Sabines

The Sabines (US: /ˈseɪbaɪnz/, SAY-bynes, UK: /ˈsæbaɪnz/, SAB-eyens;[1] Latin: Sabini; Italian: Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

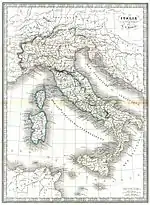

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The Sabines divided into two populations just after the founding of Rome, which is described by Roman legend. The division, however it came about, is not legendary. The population closer to Rome transplanted itself to the new city and united with the preexisting citizenry, beginning a new heritage that descended from the Sabines but was also Latinized. The second population remained a mountain tribal state, coming finally to war against Rome for its independence along with all the other Italic tribes. Afterwards, it became assimilated into the Roman Republic.

Etymology

The Sabines derived directly from the ancient Umbrians and belonged to the same ethnic group as the Samnites and the Sabelli, as attested by the common ethnonymous of Safineis (in ancient Greek σαφινείς) and by the toponyms safinim and safina (at the origin of the terms Samnium and Sabinum).[2] The Indo-European root *Saβeno or *Sabh evolved into the word Safen, which later became Safin. From Safinim, Sabinus, Sabellus and Samnis, an Indo-European root can be extracted, *sabh-, which becomes Sab- in Latino-Faliscan and Saf- in Osco-Umbrian: Sabini and *Safineis.[3]

At some point in prehistory, a population speaking a common language extended over both Samnium and Umbria. Salmon conjectures that it was common Italic and puts forward a date of 600 BC, after which the common language began to separate into dialects. This date does not necessarily correspond to any historical or archaeological evidence; developing a synthetic view of the ethnology of proto-historic Italy is an incomplete and ongoing task.[4]

Linguist Julius Pokorny carries the etymology somewhat further back. Conjecturing that the -a- was altered from an -o- during some prehistoric residence in Illyria, he derives the names from an o-grade extension *swo-bho- of an extended e-grade *swe-bho- of the possessive adjective, *s(e)we-, of the reflexive pronoun, *se-, "oneself" (the source of English self). The result is a set of Indo-European tribal names (if not the endonym of the Indo-Europeans): Germanic Suebi and Semnones, Suiones; Celtic Senones; Slavic Serbs and Sorbs; Italic Sabelli, Sabini, etc., as well as a large number of kinship terms.[5]

Language

| Sabine | |

|---|---|

| lingua Sabina | |

Statue of Semo Sancus from his shrine on the Quirinal | |

| Pronunciation | [saˈbiːna] |

| Native to | Sabina (Sabinum) |

| Region | Central Italy |

| Ethnicity | Sabines |

| Extinct | Only traces of vocabulary, mainly from Marcus Terentius Varro, 1st century BC |

| Latin alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | sbv |

sbv | |

| Glottolog | sabi1245 |

The linguistic landscape of Central Italy at the beginning of Roman expansion | |

| |

There is little record of the Sabine language; however, there are some glosses by ancient commentators, and one or two inscriptions have been tentatively identified as Sabine. There are also personal names in use on Latin inscriptions from the Sabine country, but these are given in Latin form. Robert Seymour Conway, in his Italic Dialects, gives approximately 100 words which vary from being well-attested as Sabine to being possibly of Sabine origin. In addition to these he cites place names derived from the Sabine, sometimes giving attempts at reconstructions of the Sabine form.[6] Based on all the evidence, the Linguist List tentatively classifies Sabine as a member of the Umbrian group of Italic languages of the Indo-European family.

Historical geography

Latin-speakers called the Sabines' original territory, straddling the modern regions of Lazio, Umbria, and Abruzzo, Sabinum. To this day, it bears the ancient tribe's name in the Italian form of Sabina. Within the modern region of Lazio (or Latium), Sabina constitutes a sub-region, situated north-east of Rome, around Rieti.

