Second Purim

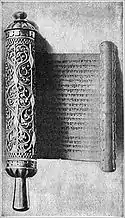

Second Purim (Hebrew: פורים שני, romanized: Purim Sheni), also called Purim Katan (Hebrew: פורים קטן, lit. 'Minor Purim'),[1][2][3] is a celebratory day uniquely observed by a Jewish community or individual family to commemorate the anniversary of its deliverance from destruction, catastrophe, or an antisemitic ruler or threat. Similar to the observance of the Jewish holiday of Purim, Second Purims were typically commemorated with the reading of a megillah (scroll) describing the events that led to the salvation, specially-composed prayers, a festive meal, and the giving of charity. In some cases, a fast day was held the day before. Second Purims were established by hundreds of communities in the Jewish diaspora and in the Land of Israel under foreign rule.[1] Most Second Purims are no longer observed.[1]

A Second Purim did not replace the regular Purim observed on 14 Adar (or 15 Adar, in Jerusalem and a few other cities), which all Jews are required by rabbinic law to observe.

Sources

A halakhic source for the custom of establishing a Second Purim is cited by the Chayei Adam on Orach Chayim 686:

Anyone to whom a miracle happened, or all the residents of a city, can ordain by mutual agreement or by censure upon themselves and all who come after them, to make that day a Purim. And it seems to me that the festive meal that they make to celebrate the miracle is a seudat mitzvah. (Sefer Chayei Adam, Hilkhot Megillah 155, ¶41)[4]

Date

The date of a Second Purim marked the anniversary of the day the community or individual was rescued from destruction, catastrophe, or an antisemitic ruler or threat.[1][5] Some Second Purims coincided with Jewish holidays, such as the Purim of Ancona, Italy, which fell on the second day of Sukkot, and the Purim of Carpentras, France, marking the community's rescue from a blood libel on the eighth day of Passover.[1] The Purim of Rhodes coincided with Purim day itself, when the local Jews were exonerated from a blood libel in 1840.[5][6]

Although days of celebration are typically not held during periods of mourning on the Jewish calendar, Second Purims were established during those times to commemorate the exact date of the salvation. For example, the Purim of Candea was celebrated on 18 Tammuz and the Purim of Ibrahim Pasha (in Hebron) was commemorated on 1 Av, even though these dates fall during The Three Weeks of national mourning for the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.[1]

Observances

The community or family celebrated its Second Purim with observances similar to those of the regular Purim.[1] These observances included some or all of the following:

- The writing and reading of a special megillah (scroll) retelling the events leading to the salvation.[1][5] In the Jewish communities of Castile, Saragossa, and Casablanca, the scroll was read in the synagogue using the traditional cantillation of the Scroll of Esther.[1]

- The composition and recital of special liturgical poems and prayers.[5][3] Some of these poems were written in the style of Al HaNissim ("On account of the miracles", the prayer recited on Purim and Hanukkah). These were recited during the Amidah and during the Grace After Meals on the Second Purim.[1] Some communities said the Hallel prayer during the morning service on their Second Purim, even though Hallel is not recited on Purim day.[1][7]

- A fast day on the day prior[3]

- The eating of a festive meal[3]

- The giving of charity to the poor.[1] Some communities also exchanged mishloach manot, the traditional food gifts to friends given on Purim day.[3]

- The cessation of business activities.[5][3]

Notable Second Purims

Purim Ancona (21 Tevet)

The Jewish community of Ancona, Italy, was noted for having four different communal Purims commemorating their salvation from potential disasters in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[6] The first of these was established on 29 December 1690 (21 Tevet), when strong earthquakes rattled the city.[5] On 15 Tishrei 1741, a fire threatened but did not destroy the synagogue. On 24 Adar 1775 the Jewish quarter was similarly spared from a fire. On 12 Shevat 1797 the Jewish population escaped rioting during a revolutionary war.[7] In each case, a communal fast day was held the day before the holiday and special prayers were said on both days.[5]

Purim of the Bandits (22 Elul)

Popularly known as Purim de los Ladrones (Purim of the Bandits), this celebration marked the deliverance of the Jewish population of Gumeldjina, a city near Adrianople, Ottoman Empire, from accusations of disloyalty. In 1786 the city was attacked by an estimated 5,000 mountain brigands. Though the governor managed to drive off the invaders, the Jews were accused of helping the bandits enter the city. The community went to great lengths to prove its innocence, and further disaster was averted.[5][8]

Purim Burghul (29 Tevet)

In 1795 the Jews of Tripoli, Libya, established Purim Burghul to celebrate the ouster of Ali Burghul Pasha Cezayrli, who usurped the throne and conducted a reign of terror against them from 30 July 1793 to 20 January 1795. The piyut, "Mi Kamokha" (Hebrew: מי כמוך, "Who is like You"), composed by Rabbi Abraham Khalfon, was read in the synagogue on the Shabbat preceding Purim Burghul.[9][10]

Purim Cairo (28 Adar)

