SMS Kaiser Karl VI

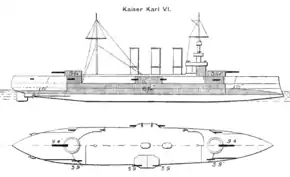

SMS Kaiser Karl VI ("His Majesty's Ship Kaiser Karl VI")[lower-alpha 1] was the second of three armored cruisers built by the Austro-Hungarian Navy. She was built by the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino in Trieste between June 1896 and May 1900, when she was commissioned into the fleet. Kaiser Karl VI represented a significant improvement over the preceding design—Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia—being faster and more heavily armed and armored. She provided the basis for the third design, Sankt Georg, which featured further incremental improvements. Having no overseas colonies to patrol, Austria-Hungary built the ship solely to reinforce its battle fleet.

SMS Kaiser Karl VI | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia |

| Succeeded by | Sankt Georg |

| History | |

| Builder | Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino |

| Laid down | 1 June 1896 |

| Launched | 4 October 1898 |

| Commissioned | 23 May 1900 |

| Decommissioned | 1918 |

| Fate | Ceded to Britain as a war prize; scrapped in 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Armored cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 118.96 m (390 ft 3 in) |

| Beam | 17.27 m (56 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 6.75 m (22 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | 20.83 knots (38.58 km/h; 23.97 mph) |

| Complement | 535 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

Kaiser Karl VI spent the first decade in service rotating between the training and reserve squadrons, alternating with Sankt Georg. In 1910, Kaiser Karl VI went on a major overseas cruise to South America, visiting Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina; this was the last trans-Atlantic voyage of an Austro-Hungarian warship. After the outbreak of war, she was mobilized into the Cruiser Flotilla, which spent the majority of the war moored at Cattaro. The lengthy inactivity eventually led to the Cattaro Mutiny in February 1918, which the crew of Kaiser Karl VI joined. After the mutiny collapsed, Kaiser Karl VI and several other warships were decommissioned to reduce the number of idle sailors. After the war, she was allocated as a war prize to Britain and was sold to ship-breakers in Italy, where she was scrapped in 1920.

Design

Starting in the mid-1880s, the new Austro-Hungarian Marinekommandant (Navy Commander), Vizeadmiral (Vice Admiral) Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck, began a reorientation of Austro-Hungarian naval strategy. The fleet had until then been centered on large ironclad warships, but had been unable to continue building vessels of that type under the direction of the previous Marinekommandant, Vizeadmiral Friedrich von Pöck, owing to the refusal of the Imperial Council of Austria and the Diet of Hungary to grant sufficient naval budgets. Sterneck decided to adopt the concepts espoused by the French Jeune École (Young School), which suggested that flotillas of cheap torpedo boats could effectively defend a coastline against a fleet of expensive battleships. The torpedo boats would be supported by what Sterneck termed "torpedo-ram-cruisers", which would protect the torpedo boats from enemy cruisers.[1][2]

In his fleet plan for 1891, Sterneck proposed that the future Austro-Hungarian fleet would consist of four squadrons, each consisting of one torpedo-ram-cruiser, a smaller torpedo cruiser, a large torpedo boat and six smaller torpedo boats. The first three of these squadrons would be led by the two Kaiser Franz Joseph I-class protected cruisers and the armored cruiser Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia, and in 1891 the design staff began work on the fourth cruiser. Three proposals were considered, the first modeled on Kaiser Franz Joseph I, the second on the small protected cruiser Panther, and the last derived from the British armored cruiser HMS Royal Arthur. All three designs displaced 5,090 long tons (5,170 t). But by the time work on Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia began that year, naval officers who opposed Sterneck's theories forced him to postpone the fourth cruiser in favor of beginning work on a new generation of capital ships, what would become the Monarch-class coastal defense ships.[3]

Those opposed to Sterneck believed the new cruisers should be formed into their own squadron to serve with the main battle fleet, and so in 1894, began preparations to build another armored cruiser. Three competing designs were submitted, two by the naval architect Josef Kellner and the third by Viktor Lollok. Kellner's initial design was for a 5,800-long-ton (5,900 t) ship similar to Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia, armed with the same battery of two 24 cm (9.4 in) guns and eight 15 cm (5.9 in) guns. The second was broadly similar with the same but differently arranged armament, and displacement increased to 6,000 long tons (6,100 t) and two funnels instead of the one in his other design. Lollok's proposal was also 6,000 tons, and instead of carrying all eight 15 cm guns in main-deck casemates, four would be moved up to open mounts on the upper deck.[4]

The naval command selected Kellner's second design, although it mandated a change to water-tube boilers for increased engine power, which in turn necessitated the addition of a third funnel. She also received the latest version of 24 cm guns manufactured by the German firm Krupp: the longer-barreled SK L/40 C/94 version. The new cruiser, named Kaiser Karl VI, was about 1,000 long tons (1,000 t) larger than her predecessor, Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia, and was a significantly more effective vessel as a result, being a knot faster, mounting more powerful guns, and carrying heavier armor.[5]

