Sheba

Sheba (/ˈʃiːbə/; Hebrew: שְׁבָא Šəḇāʾ; Arabic: سبأ Sabaʾ; Ge'ez: ሳባ Saba) is a kingdom mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Quran. Sheba features in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions, particularly the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo tradition. It was the home of the biblical "Queen of Sheba", who is left unnamed in the Bible, but receives the names Makeda in Ethiopian and Bilqīs in Arabic tradition. According to Josephus it was also the home of the biblical "Princess Tharbis" said to have been the first wife of Moses when he was still a prince of Egypt.

| Sheba | |

|---|---|

| Native name Musnad: 𐩪𐩨𐩱 | |

| |

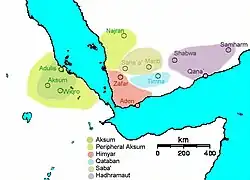

There are competing claims of where this kingdom was, with modern scholars placing it in the regions of South Arabia and the Horn of Africa.

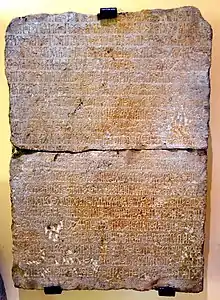

Encyclopedia Britannica posits that the biblical narrative about the kingdom of Sheba was based on the ancient civilization of Saba (Old South Arabian: 𐩪𐩨𐩱 S-b-ʾ) in South Arabia.[1] This view is echoed by Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman who write that "the Sabaean kingdom began to flourish only from the eighth century BCE onward" and that the story of Solomon and Sheba is "an anachronistic seventh-century set piece meant to legitimize the participation of Judah in the lucrative Arabian trade".[2]

Biblical tradition

The two names Sheba (spelled in Hebrew with shin) and Seba (spelled with samekh) are mentioned several times in the Bible with different genealogy. For instance, in the Generations of Noah[3] Seba, along with Dedan, is listed as a descendant of Noah's son Ham (as sons of Raamah, son of Cush). Later on in the Book of Genesis,[4] Sheba and Dedan are listed as names of sons of Jokshan, son of Abraham. Another Sheba is listed in the Table of Nations[5] as a son of Joktan, another descendant of Noah's son Shem.

There are several possible reasons for this confusion. One theory is that the Sabaeans established many colonies to control the trade routes and the variety of their caravan stations confused the ancient Israelites, as their ethnology was based on geographical and political grounds and not necessarily racial.[6] Another theory suggests that the Sabaeans hailed from the southern Levant and established their kingdom on the ruins of the Minaeans.[7]

The most famous claim to fame for the biblical land of Sheba was the story of the Queen of Sheba, who travelled to Jerusalem to question King Solomon, arriving in a large caravan with precious stones, spices and gold (1 Kings 10). The apocryphal Christian Arabic text Kitāb al-Magall ("Book of the Rolls"),[8] considered part of Clementine literature, and the Syriac Cave of Treasures, mention a tradition that after being founded by the children of Saba (son of Joktan), there was a succession of 60 female rulers up until the time of Solomon.

Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, describes a place called Saba as a walled, royal city of Ethiopia that Cambyses II renamed as Meroë. He writes that "it was both encompassed by the Nile quite round, and the other rivers, Astapus and Astaboras", offering protection from both foreign armies and river floods. According to Josephus it was the conquering of Saba that brought great fame to a young Egyptian prince, simultaneously exposing his personal background as a slave child named Moses.[9]

Muslim tradition

In the Quran, Sheba is mentioned in surat an-Naml in a section that speaks of the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon.[10] The Quran mentions this ancient community along with other communities that were destroyed by God.[11]

_Enthroned_-_Walters_W6313A_-_Full_Page.jpg.webp)

In the Quran, the story essentially follows the Bible and other Jewish sources.[12] Solomon commanded the Queen of Sheba to come to him as a subject, whereupon she appeared before him (an-Naml, 30–31, 45). Before the queen had arrived, Solomon had moved her throne to his place with the help of one who had knowledge from the scripture (Quran 27:40). She recognized the throne, which had been disguised, and finally accepted the faith of Solomon.

Muslim commentators such as al-Tabari, al-Zamakhshari, al-Baydawi supplement the story at various points. The Queen's name is given as Bilqis, probably derived from Greek παλλακίς or the Hebraised pilegesh, "concubine".[13] According to some he then married the Queen, while other traditions assert that he gave her in marriage to a tubba of Hamdan.[14] According to the Islamic tradition as represented by al-Hamdani, the queen of Sheba was the daughter of Ilsharah Yahdib, the Himyarite king of Najran.[15]

Although the Quran and its commentators have preserved the earliest literary reflection of the complete Bilqis legend, there is little doubt among scholars that the narrative is derived from a Jewish Midrash.[14]

Bible stories of the Queen of Sheba and the ships of Ophir served as a basis for legends about the Israelites traveling in the Queen of Sheba's entourage when she returned to her country to bring up her child by Solomon.[16] There is a Muslim tradition that the first Jews arrived in Yemen at the time of King Solomon, following the politico-economic alliance between him and the Queen of Sheba.[12]

Muslim scholars, including Ibn Kathir, related that the people of Sheba were Arabs from South Arabia.[17]

Ethiopian and Yemenite tradition

In the medieval Ethiopian cultural work called the Kebra Nagast, Sheba was located in Ethiopia.[18] Some scholars therefore point to a region in the northern Tigray and Eritrea which was once called Saba (later called Meroe), as a possible link with the biblical Sheba.[19] Donald N. Levine links Sheba with Shewa (the province where modern Addis Ababa is located) in Ethiopia.[20]

