle. The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique. University Press Of Virginia; Charlottesville, Virginia, 2000

- Calvert, Michael Brig. Counter-Insurgency in Mozambique from the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, no. 118, March 1973

- Cann, John P. Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961–1974, Hailer Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-313-30189-1

- Grundy, Kenneth W. Guerrilla Struggle in Africa: An Analysis and Preview, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971, ISBN 0-670-35649-2

- Henriksen, Thomas H. Remarks on Mozambique, 1975

- Legvold, Robert. Soviet Policy in West Africa, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1970, ISBN 0-674-82775-9

- Mailer, Phil. Portugal – The Impossible Revolution? 1977, ISBN 0-900688-24-6

- Munslow, Barry (ed.). Samora Machel, An African Revolutionary: Selected Speeches and Writings, London: Zed Books, 1985.

- Newitt, Malyn. A History of Mozambique, 1995, ISBN 0-253-34007-1

- Penvenne, J. M. "Joao Dos Santos Albasini (1876–1922): The Contradictions of Politics and Identity in Colonial Mozambique", Journal of African History, number 37.

- Wright, George. The Destruction of a Nation, 1996, ISBN 0-7453-1029-X

Online sources

- Belfiglio, Valentine J. (July–August 1983)The Soviet Offensive in Southern Africa, Air University Review. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Bueno, Natália (2021). "Different mechanisms, same result: Remembering the liberation war in Mozambique". Memory Studies. 14 (5): 1018–1034. doi:10.1177/1750698021995993. hdl:10316/95702. S2CID 233913128.

- Cooper, Tom. Central, Eastern and South African Database, Mozambique 1962–1992, ACIG, September 2, 2003. Retrieved on March 7, 2007

- Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (1920–1969), Oberlin College, revised in September 2005 by Melissa Gottwald. Retrieved on February 16, 2007

- Frelimo, Britannica.com. Retrieved on October 12, 2006

- Kennedy, Thomas (1911). "Mozambique". The Catholic Encyclopaedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Newitt, Malyn. Mozambique (Archived 2009-11-01), Encarta. Retrieved on February 16, 2007

- Storkmann, Klaus (2010). "Fighting the Cold War in southern Africa? East German military support to FRELIMO". Portuguese Journal of Social Science. 9 (2): 151–164. doi:10.1386/pjss.9.2.151_1.

- Thom, William G. (July–August 1974). Trends in Soviet Support for African Liberation, Air University Review. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Westfall, William C. Jr. (April 1, 1984). Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975. Retrieved on February 15, 2007

- Wright, Robin (May 12, 1975). Mondlane, Janet of the Mozambique Institute: American "Godmother" to an African Revolution. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

External links

- Guerra Colonial: 1961–1974 – State-supported historical site of the Portuguese Colonial War (Portugal) (in Portuguese)

- The official FRELIMO site (Mozambique)

- Time magazine, Dismantling the Portuguese Empire (in Portuguese)