Cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

_at_sea_in_1985.jpg.webp)

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hundred years, has changed its meaning over time. During the Age of Sail, the term cruising referred to certain kinds of missions—independent scouting, commerce protection, or raiding—usually fulfilled by frigates or sloops-of-war, which functioned as the cruising warships of a fleet.

In the middle of the 19th century, cruiser came to be a classification of the ships intended for cruising distant waters, for commerce raiding, and for scouting for the battle fleet. Cruisers came in a wide variety of sizes, from the medium-sized protected cruiser to large armored cruisers that were nearly as big (although not as powerful or as well-armored) as a pre-dreadnought battleship.[1] With the advent of the dreadnought battleship before World War I, the armored cruiser evolved into a vessel of similar scale known as the battlecruiser. The very large battlecruisers of the World War I era that succeeded armored cruisers were now classified, along with dreadnought battleships, as capital ships.

By the early 20th century, after World War I, the direct successors to protected cruisers could be placed on a consistent scale of warship size, smaller than a battleship but larger than a destroyer. In 1922, the Washington Naval Treaty placed a formal limit on these cruisers, which were defined as warships of up to 10,000 tons displacement carrying guns no larger than 8 inches in calibre; whilst the 1930 London Naval Treaty created a divide of two cruiser types, heavy cruisers having 6.1 inches to 8 inch guns, while those with guns of 6.1 inches or less were light cruisers. Each type were limited in total and individual tonnage which shaped cruiser design until the collapse of the treaty system just prior to the start of World War II. Some variations on the Treaty cruiser design included the German Deutschland-class "pocket battleships", which had heavier armament at the expense of speed compared to standard heavy cruisers, and the American Alaska class, which was a scaled-up heavy cruiser design designated as a "cruiser-killer".

In the later 20th century, the obsolescence of the battleship left the cruiser as the largest and most powerful surface combatant ships (aircraft carriers not being considered surface combatants, as their attack capability comes from their air wings rather than on-board weapons). The role of the cruiser varied according to ship and navy, often including air defense and shore bombardment. During the Cold War the Soviet Navy's cruisers had heavy anti-ship missile armament designed to sink NATO carrier task-forces via saturation attack. The U.S. Navy built guided-missile cruisers upon destroyer-style hulls (some called "destroyer leaders" or "frigates" prior to the 1975 reclassification) primarily designed to provide air defense while often adding anti-submarine capabilities, being larger and having longer-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) than early Charles F. Adams guided-missile destroyers tasked with the short-range air defense role. By the end of the Cold War the line between cruisers and destroyers had blurred, with the Ticonderoga-class cruiser using the hull of the Spruance-class destroyer but receiving the cruiser designation due to their enhanced mission and combat systems.

As of 2023, only three countries operate active duty vessels formally classed as cruisers: the United States, Russia and Italy. These cruisers are primarily armed with guided missiles, with the exceptions of the aircraft cruisers Admiral Kuznetsov and Giuseppe Garibaldi.[2][3][4][5] BAP Almirante Grau was the last gun cruiser in service, serving with the Peruvian Navy until 2017.

Nevertheless, other classes in addition to the above may be considered cruisers due to differing classification systems. The US/NATO system includes the Type 055 from China[6] and the Kirov and Slava from Russia.[7] International Institute for Strategic Studies' "The Military Balance" defines a cruiser as a surface combatant displacing at least 9750 tonnes; with respect to vessels in service as of the early 2020s it includes the Type 055, the Sejong the Great from South Korea, the Atago and Maya from Japan and the Ticonderoga and Zumwalt from the US.[8]

Early history

The term "cruiser" or "cruizer"[9] was first commonly used in the 17th century to refer to an independent warship. "Cruiser" meant the purpose or mission of a ship, rather than a category of vessel. However, the term was nonetheless used to mean a smaller, faster warship suitable for such a role. In the 17th century, the ship of the line was generally too large, inflexible, and expensive to be dispatched on long-range missions (for instance, to the Americas), and too strategically important to be put at risk of fouling and foundering by continual patrol duties.[10]

The Dutch navy was noted for its cruisers in the 17th century, while the Royal Navy—and later French and Spanish navies—subsequently caught up in terms of their numbers and deployment. The British Cruiser and Convoy Acts were an attempt by mercantile interests in Parliament to focus the Navy on commerce defence and raiding with cruisers, rather than the more scarce and expensive ships of the line.[11] During the 18th century the frigate became the preeminent type of cruiser. A frigate was a small, fast, long range, lightly armed (single gun-deck) ship used for scouting, carrying dispatches, and disrupting enemy trade. The other principal type of cruiser was the sloop, but many other miscellaneous types of ship were used as well.

Steam cruisers

During the 19th century, navies began to use steam power for their fleets. The 1840s saw the construction of experimental steam-powered frigates and sloops. By the middle of the 1850s, the British and U.S. Navies were both building steam frigates with very long hulls and a heavy gun armament, for instance USS Merrimack or Mersey.[12]

The 1860s saw the introduction of the ironclad. The first ironclads were frigates, in the sense of having one gun deck; however, they were also clearly the most powerful ships in the navy, and were principally to serve in the line of battle. In spite of their great speed, they would have been wasted in a cruising role.[13]

The French constructed a number of smaller ironclads for overseas cruising duties, starting with the Belliqueuse, commissioned 1865. These "station ironclads" were the beginning of the development of the armored cruisers, a type of ironclad specifically for the traditional cruiser missions of fast, independent raiding and patrol.

The first true armored cruiser was the Russian General-Admiral, completed in 1874, and followed by the British Shannon a few years later.

Until the 1890s armored cruisers were still built with masts for a full sailing rig, to enable them to operate far from friendly coaling stations.[14]

Unarmored cruising warships, built out of wood, iron, steel or a combination of those materials, remained popular until towards the end of the 19th century. The ironclad's armor often meant that they were limited to short range under steam, and many ironclads were unsuited to long-range missions or for work in distant colonies. The unarmored cruiser—often a screw sloop or screw frigate—could continue in this role. Even though mid- to late-19th century cruisers typically carried up-to-date guns firing explosive shells, they were unable to face ironclads in combat. This was evidenced by the clash between HMS Shah, a modern British cruiser, and the Peruvian monitor Huáscar. Even though the Peruvian vessel was obsolete by the time of the encounter, it stood up well to roughly 50 hits from British shells.

Steel cruisers

In the 1880s, naval engineers began to use steel as a material for construction and armament. A steel cruiser could be lighter and faster than one built of iron or wood. The Jeune Ecole school of naval doctrine suggested that a fleet of fast unprotected steel cruisers were ideal for commerce raiding, while the torpedo boat would be able to destroy an enemy battleship fleet.

Steel also offered the cruiser a way of acquiring the protection needed to survive in combat. Steel armor was considerably stronger, for the same weight, than iron. By putting a relatively thin layer of steel armor above the vital parts of the ship, and by placing the coal bunkers where they might stop shellfire, a useful degree of protection could be achieved without slowing the ship too much. Protected cruisers generally had an armored deck with sloped sides, providing similar protection to a light armored belt at less weight and expense.

The first protected cruiser was the Chilean ship Esmeralda, launched in 1883. Produced by a shipyard at Elswick, in Britain, owned by Armstrong, she inspired a group of protected cruisers produced in the same yard and known as the "Elswick cruisers". Her forecastle, poop deck and the wooden board deck had been removed, replaced with an armored deck.

Esmeralda's armament consisted of fore and aft 10-inch (25.4 cm) guns and 6-inch (15.2 cm) guns in the midships positions. It could reach a speed of 18 knots (33 km/h), and was propelled by steam alone. It also had a displacement of less than 3,000 tons. During the two following decades, this cruiser type came to be the inspiration for combining heavy artillery, high speed and low displacement.

Torpedo cruisers

The torpedo cruiser (known in the Royal Navy as the torpedo gunboat) was a smaller unarmored cruiser, which emerged in the 1880s–1890s. These ships could reach speeds up to 20 knots (37 km/h) and were armed with medium to small calibre guns as well as torpedoes. These ships were tasked with guard and reconnaissance duties, to repeat signals and all other fleet duties for which smaller vessels were suited. These ships could also function as flagships of torpedo boat flotillas. After the 1900s, these ships were usually traded for faster ships with better sea going qualities.

