Saxon Renaissance

The Saxon Renaissance (in German: Sächsische Renaissance) is a regional type of architecture from the Renaissance particularly in the area of the Electorate of Saxony on the middle Elbe. Influences that formed the style came primarily from Bohemia, Italy and Poland. There were Italian artist families involved by wandering around and roaming the Saxon cultural area in search of commissions. Thus ensured a mixture of styles as well as the own Saxon style development.

History

The most important forerunner of the Renaissance in Saxony was the Electoral Saxon master builder Arnold von Westfalen (ca. 1425-1481), who created the Albrechtsburg Castle in Meissen in the transition from late Gothic to Renaissance. Transitional forms of building décor can also be found at Hartenfels Castle in Torgau, Wurzen Castle, Hinterglauchau Castle in Glauchau and Heynitz Castle.

Decisive for the spread of the new architectural style, which originated in Italy and spread throughout Germany at the same time, was the Saxon ruling family of the Wettins, who had their own large buildings commissioned and, under Elector Maurice, also called Italian artists to Saxony. Well-known artists and builders who worked in Saxony were: Giovanni Maria Nosseni from Lugano, Hans von Dehn-Rothfelser, Benedetto Tola (* 1525 in Brescia/Italy; † 1572), Gabriel de Tola, Caspar Vogt von Wierandt, Hans Irmisch, Rochus zu Lynar, Carlo di Cesare del Palagio. Franz Maidburg erected the main altar of the town church of Annaberg in 1519 and initiated the Renaissance in Saxony. The Saxon master builders used the Renaissance style from about 1530 and exported it to northern Germany (Brandenburg, Mecklenburg).[2]

_-_DE.png.webp)

After the Wettin possessions were divided into an Ernestine and an Albertine line in 1485, Torgau developed next to Wittenberg into the preferred residence of the Ernestine electors. The Torgau Castle Hartenfels with its famous Wendelstein, which was significantly rebuilt by the middle of the 16th century, is one of the most important buildings of the early Renaissance in Germany. After the Wittenberg capitulation and the transition of Torgau to the Albertines, Elector Maurice initially continued the work on the castle. The permanent relocation of the residence to Dresden until the end of the 16th century largely saved Hartenfels Castle from later stylistic transformations, such as those experienced by the Dresden Residence Castle, which was considerably enlarged from 1548 until 1556. The facades of the Dresden Palace were richly decorated with sgraffiti and Maurice's brother and successor, Elector Augustus, who reigned from 1553 until 1586, completed the construction, which became a major work of the Saxon Renaissance. Later, however, the interior was rebuilt in baroque style after a fire and the outer facades were reworked in the neo-Renaissance style in the 19th century.

The territory of Saxony did not yet include the margravates of Upper and Lower Lusatia, which belonged to the Lands of the Bohemian crown and only fell to Saxony in 1635. Saxony also reached further north into the Fläming. At the beginning of the early Renaissance, the Wettin lands were fragmented. The Lutheran Reformation emanated from the Saxon Electorate, which was under Ernestine rule and had its centers of power in Wittenberg and Torgau, while the Reformation was not introduced until 1539 in the Albertine dominions adjoining to the south (mainly the Margravate of Meissen). After the end of the Schmalkaldic War in 1547, the Upper Saxon Meissen area formed a politically consolidated area.

The artistic and structural development was particularly encouraged by Elector Augustus, who ruled from 1553 until his death in 1586. His great interest in questions of construction and architecture is documented. His library contained many architectural pamphlets and model books of building elements. His main work is the enormous Augustusburg, built between 1568 and 1572. Nowhere else in Europe was an ideal geometric plan implemented so uniformly. The design of the original model could go back to August himself. He also completed the extensive conversion of the Dresden Residential Palace (1553-1556), which his brother Maurice had started. He let build Jägerhof (Dresden) and converted numerous older castles into hunting lodges, including Nossen, Grillenburg, Schwarzenberg and the new Gommern Castle. He had Annaburg Castle and Lichtenburg Castle built for his wife, and Dippoldiswalde and Freudenstein as official castles. His successor Christian I (1586–1591) continued his father's building activities. Above all, Nosseni's work caused the architectural style to spread in Saxony.

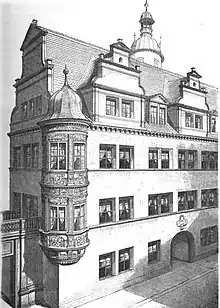

The style rubbed off on private building activity in urban centers. Wealthy citizens began to copy the resulting magnificent buildings in Dresden and Meissen and erected houses with arched portals , facades with square oriels above the ground floor, often attached in pairs. Further domestic stylistic elements of the Renaissance can be found on the ornaments of the front doors and the window frames. The wooden ceilings are magnificently designed. The way in which most of the town houses of this time were designed can be traced back to the influence of Dresden. In addition to the buildings, altars and grave slabs have also become the subject of the changed design in Saxony. In cities such as Meissen, Pirna, Freiberg, Görlitz, Zwickau, Torgau and Wittenberg there are still today numerous Renaissance town houses.