General characteristics and machinery

Kaiser Karl VI was 117.9 meters (386 ft 10 in) long at the waterline and was 118.96 m (390 ft 3 in) long overall. She had a beam of 17.27 m (56 ft 8 in) and a draft of 6.75 m (22 ft 2 in). She displaced 6,166 long tons (6,265 t) as designed and up to 6,864 long tons (6,974 t) at full load. Having gained experience with the stability problems caused by Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia's military masts, Kaiser Karl VI was completed with lighter pole masts and a significantly smaller superstructure. Her crew varied between 535 and 550 officers and men over the course of her career. Kaiser Karl VI was fitted with two pole masts for observation.[6][7]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of two 4-cylinder triple-expansion engines that drove a pair of screw propellers.[6] The engines were built at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT) shipyard in Trieste that built the ship. Steam was provided by sixteen water-tube Belleville boilers manufactured by Maudslay, Sons and Field of Britain.[8][9] The engines were rated at 12,000 indicated horsepower (8,900 kW) for a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), though on trials they produced a top speed of 20.83 knots (38.58 km/h; 23.97 mph). Coal storage amounted to 500 long tons (510 t) normally and up to 818 long tons (831 t) under wartime loading.[6][9]

Armament and armor

Kaiser Karl VI was armed with a main battery of two large-caliber guns and several medium-caliber pieces. She carried two 24 cm L/40 C/94 guns manufactured by Krupp in single gun turrets on the centerline, one forward and one aft. A secondary battery of eight 15 cm (5.9 in) L/40 guns mounted individually in casemates rounded out her offensive armament; these were carried in the main deck, two on either side amidships, sponsoned out over the hull, and two abreast both of the main battery turrets. She was armed with sixteen 47 mm (1.9 in) L/44 guns built by Škoda and two 4.7 cm L/33 Hotchkiss guns for close-range defense against torpedo boats. She carried several smaller weapons, including a pair of 8-millimeter (0.31 in) machine guns and two 7 cm (2.8 in) L/18 landing guns. Kaiser Karl VI was also equipped with a pair of 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside.[6][9]

The ship's armor consisted of Harvey armor.[5] She was protected by a main armored belt that was 220 mm (8.7 in) thick in the central portion that protected the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces, and reduced to 170 mm (6.7 in) on either end. She had an armored deck that was 40 to 60 mm (1.6 to 2.4 in) thick. Her two gun turrets had 200 mm (7.9 in) thick faces, and the 15 cm guns had 80 mm (3.1 in) thick casemates. The conning tower had 200 mm thick sides and a 100 mm (3.9 in) thick roof.[6]

Service history

Named for the 18th-century Holy Roman Emperor, Karl VI, Kaiser Karl VI was built at the STT shipyard in Trieste. Her keel was laid on 1 June 1896 and her completed hull was launched on 4 October 1898. Fitting-out work then commenced, which lasted until 23 May 1900, when the ship was commissioned into the Austro-Hungarian fleet.[6] Starting from her commissioning, Kaiser Karl VI frequently served in the training squadron, along with the three Habsburg-class battleships, though she alternated in the squadron with the armored cruiser Sankt Georg. Once the summer training schedule was completed each year, the ships of the training squadron were demobilized in the reserve squadron, which was held in a state of partial readiness.[10] In 1900, she served as the flagship of then-Rear Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli in the training squadron, along with Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia.[11] During the summer maneuvers of June 1901, she served as the flagship of Rear Admiral G. Ritter von Brosch, commander of the reserve squadron. The other major ships in the squadron included the old ironclad Tegetthoff and the cruiser Kaiser Franz Joseph I.[12]

In mid-1910, Kaiser Karl VI conducted the last trans-Atlantic cruise of an Austrian vessel, when she visited Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. On 25 May, she represented Austria-Hungary at the centennial of Argentina's May Revolution, which won the country's independence from Spain.[13]

World War I

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo; the assassination sparked the July Crisis and ultimately the First World War, which broke out a month later on 28 July. The German battlecruiser SMS Goeben, which had been assigned to the Mediterranean Division, sought the protection of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, and so Admiral Anton Haus sent the fleet, including Kaiser Karl VI, south on 7 August to assist his German ally. Goeben's commander, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, intended to use the Austro-Hungarian move as a feint to distract the British Mediterranean Fleet which was pursuing Goeben; Souchon instead took his ship to Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire. Their decoy mission complete, Kaiser Karl VI and the rest of the fleet returned to port without engaging any British forces.[14]