Pre-dreadnought armored cruisers

Steel also affected the construction and role of armored cruisers. Steel meant that new designs of battleship, later known as pre-dreadnought battleships, would be able to combine firepower and armor with better endurance and speed than ever before. The armored cruisers of the 1890s and early 1900s greatly resembled the battleships of the day; they tended to carry slightly smaller main armament (7.5-to-10-inch (190 to 250 mm) rather than 12-inch) and have somewhat thinner armor in exchange for a faster speed (perhaps 21 to 23 knots (39 to 43 km/h) rather than 18). Because of their similarity, the lines between battleships and armored cruisers became blurred.

Early 20th century

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century there were difficult questions about the design of future cruisers. Modern armored cruisers, almost as powerful as battleships, were also fast enough to outrun older protected and unarmored cruisers. In the Royal Navy, Jackie Fisher cut back hugely on older vessels, including many cruisers of different sorts, calling them "a miser's hoard of useless junk" that any modern cruiser would sweep from the seas. The scout cruiser also appeared in this era; this was a small, fast, lightly armed and armored type designed primarily for reconnaissance. The Royal Navy and the Italian Navy were the primary developers of this type.

Battle cruisers

The growing size and power of the armored cruiser resulted in the battlecruiser, with an armament and size similar to the revolutionary new dreadnought battleship; the brainchild of British admiral Jackie Fisher. He believed that to ensure British naval dominance in its overseas colonial possessions, a fleet of large, fast, powerfully armed vessels which would be able to hunt down and mop up enemy cruisers and armored cruisers with overwhelming fire superiority was needed. They were equipped with the same gun types as battleships, though usually with fewer guns, and were intended to engage enemy capital ships as well. This type of vessel came to be known as the battlecruiser, and the first were commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1907. The British battlecruisers sacrificed protection for speed, as they were intended to "choose their range" (to the enemy) with superior speed and only engage the enemy at long range. When engaged at moderate ranges, the lack of protection combined with unsafe ammunition handling practices became tragic with the loss of three of them at the Battle of Jutland. Germany and eventually Japan followed suit to build these vessels, replacing armored cruisers in most frontline roles. German battlecruisers were generally better protected but slower than British battlecruisers. Battlecruisers were in many cases larger and more expensive than contemporary battleships, due to their much larger propulsion plants.

Light cruisers

At around the same time as the battlecruiser was developed, the distinction between the armored and the unarmored cruiser finally disappeared. By the British Town class, the first of which was launched in 1909, it was possible for a small, fast cruiser to carry both belt and deck armor, particularly when turbine engines were adopted. These light armored cruisers began to occupy the traditional cruiser role once it became clear that the battlecruiser squadrons were required to operate with the battle fleet.

Flotilla leaders

Some light cruisers were built specifically to act as the leaders of flotillas of destroyers.

Coastguard cruisers

These vessels were essentially large coastal patrol boats armed with multiple light guns. One such warship was Grivița of the Romanian Navy. She displaced 110 tons, measured 60 meters in length and was armed with four light guns.[15]

Auxiliary cruisers

The auxiliary cruiser was a merchant ship hastily armed with small guns on the outbreak of war. Auxiliary cruisers were used to fill gaps in their long-range lines or provide escort for other cargo ships, although they generally proved to be useless in this role because of their low speed, feeble firepower and lack of armor. In both world wars the Germans also used small merchant ships armed with cruiser guns to surprise Allied merchant ships.

Some large liners were armed in the same way. In British service these were known as Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMC). The Germans and French used them in World War I as raiders because of their high speed (around 30 knots (56 km/h)), and they were used again as raiders early in World War II by the Germans and Japanese. In both the First World War and in the early part of the Second, they were used as convoy escorts by the British.

World War I

Cruisers were one of the workhorse types of warship during World War I. By the time of World War I, cruisers had accelerated their development and improved their quality significantly, with drainage volume reaching 3000–4000 tons, a speed of 25–30 knots and a calibre of 127–152 mm.

Mid-20th century

Naval construction in the 1920s and 1930s was limited by international treaties designed to prevent the repetition of the Dreadnought arms race of the early 20th century. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 placed limits on the construction of ships with a standard displacement of more than 10,000 tons and an armament of guns larger than 8-inch (203 mm). A number of navies commissioned classes of cruisers at the top end of this limit, known as "treaty cruisers".[16]

The London Naval Treaty in 1930 then formalised the distinction between these "heavy" cruisers and light cruisers: a "heavy" cruiser was one with guns of more than 6.1-inch (155 mm) calibre.[17] The Second London Naval Treaty attempted to reduce the tonnage of new cruisers to 8,000 or less, but this had little effect; Japan and Germany were not signatories, and some navies had already begun to evade treaty limitations on warships. The first London treaty did touch off a period of the major powers building 6-inch or 6.1-inch gunned cruisers, nominally of 10,000 tons and with up to fifteen guns, the treaty limit. Thus, most light cruisers ordered after 1930 were the size of heavy cruisers but with more and smaller guns. The Imperial Japanese Navy began this new race with the Mogami class, launched in 1934.[18] After building smaller light cruisers with six or eight 6-inch guns launched 1931–35, the British Royal Navy followed with the 12-gun Southampton class in 1936.[19] To match foreign developments and potential treaty violations, in the 1930s the US developed a series of new guns firing "super-heavy" armor piercing ammunition; these included the 6-inch (152 mm)/47 caliber gun Mark 16 introduced with the 15-gun Brooklyn-class cruisers in 1936,[20] and the 8-inch (203 mm)/55 caliber gun Mark 12 introduced with USS Wichita in 1937.[21][22]

Heavy cruisers

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser designed for long range, high speed and an armament of naval guns around 203 mm (8 in) in calibre. The first heavy cruisers were built in 1915, although it only became a widespread classification following the London Naval Treaty in 1930. The heavy cruiser's immediate precursors were the light cruiser designs of the 1910s and 1920s; the US lightly armored 8-inch "treaty cruisers" of the 1920s (built under the Washington Naval Treaty) were originally classed as light cruisers until the London Treaty forced their redesignation.[23]

Initially, all cruisers built under the Washington treaty had torpedo tubes, regardless of nationality. However, in 1930, results of war games caused the US Naval War College to conclude that only perhaps half of cruisers would use their torpedoes in action. In a surface engagement, long-range gunfire and destroyer torpedoes would decide the issue, and under air attack numerous cruisers would be lost before getting within torpedo range. Thus, beginning with USS New Orleans launched in 1933, new cruisers were built without torpedoes, and torpedoes were removed from older heavy cruisers due to the perceived hazard of their being exploded by shell fire.[24] The Japanese took exactly the opposite approach with cruiser torpedoes, and this proved crucial to their tactical victories in most of the numerous cruiser actions of 1942. Beginning with the Furutaka class launched in 1925, every Japanese heavy cruiser was armed with 24-inch (610 mm) torpedoes, larger than any other cruisers'.[25] By 1933 Japan had developed the Type 93 torpedo for these ships, eventually nicknamed "Long Lance" by the Allies. This type used compressed oxygen instead of compressed air, allowing it to achieve ranges and speeds unmatched by other torpedoes. It could achieve a range of 22,000 metres (24,000 yd) at 50 knots (93 km/h; 58 mph), compared with the US Mark 15 torpedo with 5,500 metres (6,000 yd) at 45 knots (83 km/h; 52 mph). The Mark 15 had a maximum range of 13,500 metres (14,800 yd) at 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph), still well below the "Long Lance".[26] The Japanese were able to keep the Type 93's performance and oxygen power secret until the Allies recovered one in early 1943, thus the Allies faced a great threat they were not aware of in 1942. The Type 93 was also fitted to Japanese post-1930 light cruisers and the majority of their World War II destroyers.[25][27]

Heavy cruisers continued in use until after World War II, with some converted to guided-missile cruisers for air defense or strategic attack and some used for shore bombardment by the United States in the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

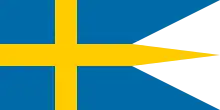

German pocket battleships

The German Deutschland class was a series of three Panzerschiffe ("armored ships"), a form of heavily armed cruiser, designed and built by the German Reichsmarine in nominal accordance with restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. All three ships were launched between 1931 and 1934, and served with Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. Within the Kriegsmarine, the Panzerschiffe had the propaganda value of capital ships: heavy cruisers with battleship guns, torpedoes, and scout aircraft. The similar Swedish Panzerschiffe were tactically used as centers of battlefleets and not as cruisers. They were deployed by Nazi Germany in support of the German interests in the Spanish Civil War. Panzerschiff Admiral Graf Spee represented Germany in the 1937 Coronation Fleet Review.

