Sasol

Sasol Limited is an integrated energy and chemical company based in Sandton, South Africa. The company was formed in 1950 in Sasolburg, South Africa, and built on processes that German chemists and engineers first developed in the early 1900s (see coal liquefaction). Today, Sasol develops and commercializes technologies, including synthetic fuel technologies, and produces different liquid fuels, chemicals, coal tar, and electricity.[1]

| |

| Sasol | |

| Type | Public |

| NYSE: SSL JSE: SOL | |

| Industry | Oil and gas Chemical Coal tar |

| Predecessor | Suid-Afrikaanse Steenkool-, OLie- en Gasmaatskappy |

| Founded | 1950 |

| Headquarters | , South Africa |

Key people | Fleetwood Grobler (current CEO 2019) Bongani Nqwababa and Stephen Cornell (prior joint CEOs) |

| Revenue | $12.26 billion (2020) |

| $(7.15) billion (2020) | |

| $(5.867) billion (2020) | |

Number of employees | 30,100 |

| Website | www |

Sasol is listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE: SOL) and the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE: SSL). Major shareholders include the South African Government Employees Pension Fund,[2] Industrial Development Corporation[3] of South Africa Limited (IDC), Allan Gray Investment Counsel,[4] Coronation Fund Managers, Ninety One,[5] and others.[6] Sasol employs 30,100 people worldwide and has operations in 33 countries.[7] It is the largest corporate taxpayer in South Africa and the seventh-largest coal mining company in the world.[8]

History

The incorporation of Sasol

South Africa has large deposits of coal, which had low commercial value due to its high fly ash content. If this coal could be used to produce synthetic oil, petrol, and diesel fuel, it perhaps would have significant benefit to South Africa. In the 1920s, South African scientists started looking at the possibility of using coal as a source of liquid fuels. This work was pioneered by P. N. Lategan, working for the Transvaal Coal Owners Association. He completed his doctoral thesis from the Imperial College of Science in London on The Low-Temperature Carbonisation of South African Coal. In 1927, a white paper from the government was issued describing various oil-from-coal processes being used overseas and their potential for South Africa. In the 1930s, a young scientist named Etienne Rousseau obtained a Master of Science from the University of Stellenbosch. His thesis was entitled "The Sulfur Content of Coals and Oil Shales". Rousseau became Sasol's first managing director. After World War II, Anglovaal bought the rights to a method of using the Fischer–Tropsch process patented by M. W. Kellogg Limited, and in 1950, Sasol was formally incorporated as the South African Coal, Oil, and Gas Corporation (from the Afrikaans of which the present name is derived: Suid-Afrikaanse Steenkool-, Olie- en Gas Maatskappy), a state-owned company. Commissioning of the Sasol 1 site for the production of synfuels started in 1954. Construction of the Sasol 2 site was completed in 1980, with the Sasol 3 site coming on stream in 1982. The Zevenfontein farm house served as Sasol's first offices and is still in existence today.[9][10]

Coal mining

To support the required economies of scale for coal-to-liquids (CTL) process to be economical and competitive with crude oil, all stages of the operations, from coal mining to the Fischer–Tropsch process and product work up must be run with great efficiency. Due to the complexity of the Lurgi gasifers used, the quality of the coal was paramount. The initial annual output from the Sigma underground mine in Sasolburg was two million tons. Annual coal production from this mine peaked in 1991 at 7.4 million tons.[9] Today, most of the gasifiers in Sasolburg have been replaced with autothermal reformers that feed natural gas piped from Mozambique. Natural gas generates about 40–60% less carbon dioxide for the same energy produced as coal, thus is significantly more environmentally friendly. Gas-to-liquids technology converts natural gas, predominantly methane to liquid fuels.[9][10] Today, Sasol mines more than 40 million tons (Mt)[11] of saleable coal a year, mostly gasification feedstock for Sasol Synfuels in Secunda. Sasol Mining also exports some 2.8 Mt of coal a year. This amounts to roughly 22% of all the coal mined in South Africa. Underground mining operations continue in the Secunda area (Bosjesspruit, Brandspruit, Middelbult, Syferfontein, and Twistdraai collieries) and Sigma: Mooikraal colliery near Sasolburg. As some of these mines are nearing the end of their useful lives, a R14bn mine replacement program has been undertaken. The first of the new mines is the R3.4bn Thubelisha shaft, which will eventually be an operation delivering more than 8M tons/annum (mtpa) of coal over 25 years. The Impumelelo mine, which will replace the Brandspruit operation, is set for first production in 2015. It will be ramped up to produce 8.5 mtpa, and can later be upgraded to supplying some 10.5 mtpa. This coal will be used exclusively by the Sasol Synfuels plant. An underground extension of the Middelbult mine is also on the cards, with the main shaft and incline shaft being replaced by the Shondoni shaft. The first coal from the new complex was expected to be delivered in 2015.[12]

The Secunda collieries form the world's largest underground coal operations.[13]

In conjunction with the continuous improvement in the Fischer–Tropsch process and catalyst, significant developments were also made in mining technology. Coal mining at Sasol from the early days has been characterised by innovation. Sasol Mining mainly uses the room and pillar method of mining with a continuous miner. Sasol successfully used the longwall mining method from 1967 to 1987. Today, Sasol is one of the leaders in coal-mining technology and was the first to develop in-seam drilling from the surface using a directional drilling methodology. This has been developed into an effective exploration tool.[14] Working with Fifth Dimension, Sasol developed a virtual reality technology to help train continuous miner operators in a 3D environment in which various scenarios can be simulated, including sound, dust and other signs of movement.[15] This has recently been expanded to include shuttle car, roof-bolting, and load-haul dumper simulators.

Fischer–Tropsch reactor technology

The initial reactors from Kellogg and Lurgi gasifiers were tricky and expensive to operate. The original reactor design in 1955 was a circulating fluidised bed reactor (CFBR) with a capacity of about 1,500 barrels per day. Sasol improved these reactors to eventually yield about 6,500 barrels per day. The CFBR design involves moving the whole catalyst bed around the reactor, which is energy intensive and not efficient as most of the catalyst is not in the reaction zone. Sasol then developed fixed fluidized bed (FFB) reactors in which the catalyst particles were held in a fixed reaction zone. This resulted in a significant increase in reactor capacities. For example, the first FFB reactors commercialised in 1990 (5 m diameter) had a capacity of about 3,000 barrels per day, while the design in 2000 (10.7 m diameter) had a capacity of 20,000 barrels per day. Further advancements in reactor engineering have resulted on the development and commercialisation of Sasol Slurry Phase Distillate (SSPD) reactors which are the cornerstone of Sasol's first-of-a-kind GTL plant in Qatar.[9][10]

From fuels to chemicals

The fuel price is directly linked to the oil price, so is subject to potentially large fluctuations. With Sasol only producing fuels, this meant that its profitability was largely governed by external macroeconomic forces over which it had no control. How could Sasol be less susceptible to the oil price? The answer was right in front of them, in the treasure chest of chemicals co-produced in the Fischer–Tropsch process. Chemicals have a higher value per ton of product than fuels.