On 8 August, Montenegrin gun batteries on Mount Lovćen began shelling the Austro-Hungarian at Cattaro. At the time, Kaiser Karl VI was the only large warship in the harbor, and so she assisted the local army artillery in attempting to suppress the hostile guns. The Austro-Hungarian gunners were aided by navy seaplanes that could spot the fall of their shots. On 13 September, the three Monarch-class coastal defense ships arrived to strengthen the Austro-Hungarian force. Five days later, a French artillery battery was landed in Montenegro to reinforce the guns on Lovćen with the aim of eventually capturing the port, which prompted the Austro-Hungarians to send the pre-dreadnought battleship Radetzky with its 30.5 cm (12 in) guns. By 27 October, the French and Montenegrin gun batteries had been silenced, and the French abandoned its attempt to seize Cattaro.[15]

By the end of August, the mobilization of the fleet was complete; Kaiser Karl VI was assigned to the Cruiser Flotilla, which was commanded by Vice Admiral Paul Fiedler.[16] For most of the war, the Cruiser Flotilla and based at Cattaro, though the armored cruisers were too slow to operate with the newer Novara-class cruisers that carried out the bulk of offensive operations.[17] In May 1915, Italy declared war on the Central Powers. The Austro-Hungarians continued their strategy of serving as a fleet in being, which would tie down the now further numerically superior Allied naval forces. Haus hoped that torpedo boats and mines could be used to reduce the numerical superiority of the Italian fleet before a decisive battle could be fought.

By early 1918, the long periods of inactivity had begun to wear on the crews of several warships at Cattaro, including Kaiser Karl VI. On 1 February, the Cattaro Mutiny broke out, starting aboard Sankt Georg and quickly spreading to Kaiser Karl VI.[19] Officers were confined to their quarters while a committee of sailors met to formulate a list of demands, which ranged from longer periods of leave and better rations to an end to the war, based on the United States President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. The following day, shore batteries loyal to the government fired on the old ironclad Kronprinz Erzherzog Rudolf, which prompted many of the mutinous ships to abandon the effort. Late in the day on 2 February, the red flags were struck from Kaiser Karl VI and she rejoined the loyalist ships in the harbor. The next morning, the Erzherzog Karl-class battleships of the III Division arrived in Cattaro, which convinced the last holdouts to surrender. Trials on the ringleaders commenced quickly and four men were executed.[20][21]

Fate

In the aftermath of the Cattaro Mutiny, most of the obsolete warships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, including Kaiser Karl VI, were decommissioned to reduce the number of idle warships. On 3 November 1918, the Austro-Hungarian government signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti with Italy, ending their participation in the conflict.[23] After the end of the war, Kaiser Karl VI was ceded as a war prize to Great Britain, under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. She was then sold to ship breakers in Italy and broken up for scrap after 1920.[6]

Notes

Footnotes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

Citations

- Sondhaus, pp. 51–53.

- Dodson, p. 46.

- Dodson, pp. 46–47, 66.

- Dodson, pp. 47, 66.

- Dodson, p. 66.

- Sieche & Bilzer, p. 273.

- Dodson, pp. 47, 170.

- Sondhaus, p. 160.

- Dodson, p. 170.

- Sondhaus, pp. 172–173.

- Garbett 1900, p. 808.

- Garbett 1901, p. 1130.

- Sondhaus, p. 185.

- Sondhaus, pp. 245–249.

- Noppen, pp. 28–30.

- Sondhaus, p. 257.

- Sondhaus, p. 303.

- Halpern Cattaro Mutiny, pp. 49–50.

- Sondhaus, pp. 318–324.

- Halpern Cattaro Mutiny, pp. 52–53.

- Sieche 1985, p. 329.

References

- Dodson, Aidan (2018). Before the Battlecruiser: The Big Cruiser in the World's Navies, 1865–1910. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4738-9216-3.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1900). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLIV: 803–813.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1901). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLV: 1124–1139.

- Halpern, Paul (1994). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-266-6.

- Halpern, Paul (2004). "The Cattaro Mutiny, 1918". In Bell, Christopher M.; Elleman, Bruce A. (eds.). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. London: Frank Cass. pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-0-7146-5460-7.

- Noppen, Ryan (2012). Austro-Hungarian Battleships, 1914–18. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-688-2.

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1990). "Austria-Hungary's Last Visit to the USA". Warship International. XXVII (2): 142–164. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sieche, Erwin (1985). "Austria-Hungary". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 326–347. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Sieche, Erwin & Bilzer, Ferdinand (1979). "Austria-Hungary". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 266–283. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

Further reading

- Greger, René (1976). Austro-Hungarian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0623-7.

- Sieche, Erwin (2002). Kreuzer und Kreuzerprojekte der k.u.k. Kriegsmarine 1889–1918 [Cruisers and Cruiser Projects of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1889–1918] (in German). Hamburg. ISBN 978-3-8132-0766-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)