The British press referred to the vessels as pocket battleships, in reference to the heavy firepower contained in the relatively small vessels; they were considerably smaller than contemporary battleships, though at 28 knots were slower than battlecruisers. At up to 16,000 tons at full load, they were not treaty compliant 10,000 ton cruisers. And although their displacement and scale of armor protection were that of a heavy cruiser, their 280 mm (11 in) main armament was heavier than the 203 mm (8 in) guns of other nations' heavy cruisers, and the latter two members of the class also had tall conning towers resembling battleships. The Panzerschiffe were listed as Ersatz replacements for retiring Reichsmarine coastal defense battleships, which added to their propaganda status in the Kriegsmarine as Ersatz battleships; within the Royal Navy, only battlecruisers HMS Hood, HMS Repulse and HMS Renown were capable of both outrunning and outgunning the Panzerschiffe. They were seen in the 1930s as a new and serious threat by both Britain and France. While the Kriegsmarine reclassified them as heavy cruisers in 1940, Deutschland-class ships continued to be called pocket battleships in the popular press.

Large cruiser

The American Alaska class represented the supersized cruiser design. Due to the German pocket battleships, the Scharnhorst class, and rumored Japanese "super cruisers", all of which carried guns larger than the standard heavy cruiser's 8-inch size dictated by naval treaty limitations, the Alaskas were intended to be "cruiser-killers". While superficially appearing similar to a battleship/battlecruiser and mounting three triple turrets of 12-inch guns, their actual protection scheme and design resembled a scaled-up heavy cruiser design. Their hull classification symbol of CB (cruiser, big) reflected this.[28]

Anti-aircraft cruisers

A precursor to the anti-aircraft cruiser was the Romanian British-built protected cruiser Elisabeta. After the start of World War I, her four 120 mm main guns were landed and her four 75 mm (12-pounder) secondary guns were modified for anti-aircraft fire.[29]

The development of the anti-aircraft cruiser began in 1935 when the Royal Navy re-armed HMS Coventry and HMS Curlew. Torpedo tubes and 6-inch (152 mm) low-angle guns were removed from these World War I light cruisers and replaced with ten 4-inch (102 mm) high-angle guns, with appropriate fire-control equipment to provide larger warships with protection against high-altitude bombers.[30]

A tactical shortcoming was recognised after completing six additional conversions of C-class cruisers. Having sacrificed anti-ship weapons for anti-aircraft armament, the converted anti-aircraft cruisers might themselves need protection against surface units. New construction was undertaken to create cruisers of similar speed and displacement with dual-purpose guns, which offered good anti-aircraft protection with anti-surface capability for the traditional light cruiser role of defending capital ships from destroyers.

The first purpose built anti-aircraft cruiser was the British Dido class, completed in 1940–42. The US Navy's Atlanta-class cruisers (CLAA: light cruiser with anti-aircraft capability) were designed to match the capabilities of the Royal Navy. Both Dido and Atlanta cruisers initially carried torpedo tubes; the Atlanta cruisers at least were originally designed as destroyer leaders, were originally designated CL (light cruiser), and did not receive the CLAA designation until 1949.[31][32]

The concept of the quick-firing dual-purpose gun anti-aircraft cruiser was embraced in several designs completed too late to see combat, including: USS Worcester, completed in 1948; USS Roanoke, completed in 1949; two Tre Kronor-class cruisers, completed in 1947; two De Zeven Provinciën-class cruisers, completed in 1953; De Grasse, completed in 1955; Colbert, completed in 1959; and HMS Tiger, HMS Lion and HMS Blake, all completed between 1959 and 1961.[33]

Most post-World War II cruisers were tasked with air defense roles. In the early 1950s, advances in aviation technology forced the move from anti-aircraft artillery to anti-aircraft missiles. Therefore, most modern cruisers are equipped with surface-to-air missiles as their main armament. Today's equivalent of the anti-aircraft cruiser is the guided-missile cruiser (CAG/CLG/CG/CGN).

World War II

Cruisers participated in a number of surface engagements in the early part of World War II, along with escorting carrier and battleship groups throughout the war. In the later part of the war, Allied cruisers primarily provided anti-aircraft (AA) escort for carrier groups and performed shore bombardment. Japanese cruisers similarly escorted carrier and battleship groups in the later part of the war, notably in the disastrous Battle of the Philippine Sea and Battle of Leyte Gulf. In 1937–41 the Japanese, having withdrawn from all naval treaties, upgraded or completed the Mogami and Tone classes as heavy cruisers by replacing their 6.1 in (155 mm) triple turrets with 8 in (203 mm) twin turrets.[34] Torpedo refits were also made to most heavy cruisers, resulting in up to sixteen 24 in (610 mm) tubes per ship, plus a set of reloads.[35] In 1941 the 1920s light cruisers Ōi and Kitakami were converted to torpedo cruisers with four 5.5 in (140 mm) guns and forty 24 in (610 mm) torpedo tubes. In 1944 Kitakami was further converted to carry up to eight Kaiten human torpedoes in place of ordinary torpedoes.[36] Before World War II, cruisers were mainly divided into three types: heavy cruisers, light cruisers and auxiliary cruisers. Heavy cruiser tonnage reached 20–30,000 tons, speed 32–34 knots, endurance of more than 10,000 nautical miles, armor thickness of 127–203 mm. Heavy cruisers were equipped with eight or nine 8 in (203 mm) guns with a range of more than 20 nautical miles. They were mainly used to attack enemy surface ships and shore-based targets. In addition, there were 10–16 secondary guns with a caliber of less than 130 mm (5.1 in). Also, dozens of automatic antiaircraft guns were installed to fight aircraft and small vessels such as torpedo boats. For example, in World War II, American Alaska-class cruisers were more than 30,000 tons, equipped with nine 12 in (305 mm) guns. Some cruisers could also carry three or four seaplanes to correct the accuracy of gunfire and perform reconnaissance. Together with battleships, these heavy cruisers formed powerful naval task forces, which dominated the world's oceans for more than a century. After the signing of the Washington Treaty on Arms Limitation in 1922, the tonnage and quantity of battleships, aircraft carriers and cruisers were severely restricted. In order not to violate the treaty, countries began to develop light cruisers. Light cruisers of the 1920s had displacements of less than 10,000 tons and a speed of up to 35 knots. They were equipped with 6–12 main guns with a caliber of 127–133 mm (5–5.5 inches). In addition, they were equipped with 8–12 secondary guns under 127 mm (5 in) and dozens of small caliber cannons, as well as torpedoes and mines. Some ships also carried 2–4 seaplanes, mainly for reconnaissance. In 1930 the London Naval Treaty allowed large light cruisers to be built, with the same tonnage as heavy cruisers and armed with up to fifteen 155 mm (6.1 in) guns. The Japanese Mogami class were built to this treaty's limit, the Americans and British also built similar ships. However, in 1939 the Mogamis were refitted as heavy cruisers with ten 203 mm (8.0 in) guns.

1939 to Pearl Harbor

In December 1939, three British cruisers engaged the German "pocket battleship" Admiral Graf Spee (which was on a commerce raiding mission) in the Battle of the River Plate; German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee then took refuge in neutral Montevideo, Uruguay. By broadcasting messages indicating capital ships were in the area, the British caused Admiral Graf Spee's captain to think he faced a hopeless situation while low on ammunition and order his ship scuttled.[37] On 8 June 1940 the German capital ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, classed as battleships but with large cruiser armament, sank the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious with gunfire.[38] From October 1940 through March 1941 the German heavy cruiser (also known as "pocket battleship", see above) Admiral Scheer conducted a successful commerce-raiding voyage in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[39]

On 27 May 1941, HMS Dorsetshire attempted to finish off the German battleship Bismarck with torpedoes, probably causing the Germans to scuttle the ship.[40] Bismarck (accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen) previously sank the battlecruiser HMS Hood and damaged the battleship HMS Prince of Wales with gunfire in the Battle of the Denmark Strait.[41]

On 19 November 1941 HMAS Sydney sank in a mutually fatal engagement with the German raider Kormoran in the Indian Ocean near Western Australia.

Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Indian Ocean operations 1942–1944

Twenty-three British cruisers were lost to enemy action, mostly to air attack and submarines, in operations in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Indian Ocean. Sixteen of these losses were in the Mediterranean.[42] The British included cruisers and anti-aircraft cruisers among convoy escorts in the Mediterranean and to northern Russia due to the threat of surface and air attack. Almost all cruisers in World War II were vulnerable to submarine attack due to a lack of anti-submarine sonar and weapons. Also, until 1943–44 the light anti-aircraft armament of most cruisers was weak.

In July 1942 an attempt to intercept Convoy PQ 17 with surface ships, including the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, failed due to multiple German warships grounding, but air and submarine attacks sank 2/3 of the convoy's ships.[43] In August 1942 Admiral Scheer conducted Operation Wunderland, a solo raid into northern Russia's Kara Sea. She bombarded Dikson Island but otherwise had little success.[44]

On 31 December 1942 the Battle of the Barents Sea was fought, a rare action for a Murmansk run because it involved cruisers on both sides. Four British destroyers and five other vessels were escorting Convoy JW 51B from the UK to the Murmansk area. Another British force of two cruisers (HMS Sheffield and HMS Jamaica) and two destroyers were in the area. Two heavy cruisers (one the "pocket battleship" Lützow), accompanied by six destroyers, attempted to intercept the convoy near North Cape after it was spotted by a U-boat. Although the Germans sank a British destroyer and a minesweeper (also damaging another destroyer), they failed to damage any of the convoy's merchant ships. A German destroyer was lost and a heavy cruiser damaged. Both sides withdrew from the action for fear of the other side's torpedoes.[45]

On 26 December 1943 the German capital ship Scharnhorst was sunk while attempting to intercept a convoy in the Battle of the North Cape. The British force that sank her was led by Vice Admiral Bruce Fraser in the battleship HMS Duke of York, accompanied by four cruisers and nine destroyers. One of the cruisers was the preserved HMS Belfast.[46]

Scharnhorst's sister Gneisenau, damaged by a mine and a submerged wreck in the Channel Dash of 13 February 1942 and repaired, was further damaged by a British air attack on 27 February 1942. She began a conversion process to mount six 38 cm (15 in) guns instead of nine 28 cm (11 in) guns, but in early 1943 Hitler (angered by the recent failure at the Battle of the Barents Sea) ordered her disarmed and her armament used as coast defence weapons. One 28 cm triple turret survives near Trondheim, Norway.[47]

Pearl Harbor through Dutch East Indies campaign

The attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 brought the United States into the war, but with eight battleships sunk or damaged by air attack.[48] On 10 December 1941 HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse were sunk by land-based torpedo bombers northeast of Singapore. It was now clear that surface ships could not operate near enemy aircraft in daylight without air cover; most surface actions of 1942–43 were fought at night as a result. Generally, both sides avoided risking their battleships until the Japanese attack at Leyte Gulf in 1944.[49][50]

Six of the battleships from Pearl Harbor were eventually returned to service, but no US battleships engaged Japanese surface units at sea until the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942, and not thereafter until the Battle of Surigao Strait in October 1944.[51] USS North Carolina was on hand for the initial landings at Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942, and escorted carriers in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons later that month. However, on 15 September she was torpedoed while escorting a carrier group and had to return to the US for repairs.[51]

Generally, the Japanese held their capital ships out of all surface actions in the 1941–42 campaigns or they failed to close with the enemy; the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942 was the sole exception. The four Kongō-class ships performed shore bombardment in Malaya, Singapore, and Guadalcanal and escorted the raid on Ceylon and other carrier forces in 1941–42. Japanese capital ships also participated ineffectively (due to not being engaged) in the Battle of Midway and the simultaneous Aleutian diversion; in both cases they were in battleship groups well to the rear of the carrier groups. Sources state that Yamato sat out the entire Guadalcanal Campaign due to lack of high-explosive bombardment shells, poor nautical charts of the area, and high fuel consumption.[52][53] It is likely that the poor charts affected other battleships as well. Except for the Kongō class, most Japanese battleships spent the critical year of 1942, in which most of the war's surface actions occurred, in home waters or at the fortified base of Truk, far from any risk of attacking or being attacked.

From 1942 through mid-1943, US and other Allied cruisers were the heavy units on their side of the numerous surface engagements of the Dutch East Indies campaign, the Guadalcanal Campaign, and subsequent Solomon Islands fighting; they were usually opposed by strong Japanese cruiser-led forces equipped with Long Lance torpedoes. Destroyers also participated heavily on both sides of these battles and provided essentially all the torpedoes on the Allied side, with some battles in these campaigns fought entirely between destroyers.

Along with lack of knowledge of the capabilities of the Long Lance torpedo, the US Navy was hampered by a deficiency it was initially unaware of—the unreliability of the Mark 15 torpedo used by destroyers. This weapon shared the Mark 6 exploder and other problems with the more famously unreliable Mark 14 torpedo; the most common results of firing either of these torpedoes were a dud or a miss. The problems with these weapons were not solved until mid-1943, after almost all of the surface actions in the Solomon Islands had taken place.[54] Another factor that shaped the early surface actions was the pre-war training of both sides. The US Navy concentrated on long-range 8-inch gunfire as their primary offensive weapon, leading to rigid battle line tactics, while the Japanese trained extensively for nighttime torpedo attacks.[55][56] Since all post-1930 Japanese cruisers had 8-inch guns by 1941, almost all of the US Navy's cruisers in the South Pacific in 1942 were the 8-inch-gunned (203 mm) "treaty cruisers"; most of the 6-inch-gunned (152 mm) cruisers were deployed in the Atlantic.[55]

Dutch East Indies campaign

Although their battleships were held out of surface action, Japanese cruiser-destroyer forces rapidly isolated and mopped up the Allied naval forces in the Dutch East Indies campaign of February–March 1942. In three separate actions, they sank five Allied cruisers (two Dutch and one each British, Australian, and American) with torpedoes and gunfire, against one Japanese cruiser damaged.[57] With one other Allied cruiser withdrawn for repairs, the only remaining Allied cruiser in the area was the damaged USS Marblehead. Despite their rapid success, the Japanese proceeded methodically, never leaving their air cover and rapidly establishing new air bases as they advanced.[58]

Guadalcanal campaign

After the key carrier battles of the Coral Sea and Midway in mid-1942, Japan had lost four of the six fleet carriers that launched the Pearl Harbor raid and was on the strategic defensive. On 7 August 1942 US Marines were landed on Guadalcanal and other nearby islands, beginning the Guadalcanal Campaign. This campaign proved to be a severe test for the Navy as well as the Marines. Along with two carrier battles, several major surface actions occurred, almost all at night between cruiser-destroyer forces.

Battle of Savo Island

On the night of 8–9 August 1942 the Japanese counterattacked near Guadalcanal in the Battle of Savo Island with a cruiser-destroyer force. In a controversial move, the US carrier task forces were withdrawn from the area on the 8th due to heavy fighter losses and low fuel. The Allied force included six heavy cruisers (two Australian), two light cruisers (one Australian), and eight US destroyers.[59] Of the cruisers, only the Australian ships had torpedoes. The Japanese force included five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and one destroyer. Numerous circumstances combined to reduce Allied readiness for the battle. The results of the battle were three American heavy cruisers sunk by torpedoes and gunfire, one Australian heavy cruiser disabled by gunfire and scuttled, one heavy cruiser damaged, and two US destroyers damaged. The Japanese had three cruisers lightly damaged. This was the most lopsided outcome of the surface actions in the Solomon Islands. Along with their superior torpedoes, the opening Japanese gunfire was accurate and very damaging. Subsequent analysis showed that some of the damage was due to poor housekeeping practices by US forces. Stowage of boats and aircraft in midships hangars with full gas tanks contributed to fires, along with full and unprotected ready-service ammunition lockers for the open-mount secondary armament. These practices were soon corrected, and US cruisers with similar damage sank less often thereafter.[60] Savo was the first surface action of the war for almost all the US ships and personnel; few US cruisers and destroyers were targeted or hit at Coral Sea or Midway.