In 1524 the governor of Egypt, Aḥmed Shaiṭan Pasha, arrested twelve of the Jewish leaders of Cairo, including Chief Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra, and demanded an exorbitant ransom. One day he threatened to murder all the Jews in Cairo after he had finished taking his bath. He was stabbed to death in the bathhouse by one of his junior officers and the massacre was averted.[5][2]

Purim Hebron (14 Tevet, 1 Av)

The Jewish community of Hebron has celebrated two historic Purims, both from the Ottoman period.[11] One is called Window Purim, or Purim Taka, in which the community was saved when a bag of money mysteriously appeared in a window, enabling them to pay off an extortion fee to the Ottoman Pasha.[12][13] The other is the Purim of Ibrahim Pasha (1 Av), in which the community was saved during a battle.[14][15]

Purim Narbonne (21 Adar)

In the heat of an argument between a Jew of Narbonne, France, and a Christian fisherman, the Jew struck the Christian and the latter died. Christian residents rioted in the Jewish quarter and stole the entire library belonging to Rabbi Meir ben Isaac. The governor fortuitously arrived on the scene with his troops and order was restored. Rabbi Meir received his library back and wrote a megillah commemorating the event.[5]

Purim Rhodes (14 Adar)

In 1840 Greeks who were in competition with Jews in the sponge trade on the island of Rhodes accused the Jewish community of murdering a child for ritual purposes. The Jews of Rhodes were jailed and tortured, though the child was later discovered alive on the island of Syra. The sultan, 'Abd al-Majid, deposed the local governor and issued a firman confirming the accusations were false. The date of the firman coincided with the date of Purim itself, and so the Jews of Rhodes celebrated a double holiday on that day. Special prayers and piyutim were recited in honor of Purim Rhodes, in addition to the usual Purim observances.[5]

Purim Saragossa (18 Shevat)

This holiday commemorated the downfall of a Jewish convert named Marcus, who informed the king that the Jews had removed the Torah scrolls from their cases when they brought them to a parade to honor the king in Saragossa, Spain. While the city's rabbis had instructed the Jews to do so, it impugned the king's honor, and the king called for the cases to be opened on the street the next day. That night, the gabbais of the city's twelve synagogues found out about the order and returned the scrolls to their cases. The next day, Marcus' malfeasance was exposed and the king ordered him to be put to death by hanging. It is uncertain whether this event took place in 1380 under Peter IV of Aragon or in 1420 under Alfonso V of Aragon. Purim Saragossa was celebrated by the descendants of the original Jewish community in synagogues in Constantinople, Magnesia, Smyrna, Salonica, and Jerusalem.[5]

Purim Sebastiano (1 Elul)

In 1578 Don Sebastian, king of Portugal, went to Morocco to join the Battle of the Three Kings at Alcazar-kebir. Sebastian was defeated by Sultan Moulay Abd-al-Malik and the Jews were saved from calamity.[5] According to a 2005 work, Purim Sebastiano (also called Purim de los Christianos and Purim de las Bombas) is still commemorated annually in Tangier, Tétouan, and Fez; the holiday incorporates the reading of a megillah, the recital of special hymns, and the giving of charity.[5][16]

Purim Tiberias (7 Elul and 4 Kislev)

The Jews of Tiberias established communal Purims on two dates in 1743 after Suleiman Pasha, governor of Damascus, laid siege to the city for 83 days. The governor lifted the siege on 27 August. While planning his next attack, he suddenly died. The Jews of Tiberias celebrated both the day the siege was lifted (7 Elul) and the day the governor died (4 Kislev) as Second Purims.[5][8]

Purim Vinz (20 Adar)

This communal Purim commemorates the persecution and expulsion of the Jewish population of the Frankfurter Judengasse during the Fettmilch Uprising in 1614 and their restoration to their homes on the order of the German emperor in 1616. The antisemitic leader of the uprising, Vincent Fettmilch, styled himself as the "New Haman" and propagated attacks on the Jewish community. In a final attack, the Jews were expelled and their property confiscated. Several months later, the German emperor ordered that Fettmilch be executed for the injustice; his beheaded and quartered corpse was hung on the gates of the city. Fettmilch's house was also razed, and an account of his crimes and punishment was engraved on a pillar in German and Latin at the site. The Frankfurt authorities welcomed the Jewish population back with military honors. A "Vincent Megillah" was composed in Hebrew and Yiddish by Rabbi Elhanah Ha'elen.[1]

Frankfurt natives Rabbi Nathan Adler (1741–1800) and Rabbi Moses Sofer (the Chasam Sofer, 1762–1839) both observed Purim Vinz even while living outside the city, though neither fasted on the day before the festival, as was done in Frankfurt itself.[6]

Purim of Rabbi Avraham Danzig (16 Kislev)

The family of Rabbi Avraham Danzig (the Chayei Adam) established their own Second Purim after an explosion of magnesium in a military camp near their home in Vilnius destroyed many houses and killed 31 residents in 1803.[1][5][7] Danzig and his family were also injured, but survived. The family commemorated this personal miracle by fasting during the day of 15 Kislev and holding a celebratory feast later that night (corresponding to 16 Kislev). Torah scholars were invited to the feast, psalms were read, and charity was distributed.[17] This Second Purim was also known as Pulverpurim ("Powder Purim") in Yiddish,[5][3]

