SMS König Albert

SMS König Albert[lower-alpha 1] was the fourth vessel of the Kaiser class of dreadnought battleships of the Imperial German Navy.[lower-alpha 2] König Albert's keel was laid on 17 July 1910 at the Schichau-Werke dockyard in Danzig. She was launched on 27 April 1912 and was commissioned into the fleet on 31 July 1913. The ship was equipped with ten 30.5-centimeter (12 in) guns in five twin turrets, and had a top speed of 22.1 knots (40.9 km/h; 25.4 mph). König Albert was assigned to III Battle Squadron and later IV Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet for the majority of her career, including World War I.

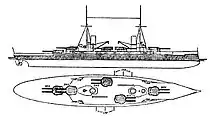

SMS König Albert; the diagonal lines along the side of the hull are anti-torpedo net booms. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | König Albert |

| Namesake | King Albert of Saxony |

| Builder | Schichau-Werke, Danzig |

| Laid down | 17 July 1910 |

| Launched | 27 April 1912 |

| Commissioned | 31 July 1913 |

| Fate | Scuttled at Gutter Sound, Scapa Flow 21 June 1919 |

| Notes | Raised in 1935 and broken up for scrapping 1936 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Kaiser-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 172.40 m (565 ft 7 in) |

| Beam | 29 m (95 ft 2 in) |

| Draft | 9.10 m (29 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 22.1 knots (40.9 km/h; 25.4 mph) |

| Range | 7,900 nmi (14,600 km; 9,100 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Crew |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Along with her four sister ships, Kaiser, Friedrich der Grosse, Kaiserin, and Prinzregent Luitpold, König Albert participated in most of the major fleet operations of World War I, though she was in drydock for maintenance during the Battle of Jutland between 31 May and 1 June 1916. As a result, she was the only battleship actively serving with the fleet that missed the largest naval battle of the war. The ship was also involved in Operation Albion, an amphibious assault on the Russian-held islands in the Gulf of Riga, in late 1917.

After Germany's defeat in the war and the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, König Albert and most of the capital ships of the High Seas Fleet were interned by the Royal Navy in Scapa Flow. The ships were disarmed and reduced to skeleton crews while the Allied powers negotiated the final version of the Treaty of Versailles. On 21 June 1919, days before the treaty was signed, the commander of the interned fleet, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, ordered the fleet to be scuttled to ensure that the British would not be able to seize the ships. König Albert was raised in July 1935 and subsequently broken up for scrap in 1936.

Design

The ship was 172.40 m (565 ft 7 in) long overall and displaced a maximum of 27,000 metric tons (26,570 long tons) at full load. She had a beam of 29 m (95 ft 2 in) and a draft of 9.10 m (29 ft 10 in) forward and 8.80 m (28 ft 10 in) aft. König Albert was powered by three sets of Schichau turbines, supplied with steam by sixteen coal-fired boilers. The powerplant produced a top speed of 22.1 knots (40.9 km/h; 25.4 mph). She carried 3,600 metric tons (3,500 long tons) of coal, which enabled a maximum range of 7,900 nautical miles (14,600 km; 9,100 mi) at a cruising speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). She had a crew of 41 officers and 1,043 enlisted.[1]

König Albert was armed with a main battery of ten 30.5 cm SK L/50 guns in five twin turrets.[1][lower-alpha 3] The ship disposed of the inefficient hexagonal turret arrangement of previous German battleships; instead, three of the five turrets were mounted on the centerline, with two of them arranged in a superfiring pair aft. The other two turrets were placed en echelon amidships, such that both could fire on the broadside.[3] The ship was also armed with a secondary battery of fourteen 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in casemates amidships. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 guns in casemates. The ship was also armed with four 8.8 cm L/45 anti-aircraft guns. The ship's armament was rounded out by five 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes, all mounted in the hull; one was in the bow, and the other four were on the broadside.[1]

Her main armored belt was 350 mm (13.8 in) thick in the central citadel, and was composed of Krupp cemented armor (KCA). Her main battery gun turrets were protected by 300 mm (11.8 in) of KCA on the sides and faces. König Albert's conning tower was heavily armored, with 400 mm (15.7 in) sides.[1]