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

On 24–25 August 1942 the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, a major carrier action, was fought. Part of the action was a Japanese attempt to reinforce Guadalcanal with men and equipment on troop transports. The Japanese troop convoy was attacked by Allied aircraft, resulting in the Japanese subsequently reinforcing Guadalcanal with troops on fast warships at night. These convoys were called the "Tokyo Express" by the Allies. Although the Tokyo Express often ran unopposed, most surface actions in the Solomons revolved around Tokyo Express missions. Also, US air operations had commenced from Henderson Field, the airfield on Guadalcanal. Fear of air power on both sides resulted in all surface actions in the Solomons being fought at night.

Battle of Cape Esperance

The Battle of Cape Esperance occurred on the night of 11–12 October 1942. A Tokyo Express mission was underway for Guadalcanal at the same time as a separate cruiser-destroyer bombardment group loaded with high explosive shells for bombarding Henderson Field. A US cruiser-destroyer force was deployed in advance of a convoy of US Army troops for Guadalcanal that was due on 13 October. The Tokyo Express convoy was two seaplane tenders and six destroyers; the bombardment group was three heavy cruisers and two destroyers, and the US force was two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and five destroyers. The US force engaged the Japanese bombardment force; the Tokyo Express convoy was able to unload on Guadalcanal and evade action. The bombardment force was sighted at close range (5,000 yards (4,600 m)) and the US force opened fire. The Japanese were surprised because their admiral was anticipating sighting the Tokyo Express force, and withheld fire while attempting to confirm the US ships' identity.[61] One Japanese cruiser and one destroyer were sunk and one cruiser damaged, against one US destroyer sunk with one light cruiser and one destroyer damaged. The bombardment force failed to bring its torpedoes into action, and turned back. The next day US aircraft from Henderson Field attacked several of the Japanese ships, sinking two destroyers and damaging a third.[62] The US victory resulted in overconfidence in some later battles, reflected in the initial after-action report claiming two Japanese heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and three destroyers sunk by the gunfire of Boise alone.[60] The battle had little effect on the overall situation, as the next night two Kongō-class battleships bombarded and severely damaged Henderson Field unopposed, and the following night another Tokyo Express convoy delivered 4,500 troops to Guadalcanal. The US convoy delivered the Army troops as scheduled on the 13th.[63]

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands took place 25–27 October 1942. It was a pivotal battle, as it left the US and Japanese with only two large carriers each in the South Pacific (another large Japanese carrier was damaged and under repair until May 1943). Due to the high carrier attrition rate with no replacements for months, for the most part both sides stopped risking their remaining carriers until late 1943, and each side sent in a pair of battleships instead. The next major carrier operations for the US were the carrier raid on Rabaul and support for the invasion of Tarawa, both in November 1943.

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal occurred 12–15 November 1942 in two phases. A night surface action on 12–13 November was the first phase. The Japanese force consisted of two Kongō-class battleships with high explosive shells for bombarding Henderson Field, one small light cruiser, and 11 destroyers. Their plan was that the bombardment would neutralize Allied airpower and allow a force of 11 transport ships and 12 destroyers to reinforce Guadalcanal with a Japanese division the next day.[64] However, US reconnaissance aircraft spotted the approaching Japanese on the 12th and the Americans made what preparations they could. The American force consisted of two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, two anti-aircraft cruisers,[65] and eight destroyers. The Americans were outgunned by the Japanese that night, and a lack of pre-battle orders by the US commander led to confusion. The destroyer USS Laffey closed with the battleship Hiei, firing all torpedoes (though apparently none hit or detonated) and raking the battleship's bridge with gunfire, wounding the Japanese admiral and killing his chief of staff. The Americans initially lost four destroyers including Laffey, with both heavy cruisers, most of the remaining destroyers, and both anti-aircraft cruisers damaged. The Japanese initially had one battleship and four destroyers damaged, but at this point they withdrew, possibly unaware that the US force was unable to further oppose them.[64] At dawn US aircraft from Henderson Field, USS Enterprise, and Espiritu Santo found the damaged battleship and two destroyers in the area. The battleship (Hiei) was sunk by aircraft (or possibly scuttled), one destroyer was sunk by the damaged USS Portland, and the other destroyer was attacked by aircraft but was able to withdraw.[64] Both of the damaged US anti-aircraft cruisers were lost on 13 November, one (Juneau) torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, and the other sank on the way to repairs. Juneau's loss was especially tragic; the submarine's presence prevented immediate rescue, over 100 survivors of a crew of nearly 700 were adrift for eight days, and all but ten died. Among the dead were the five Sullivan brothers.[66]

The Japanese transport force was rescheduled for the 14th and a new cruiser-destroyer force (belatedly joined by the surviving battleship Kirishima) was sent to bombard Henderson Field the night of 13 November. Only two cruisers actually bombarded the airfield, as Kirishima had not arrived yet and the remainder of the force was on guard for US warships. The bombardment caused little damage. The cruiser-destroyer force then withdrew, while the transport force continued towards Guadalcanal. Both forces were attacked by US aircraft on the 14th. The cruiser force lost one heavy cruiser sunk and one damaged. Although the transport force had fighter cover from the carrier Jun'yō, six transports were sunk and one heavily damaged. All but four of the destroyers accompanying the transport force picked up survivors and withdrew. The remaining four transports and four destroyers approached Guadalcanal at night, but stopped to await the results of the night's action.[64]

On the night of 14–15 November a Japanese force of Kirishima, two heavy and two light cruisers, and nine destroyers approached Guadalcanal. Two US battleships (Washington and South Dakota) were there to meet them, along with four destroyers. This was one of only two battleship-on-battleship encounters during the Pacific War; the other was the lopsided Battle of Surigao Strait in October 1944, part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The battleships had been escorting Enterprise, but were detached due to the urgency of the situation. With nine 16-inch (406 mm) guns apiece against eight 14-inch (356 mm) guns on Kirishima, the Americans had major gun and armor advantages. All four destroyers were sunk or severely damaged and withdrawn shortly after the Japanese attacked them with gunfire and torpedoes.[64] Although her main battery remained in action for most of the battle, South Dakota spent much of the action dealing with major electrical failures that affected her radar, fire control, and radio systems. Although her armor was not penetrated, she was hit by 26 shells of various calibers and temporarily rendered, in a US admiral's words, "deaf, dumb, blind, and impotent".[64][51] Washington went undetected by the Japanese for most of the battle, but withheld shooting to avoid "friendly fire" until South Dakota was illuminated by Japanese fire, then rapidly set Kirishima ablaze with a jammed rudder and other damage. Washington, finally spotted by the Japanese, then headed for the Russell Islands to hopefully draw the Japanese away from Guadalcanal and South Dakota, and was successful in evading several torpedo attacks. Unusually, only a few Japanese torpedoes scored hits in this engagement. Kirishima sank or was scuttled before the night was out, along with two Japanese destroyers. The remaining Japanese ships withdrew, except for the four transports, which beached themselves in the night and started unloading. However, dawn (and US aircraft, US artillery, and a US destroyer) found them still beached, and they were destroyed.[64]

Battle of Tassafaronga

The Battle of Tassafaronga took place on the night of 30 November – 1 December 1942. The US had four heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and four destroyers. The Japanese had eight destroyers on a Tokyo Express run to deliver food and supplies in drums to Guadalcanal. The Americans achieved initial surprise, damaging one destroyer with gunfire which later sank, but the Japanese torpedo counterattack was devastating. One American heavy cruiser was sunk and three others heavily damaged, with the bows blown off of two of them.[67] It was significant that these two were not lost to Long Lance hits as happened in previous battles; American battle readiness and damage control had improved.[60] Despite defeating the Americans, the Japanese withdrew without delivering the crucial supplies to Guadalcanal. Another attempt on 3 December dropped 1,500 drums of supplies near Guadalcanal, but Allied strafing aircraft sank all but 300 before the Japanese Army could recover them. On 7 December PT boats interrupted a Tokyo Express run, and the following night sank a Japanese supply submarine. The next day the Japanese Navy proposed stopping all destroyer runs to Guadalcanal, but agreed to do just one more. This was on 11 December and was also intercepted by PT boats, which sank a destroyer; only 200 of 1,200 drums dropped off the island were recovered.[68] The next day the Japanese Navy proposed abandoning Guadalcanal; this was approved by the Imperial General Headquarters on 31 December and the Japanese left the island in early February 1943.[69]