History

Origin and early history

The Sabines settled in Sabinum, around the tenth century BC, founding the cities of Reate, Trebula Mutuesca and Cures Sabini.[7][8] Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentions the Sabines in relation to the Aborigines, from whom they allegedly stole their capital Lista, with a surprise war action starting from Amiternum.[9] Ancient historians debated the specific origins of the Sabines. According to Strabo the Sabines, after a long war with the Umbrians, migrated to the land of the Opici, following the ancient Italic rite of the Ver Sacrum. The Sabines then drove out the Opici and encamped in that region.[10] Zenodotus of Troezen claimed that the Sabines were originally Umbrians that changed their name after being driven from the Reatine territory by the Pelasgians. Porcius Cato argued that the Sabines were a populace named after Sabus, the son of Sancus (a divinity of the area sometimes called Jupiter Fidius).[11] In another account mentioned in Dionysius's work, a group of Lacedaemonians fled Sparta since they regarded the laws of Lycurgus as too severe. In Italy, they founded the Spartan colony of Foronia (near the Pomentine plains) and some from that colony settled among the Sabines. According to the account, the Sabine habits of belligerence (aggressive or warlike behavior) and frugality (prudence in avoiding waste) were known to have derived from the Spartans.[12] Plutarch also mentions, in the Life of Numa Pompilius, "Sabines, who declare themselves to be a colony of the Lacedaemonians". Plutarch also wrote that the Pythagoras of Sparta, who was Olympic victor in the foot-race, helped Numa arrange the government of the city and many Spartan customs introduced by him to the Numa and the people.[13]

At Rome

Legend of the Sabine women

Legend says that the Romans abducted Sabine women to populate the newly built Rome. The resultant war ended only by the women throwing themselves and their children between the armies of their fathers and their husbands. The Rape of the Sabine Women became a common motif in art; the women ending the war is a less frequent but still reappearing motif.

According to Livy, after the conflict, the Sabine and Roman states merged, and the Sabine king Titus Tatius jointly ruled Rome with Romulus until Tatius' death five years later. Three new centuries of Equites were introduced at Rome, including one named Tatienses, after the Sabine king.

A variation of the story is recounted in the pseudepigraphal Sefer haYashar (see Jasher 17:1–15).

Traditions

Tradition suggests that the population of the early Roman kingdom was the result of a union of Sabines and others. Some of the gentes of the Roman republic were proud of their Sabine heritage, such as the Claudia gens, assuming Sabinus as a cognomen or agnomen. Some specifically Sabine deities and cults were known at Rome: Semo Sancus and Quirinus, and at least one area of the town, the Quirinale, where the temples to those latter deities were located, had once been a Sabine centre. The extravagant claims of Varro and Cicero that augury, divination by dreams and the worship of Minerva and Mars originated with the Sabines are disputable, as they were general Italic and Latin customs, as well as Etruscan, even though they were espoused by Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome and a Sabine.[14]

Religion

Sabine gods

- Angitia

- Diana[lower-alpha 1]

- Feronia[lower-alpha 1]

- Fortuna[lower-alpha 1]

- Fons[lower-alpha 1]

- Fides[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 1][16]

- Flora[lower-alpha 1]

- Herentas (equivalent of Venus)[17]

- the Lares (guardian deities)[lower-alpha 1]

- Larunda[lower-alpha 1]

- Lucina[lower-alpha 1]

- Luna[lower-alpha 1]

- Mamers[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 1]

- Mefitis

- Minerva[lower-alpha 1]

- the Novensides[18][lower-alpha 1] (council of thunder gods)

- Ops[lower-alpha 1]

- Pales[lower-alpha 1]

- Quirinus[lower-alpha 1]

- Sabus

- Salus[lower-alpha 1]

- Sancus

- Saturn[lower-alpha 1]

- Sol[lower-alpha 1]

- Soranus[lower-alpha 4]

- Strenia

- Summanus[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 1]

- Terminus[lower-alpha 1]

- Vacuna

- Vediovis[lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 1]

- Vortumnus[lower-alpha 1]

- Vitula

- Vulcan[lower-alpha 1]

Many of these deities were shared with the Etruscan religion, and were also adopted into the derivative Samnite and ancient Roman religion. Roman author Varro, who was himself of Sabine origin, gives a list of Sabine gods who were adopted by the Romans.[15] Elsewhere, Varro claims Sol Indiges – who had a sacred grove at Lavinium – as Sabine but at the same time equates him with Apollo.[19][20] Of those listed, he writes, "several names have their roots in both languages, as trees that grow on a property line creep into both fields. Saturn, for instance, can be said to have another origin here, and so too Diana."[lower-alpha 6]

Varro makes various claims for Sabine origins throughout his works, some more plausible than others, and his list should not be taken at face value.[21] But the importance of the Sabines in the early cultural formation of Rome is evidenced, for instance, by the bride abduction of the Sabine women by Romulus's men, and in the Sabine ethnicity of Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome, to whom are attributed many of Rome's religious and legal institutions.[22] Varro, however, says that the altars to most of these gods were established at Rome by King Tatius as the result of a vow (votum).[lower-alpha 7]