In the 1960s ammonia, styrene, and butadiene became the first chemical intermediates sold by Sasol. The ammonia was then used to make fertilizers. By 1964, Sasol was a major player in the nitrogenous fertilizer market. This product range was further extended in the 1980s to include both phosphate- and potassium-based fertilizers. Sasol now sells an extensive range of fertilizers and explosives to local and international markets, and is a world leader in its low-density ammonium nitrate technology.[16]

With the extraction of chemicals from its Fischer–Tropsch product slate coupled with downstream functionalization and on-purpose chemical production facilities, Sasol moved from being just a South African fuels company to become an international integrated energy and chemicals company with over 200 chemical products being sold worldwide. Some of the main products produced are diesel, petrol (gasoline), naphtha, kerosene (jet fuel), liquid petroleum gas (LPG), olefins, alcohols, polymers, solvents, surfactants (detergent alcohols and oil-field chemicals), co-monomers, ammonia, methanol, various phenolics, sulphur, illuminating paraffin, bitumen, acrylates, and fuel oil. These products are used in the production process of numerous everyday products made worldwide and benefit the lives of millions of people around the world. They include hot-melt adhesives, car products, microchip coatings, printing ink, household and industrial paints, mobile phones, circuit boards, transport fuels, compact discs, medical lasers, sun creams, perfumes and plastic bottles.[17]

In South Africa, the chemical businesses are integrated in the Fischer–Tropsch value chain. Outside South Africa, the company operates chemical businesses based on backward integration into feedstock and/or competitive market positions for example in Europe, Asia, and the United States.[17]

Greenhouse gas emissions

Sasol's Secunda CTL plant is as of 2020 the world's largest single emitter of greenhouse gas, at 56.5 million tonnes CO2 a year.[18]

Air Liquide acquired the 42,000 tons/day oxygen production in 2020, with plans for 900 MW power plants to reduce CO2 emissions.

According to independent researchers, Secunda "produces without doubt the most polluting liquid fuels in the world", said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst for the Centre for Energy Research and Clean Air, an independent research body. "The most alarming part is that Sasol is delaying and opposing South Africa's new air pollutant emissions standards that would more than halve the health impacts of industrial emissions."[18]

Operations

Sasol has exploration, development, production, marketing and sales operations in 31 countries across the world, including Southern Africa, the rest of Africa, the Americas, Europe, the Middle East (West Asia), Russia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania.[19]

The Sasol group structure is organised into two upstream business units, three regional operating hubs and four customer-facing strategic business units.[7]

Operating business units

Operating Business Units comprise the mining division and exploration and production of oil and gas activities, focused on feedstock supply.[20]

Sasol Mining operates six coal mines that supply feed-stock for Secunda (Sasol Synfuels) and Sasolburg (Sasolburg Operations) complexes in South Africa. While the coal supplied to Sasol Synfuels is mainly used as gasification feedstock, some is used to generate electricity. The coal supplied to the Sasolburg Operations is used to generate electricity and steam. Coal is also exported from the Twistdraai Export Plant to international power generation customers.

Sasol Exploration and Production International (SEPI) develops and manages the group's upstream interests in oil and gas exploration and production in Mozambique, South Africa, Canada, Gabon, and Australia.[21]

Regional operating hubs

These include operations in Southern Africa, North America and Eurasia.[22]

The Southern African Operations business cluster is responsible for Sasol's entire Southern Africa operations portfolio, which comprises all downstream operations and related infrastructure in the region. This combined operational portfolio has simplified and consolidated responsibilities relating to the company's operating facilities in Secunda, which are divided into a synthetic fuels and chemicals component, Sasolburg, Natref, Sasol's joint-venture inland refinery with TotalEnergies, and Satellite Operations, a consolidation of all Sasol's operating activities outside of Secunda and Sasolburg.[23]

The International Operations business cluster is responsible for Sasol's international operations in Eurasia and North America, which include its US mega-projects in Lake Charles, Louisiana.[24]

Strategic business units

Energy business

- Southern Africa Energy

- International Energy

The energy business manages the marketing and sales of all oil, gas and electricity products in Southern Africa, which have been consolidated under a single umbrella. In addition, this cluster oversees Sasol's international GTL (gas to liquids) ventures in Qatar, Nigeria and Uzbekistan.[25]

Chemical business

- Base Chemicals

- Performance Chemicals

The global chemicals business includes the marketing and sales of all chemical products, both in southern Africa and internationally. The chemicals business is divided into two niche groupings; Base Chemicals, where its fertilisers, polymers and solvents products lie, and performance chemicals, comprising key products which include surfactants, surfactant intermediates, fatty alcohols, linear alkyl benzene (LAB), short-chain linear alpha olefins, ethylene, petrolatum, paraffin waxes, synthetic waxes, cresylic acids, high-quality carbon solutions as well as high-purity and ultra-high-purity alumina and a speciality gases sub-division.[26]

In South Africa, the chemical businesses are integrated into the Fischer–Tropsch value chain. Outside South Africa, the chemical businesses are operated based on backward integration into feedstock and/or competitive market positions.