Post-Guadalcanal

After the Japanese abandoned Guadalcanal in February 1943, Allied operations in the Pacific shifted to the New Guinea campaign and isolating Rabaul. The Battle of Kula Gulf was fought on the night of 5–6 July. The US had three light cruisers and four destroyers; the Japanese had ten destroyers loaded with 2,600 troops destined for Vila to oppose a recent US landing on Rendova. Although the Japanese sank a cruiser, they lost two destroyers and were able to deliver only 850 troops.[70] On the night of 12–13 July, the Battle of Kolombangara occurred. The Allies had three light cruisers (one New Zealand) and ten destroyers; the Japanese had one small light cruiser and five destroyers, a Tokyo Express run for Vila. All three Allied cruisers were heavily damaged, with the New Zealand cruiser put out of action for 25 months by a Long Lance hit.[71] The Allies sank only the Japanese light cruiser, and the Japanese landed 1,200 troops at Vila. Despite their tactical victory, this battle caused the Japanese to use a different route in the future, where they were more vulnerable to destroyer and PT boat attacks.[70]

The Battle of Empress Augusta Bay was fought on the night of 1–2 November 1943, immediately after US Marines invaded Bougainville in the Solomon Islands. A Japanese heavy cruiser was damaged by a nighttime air attack shortly before the battle; it is likely that Allied airborne radar had progressed far enough to allow night operations. The Americans had four of the new Cleveland-class cruisers and eight destroyers. The Japanese had two heavy cruisers, two small light cruisers, and six destroyers. Both sides were plagued by collisions, shells that failed to explode, and mutual skill in dodging torpedoes. The Americans suffered significant damage to three destroyers and light damage to a cruiser, but no losses. The Japanese lost one light cruiser and a destroyer, with four other ships damaged. The Japanese withdrew; the Americans pursued them until dawn, then returned to the landing area to provide anti-aircraft cover.[72]

After the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in October 1942, both sides were short of large aircraft carriers. The US suspended major carrier operations until sufficient carriers could be completed to destroy the entire Japanese fleet at once should it appear. The Central Pacific carrier raids and amphibious operations commenced in November 1943 with a carrier raid on Rabaul (preceded and followed by Fifth Air Force attacks) and the bloody but successful invasion of Tarawa. The air attacks on Rabaul crippled the Japanese cruiser force, with four heavy and two light cruisers damaged; they were withdrawn to Truk. The US had built up a force in the Central Pacific of six large, five light, and six escort carriers prior to commencing these operations.

From this point on, US cruisers primarily served as anti-aircraft escorts for carriers and in shore bombardment. The only major Japanese carrier operation after Guadalcanal was the disastrous (for Japan) Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, nicknamed the "Marianas Turkey Shoot" by the US Navy.

Leyte Gulf

The Imperial Japanese Navy's last major operation was the Battle of Leyte Gulf, an attempt to dislodge the American invasion of the Philippines in October 1944. The two actions at this battle in which cruisers played a significant role were the Battle off Samar and the Battle of Surigao Strait.

Battle of Surigao Strait

The Battle of Surigao Strait was fought on the night of 24–25 October, a few hours before the Battle off Samar. The Japanese had a small battleship group composed of Fusō and Yamashiro, one heavy cruiser, and four destroyers. They were followed at a considerable distance by another small force of two heavy cruisers, a small light cruiser, and four destroyers. Their goal was to head north through Surigao Strait and attack the invasion fleet off Leyte. The Allied force, known as the 7th Fleet Support Force, guarding the strait was overwhelming. It included six battleships (all but one previously damaged in 1941 at Pearl Harbor), four heavy cruisers (one Australian), four light cruisers, and 28 destroyers, plus a force of 39 PT boats. The only advantage to the Japanese was that most of the Allied battleships and cruisers were loaded mainly with high explosive shells, although a significant number of armor-piercing shells were also loaded. The lead Japanese force evaded the PT boats' torpedoes, but were hit hard by the destroyers' torpedoes, losing a battleship. Then they encountered the battleship and cruiser guns. Only one destroyer survived. The engagement is notable for being one of only two occasions in which battleships fired on battleships in the Pacific Theater, the other being the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Due to the starting arrangement of the opposing forces, the Allied force was in a "crossing the T" position, so this was the last battle in which this occurred, but it was not a planned maneuver. The following Japanese cruiser force had several problems, including a light cruiser damaged by a PT boat and two heavy cruisers colliding, one of which fell behind and was sunk by air attack the next day.[73] An American veteran of Surigao Strait, USS Phoenix, was transferred to Argentina in 1951 as General Belgrano, becoming most famous for being sunk by HMS Conqueror in the Falklands War on 2 May 1982. She was the first ship sunk by a nuclear submarine outside of accidents, and only the second ship sunk by a submarine since World War II.[74]

Battle off Samar

At the Battle off Samar, a Japanese battleship group moving towards the invasion fleet off Leyte engaged a minuscule American force known as "Taffy 3" (formally Task Unit 77.4.3), composed of six escort carriers with about 28 aircraft each, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. The biggest guns in the American force were 5 in (127 mm)/38 caliber guns, while the Japanese had 14 in (356 mm), 16 in (406 mm), and 18.1 in (460 mm) guns. Aircraft from six additional escort carriers also participated for a total of around 330 US aircraft, a mix of F6F Hellcat fighters and TBF Avenger torpedo bombers. The Japanese had four battleships including Yamato, six heavy cruisers, two small light cruisers, and 11 destroyers. The Japanese force had earlier been driven off by air attack, losing Yamato's sister Musashi. Admiral Halsey then decided to use his Third Fleet carrier force to attack the Japanese carrier group, located well to the north of Samar, which was actually a decoy group with few aircraft. The Japanese were desperately short of aircraft and pilots at this point in the war, and Leyte Gulf was the first battle in which kamikaze attacks were used. Due to a tragedy of errors, Halsey took the American battleship force with him, leaving San Bernardino Strait guarded only by the small Seventh Fleet escort carrier force. The battle commenced at dawn on 25 October 1944, shortly after the Battle of Surigao Strait. In the engagement that followed, the Americans exhibited uncanny torpedo accuracy, blowing the bows off several Japanese heavy cruisers. The escort carriers' aircraft also performed very well, attacking with machine guns after their carriers ran out of bombs and torpedoes. The unexpected level of damage, and maneuvering to avoid the torpedoes and air attacks, disorganized the Japanese and caused them to think they faced at least part of the Third Fleet's main force. They had also learned of the defeat a few hours before at Surigao Strait, and did not hear that Halsey's force was busy destroying the decoy fleet. Convinced that the rest of the Third Fleet would arrive soon if it hadn't already, the Japanese withdrew, eventually losing three heavy cruisers sunk with three damaged to air and torpedo attacks. The Americans lost two escort carriers, two destroyers, and one destroyer escort sunk, with three escort carriers, one destroyer, and two destroyer escorts damaged, thus losing over one-third of their engaged force sunk with nearly all the remainder damaged.[73]

Wartime cruiser production

The US built cruisers in quantity through the end of the war, notably 14 Baltimore-class heavy cruisers and 27 Cleveland-class light cruisers, along with eight Atlanta-class anti-aircraft cruisers. The Cleveland class was the largest cruiser class ever built in number of ships completed, with nine additional Clevelands completed as light aircraft carriers. The large number of cruisers built was probably due to the significant cruiser losses of 1942 in the Pacific theater (seven American and five other Allied) and the perceived need for several cruisers to escort each of the numerous Essex-class aircraft carriers being built.[55] Losing four heavy and two small light cruisers in 1942, the Japanese built only five light cruisers during the war; these were small ships with six 6.1 in (155 mm) guns each.[75] Losing 20 cruisers in 1940–42, the British completed no heavy cruisers, thirteen light cruisers (Fiji and Minotaur classes), and sixteen anti-aircraft cruisers (Dido class) during the war.[76]

Late 20th century

The rise of air power during World War II dramatically changed the nature of naval combat. Even the fastest cruisers could not maneuver quickly enough to evade aerial attack, and aircraft now had torpedoes, allowing moderate-range standoff capabilities. This change led to the end of independent operations by single ships or very small task groups, and for the second half of the 20th century naval operations were based on very large fleets believed able to fend off all but the largest air attacks, though this was not tested by any war in that period. The US Navy became centered around carrier groups, with cruisers and battleships primarily providing anti-aircraft defense and shore bombardment. Until the Harpoon missile entered service in the late 1970s, the US Navy was almost entirely dependent on carrier-based aircraft and submarines for conventionally attacking enemy warships. Lacking aircraft carriers, the Soviet Navy depended on anti-ship cruise missiles; in the 1950s these were primarily delivered from heavy land-based bombers. Soviet submarine-launched cruise missiles at the time were primarily for land attack; but by 1964 anti-ship missiles were deployed in quantity on cruisers, destroyers, and submarines.[77]