Service history

Ordered under the contract name Ersatz Ägir as a replacement for the obsolete coastal defense ship SMS Ägir,[4][lower-alpha 4] König Albert was laid down at the Schichau-Werke dockyard in Danzig on 17 July 1910.[4] She was launched on 27 April 1912;[5] Princess Mathilde of Saxony christened the ship, and her brother, the last king of Saxony, Friedrich August III gave the speech.[6] Following the completion of fitting-out work, the ship was commissioned into the fleet on 31 July 1913.[5]

Although König Albert was the last ship in her class to be launched, she was the third to be commissioned,[5] owing to turbine damage on Kaiserin and delays on Prinzregent Luitpold's diesel engine.[7] The ship was selected to form part of the special Detached Division, alongside her sister Kaiser and the light cruiser Strassburg. The Division was placed under the command of Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz and sent on a tour of South America,[5] with the goals of testing the new turbine propulsion system and representing the growing power of the Imperial Navy.[1] The three ships left Wilhelmshaven on 9 December 1913 and steamed for German West Africa, where they made several stops, including Lomé, Togo, and Victoria and Duala, Kamerun. The Division then proceeded to German South-West Africa, making stops in Swakopmund and Lüderitzbucht, and South Africa, stopping in Saint Helena en route. On 15 February 1914, the Division reached Rio de Janeiro, which ceremonially greeted the visiting German warships.[8]

From Rio de Janeiro, Strassburg went to Buenos Aires, Argentina, while König Albert and Kaiser steamed to Montevideo, Uruguay. Strassburg then rejoined the battleships in Montevideo, and all three then rounded Cape Horn and steamed to Valparaíso, Chile. Between 2 and 11 April they remained in Valparaiso, which marked the furthest point of their journey. On the return voyage, the three ships made additional stops, including in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, before returning to Rio de Janeiro. The Division then began the trip back to Germany, stopping in Cape Verde, Madeira, and Vigo. The ships reached Kiel on 17 June 1914, after having traveled some 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km; 23,000 mi) without incident. On 24 June, the Detached Division was dissolved, and König Albert and Kaiser joined their classmates in III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet.[9]

World War I

Throughout the first two years of the war, the High Seas Fleet, including König Albert, conducted a number of sweeps and advances into the North Sea. The first occurred on 2–3 November 1914, though no British forces were encountered. Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, the commander of the High Seas Fleet, adopted a strategy in which the battlecruisers of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's I Scouting Group raided British coastal towns to lure out portions of the Grand Fleet where they could be destroyed by the High Seas Fleet.[10] The raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914 was the first such operation.[11] On the evening of 15 December, the German battle fleet of some twelve dreadnoughts—including König Albert and her four sisters—and eight pre-dreadnoughts came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. However, skirmishes between the rival destroyer screens in the darkness convinced Ingenohl that he was faced with the entire British Grand Fleet. Under orders from Kaiser Wilhelm II to avoid risking the fleet unnecessarily, Ingenohl broke off the engagement and turned back toward Germany.[12]

Following the loss of SMS Blücher at the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, the Kaiser removed Ingenohl from his post on 2 February. Admiral Hugo von Pohl replaced him as commander of the fleet.[13] Pohl conducted a series of fleet advances in 1915 in which König Albert took part; in the first one on 29–30 March, the fleet steamed out to the north of Terschelling and returned without incident. Another followed on 17–18 April, where König Albert and the rest of the fleet covered a mining operation by II Scouting Group. Three days later, on 21–22 April, the High Seas Fleet advanced toward the Dogger Bank, though again failed to meet any British forces.[14] On 15 May, a bushing came loose in the ship's starboard turbine, which forced the crew to turn the engine off and decouple it. The center and port side shafts were still capable of propelling the ship at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), however.[15] On 29–30 May, the fleet attempted to conduct a sweep in the North Sea, but inclement weather forced Pohl to cancel the operation some 50 nmi (93 km; 58 mi) off Schiermonnikoog. The fleet remained in port until 10 August, when it sortied to Helgoland to cover the return of the auxiliary cruiser Möwe. A month later, on 11–12 September, the fleet covered another mine-laying operation off the Swarte Bank. The last operation of the year, conducted on 23–24 October, was an advance in the direction of Horns Reef which concluded without result.[14]