State

During the expansion of ancient Rome, there were a series of conflicts with the Sabines. Manius Curius Dentatus conquered the Sabines in 290 BC. The citizenship without the right of suffrage was given to the Sabines in the same year.[23] The right of suffrage was granted to the Sabines in 268 BC.[24]

Prominent Sabines

Gentes of Sabine origin

- Aemilia gens – Patrician

- Aurelia gens

- Calpurnia gens

- Calvisia gens

- Claudia gens – Patrician

- Curtia gens – Patrician

- Flavia gens

- Ligaria (gens)

- Marcia gens – Patrician

- Minatia (gens)

- Oppia gens – Patrician

- Opsia gens

- Ostoria gens

- Pantuleia (gens)

- Petronia gens

- Pinaria gens

- Pompilia gens

- Pomponia gens

- Poppaea gens

- Quirinia gens

- Rania gens

- Rubellia gens

- Sabinia gens

- Safinia gens

- Sallustia gens

- Saturia gens

- Sertoria gens

- Sicinia gens

- Tarpeia gens – Patrician

- Tineia gens

- Titia gens

- Valeria gens – Patrician

Romans of Sabine ancestry

- Titus Tatius, legendary King of the Sabines

- Numa Pompilius, legendary King of Rome

- Ancus Marcius, legendary King of Rome

- Quintus Sertorius, republican general

- Attius Clausus, founder of the Roman Claudia gens

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Roman writer

- Marcus Terentius Varro, Roman scholar

- Vespasian, Roman emperor and founder of the Flavian dynasty

Gallery

%252C_VII-VI_secolo_ac_ca.jpg.webp) Grave goods 7th-6th century BC

Grave goods 7th-6th century BC%252C_810-700_ac_ca.%252C_pettorale_in_bronzo_e_ambra.jpg.webp) Bronze and amber jewellery, c. 800-700 BC

Bronze and amber jewellery, c. 800-700 BC%252C_810-700_ac_ca.%252C_collana_a_8_fili.jpg.webp) Jewellery, c. 800-700 BC

Jewellery, c. 800-700 BC%252C_810-700_ac_ca.%252C_collana_con_pendenti_a_occhiali_e_fibula.jpg.webp) Ornaments, c. 800-700 BC

Ornaments, c. 800-700 BC%252C_810-700_ac_ca.%252C_fibula_a_disco_con_arco_foliato.jpg.webp) Ornaments, c. 800-700 BC

Ornaments, c. 800-700 BC%252C_810-700_ac_ca.%252C_pendagli_a_spirale_in_bronzo.jpg.webp) Bronze ornaments, c. 800-700 BC

Bronze ornaments, c. 800-700 BC

See also

| Library resources about Sabines |

Notes and references

Notes

- Later adopted into ancient Roman religion.[15]

- For Fides, see also Semo Sancus or Dius Fidius.

- God of war, with thunder attributes.

- God of underworld fire, with thunder attributes.

- God of darkness, with thunder attributes.

- Latin: e quis nonnulla nomina in utraque lingua habent radices, ut arbores quae in confinio natae in utroque agro serpunt: potest enim Saturnus hic de alia causa esse dictus atque in Sabinis, et sic Diana.

- Tatius is said by Varro to have dedicated altars to "Ops, Flora, Vediovis, and Saturn; to Sol, Luna, Vulcan, and Summanus; and likewise to Larunda, Terminus, Quirinus, Vortumnus, the Lares, Diana, and Lucina."

References

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Ambrosoli, Solone (1966). Rivista Italiana di NVMISMATICA e scienze affini (PDF) (in Italian). Pavia: Tipografia popolare. p. 70.

- Salmon 1967, p. 30.

- Salmon 1967, pp. 29–30.

- Pokorny 1959, pp. 882–884.

- Conway, Robert Seymour (1897). The Italic Dialects Edited with a Grammar and Glossary. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 351–369.

- "I Sabini e l'agricoltura: origine, storia, leggende, pastorizia, coltivazioni". Un Mondo Ecosostenibile (in Italian). 2021-02-20. Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- Riposati, Benedetto (1985). Convegno di studio: Preistoria, storia e civiltà dei Sabini (in Italian). Centro di studi varroniani.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. "Book I.14". Roman Antiquities.

Twenty-four stades from the afore-mentioned city stood Lista, the mother-city of the Aborigines, which at a still earlier time the Sabines had captured by a surprise attack, having set out against it from Amiternum by night.