Group functions

Group Technology manages the research and development, technology innovation and management, engineering services and capital project management portfolios. Group Technology includes Research and Technology (R&T), Engineering and Project Services and Capital Projects.[27]

Major projects

United States

Sasol has granted final approval for a US$11 billion ethane cracker and derivatives plant near Westlake and the community of Mossville, both across the Calcasieu River from Lake Charles, Louisiana, and is the largest foreign investment in the history of the State of Louisiana. It was stated "Once commissioned, this world-scale petrochemicals complex will roughly triple the company's chemical production capacity in the United States, enabling Sasol to further strengthen its position in a growing global chemicals market. The U.S. Gulf Coast's robust infrastructure for transporting and storing abundant, low-cost ethane was a key driver in the decision to invest in America". The ethane cracker will also be supported by six chemical manufacturing plants.[28][29][30][31][32]

By January 2015 construction was in full swing. At peak the project will create 5000 construction and 1200 permanent jobs and cost $11 billion to $14 billion.[33]

Qatar

The Oryx GTL plant in Qatar is a joint venture between Sasol and QatarEnergy, launched in 2007. The more than 32,000 barrels per day (5,100 m3/d) plant produces a combination of GTL diesel, GTL naphtha and liquid petroleum gas.[34][35]

Uzbekistan

The proposed Uzbekistan GTL project is a partnership between Sasol, Uzbekneftegaz and Petronas.[36][37][38] Sasol reconsidered its involvement in March 2016

Mozambique

Sasol is developing a 140 MW gas-fired electricity generation plant in partnership with power utility EDM.[39] This gas project came into operation in 2004, and is a joint venture agreement between Sasol Petroleum International, Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos (ENH), and the International Finance Corporation.

Technology

Natref Refinery

Sasol is also involved in conventional oil refinery. Incorporated on 8 December 1967, construction started on the Natref refinery in 1968 and commissioned in Sasolburg in 1971.[40]: 166 [41]: 75 It was built as a joint venture between the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), National Iranian Oil Company and Compagnie Fransçaise de Petroles (Total) with financing by the Rembrandt Group, Volkskas and SA Mutual.[40]: 166 By 1979, prior to the Iranian Revolution, the refinery was receiving seventy percent of its oil from Iran and National Iranian Oil Company owned 17.5 percent of the facility.[42] Oil was piped 800 km from Durban via Richards Bay to the refinery.[42] The refinery is now a joint venture between Sasol Ltd and Total South Africa (Pty) Ltd. Sasol has a 63,64 percent interest in Natref and Total South Africa a 36,36 percent shareholding.[43] The refining capacity of Natref to 108,500 barrels per day. Natref is one of the only inland refineries in South Africa.[40]: 166 It was designed to get the most out of crude oil. The refinery uses the bottoms upgrading refining process using medium gravity crude oil and is capable of producing 70% more white product than coastal refineries that have to rely on heavy fuel oil. Some of the products produced from the refinery are diesel, petrol, jet fuel, LPG, illuminating paraffin, bitumen and sulfur. Natref has been certified in terms of the ISO 14001 Environmental Management System.[44][45]

Controversies

In 2009 Sasol agreed to pay an administrative penalty of R188 million as part of a settlement agreement with the Competition Commission of South Africa for alleged price fixing, in which a competitor alleged that Sasol was abusing its dominance in the markets for fertilisers by charging excessive prices for certain products. Sasol won an appeal on the case and will not be paying the settlement anymore.[46]

Sasol also had to pay a €318 million fine to the European Commission (EC) in 2008, which is about R3.7 billion, for participating in a paraffin wax cartel. Despite its indication that it would appeal the fine amount, the full amount had to be paid to the EC within three months of the fine being issued.[47][48]

Sasol has been levied with a R1.2bn tax provision by the Tax Court on 30 June 2017 on the back of its international crude oil purchases between 2005 and 2012. In its 2017 financial results announced on 21 August 2017, the chemical conglomerate agreed upon footing the R1.2bn tax liability. If the court's interpretation is implemented for the following two years – 2013 and 2014 – Sasol Oil's crude purchases could result in a further tax exposure of R11.6bn, thus summing up a total tax figure up to R12.8bn.[49]

Sasol has been in the spotlight since 2019 for their "culture of fear" which caused the cost overruns at their Lake Charles facility. It was Sasol's own chairman, Mandla Gantsho, who highlighted the "culture of fear" as one of the central reasons for the company's Lake Charles cost over-runs, as it had prevented bad news from about its Lake Charles project from flowing up the management chains of the organization. The "culture of fear" which undermined the transparent reporting of problems. Essentially Sasol management silenced bad news by of using fear as a method to control employees from speaking up on irregularities. These Sasol Lake Charles employees being essentially whistleblowers by definition. The Sasol "culture of fear" debacle resulted in the Sasol joint CEO's resigning on the 28th of October 2019 in an attempt to restore trust in the company, and replaced by Fleetwood Grobler as CEO of Sasol. Sasol's "culture of fear" caused significant losses to its shareholders, and as a result a class action lawsuit was initiated against Sasol by its U.S. investors, claiming that Sasol deliberately understated the cost of its Louisiana plant project. Sasol agreed to pay $24 million to settle the class action lawsuit brought by U.S. investors. Sasol has stated publicly that their actions of silencing whistle-blowers through a culture of fear and thus keeping bad news from being sent up the chain to shareholders has "negatively impacted Sasol's overall reputation, and led to a serious erosion of confidence in the leadership of the company and weakened the company financially".[50][51][52][53]

Criminally charged for unlawfully and knowingly dismissing a whistleblower

Sasol has unlawfully dismissed a whistleblower who exposed unlawful pollution and has been criminally charged for his unlawful dismissal. Ian Erasmus has started blowing the whistle on Sasol's unlawful disposal of hazardous waste internally in 2015 with no action by Sasol to stop these actions, and has subsequently disclosed his evidence to the SAHRC and DFFE in 2019, which resulted in the first environmental pollution criminal charges in Sasol's 73-year history. Sasol's published its first-ever whistleblower policy in June 2020, a month before the Whistleblower Ian Erasmus was unlawfully dismissed from Sasol in July 2020. On their website Sasol states that it encourages all stakeholders who have dealings with Sasol to "speak up when others do not on any actual or suspected unethical conduct without fear of adverse consequences",[54] yet Sasol has been criminally charged for "unlawfully and knowingly dismissing a whistleblower" within the company a month after publishing its first-ever Whistleblower Policy. Sasol's website states that "Sasol strictly prohibit any form of retaliation, intimidation, harassment or victimization against a reporter who in good faith makes a report or raises a concern that he or she reasonably believes to be a violation of Sasol's Code of Conduct. Retaliation against employees is prohibited even if their reports or concerns are proven unfounded by an investigation". Sasol has publicly denied all allegations and insisted that the whistleblower Ian Erasmus, who was an employee with Sasol for more than 15 years, has been lying about his allegations on Sasol's incorrect disposal of hazardous waste which may have ended up in the Vaal River since February 2019.