On 11 January 1916, Admiral Reinhard Scheer replaced the ailing Pohl, who was suffering from liver cancer.[16] Scheer proposed a more aggressive policy designed to force a confrontation with the Grand Fleet; he received approval from the Kaiser in February.[17] The first of Scheer's operations was conducted the following month, on 5–7 March, with an uneventful sweep of the Hoofden.[18] On 25–26 March, Scheer attempted to attack British forces that had raided Tondern, but failed to locate them. Another advance to Horns Reef followed on 21–22 April.[14] On 24 April, the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group conducted a raid on the English coast. König Albert and the rest of the fleet sailed in distant support. The battlecruiser Seydlitz struck a mine while en route to the target, and had to withdraw.[19] The other battlecruisers bombarded the town of Lowestoft unopposed, but during the approach to Yarmouth, they encountered the British cruisers of the Harwich Force. A short artillery duel ensued before the Harwich Force withdrew. Reports of British submarines in the area prompted the retreat of I Scouting Group. At this point, Scheer, who had been warned of the sortie of the Grand Fleet from its base in Scapa Flow, also withdrew to safer German waters.[20]

After the raid on Yarmouth, several of the III Squadron battleships developed problems with their condensers.[21] This included König Albert; tubing needed to be replaced in all three main condensers, which necessitated extensive dockyard work. The ship went into drydock in the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven on 29 May, two days before the rest of the fleet departed for the Battle of Jutland. Work on the ship was not completed until 15 June,[15] and as a result, König Albert was the only German dreadnought in active service to miss the battle.[22] On 18 August 1916, König Albert took part in an operation to bombard Sunderland.[14] Admiral Scheer attempted a repeat of the original 31 May plan: the two serviceable German battlecruisers—Moltke and Von der Tann—augmented by three faster dreadnoughts, were to bombard the coastal town of Sunderland in an attempt to draw out and destroy Vice Admiral David Beatty's battlecruisers. Scheer would trail behind with the rest of the fleet and provide support.[23] During the action of 19 August 1916, Scheer turned north after receiving a false report from a zeppelin about a British unit in the area.[24] As a result, the bombardment was not carried out, and by 14:35, Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and so turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[25]

Another fleet operation took place on 18–19 October, though it ended without encountering any British units. Unit training in the Baltic was then conducted, and on the return voyage III Squadron was diverted to assist in the recovery of a pair of U-boats stranded on the Danish coast. The fleet was reorganized on 1 December;[15] the four König-class battleships remained in III Squadron, along with the newly commissioned Bayern, while the five Kaiser-class ships, including König Albert, were transferred to IV Squadron.[26] König Albert saw no major operations in the first half of 1917, and on 18 August she went into drydock at the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel for periodic maintenance, which lasted until 23 September.[15]

Operation Albion

In early September 1917, following the German conquest of the Russian port of Riga, the German naval command decided to eliminate the Russian naval forces that still held the Gulf of Riga.[27] On 18 September, the Admiralstab (the Navy High Command) issued the order for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands. The naval component, organized as a Special Unit (Sonderverband), was to comprise the flagship, Moltke, along with III and IV Battle Squadrons of the High Seas Fleet. Along with nine light cruisers, three torpedo boat flotillas, and dozens of mine warfare ships, the entire force numbered some 300 ships, supported by over 100 aircraft and six zeppelins.[28] Opposing the Germans were the old Russian pre-dreadnoughts Slava and Tsesarevich, the armored cruisers Bayan and Admiral Makarov, the protected cruiser Diana, 26 destroyers, and several torpedo boats and gunboats. The garrison on Ösel numbered some 14,000 men.[29]

The operation began on the morning of 12 October, when Moltke and the III Squadron ships engaged Russian positions in Tagga Bay while König Albert and the rest of IV Squadron shelled Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula on Ösel.[29] The coastal artillery in both locations were quickly silenced by the battleships' heavy guns.[30] On the morning of the 14th, König Albert, Friedrich der Grosse, and Kaiserin were detached to support German troops advancing toward Anseküll.[31] König Albert and Kaiserin were assigned to suppress a Russian battery at Zerel, though heavy fog delayed them from engaging the target. The Russians opened fire first, which was quickly returned by the two ships. Friedrich der Grosse came to the two ships' assistance and the three battleships fired a total of 120 large-caliber shells at the battery at Zerel over the span of an hour. The battleships' gunfire prompted most of the Russian gun crews to flee their posts.[32]