Traditional Yemenite genealogies also mention Saba, son of Qahtan; Early Islamic historians identified Qahtan with the Yoqtan (Joktan) son of Eber (Hūd) in the Hebrew Bible (Gen. 10:25-29). James A. Montgomery finds it difficult to believe that Qahtan was the biblical Joktan based on etymology.[21][22]

Speculation on location

Modern historians agree that the heartland of the Sabaean civilization was located in the region around Marib and Sirwah, in what is now Yemen.[23][24] They later expanded their presence into parts of North Arabia[24] and the Horn of Africa, in modern-day Ethiopia.[25]

Owing to the connection with the Queen of Sheba, the location has become closely linked with national prestige, and various royal houses claimed descent from the Queen of Sheba and Solomon. According to the medieval Ethiopian work Kebra Nagast, Sheba was located in Ethiopia. Ruins in many other countries, including Sudan, Egypt, Oman and Iran have been credited as being Sheba, but with only minimal evidence.

See also

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Sabaʾ

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2007). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Simon & Schuster. p. 171.

- Genesis 10:7.

- Genesis 25:3.

- Genesis 10:28.

- Javad Ali, The Articulate in the History of Arabs before Islam Volume 7, p. 421.

- HOMMEL, Südarabische Chrestomathie (Munich, 1892), p. 64.

- "Kitab al-Magall".

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews II.10.

- Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- Qur'an 50:14

- Yosef Tobi (2007), "QUEEN OF SHEBA", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 16 (2nd ed.), Gale, p. 765

- Georg Freytag (1837), "ﺑَﻠٔﻘَﻊٌ", Lexicon arabico-latinum, Schwetschke, p. 44a

- E. Ullendorff (1991), "BILḲĪS", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Brill, pp. 1219–1220

- A. F. L. Beeston (1995), "SABAʾ", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 8 (2nd ed.), Brill, pp. 663–665

- Haïm Zʿew Hirschberg; Hayyim J. Cohen (2007), "ARABIA", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 3 (2nd ed.), Gale, p. 295

- Brannon M. Wheeler. "People of the Well". A-Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism.

- Edward Ullendorff, Ethiopia and the Bible (Oxford: University Press for the British Academy, 1968), p. 75

- The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant: The True History of the Tablets of Moses, by Stuart Munro-Hay

- Donald N. Levine, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopia Culture (Chicago: University Press, 1972).

- Maalouf, Tony (2003). "The Unfortunate Beginning (Gen. 16:1–6)". Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. p. 45. ISBN 9780825493638. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

This view is largely based on the claim of Muslim Arab historians that their oldest ancestor is Qahtan, whom they identify as the biblical Joktan (Gen. 10:25–26). Montgomery finds it difficult to reconcile Joktan with Qahtan based on etymology.

- Maqsood, Ruqaiyyah Waris. "Adam to the Banu Khuza'ah". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

- Michael Wood, "The Queen Of Sheba", BBC History.

- Nebes 2023, p. 299.

- Nebes 2023, pp. 348, 350.

Bibliography

- Alessandro de Maigret. Arabia Felix, translated Rebecca Thompson. London: Stacey International, 2002. ISBN 1-900988-07-0

- Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-922237-1.

- Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3-447-03679-6.

- Kenneth A. Kitchen: The World of Ancient Arabia Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework & Historical Sources. Liverpool 1994.

- Walter W. Müller: Skizze der Geschichte Altsüdarabiens. In: Werner Daum (ed.): Jemen. Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck / Umschau-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1987, OCLC 17785905, S. 50–56.

- Walter W. Müller (Hrsg.), Hermann von Wissmann: Die Geschichte von Sabaʾ II. Das Grossreich der Sabäer bis zu seinem Ende im frühen 4. Jh. v. Chr. (= Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften,Philosophisch-historische Klasse. Sitzungsberichte. Vol. 402). Vienna: Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1982, ISBN 3-7001-0516-9.

- Nebes, Norbert (2023). "Early Saba and Its Neighbors". In Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, D. T. (eds.). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: The Age of Persia. Vol. 5. Oxford University Press. pp. 299–375. ISBN 978-0-19-068766-3.

- Jaroslav Tkáč: Saba 1. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). Band I A,2, Stuttgart, 1920, Pp. 1298–1511.

- Hermann von Wissmann: Zur Geschichte und Landeskunde von Alt-Südarabien (Sammlung Eduard Glaser. Nr. III = Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Klasse, Sitzungsberichte. Band 246). Vienna: Böhlaus, 1964.

- Hermann von Wissmann: Die Geschichte des Sabäerreiches und der Feldzug des Aelius Gallus. In: Hildegard Temporini: Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt. II. Principat. Ninth volume, First halfvolume. De Gruyter, Berlin/New York 1976, ISBN 3-11-006876-1, p. 308

- Pietsch, Dana, Peter Kuhn, Thomas Scholten, Ueli Brunner, Holger Hitgen, and Iris Gerlach. "Holocene Soils and Sediments around Ma’rib Oasis, Yemen, Further Sabaean Treasures." The Holocene 20.5 (2010): 785-99. Print.

- "Saba'", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013. Web. 27 September 2013.

External links

- "Queen of Sheba mystifies at the Bowers" – UC Irvine news article on Queen of Sheba exhibit at the Bowers Museum

- "A Dam at Marib" from the Saudi Aramco World online – March/April 1978

- Queen of Sheba Temple restored (2000, BBC)

- William Leo Hansberry, E. Harper Johnson, "Africa's Golden Past: Queen of Sheba's true identity confounds historical research", Ebony, April 1965, p. 136 — thorough discussion of previous scholars associating Biblical Sheba with Ethiopia.