The action which Sasol has taken to dismiss this whistleblower who reported unlawful disposal of hazardous waste from the Benfield units on the Sasol Secunda facility, is unlawful according to various South African laws and published legal acts. In particular, the National Environmental Management Act of South Africa (NEMA), specifically section 31.4/5/6/8, whereas the NEMA act states that "no person is civilly or criminally liable or may be dismissed, disciplined, prejudiced or harassed on account of having disclosed information in good faith of an environmental risk". Sasol has also contravened the Companies Act 71 of 2008 section 159, the Labour Relations Act 66 of 1995 section 186.d, and especially the Protected Disclosures Act 26 of 2000, regarding its unlawful dismissal of the whistleblower Ian Erasmus for his disclosures to the South African Human Rights Commission in 2019 and the Department of Forestry Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) since 2019 till now. The South African Environmental Minister, Barbara Creecy, was questioned on the 1st of April 2022, by the South African Parliamentary member, Dave Bryant, regarding the disclosures made by Ian Erasmus regarding his allegations on Sasol's unlawful disposal of hazardous waste which may end up in the Vaal River. Minister Barbara Creecy subsequently acknowledged to South African Parliament[55] in writing that the claims of Ian Erasmus regarding the malfunctioning Benfield Valves which caused serious pollution, were verified and triggered a criminal investigation into these claims. Criminal investigation under the case number "Secunda CAS 19/06/2021". Sasol has been criminally charged by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) on the 27th of July 2022, with various environmental pollution charges, and also for unlawfully and knowingly dismissing the whistleblower Ian Erasmus.

Sasol has been criminally charged on the evidence provided to the DFFE by Ian Erasmus. Sasol's way of informing their shareholders of these historic criminal charges was only a small one-sentence line on page 8 of its 2022 shareholder prospectus regarding this very important criminal charge. It is the first time in Sasol's 73-year history that the company has been criminally charged for environmental pollution. The criminal case against Sasol is currently sub judice end the next court date is set for the 14th of July 2023 at the Secunda Magistrates Court.[56][57][58][59][60][55][61][62][63]

David Constable was at the helm of Sasol as CEO when the deal was sealed in 2014 with Fluor, Constable's previous employer, as the main contractor to build Sasol's mega project in Lake Charles. David Constable had worked for Fluor since 1982 to 2011, and left Fluor for the position of CEO at Sasol in 2011, only to leave Sasol in 2016 and return to Fluor as its CEO. Between his position as CEO of Sasol and his position of CEO at Fluor David only served as a board member for the three companies ABB, RIO Tinto and Cerberus Capital. Constable was appointed as CEO of Fluor just after the controversial cost overruns of Sasol's Lake Charles facility started to dig into Sasol's share price and reputation. It was under Constable's leadership that Sasol was signed into troublesome contract with his former employer, Fluor. David Constable also oversaw Sasol's 2014 "Project Phoenix" where a Sasol considerably reduced its work force.[64]

Sasol's documented environmental pollution

According to industry experts, Sasol's Secunda facility is facing becoming a stranded asset in a world that is becoming more environmentally and green energy conscious. It is a documented fact that Sasol's Secunda facility in South Africa is the largest single-point greenhouse gas emitter on the planet. At 56.5 million tons of greenhouse gases a year, Secunda's emissions exceed the individual totals of more than 100 countries. A hazy polluted atmosphere is a daily sight in and around the town of Secunda.[65][66]

In May 2014 Sasol instituted legal proceedings against the Minister of Environmental Affairs and the National Air Quality Officer in South Africa, to set aside a number of air quality standards or "minimum emission standards" applicable to Sasol's industrial activities. These standards require significant reductions in the harmful pollutants that the operations of Sasol emit. Sasol also has had to upgrade its facilities to comply with the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy new regulations regarding Petroleum Products Specifications and Standards; this has forced domestic refineries in South Africa to decide whether they will be upgraded to meet these new regulations.[67][68][69]

The Department of Environmental Affairs fervently resisted Sasol's litigation and defended the emission standards, which were first published in 2010. In December 2014, the National Air Quality Officer filed a strongly worded answering affidavit, accusing Sasol of using "tactics" and "misdirection" "to hide their delay in bringing this review application and the associated delay in having to invest in emission abatement technology towards compliance with the minimum emission standards to combat pollution". The National Air Quality Officer also said that "what [Sasol] is in fact seeking is a judicial license to continue with air pollution from their existing plants unabated over the next few years".[69][68]

In an open letter to the Minister of Environmental Affairs in October 2014, 11 environmental NGOs and community-based organizations urged the Minister not to allow Sasol's litigation to bring undue pressure to bear on the Department of Environmental Affairs. The letter's signatories reminded the Minister that Sasol had been a key player in the five-year-long multi-stakeholder process convened to determine appropriate minimum emission standards for big industry, and that the standards had already been weakened due to industry lobbying of the department.[68][69]

After Sasol was granted rolling postponements to comply with the "minimum emission standards", Sasol withdrew its controversial litigation. And for more than a decade Sasol has avoided compliance with air pollution standards and have delayed any meaningful reductions of greenhouse gases.[70][71]

Sasol faced off against environmental activists during its 2022 Annual General Meeting with shareholders on 2 December 2022, regarding Sasol's slacking off on its self-imposed targets to cut emissions by 30% by 2030, and reach net zero by 2050. Fleetwood Grobler, CEO, admitted that Sasol may not be moving fast with its climate change objectives and asked activists and investors to be patient. Grobler stated that Sasol cannot sacrifice profit to achieve its de-carbonisation goals. Sasol also faced multiple questions regarding the criminal charges related to the unlawful disposal of hazardous waste as well as questions regarding their dismissal of the whistleblower who exposed the unlawful disposal of hazardous waste at its Secunda facility.[72][73][74]

The "Deadly Air case"

Environmental rights organizations, GroundWork and Vukani Environmental Justice Movement in Action, filed a lawsuit against the South African government in 2019 over its failure to take meaningful action against big air polluters Eskom and Sasol who "violate the constitutional right to a safe and healthy environment" as is enshrined in the South African Constitution section 24. The South African High Court found that the DFFE minister, Barbara Creecy, has a legal duty to prescribe regulations under section 20 of the National Environmental Management Air Quality Act to implement and enforce the "Highveld Priority Area (HPA) air quality management plan".[75][76][77]