US cruiser development

The US Navy was aware of the potential missile threat as soon as World War II ended, and had considerable related experience due to Japanese kamikaze attacks in that war. The initial response was to upgrade the light AA armament of new cruisers from 40 mm and 20 mm weapons to twin 3-inch (76 mm)/50 caliber gun mounts.[78] For the longer term, it was thought that gun systems would be inadequate to deal with the missile threat, and by the mid-1950s three naval SAM systems were developed: Talos (long range), Terrier (medium range), and Tartar (short range).[79] Talos and Terrier were nuclear-capable and this allowed their use in anti-ship or shore bombardment roles in the event of nuclear war.[80] Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke is credited with speeding the development of these systems.[81]

Terrier was initially deployed on two converted Baltimore-class cruisers (CAG), with conversions completed in 1955–56.[79] Further conversions of six Cleveland-class cruisers (CLG) (Galveston and Providence classes), redesign of the Farragut class as guided-missile "frigates" (DLG),[82] and development of the Charles F. Adams-class DDGs[83] resulted in the completion of numerous additional guided-missile ships deploying all three systems in 1959–1962. Also completed during this period was the nuclear-powered USS Long Beach, with two Terrier and one Talos launchers, plus an ASROC anti-submarine launcher the World War II conversions lacked.[84] The converted World War II cruisers up to this point retained one or two main battery turrets for shore bombardment. However, in 1962–1964 three additional Baltimore and Oregon City-class cruisers were more extensively converted as the Albany class. These had two Talos and two Tartar launchers plus ASROC and two 5-inch (127 mm) guns for self-defense, and were primarily built to get greater numbers of Talos launchers deployed.[84] Of all these types, only the Farragut DLGs were selected as the design basis for further production, although their Leahy-class successors were significantly larger (5,670 tons standard versus 4,150 tons standard) due to a second Terrier launcher and greater endurance.[85][86] An economical crew size compared with World War II conversions was probably a factor, as the Leahys required a crew of only 377 versus 1,200 for the Cleveland-class conversions.[87] Through 1980, the ten Farraguts were joined by four additional classes and two one-off ships for a total of 36 guided-missile frigates, eight of them nuclear-powered (DLGN). In 1975 the Farraguts were reclassified as guided-missile destroyers (DDG) due to their small size, and the remaining DLG/DLGN ships became guided-missile cruisers (CG/CGN).[85] The World War II conversions were gradually retired between 1970 and 1980; the Talos missile was withdrawn in 1980 as a cost-saving measure and the Albanys were decommissioned. Long Beach had her Talos launcher removed in a refit shortly thereafter; the deck space was used for Harpoon missiles.[88] Around this time the Terrier ships were upgraded with the RIM-67 Standard ER missile.[89] The guided-missile frigates and cruisers served in the Cold War and the Vietnam War; off Vietnam they performed shore bombardment and shot down enemy aircraft or, as Positive Identification Radar Advisory Zone (PIRAZ) ships, guided fighters to intercept enemy aircraft.[90] By 1995 the former guided-missile frigates were replaced by the Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Arleigh Burke-class destroyers.[91]

The U.S. Navy's guided-missile cruisers were built upon destroyer-style hulls (some called "destroyer leaders" or "frigates" prior to the 1975 reclassification). As the U.S. Navy's strike role was centered around aircraft carriers, cruisers were primarily designed to provide air defense while often adding anti-submarine capabilities. These U.S. cruisers that were built in the 1960s and 1970s were larger, often nuclear-powered for extended endurance in escorting nuclear-powered fleet carriers, and carried longer-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) than early Charles F. Adams guided-missile destroyers that were tasked with the short-range air defense role. The U.S. cruiser was a major contrast to their contemporaries, Soviet "rocket cruisers" that were armed with large numbers of anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) as part of the combat doctrine of saturation attack, though in the early 1980s the U.S. Navy retrofitted some of these existing cruisers to carry a small number of Harpoon anti-ship missiles and Tomahawk cruise missiles.

The line between U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers blurred with the Spruance class. While originally designed for anti-submarine warfare, a Spruance destroyer was comparable in size to existing U.S. cruisers, while having the advantage of an enclosed hangar (with space for up to two medium-lift helicopters) which was a considerable improvement over the basic aviation facilities of earlier cruisers. The Spruance hull design was used as the basis for two classes; the Kidd class which had comparable anti-air capabilities to cruisers at the time, and then the DDG-47-class destroyers which were redesignated as the Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruisers to emphasize the additional capability provided by the ships' Aegis combat systems, and their flag facilities suitable for an admiral and his staff. In addition, 24 members of the Spruance class were upgraded with the vertical launch system (VLS) for Tomahawk cruise missiles due to its modular hull design, along with the similarly VLS-equipped Ticonderoga class, these ships had anti-surface strike capabilities beyond the 1960s–1970s cruisers that received Tomahawk armored-box launchers as part of the New Threat Upgrade. Like the Ticonderoga ships with VLS, the Arleigh Burke and Zumwalt class, despite being classified as destroyers, actually have much heavier anti-surface armament than previous U.S. ships classified as cruisers.

US Navy "cruiser gap"

Prior to the introduction of the Ticonderogas, the US Navy used odd naming conventions that left its fleet seemingly without many cruisers, although a number of their ships were cruisers in all but name. From the 1950s to the 1970s, US Navy cruisers were large vessels equipped with heavy, specialized missiles (mostly surface-to-air, but for several years including the Regulus nuclear cruise missile) for wide-ranging combat against land-based and sea-based targets. All save one—USS Long Beach—were converted from World War II cruisers of the Oregon City, Baltimore and Cleveland classes. Long Beach was also the last cruiser built with a World War II-era cruiser style hull (characterized by a long lean hull);[92][93] later new-build cruisers were actually converted frigates (DLG/CG USS Bainbridge, USS Truxtun, and the Leahy, Belknap, California, and Virginia classes) or uprated destroyers (the DDG/CG Ticonderoga class was built on a Spruance-class destroyer hull).

Frigates under this scheme were almost as large as the cruisers and optimized for anti-aircraft warfare, although they were capable anti-surface warfare combatants as well. In the late 1960s, the US government perceived a "cruiser gap"—at the time, the US Navy possessed six ships designated as cruisers, compared to 19 for the Soviet Union, even though the USN had 21 ships designated as frigates with equal or superior capabilities to the Soviet cruisers at the time. Because of this, in 1975 the Navy performed a massive redesignation of its forces:

- CVA/CVAN (Attack Aircraft Carrier/Nuclear-powered Attack Aircraft Carrier) were redesignated CV/CVN (although USS Midway and USS Coral Sea never embarked anti-submarine squadrons).

- DLG/DLGN (Frigates/Nuclear-powered Frigates) of the Leahy, Belknap, and California classes along with USS Bainbridge and USS Truxtun were redesignated CG/CGN (Guided-Missile Cruiser/Nuclear-powered Guided-Missile Cruiser).

- Farragut-class guided-missile frigates (DLG), being smaller and less capable than the others, were redesignated to DDGs (USS Coontz was the first ship of this class to be re-numbered; because of this the class is sometimes called the Coontz class);

- DE/DEG (Ocean Escort/Guided-Missile Ocean Escort) were redesignated to FF/FFG (Guided-Missile Frigates), bringing the US "Frigate" designation into line with the rest of the world.

Also, a series of Patrol Frigates of the Oliver Hazard Perry class, originally designated PFG, were redesignated into the FFG line. The cruiser-destroyer-frigate realignment and the deletion of the Ocean Escort type brought the US Navy's ship designations into line with the rest of the world's, eliminating confusion with foreign navies. In 1980, the Navy's then-building DDG-47-class destroyers were redesignated as cruisers (Ticonderoga guided-missile cruisers) to emphasize the additional capability provided by the ships' Aegis combat systems, and their flag facilities suitable for an admiral and his staff.