On the night of 15 October, König Albert and Kaiserin were sent to replenish their coal stocks in Putzig.[33] On the 19th, they were briefly joined in Putzig by Friedrich der Grosse, which continued on to Arensburg with Moltke.[34] The next morning, Vice Admiral Schmidt ordered the special naval unit to be dissolved; in a communique to the naval headquarters, Schmidt noted that "Kaiserin and König Albert can immediately be detached from Putzig to the North Sea."[35] The two ships then proceeded to Kiel via Danzig, where they transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal back to the North Sea.[5] After returning to the North Sea on 23 October, König Albert served as the flagship for a force of heavy ships, including Kaiserin, Nassau, Rheinland, and the battlecruiser Derfflinger, supporting a mine-sweeping operation in the German Bight. Afterward she resumed guard duty in the Bight.[15]

Fate

König Albert and her four sisters were to have taken part in a final fleet action at the end of October 1918, days before the Armistice was to take effect. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to retain a better bargaining position for Germany, despite the expected casualties. However, many of the war-weary sailors felt the operation would disrupt the peace process and prolong the war.[36] On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied.[37] The ship remained on picket duty in the Bight until 10 November. This kept her away from the mutinous vessels, until she returned to port and her crew joined the mutiny.[15] The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[38] Informed of the situation, the Kaiser stated "I no longer have a navy."[39]

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow.[38] Prior to the departure of the German fleet, Admiral Adolf von Trotha made it clear to Reuter that he could not allow the Allies to seize the ships, under any conditions.[40] The fleet rendezvoused with the British light cruiser Cardiff, which led the ships to the Allied fleet that was to escort the Germans to Scapa Flow. This consisted of some 370 British, American, and French warships.[41] Once the ships were interned, their guns were disabled through the removal of their breech blocks, and their crews were reduced to 200 officers and enlisted men.[42]

The fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Treaty of Versailles. Reuter believed that the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. Unaware that the deadline had been extended to the 23rd, Reuter ordered the ships to be sunk at the next opportunity. On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.[40] König Albert capsized and sank at 12:54. On 31 July 1935, the ship was raised and broken up for scrap over the following year in Rosyth.[1]

Notes

Footnotes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- König Albert was the fourth of five ships ordered, but she was completed after the fifth ship, Prinzregent Luitpold. See Gröner, p. 26. As a result, some sources refer to König Albert as the fifth ship of the class. See Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 109.

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick loading, while the L/50 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/50 gun is 50 calibers, meaning that the gun is 45 times as long as it is in bore diameter.[2]

- German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

Citations

- Gröner, p. 26.

- Grießmer, p. 177.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 4.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 6.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 20.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 109.

- Staff, Battleships, pp. 18, 22.

- Staff, Battleships, pp. 10, 11.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 11.

- Herwig, pp. 149–150.

- Tarrant, p. 31.

- Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- Tarrant, pp. 43–44.

- Staff, Battleships, pp. 15, 21.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 21.

- Tarrant, p. 49.

- Tarrant, p. 50.

- Staff, Battleships, pp. 32, 35.

- Tarrant, p. 53.

- Tarrant, p. 54.

- Tarrant, p. 56.

- Tarrant, p. 62.

- Massie, p. 682.

- Staff, Battleships, p. 15.

- Massie, p. 683.

- Halpern, p. 214.

- Halpern, p. 213.

- Halpern, pp. 214–215.

- Halpern, p. 215.

- Barrett, p. 125.

- Barrett, p. 146.

- Staff, Battle for the Baltic Islands, pp. 71–72.

- Staff, Battle for the Baltic Islands, p. 81.

- Staff, Battle for the Baltic Islands, p. 140.

- Staff, Battle for the Baltic Islands, p. 145.

- Tarrant, pp. 280–281.

- Tarrant, pp. 281–282.

- Tarrant, p. 282.

- Herwig, p. 252.

- Herwig, p. 256.

- Herwig, pp. 254–255.

- Herwig, p. 255.

References

- Barrett, Michael B. (2008). Operation Albion. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34969-9.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Band 5) [The German Warships (Volume 5)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 2: Kaiser, König And Bayern Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-468-8.

- Staff, Gary (2008) [1995]. Battle for the Baltic Islands 1917: Triumph of the Imperial German Navy. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.