On the 18th of March 2022, the presiding Judge Colleen Collis stated in her judgment "it is declared that the minister has unreasonably delayed in preparing and initiating regulations to give effect to the Highveld plan (HPA)". The court has directed Creecy, within 12 months of the order, to "prepare, initiate, and prescribe" regulations in terms of section 20 to implement and enforce the plan. The HPA is home to 12 of Eskom's coal-fired power stations, and Sasol's coal-to-liquid fuels refinery, situated in Secunda, all supplied by numerous coal mining operations. Judge Colleen Collis stated it was commonly accepted that the air pollution in the HPA was responsible for premature deaths, decreased lung function, deterioration of the lungs and heart, and the development of diseases such as asthma, emphysema, bronchitis, TB and cancer, adding: "It is also acknowledged that children and the elderly, especially with existing conditions such as asthma, are particularly vulnerable to the high concentrations of air pollution in the HPA."[78]

The minister of the DFFE has applied for leave to appeal the "deadly air case" judgment on 13 March 2023 and has been granted leave to appeal by Judge Collis on the 18th of March 2023. It remains to be seen what actions if any the minister of Environment will take to ensure Sasol's compliance to minimum emissions standards.[79][80]

Sasol's application for postponement denied by South African National Air Quality Officer (NAQO)

The National Air Quality Officer (NAQO) has denied Sasol's June 2022 application to be exempt from complying to the MES, Minimum Emissions Standard. Sasol was itself a participant in the establishing of the MES, but has been requesting rolling postponements since 2015 instead of complying with these MES requirements and stipulations. Sasol will now have to install relevant equipment to comply with the MES, or shut down the relevant equipment. Sasol has indicated that it would appeal this decision by the National Air Quality Officer (NAQO) by the 1st of August 2023.[81][82][83]

Sasol has been slammed by the National Air Quality Officer (NAQO) for its failure to reduce pollution. Sasol's application for exemption has not been granted because Sasol has failed to demonstrate any real effort to curb emissions of the toxin sulfur dioxide (SO2). Sasol was granted a one-time exemption in 2015 after Sasol threatened the government with litigation. Patience Gwaze, the National Air Quality Officer (NAQO), referred to the one-time postponement already granted to Sasol in 2015 and said "to permit such indulgence into perpetuity would defeat the objective" of the MES limits. Gwaze also stated that "Sasol is also in breach of the agreed upon MES limits for NOx (nitrogen oxides) as well as particulate matter emissions and had been granted postponements for those pollutants".

Barbara Creecy stated "that herself and her predecessors were constrained by laws that mean air pollution enforcement is largely in the hands of Municipalities". Air pollution enforcement of Sasol's Secunda facility falls under the control Govan Mbeki Municipality, which has itself been implicated in corruption claims by political parties as well as its local citizens.[84][85][86]

Sulfur Dioxide is known to cause heart attacks, strokes, various respiratory diseases, several different cardiovascular diseases (especially children) and acid rain among others.[87][88][89]

Sasol spokesperson, Alex Anderson, released a public statement saying "that Sasol complied with most emission limits and has spent R7 billion (South African Rand) curbing pollution over the last five years". Sasol's NET operating profit for 2022 stands at $7.29 Billion(US), which equates to around R122 Billion (South African Rand) NET operating profit for the one year, 2022.[90][91]

Sasol had applied to have its emissions of sulfur dioxide measured in total tonnage emitted over a period, instead of adhering to the concentration emitted of the toxin, which is the industry standard. Under Sasol's requested method of monitoring of its sulfur dioxide emissions, it means that a very dangerous amount of sulfur dioxide can be released at any given short period, just as long as the total emitted SO2 over a period stays below the limit.[92]

According to Professor (professor emeritus in chemical engineering) Eugene Cairncross, "Sasol wanted an average" with intermittent periods of very concentrated emissions of Sulfur Dioxide. Professor Cairncross stated that "your lungs does not operate in that way, you breathe every few seconds. What they (Sasol) had proposed represented a significant slackening of the limit".[92]

Sasol stated in their sustainability report that they emitted at their Secunda facility, 137 300 tonnes of sulfur dioxides and 49.2 million tons of climate warming carbon dioxide (CO2).[93]

Barbara Creecy has told Bernard Klingenberg, executive vice president of energy operations at Sasol, "that Sasol wouldn't be allowed to postpone installation of abatement equipment past March 2025". Barbara Creecy herself has been ordered by the High Court Of South Africa to "take meaningful action against Sasol's air pollution".[94][95][96][97] Sasol's spokesperson declined to comment at the time. Sasol has to date (2023) not been criminally charged with any air pollution charges by the South African Government.[98]

Poisoned water

In November 2015 Sasol was served with a summons for a lawsuit demanding R150 million in damages. This claim was made by a land owner, Derrick Erasmus who owned Templemore Trading 69, who owned land directly West from Sasol's Charlie 5 gate and directly North of Sasol's coarse ash heaps and Fine ash dams. The Klipspruit also runs through Templemore's land after it has passed through Sasol's property.[99]

A cattle farmer, Chris Skosana, who had rented Templemore's property to graze his cattle on, has lost 50 head of cattle from 2009 to 2014 due to poisoned water on this property. A report was issued by Sasol to Templemore stating "the water quality of the two dams renders them unsuitable for livestock watering" and the "water poses a risk to the health of the cattle". Sasol started supplying fresh water to Chris Skosana for his cattle on this land, but Sasol's lawyers threatened to cut the fresh water supply, so the farmer withdrew a court application against Sasol.

Templemore confronted Sasol about a suspicious white residue on the property, after which Sasol admitted that it was forced to release contaminated water into the water system running through Templemore's property and into the Kleinspruit due to a crack that had developed in one of Sasol's pollution dams. Test results from 2011 and 2013 from the cattle's drinking dams contained high levels of selenium, molybdenum, sulphates and fluoride. Sasol then commissioned a second "specialist toxicologist" who found the water to be safe for cattle to consume.