- Strabo, Geography, book 5, 7 BCE, p. 250, Alexandria,

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. "Book II.49". Roman Antiquities.

But Zenodotus of Troezen, a...historian, relates that the Umbrians, a native race, first dwelt in the Reatine territory, as it is called, and that, being driven from there by the Pelasgians, they came into the country which they now inhabit and changing their name with their place of habitation, from Umbrians were called Sabines. But Porcius Cato says that the Sabine race received its name from Sabus, the son of Sancus, a divinity of that country, and that this Sancus was by some called Jupiter Fidius.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. "Book II.49". Roman Antiquities.

There is also another account given of the Sabines in the native histories, to the effect that a colony of Lacedaemonians settled among them at the time when Lycurgus, being guardian to his nephew Eunomus, gave his laws to Sparta. For the story goes that some of the Spartans, disliking the severity of his laws and separating from the rest, quit the city entirely, and after being borne through a vast stretch of sea, made a vow to the gods to settle in the first land they should reach; for a longing came upon them for any land whatsoever. At last they made that part of Italy which lies near the Pomentine plains and they called the place where they first landed Foronia, in memory of their being borne through the sea, and built a temple to the goddess Foronia, to whom they had addressed their vows; this goddess, by the alteration of one letter, they now call Feronia. And some of them, setting out from thence, settled among the Sabines. It is for this reason, they say, that many of the habits of the Sabines are Spartan, particularly their fondness for war and their frugality and a severity in all the actions of their lives. But this is enough about the Sabine race.

- Plutarch. "1". Numa.

Pythagoras, the Spartan, who was Olympic victor in the foot-race for the sixteenth Olympiad (in the third year of which Numa was made king), and that in his wanderings about Italy he made the acquaintance of Numa, and helped him arrange the government of the city, whence it came about that many Spartan customs were mingled with the Roman, as Pythagoras taught them to Numa. And at all events, Numa was of Sabine descent, and the Sabines will have it that they were colonists from Lacedaemon. Chronology, however, is hard to fix, and especially that which is based upon the names of victors in the Olympic games, the list of which is said to have been published at a late period by Hippias of Elis, who had no fully authoritative basis for his work. I shall therefore begin at a convenient point, and relate the noteworthy facts which I have found in the life of Numa.

- Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1857). "Sabini". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. Vol. II Iabadius – Zymethus. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Varro, De Lingua Latina 5.74

- Woodard, Roger D. Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman cult. p 184.

- Scheid, John (2016-03-07). "Venus". Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6730.

- Or Novensiles: the spelling -d- for -l- is characteristic of the Sabine language

- Varro. De lingua latina. 5.68.

- Rehak, Paul (2006). Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the northern Campus Martius. University of Wisconsin Press. p 94.

- Clark, Anna. (2007). Divine Qualities: Cult and community in republican Rome. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp 37–38;

Dench, Emma. (2005). Romulus' Asylum: Roman Identities from the Age of Alexander to the Age of Hadrian. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp 317–318. - Fowler, W.W. (1922). The Religious Experience of the Roman People. London, UK. p 108.

- Velleius Paterculus 1.14.6

- Velleius Paterculus 1.14.7

Sources

Ancient

- Ovid, Fasti (Book III, 167–258)

- Ovid, Ars Amatoria (Book I, 102)

- Livy, Ab urbe condita (Book I, 9–14)

- Cicero, De Republica (Book II, 12–14)

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives (Romulus, 14–20)

- Juvenal, Satires (Book III, 81–85)

- Maras, Daniele F.; Michetti, Laura Maria; Smith, Christopher J.; Tassi Scandone, Elena (2023). Fontes antiqui Sabinorum. I Sabini e la Sabina nelle fonti letteraie greche e latine. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 9788891327437.

Modern

- Donaldson, John William (1860). "Chapter IV: The Sabello-Oscan Language". Varronianus: a critical and historical introduction to the ethnography of ancient Italy and the philological study of the Latin language. London: John W. Parker and Son.

- Salmon, ET (1967). Samnium and the Samnites. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Pokorny, Julius (2005) [1959]. Indogermanisches etymologisches Woerterbuch. Leiden: Leiden University Indo-European Etymological Dictiopnary (IEED) Project. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27.

Further reading

- Brown, Robert. "Livy's Sabine Women and the Ideal of Concordia." Transactions of the American Philological Association 125 (1995): 291–319. doi:10.2307/284357.

- MacLachlan, Bonnie. Women In Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.