Purim of Rabbi Yom Tov Lipman Heller (1 Adar)

In 1644,[5] Rabbi Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller of Kraków instructed his descendants to celebrate a Second Purim every 1 Adar to commemorate the end of his many troubles, including imprisonment on trumped-up charges.[18]

Purim Fürhang ('Curtain Purim') (22 Tevet)

Chanoch ben Moshe Altschul of Prague designated this annual celebration for his family to commemorate his release from prison in 1623. When damask curtains were stolen from the governor's palace in his absence, all the city's synagogues announced that anyone who had the stolen goods in his possession should turn them over to the gabbai. A certain Jew delivered the curtains to Altschul, then the gabbai of the Maisel Synagogue, claiming he had purchased them from two soldiers. The vice-governor demanded that the buyer be named and delivered to him for punishment, but Altschul was forbidden by synagogue bylaws to name receivers of stolen goods who had returned them voluntarily. Altschul was imprisoned and sentenced to death by hanging. He sought and received permission from the president of the synagogue to name the buyer, who was hung instead. Altschul was released from prison after the Jewish community paid a fine of 10,000 florins. Altschul wrote a scroll titled "Megillat Pur ha-Ḳela'im" ("Scroll of the Purim of the Curtains"), and obligated all his descendants to read it and eat a festive meal every year on 22 Tevet, the day of his release.[5]

Purim Povidl ('Plum Jam Purim') (10 Adar)

In 1731, David Brandeis of Jung-Bunzlau, Bohemia, established this familial Purim in commemoration of his personal deliverance. On 4 Shevat, the daughter of a Christian bookbinder purchased from Brandeis povidl (plum jam) which made her family ill; her father died a few days after eating it. The burgomaster of the city ordered the closure of Brandeis' store and imprisoned him, his wife, and son for selling poisonous food to Christians. Investigations by municipal authorities and the court of appeal in Prague revealed that the bookbinder had died of consumption and the charges were dismissed. Brandeis wrote a scroll which he called Shir HaMa'alot l'David ("A Song of Ascents to David"), to be read on 10 Adar, accompanied by a festive meal. Brandeis' descendants in the nineteenth century were still celebrating Purim Povidl.[5]

Second Purims observed by other groups

In Karaite Judaism, 1 Shevat is celebrated as a Second Purim; this was the day (year unknown) that a Karaite leader named Yerushalmi was freed from prison.[7]

Followers of Sabbatai Zvi established a Second Purim on 15 Kislev, honoring the day in 1648 that their leader declared himself the Jewish Messiah.[7]

References

- "When is Purim Observed?". Orthodox Union. 29 June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Megillath Esther, p. 38.

- Geller, Dr. Yaakov (2008). "פורים קטן: ימי פורים קהילתיים, מקומיים, ארציים ומשפחתיים" [Purim Katan: Communal, Local, National, and Familial Purims] (in Hebrew). Bar-Ilan University. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Sefer Chayei Adam" (PDF). daat.ac.il. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Deutsch, Gotthard; Franco, M.; Malter, Henry (2011). "Purims, Special". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Kaganoff, Rabbi Yirmiyohu (5 March 2015). "From Cairo to Frankfurt, Part II". rabbikaganoff.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- "Purims, Special". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Domnitch, Larry. "Special Purims". myjewishlearning.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Stewart 2006, p. 225.

- Hirschberg 1981, p. 154.

- "The Legend of the Window Purim and other Hebron Holiday Stories". the Jewish Community of Hebron. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Purim Hebron". www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Ben-Amos, Noy, and Frankel (2006). Folktales of the Jews. Volume 1, Tales from the Sephardic dispersion. Ben-Amos, Dan., Noy, Dov., Frankel, Ellen., Arkhiyon ha-sipur ha-ʻamami be-Yiśraʼel (Haifa, Israel) (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. p. 25. ISBN 0827608292. OCLC 649905156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Erev Purim 5776". www.sefaria.org.il. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "פורים של איברהים פחה" [Purim of Ibrahim Pasha]. www.hebron.co.il (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Zafrani 2005, p. 265.

- "Gunpowder Purim".

donate extra tzedakah (charity)

- "This Day in Jewish History: Adar". ou.org. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

Sources

- Greenblatt, Rachel L. (2014). To Tell Their Children: Jewish Communal Memory in Early Modern Prague. ISBN 9780804786027.

- Hirschberg, H. Z. (1981). A History of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time. Vol. II. Brill. p. 154. ISBN 9004062955.

- Megillath Esther. Feldheim Publishers. 1993. ISBN 158330164X.

- Stewart, John (2006). African States and Rulers (3rd ed.). McFarland & Company. p. 225. ISBN 0-7864-2562-8.

- Zafrani, Haim (2005). Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco. KTAV Publishing House. p. 265. ISBN 0881257486.