But the land owner, Templemore, maintained that the pollution was not from one incident in December 2013, and had its own water and soil samples laboratory tested. The tests showed elevated levels of a wide range of metals, including Mercury, Copper, Manganese, Vanadium and Lead. Sasol's waste permits allowed it to dump 8820 tons of toxic waste into a Black Products dam every day. According to Sasol's spokesperson Alex Anderson, this Black Products dam was never lined, and was only "underplayed with clay soils" which limits the amount of waste leaking from them, which confirms that this dam does leak into the groundwater. One of the criminal charges Sasol is currently facing concerns Sasol's unlawful disposal of hazardous waste containing Vanadium into this Kleinspruit River, and another criminal charge Sasol is currently facing is for the unlawful rehabilitation of this Black Products dam nearby the property on which these cattle were grazing between 2009 and 2014.[100]

Dead fish

On 31 January 2022, Sasol sent out an internal communication concerning dead fish that were found in the Klipsruit River adjacent to the Sasol Secunda facility during Sasol's release of contaminated stormwater from their API dams into the river. Immediate area impacted was the Klipspruit River at Sasol's RESM7 in river analyzing station. This is the same Klipsruit River concerning the criminal charges against Sasol for another matter. Sasol's statement regarding the incident was "Water quality measurements at RESM7 indicated elevated concentrations compared to the limits as stipulated in the Water Use License (WUL) for the Klipspruit. The aquatic assessment concluded that the impact may have been sudden and that the fish died within a short period of time. Rapid changes in the water course can negatively impact aquatic life. Intermittent controlled releases of process water (process water includes Sasol's Cooling Water) and stormwater occurred at Secunda Operations before (approximately 8 hours) the dead fish was observed. These are governed in terms of a directive received from the DWS. In this regard we wish to point out that no dead fish or other aquatic impacts were observed when subsequent controlled releases occurred. Intermittent controlled releases of process water and storm water occurred at Secunda Operations before (approximately 8 hours) the dead fish was observed. These are governed in terms of a directive received from the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS). In this regard, we wish to point out that no dead fish or other aquatic impacts were observed when subsequent controlled releases occurred. The storm water in question is assumed to be contaminated since it includes run-off water from within the plant area of Sasol Secunda Operations", yet it was still released into a fresh water source.[101][102]

Sasol spokesperson Matebello Motloung said the sustainability of the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS) was crucial to managing long-term water-supply risks, "hence we have a vested interest in the responsible management of the Integrated Vaal River System". Motloung said intermittent controlled releases of process water and stormwater occurred at Secunda operations before the dead fish was observed.

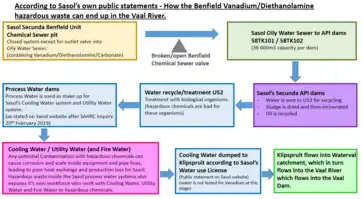

Sasol has confirmed the process flow route of the Benfield Chemical Sewer system to their API dams through its own official public media releases. Sasol confirms that the Benfield hazardous waste on which the current criminal charges are based, can indeed end up in the Klipsruit River unchecked via the process flow route for their API Dams. Sasol stated in their official media release of the 8th of April 2021, that "the bunded Benfield area is connected to a chemical sewer drain which, in turn, is a closed system with a valve leading to/draining into the factory's oily water system. Benfield is designed for its effluents to feed into the oily water system of the plant, via the chemical sewer drain. The oily water sewer system drains into the API oily water dams. All the water in the API oily water dams is treated and recycled for eventual use as process water in our Secunda Operations" These API dams are the facility's catchment dams for stormwater, as well as for hydrocarbon polluted water via the "Oily Water Sewer system" of the Sasol Secunda facility. Sasol also confirmed with their official public statement of the 21st of February 2019, that the Sasol Secunda facility regularly releases Cooling Water into the Klipspruit which flows into the Vaal River. Sasol stated that "our Secunda Operations lawfully discharges treated effluent (cooling water and treated domestic wastewater) and stormwater into the Waterval catchment in accordance with the provisions of our Water Use License (WUL) issued by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS)". See the attached diagram below depicting the process flows that Sasol's official statements explain. The Minister of Environment, Barbara Creecy, has also confirmed to her answer to South African Parliament that the "Benfield Chemical Sewer" valves were indeed broken and replaced a few weeks prior as alleged by the whistleblower, which resulted in the criminal investigation into the allegations against Sasol by the DFFE starting in 2019 and resulted in criminal charges against Sasol in 2022.[103][104][55]

The minister of Environment has already officially confirmed to South African Parliament[55] that these "Benfield Chemical Sewer valves" had been replaced just prior to their investigation starting in 2019. Sasol previously confirmed in their official public media release of process water, which includes Cooling Water, into the Klipsruit River according to their Water Use License - "our Secunda Operations lawfully discharges treated effluent (cooling water and treated domestic wastewater) and storm water into the Waterval catchment (which flows into the Vaal River) in accordance with the provisions of our Water Use License (WUL) issued by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS). The whistleblower alleges the Benfield hazardous waste was disposed of into Sasol's API dams. Sasol confirmed via its own public media releases that the unlawful hazardous waste disposal can end up unchecked in the Klipsruit as a result of Sasol's action of regularly disposing of Cooling Water into the Klipsruit".

Sasol admits to struggling to comply with their waste disposal licenses

Sasol has publicly stated that they are struggling to comply with their stringent waste discharge license issued to Sasol by the DWS. Sasol's environmental affairs manager Bob Kleynjan said "our discharge compliance [has] been good... we may have had challenges here and there, but we have been improving how we discharge our waste as per the stringent licence regulations from the sanitation department". Despite Sasol's public admittance to non-compliance of their waste discharge license, the company has vehemently denied the allegations regarding their unlawful disposal of hazardous waste from its Secunda Facility which can reach the Vaal River.

Sasol's Sustainable water manager, Martin Ginster, stated that frequent amendments to waste management licences also hindered compliance. Sasol has agreed to work with the Department of Water and Sanitation to research a better tool for the discharge license so that there was a better understanding by Sasol and also better compliance by Sasol in disposing its waste.[105][106]

Criminal charges for environmental pollution - Vaal River

On Wednesday the 27th of July 2022, Sasol was criminally charged by the South African National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), for unlawful disposal of hazardous chemicals in the Vaal River system in a "manner that was likely to cause pollution of harm to human health and well-being". It is the first time in Sasol's 73-year history that it has been criminally charged for environmental pollution. The charges is set out on a 12-page charge sheet, which lists six counts in contravention of the National Environmental Management - Waste Act at its Secunda Synfuels Operations in Mpumalanga, South Africa.