Soviet cruiser development

In the Soviet Navy, cruisers formed the basis of combat groups. In the immediate post-war era it built a fleet of gun-armed light cruisers, but replaced these beginning in the early 1960s with large ships called "rocket cruisers", carrying large numbers of anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) and anti-aircraft missiles. The Soviet combat doctrine of saturation attack meant that their cruisers (as well as destroyers and even missile boats) mounted multiple missiles in large container/launch tube housings and carried far more ASCMs than their NATO counterparts, while NATO combatants instead used individually smaller and lighter missiles (while appearing under-armed when compared to Soviet ships).

In 1962–1965 the four Kynda-class cruisers entered service; these had launchers for eight long-range SS-N-3 Shaddock ASCMs with a full set of reloads; these had a range of up to 450 kilometres (280 mi) with mid-course guidance.[94] The four more modest Kresta I-class cruisers, with launchers for four SS-N-3 ASCMs and no reloads, entered service in 1967–69.[95] In 1969–79 Soviet cruiser numbers more than tripled with ten Kresta II-class cruisers and seven Kara-class cruisers entering service. These had launchers for eight large-diameter missiles whose purpose was initially unclear to NATO. This was the SS-N-14 Silex, an over/under rocket-delivered heavyweight torpedo primarily for the anti-submarine role, but capable of anti-surface action with a range of up to 90 kilometres (56 mi). Soviet doctrine had shifted; powerful anti-submarine vessels (these were designated "Large Anti-Submarine Ships", but were listed as cruisers in most references) were needed to destroy NATO submarines to allow Soviet ballistic missile submarines to get within range of the United States in the event of nuclear war. By this time Long Range Aviation and the Soviet submarine force could deploy numerous ASCMs. Doctrine later shifted back to overwhelming carrier group defenses with ASCMs, with the Slava and Kirov classes.[96]

Current cruisers

_20210319.jpg.webp)

The most recent Soviet/Russian rocket cruisers, the four Kirov-class battlecruisers, were built in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the Kirov class is in refit, and 2 are being scrapped, with the Pyotr Velikiy in active service. Russia also operates two Slava-class cruisers and one Admiral Kuznetsov-class carrier which is officially designated as a cruiser, specifically a "heavy aviation cruiser" (Russian: тяжелый авианесущий крейсер) due to her complement of 12 P-700 Granit supersonic AShMs.

Currently, the Kirov-class heavy missile cruisers are used for command purposes, as Pyotr Velikiy is the flagship of the Northern Fleet. However, their air defense capabilities are still powerful, as shown by the array of point defense missiles they carry, from 44 OSA-MA missiles to 196 9K311 Tor missiles. For longer range targets, the S-300 is used. For closer range targets, AK-630 or Kashtan CIWSs are used. Aside from that, Kirovs have 20 P-700 Granit missiles for anti-ship warfare. For target acquisition beyond the radar horizon, three helicopters can be used. Besides a vast array of armament, Kirov-class cruisers are also outfitted with many sensors and communications equipment, allowing them to lead the fleet.

The United States Navy has centered on the aircraft carrier since World War II. The Ticonderoga-class cruisers, built in the 1980s, were originally designed and designated as a class of destroyer, intended to provide a very powerful air-defense in these carrier-centered fleets. Outside the US and Soviet navies, new cruisers were rare following World War II. Most navies use guided-missile destroyers for fleet air defense, and destroyers and frigates for cruise missiles. The need to operate in task forces has led most navies to change to fleets designed around ships dedicated to a single role, anti-submarine or anti-aircraft typically, and the large "generalist" ship has disappeared from most forces. The United States Navy, the Russian Navy and the Italian Navy are the only remaining navies which operate active duty cruisers. Italy used Vittorio Veneto until 2003 (decommissioned in 2006) and continues to use Giuseppe Garibaldi as of 2023; France operated a single helicopter cruiser until May 2010, Jeanne d'Arc, for training purposes only. While Type 055 of the Chinese Navy is classified as a cruiser by the U.S. Department of Defense, the Chinese consider it a guided-missile destroyer.[97]

In the years since the launch of Ticonderoga in 1981, the class has received a number of upgrades that have dramatically improved its members' capabilities for anti-submarine and land attack (using the Tomahawk missile). Like their Soviet counterparts, the modern Ticonderogas can also be used as the basis for an entire battle group. Their cruiser designation was almost certainly deserved when first built, as their sensors and combat management systems enable them to act as flagships for a surface warship flotilla if no carrier is present, but newer ships rated as destroyers and also equipped with Aegis approach them very closely in capability, and once more blur the line between the two classes.

If the Ukrainian account of the sinking of the Russian cruiser Moskva is proven correct then it raises questions about the vulnerability of surface ships against cruise missiles. The ship was only hit by two brand new, and virtually untested, R-360 Neptune missiles.[98][99]

Aircraft cruisers

From time to time, some navies have experimented with aircraft-carrying cruisers. One example is the Swedish Gotland. Another was the Japanese Mogami, which was converted to carry a large floatplane group in 1942. Another variant is the helicopter cruiser. The last example in service was the Soviet Navy's Kiev class, whose last unit Admiral Gorshkov was converted to a pure aircraft carrier and sold to India as INS Vikramaditya. The Russian Navy's Admiral Kuznetsov is nominally designated as an aviation cruiser but otherwise resembles a standard medium aircraft carrier, albeit with a surface-to-surface missile battery. The Royal Navy's aircraft-carrying Invincible class and the Italian Navy's aircraft-carrying Giuseppe Garibaldi vessels were originally designated 'through-deck cruisers', but have since been designated as small aircraft carriers (although the 'C' in the pennant for Giuseppe Garibaldi indicates it retains some status as an aircraft-carrying cruiser). Similarly, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force's Hyūga-class "helicopter destroyers" are really more along the lines of helicopter cruisers in function and aircraft complement, but due to the Treaty of San Francisco, must be designated as destroyers.[100]

One cruiser alternative studied in the late 1980s by the United States was variously entitled a Mission Essential Unit (MEU) or CG V/STOL. In a return to the thoughts of the independent operations cruiser-carriers of the 1930s and the Soviet Kiev class, the ship was to be fitted with a hangar, elevators, and a flight deck. The mission systems were Aegis, SQS-53 sonar, 12 SV-22 ASW aircraft and 200 VLS cells. The resulting ship would have had a waterline length of 700 feet, a waterline beam of 97 feet, and a displacement of about 25,000 tons. Other features included an integrated electric drive and advanced computer systems, both stand-alone and networked. It was part of the U.S. Navy's "Revolution at Sea" effort. The project was curtailed by the sudden end of the Cold War and its aftermath, otherwise the first of class would have been likely ordered in the early 1990s.

Operators

Few cruisers are still operational in the world's navies. Those that remain in service today are:

Hellenic Navy: The cruiser Georgios Averof is kept in ceremonial commission as the flagship of the Hellenic Navy due to her historical significance.

Hellenic Navy: The cruiser Georgios Averof is kept in ceremonial commission as the flagship of the Hellenic Navy due to her historical significance. Russian Navy: 2 Kirov class and 2 Slava-class guided-missile cruisers, the cruiser Aurora was ceremonially recommissioned as the flagship of the Russian Navy due to her historical significance.

Russian Navy: 2 Kirov class and 2 Slava-class guided-missile cruisers, the cruiser Aurora was ceremonially recommissioned as the flagship of the Russian Navy due to her historical significance. United States Navy: 15 Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruisers in service.[101] 5 more in the Reserve Fleet.

United States Navy: 15 Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruisers in service.[101] 5 more in the Reserve Fleet.

The following is laid up:

Ukrainian Navy: The cruiser Ukraina is a Slava-class cruiser that was under construction during the breakup of the Soviet Union. Ukraine inherited the ship following its independence. Progress to complete the ship has been slow and has been at 95% complete since circa 1995. It is estimated that an additional US$30 million are needed to complete the ship, and in 2019 Ukroboronprom announced that the ship would be sold.[102] The cruiser sits docked and unfinished at the harbor of Mykolaiv in southern Ukraine.[103] It was reported that the Ukrainian government invested ₴6.08 million into the ship's maintenance in 2012.[104] On 26 March 2017, it was announced that the Ukrainian Government will be scrapping the vessel which has been laid up, incomplete, for nearly 30 years in Mykolaiv. Maintenance and construction was costing the country US$225,000 per month. On 19 September 2019, the new director of Ukroboronprom Aivaras Abromavičius announced that the ship will be sold.[102] Her current status is unknown due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.