From 1656, Wolf Caspar von Klengel (1630–1691) became chief master builder (Oberlandbaumeister) in Saxony; under him the late Renaissance forms were transforming themselves bit by bit into the new Baroque style. As a “prelude”, Johann Georg Starcke built the Dresden Palais in the Great Garden for John George II from 1678, based on models from the French and Italian early Baroque. John George's grandson Augustus II the Strong, who was impressed by his grandfather's opulent court festivals, pushed the new architectural style forward with unprecedented energy from 1694 and thereby created the Dresden Baroque, which shaped an entire century and radiated far beyond national borders. The Renaissance gables of the Ortenburg Castle in Bautzen, which were not erected until 1698 according to plans by Martin Pötzsch, show how long the building traditions trained in the Renaissance continued to have an effect ; gables in a similar, even baroque-looking transitional style were already attached to Althörnitz Castle around 1660.

Spatial differentiation

In addition to the Saxon expression of the Renaissance styles, there are in the different parts of Germany some other distribution areas with specific expressions of this style.[3] These are:

- North German Renaissance region

- Renaissance in the Weser area

- Westphalian Renaissance region

- Rhenish Renaissance region

- Renaissance on the Main

- Renaissance in the Neckar region

- Renaissance region in the foothills of the Alps

In other countries, there are also different regional characteristics.

Architectural characteristics

Characteristic are the typical triangular gables on the wall dormers and tower structures (in the early period also round gables), plus a dominance of the colors white and gray as well as consistently plastered buildings without natural stone décor. Buildings from the time of the Saxon Renaissance can be found today in almost all areas that belonged to the House of Wettin at the time of the Renaissance, i.e. today in several states of Germany as Saxony, Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt (southern part) and Brandenburg (Lower Lusatia) as well as in adjacent foreign areas such as Poland and Bohemia.

On the other hand, master builders of the Weser Renaissance carried out the conversion of the old monastery into Leitzkau Castle near Magdeburg, whose facades and gables have natural stone décor and fan tips.

Works

The most striking and preserved large buildings of this time were above all castles and town halls, which can still be found in large numbers in their original state.

Selection of buildings of the Saxon Renaissance with the typical features:

Dresden Castle, Saxony

Dresden Castle, Saxony Hartenfels Castle in Torgau (Saxony)

Hartenfels Castle in Torgau (Saxony) Torgau Town Hall, Saxony

Torgau Town Hall, Saxony Old Town Hall (Leipzig), Saxony

Old Town Hall (Leipzig), Saxony Augustusburg Hunting Lodge, Saxony

Augustusburg Hunting Lodge, Saxony Town Hall in Pirna, Saxony

Town Hall in Pirna, Saxony Dessau Palace, Saxony-Anhalt

Dessau Palace, Saxony-Anhalt%252C_a_detail_of_the_Bernburg_castle%252C_image_3.jpg.webp) Bernburg Castle, Saxony-Anhalt

Bernburg Castle, Saxony-Anhalt Halle Cathedral in Halle, Saxony-Anhalt

Halle Cathedral in Halle, Saxony-Anhalt Town Hall in Wittenberg, Saxony-Anhalt

Town Hall in Wittenberg, Saxony-Anhalt Lutherhaus in Wittenberg, Saxony-Anhalt

Lutherhaus in Wittenberg, Saxony-Anhalt Townhall in Saalfeld, Thuringia

Townhall in Saalfeld, Thuringia Castle in Doberlug-Kirchhain, Brandenburg

Castle in Doberlug-Kirchhain, Brandenburg One of the Dornburg Castles at the river Saale in Thuringia

One of the Dornburg Castles at the river Saale in Thuringia Castle in Ranis, Thuringia

Castle in Ranis, Thuringia Zabeltitz Castle, Saxony

Zabeltitz Castle, Saxony Jägerhof Dresden, Saxony

Jägerhof Dresden, Saxony Lichtenburg Castle in Prettin, Saxony-Anhalt

Lichtenburg Castle in Prettin, Saxony-Anhalt Pretzsch Castle, Saxony-Anhalt

Pretzsch Castle, Saxony-Anhalt Annaburg Castle, Saxony-Anhalt

Annaburg Castle, Saxony-Anhalt Town hall of Bad Schmiedeberg, Saxony-Anhalt

Town hall of Bad Schmiedeberg, Saxony-Anhalt Hinterglauchau Castle, Saxony

Hinterglauchau Castle, Saxony Osterstein Castle (Zwickau), Saxony

Osterstein Castle (Zwickau), Saxony Heynitz Castle, Saxony

Heynitz Castle, Saxony Schönfeld Castle (Dresden), Saxony

Schönfeld Castle (Dresden), Saxony

References

- Sebastian Ringel, Leipzig! One Thousand Years of History, Leipzig 2015, ISBN 978-3-361-00710-9, p.41

- Wilhelm Lübke: Geschichte der deutschen Renaissance (Tome 3), p. 775, in German, translation of the title: History of the German Renaissance

- "The (..) fragmentation of the country (..) led to special territorial developments in architecture. A distinction is made between the Dutch-influenced Renaissance that arose in northern Germany and the architectural forms of the Weser area, and the central German Renaissance architecture from that of southern Germany. What they all had in common was an imaginative richness of form. The Italian models were seldom copied schematically, but new national building forms were found in connection with the rich late Gothic building traditions." Translation of a passage of this German book: Herbert Kürth / Aribert Kutschmar, Baustilfibel , Volk + Wissen, Berlin 1978, p. 137