The DFFE opened a criminal case against Sasol with the South African Police under the case number CAS19/06/2021. The summons was issued on 27 July 2022 by the Secunda Magistrates court and the National Prosecuting Authority has laid criminal charges against Sasol for environmental pollution, including a criminal charge for unlawfully and knowingly dismissing a whistleblower, Ian Erasmus, for exposing pollution at its Sasol Secunda facility.[107][108][109][110][111]

The charges against Sasol is:

- The unauthorized disposal of waste;

- Unlawful prejudice an/or dismissal of a whistleblower who in good faith disclosed evidence of a potential environmental risk;

- Disposal of waste in a manner that is likely to cause pollution;

- Two separate charges of Commencing activities in the absence of an environmental authorization;

- Unlawful, negligent disposition/discharge of contaminated water into a water resource

Facing fines for environmental pollution

In the ongoing criminal case regarding environmental pollution as well as unlawfully dismissing a whistleblower, Sasol faces multiple fines as set out below.

If convicted of the offence of "unauthorized disposal of waste", Sasol is liable to a fine not exceeding R10-million, or to no longer than a 10-year imprisonment term, or both.

If convicted of the offence of "unlawfully dismissing a whistleblower", it is liable to a fine not exceeding R5-million or to imprisonment not exceeding five years "and in the case of a second or subsequent conviction", to a fine not exceeding R10-million or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding 10 years.

If convicted of the offence of "disposal that is likely to cause pollution", Sasol is liable to a fine not exceeding R10-million, or to no longer than a 10-year imprisonment term, or both.

If convicted of either of the two charges regarding the offence of "commencing with a listed activity without an environmental authorization", Sasol is liable to a fine not exceeding R10-million, or to no longer than a 10-year imprisonment term, or both for each of these two charges.

If convicted of the offence of "unlawful, negligent disposition/discharge of contaminated water into a water resource, Sasol is liable to a fine not exceeding R10-million, or to no longer than a 10-year imprisonment term, or both.[112][113]

The trial for the criminal charges

Trial started on the 20th of September 2022 in the Secunda Magistrate's Court under Case Number: 477/2022. The case is ongoing, and the next trial date is set for the 7th of August 2023.

For the State : Mr Mahasha (NPA)

For the defendant (Sasol) : Mr Mike Helens.

Sasol has chosen Mike Helens as their senior counsel in the criminal case regarding the environmental pollution. Mike Helens has gained a name for himself in the public eye for his choice of notorious clients which include among others ex South African president Jacob Zuma, who is still on the hook for corruption charges, as well as the notorious Gupta's of South Africa, who have been exposed on multiple counts of fraud and corruption linked with Jacob Zuma.[114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121]

References

- "Company Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "GEPF - Home". www.gepf.gov.za. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Home - Industrial Development Corporation". www.idc.co.za. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Allan Gray | Investment Company | Investment Management". www.allangray.co.za. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Home | Global | Investec Asset Management". www.investecassetmanagement.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Major Shareholders | Sasol". Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "About Sasol". Archived from the original on 15 November 2017.

- Donnelly, Lynley (4 July 2008). "Sasol the tax cow". Mail & Guardian. Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "mind over matter". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

- Sasol Facts 12/13 Booklet

- "Products | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Sasol Secunda & Sasolburg Underground Mining Operations". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Business Overview – Sasol Mining | Sasol". Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- "Mining Weekly - New coal-exploration technology". www.miningweekly.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Author, System. "New coal-exploration technology". Mining Weekly. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "fertilizer". Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- "Overview | Sasol". Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- "The World's Biggest Emitter of Greenhouse Gases". Bloomberg.com. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- "Global presence". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- "Operating Business Units Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Sasol Exploration & Production International | Overview". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Overview | Sasol". www.sasol.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Sasol and State of Louisiana Join Forces".

- "Sasol and Louisiana". The Wall Street Journal. 3 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- Krauss, Clifford (3 December 2012). "Sasol Plans First Gas-To-Liquids Plant in US". New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012.

- "Sasol Spend on Louisiana Plant". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Sasol Announces Final Investment Decision on World-Scale Ethane Cracker and Derivatives Complex in Louisiana". Archived from the original on 11 November 2014.

- Sayre, Katherine (29 August 2014). "Sasol clears permitting hurdle". Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Sasol and Qatar". The Wall Street Journal. 3 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- "Sasol Reports Rise in SA Output". Mining Weekly. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- "Sasol eyes Uzbek GTL project". Brand South Africa. 9 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Petronas signs Uzbek GTL pact". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Malaysia's Petronas in Uzbekistan oil-production deal". Reuters. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Mozambique Natural Gas Project" (PDF). SASOL. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2013.

- Fine, Ben; Rustomjee, Zavareh (1996). The Political Economy of South Africa: From Minerals-energy Complex to Industrialisation. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 9781850652588.

- Technology, United States Congress House Committee on Science and (1980). Oversight of energy development in Africa and the Middle East: report to the Committee on Science and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, Ninety-sixth Congress, second session. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa, Issues 2064-2073. United States. Joint Publications Research Service. 1979.

- "Natref to spend R600m". Fin24. 17 May 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "Natref Refinery". www.total.co.za. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Natref Sasolburg Refinery - A Barrel Full". abarrelfull.wikidot.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Sasol Nitro Settlement and Competition Law Compliance Review". 20 May 2009. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- "Competition-related fines dent 2009 profit figures". 23 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- "Sasol faces R3,7bn price fixing penalty". 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- "Sasol prepares for tax battle". Fin24. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "SENS Article". www.sharedata.co.za. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "S.Africa's Sasol agrees $24 mln settlement in U.S class action suit". Reuters. 1 September 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "Sasol seeks to use leadership 'reset' to rebuild trust in wake of damning LCCP review". www.engineeringnews.co.za. 28 October 2019.

- "UPDATE 2-Sasol joint CEOs step down after review of tarnished U.S. project". Reuters. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "WHISTLEBLOWING |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Question number 1310 Parliament asking Minister of Environment South Africa about allegations against Sasol by whistleblower Ian Erasmus" (PDF). www.dffe.gov.za. 1 April 2022.

- "Millions in fines if Sasol is found guilty of polluting the Vaal River system". The Mail & Guardian. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "WHISTLEBLOWING |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "'It's absolutely terrifying to be a whistleblower in Sasol'". The Mail & Guardian. 27 March 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- Anderson, Alex (12 December 2021). "LETTER TO THE EDITOR: Sasol denies industrial pollution allegations made by whistle-blower". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- https://web.facebook.com/Encee.van.Huyssteen (30 August 2022). "Sasol facing environmental charges - The Bulletin". Retrieved 11 June 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - "Protected Disclosures Act 26 of 2000(of South Africa)" (PDF). www.justice.gov.za.

- "National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 | South African Government". www.gov.za. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "Companies Act 71 of 2008 | South African Government". www.gov.za. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- "Jobs impact still uncertain as Sasol moves to finalise streamlined structure". www.engineeringnews.co.za.

- Joubert, Leonie (12 August 2019). "OUR BURNING PLANET: ANALYSIS: Pension funds at risk as tide turns against carbon-polluting industries". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "The World's Biggest Emitter of Greenhouse Gases". Bloomberg.com. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Retaining refining capacity could pose long term risks for South Africa". www.engineeringnews.co.za.

- Melissa (20 April 2015). "Joint media release: Sasol withdraws ill-conceived litigation against the State to set aside air quality standards". Centre for Environmental Rights. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Sasol Synfuels (Pty) Ltd and others v Minister of Environmental Affairs and another". Centre for Environmental Rights. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "DEA: Minister Edna Molewa welcomes SASOL decision to withdraw litigation against the government". www.polity.org.za.

- "So. Africa: Sasol abandons litigation challenging stricter air emission standards; includes company comments". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/Moneyweb (5 December 2022). "SASOL LIMITED – Results of Annual General Meeting of Sasol held on Friday, 2 December 2022 - SENS". Moneyweb. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - Reed, Ed (2 December 2022). "Sasol faces tough questions on transition at AGM". Energy Voice. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Steyn, Lisa. "Despite fiery criticism, Sasol investors once again give nod to its climate plans". Business. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Judge to rule after South Africa sued over Sasol, Eskom pollution". www.engineeringnews.co.za.

- https://www.facebook.com/Moneyweb (10 June 2019). "South Africa sued for Eskom, Sasol air pollution in coal belt". Moneyweb. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - Melissa (3 July 2019). "Government is being sued over Eskom, Sasol threat to the environment". Centre for Environmental Rights. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "High court slams Creecy for deadly air that breaches SA's Constitution". The Mail & Guardian. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Omarjee, Lameez. "Deadly Air case: Creecy granted leave to appeal". Business. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Deadly air pollution case back in court, 'residents' rights breached'". www.iol.co.za.

- "Update On The Application In Terms Of Clause 12A Of The Minimum Emission Standards In South Africa; Sasol To Appeal |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Sasol to appeal the rejection of its bid to be regulated on an alternative emission standard basis". IOL News.

- "Engineering News - Sasol to appeal latest MES application rejection". Engineering News. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "GOVAN MBEKI ON THE BRINK OF FINANCIAL RUIN". www.parliament.gov.za/.

- "DA approaches Hawks to investigate intensified corruption, fraud and maladministration in Govan Mbeki Municipality". Democratic Alliance - Mpumalanga. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "eMba residents demand to pay Eskom directly". Ridge Times. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Association, American Lung. "Sulfur Dioxide". www.lung.org. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Sulfur Dioxide Effects on Health - Air (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Government of Canada, Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (13 June 2023). "CCOHS: Sulfur Dioxide". www.ccohs.ca. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Sasol Gross Profit 2010-2022 | SSL". www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Financial Results | Financial Results". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- https://www.facebook.com/Moneyweb (14 July 2023). "Sasol slammed by SA's pollution regulator over lack of investment". Moneyweb. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - "Sustainability report 2021" (PDF). /www.sasol.com.

- Bloomberg. "Eskom, Sasol rebuffed, Creecy says as she fights pollution suit". Engineering News. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Bloomberg. "Eskom, Sasol rebuffed, Creecy says in pollution suit fight". City Press. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Deadly air case: Govt's appeal against ruling to take action on Sasol, Eskom to start". Business. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "Court orders clampdown on Sasol, Eskom pollution". /businesstech.co.za.

- "Emissions put Sasol in legal jeopardy". BusinessLIVE. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Comrie, Susan. "Poisoned water". City Press. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Stock farmer fights Sasol over pollution". News24. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Klipspruit stream contaminated near Sasol". www.thebulletin.co.za.

- "Dead fish found in stream near Sasol's Secunda plant". The Mail & Guardian. 11 April 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Sasol employee whistleblower testimony at HRC hearing on 20 February 2019 |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Sasol sets the record straight on alleged Vaal River pollution and its participation in the SAHRC investigation |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- Phakgadi, Pelane. "Vaal River pollution: 'There have been challenges to compliance', Sasol says". News24. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- SAHRC. "Vaal River pollution: 'There have been challenges to compliance', Sasol says". www.sahrc.org.za. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- https://web.facebook.com/Encee.van.Huyssteen (30 August 2022). "Sasol facing environmental charges - The Bulletin". Retrieved 17 June 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - "Sasol's statement on criminal charges pertaining to Secunda Operations environmental management |". www.sasol.com. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Sasol faces charges of water pollution in Secunda". Ridge Times. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Sasol in Secunda faces water pollution charges". Ridge Times. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Sasol in the dock for environmental degradation at Secunda, polluting the Vaal River". The Mail & Guardian. 26 August 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Millions in fines if Sasol is found guilty of polluting the Vaal River system". The Mail & Guardian. 26 September 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- https://web.facebook.com/Encee.van.Huyssteen (2 October 2022). "Environmental charges levelled against Sasol - The Bulletin". Retrieved 17 June 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); External link in|last= - "The phrase 'Gupta-linked' has no content in law — Trillian counsel". The Mail & Guardian. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Gupta lawyers take aim at NPA's advocate". South African Lawyer. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Zuma's former lawyers Mike Hellens and Dawie Joubert reportedly arrested in Namibia". TimesLIVE. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "High court tells Trillian: 'Pay back the Eskom money'". The Mail & Guardian. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Advocate may sue NPA over Breytenbach affair 'lies'". The Mail & Guardian. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "Lawyer questions motives around Breytenbach affair claims". The Mail & Guardian. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- "SA advocate in hot water in Swaziland". legalbrief.co.za. Archived from the original on 18 June 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- "Randburg court in stitches as Duduzane Zuma's lawyer shouts 'Mshini Wam'". IOL News.

External links

- Sasol Official website

- How Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa perfected one of the world's most exciting new fuel sources. Slate Magazine

- Google Maps view of Sasol's Secunda plant

- SciFest Africa, part of Sasol's investment in science education in South Africa

- Sasol suffers shareholder fury at AGM over e318m EU fine

- Activist shareholder turns the screws on Sasol

- Fury at Sasol's AGM over price-fixing fine

- Greenpeace Sues Sasol for Corporate Espionage – video report by Democracy Now!