IgG deficiency

IgG deficiency is a form of dysgammaglobulinemia where the proportional levels of the IgG isotype are reduced relative to other immunoglobulin isotypes.

| IgG deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Selective deficiency of immunoglobulin G |

| |

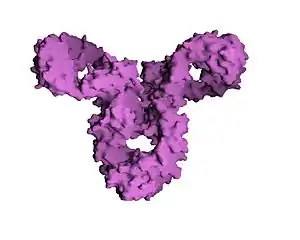

| Immunoglobulin G | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

IgG deficiency is often found in children as transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy, which may occur with or without additional decreases in IgA or IgM. IgG subclass deficiencies are also an integral component of other well-known primary immunodeficiency diseases, such as Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome and ataxia–telangiectasia.

Classification

IgG has four subclasses: IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4. It is possible to have either a global IgG deficiency, or a deficiency of one or more specific subclasses of IgG.[1][2] The main clinically relevant form of IgG deficiency is IgG2. IgG3 deficiency is not usually encountered without other concomitant immunoglobulin deficiencies, and IgG4 deficiency is very common but usually asymptomatic.[3]

IgG1 is present in the bloodstream at a percentage of about 60-70%, IgG2-20-30%, IgG3 about 5-8 %, and IgG4 1-3 %. IgG subclass deficiencies affect only IgG subclasses (usually IgG2 or IgG3), with normal total IgG and IgM immunoglobulins and other components of the immune system being at normal levels. These deficiencies can affect only one subclass or involve an association of two subclasses, such as IgG2 and IgG4. IgG deficiencies are usually not diagnosed until the age of 12. Some of the IgG levels in the blood are undetectable and have a low percentage such as IgG4, which makes it hard to determine if a deficiency is actually present. IgG subclass deficiencies are sometimes correlated with bad responses to pneumococcal polysaccharides, especially IgG2 and or IgG4 deficiency. Some of these deficiencies are also involved with pancreatitis and have been linked to IgG4 levels.

While all the IgG subclasses contain antibodies to components of many disease-causing bacteria and viruses, each subclass serves a slightly different function in protecting the body against infection.

Clinical presentation

Most of the patients do not present any symptoms of the disease; however, because IgG deficiency is often combined with any other form of selective antibodies subclass deficiency, their combination could lead to a clinically significant immunodeficiency.[3] Patients with any form of IgG subclass deficiency may occasionally suffer from recurrent respiratory infections similar to the ones seen in other antibody deficiency syndromes, chiefly infections with encapsulated bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. An increased frequency of viral upper respiratory infections may not be an indication of antibody deficiency.[4]

In healthy children, IgG2 antibodies start out low and gradually expand with age. Since IgG2 is the important component of the immune response against polysaccharides, selective IgG2 deficiency could result in recurrent infection with encapsulated bacteria.[5]

IgG4 subclass deficiency is very common, but mostly completely asymptomatic.[3]

Genetics

Since the formation of antibodies is a complicated process, containing different interaction between cells and molecules (such as T cell-B cell interaction (resulting in CD40-mediated signaling), intrinsic B-cell mechanisms (cytidine deaminase-induced DNA damage), and complex DNA repair machinery (including uracil-N-glycosylase and mismatch repair pathways)), there are many levels where malfunction could possibly result into defects in class-switch mechanisms, and therefore in antibody production decrease.[6]

No significant correlation between concrete gene mutation and the IgG deficiency was discovered; the dysfunction in the regulatory elements (such as promoter or enhancer) could be possibly responsible for the phenotype.[7] Affected could be both males and females. Recent studies show that children with a subclass deficiency in early childhood develop normal subclass levels and the ability to make antibodies to polysaccharide vaccines as they get older. However, IgG subclass deficiencies may persist in some children and adults.[4]

Diagnosis

All patients with IgG deficiency require extensive diagnostic evaluation before the patient is diagnosed with a clinically significant IgG subclass deficiency. Depending on a clinical presentation, complete blood count, test for total serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM and subclass levels of IgG) and other tests are performed. If X-linked disease is suspected, carrier detection (in which at least half of mothers are usually expected to be carriers) could be accomplished.[5] Measurement of IgG subclass levels alone is not universally recommended, because the normal levels of different IgG subclasses values may vary between individuals and by age.[4]

Treatment

Treatment is mostly aimed on treatment and prevention of infections. Frequently used are antibiotics, macrolides (as anti-inflammatory agents), mucolytics and corticosteroids. In most severe cases, the immunoglobulin replacement therapy (such as IVIG) could be considered.[8]

See also

References

- Barton JC, Bertoli LF, Acton RT (June 2003). "HLA-A and -B alleles and haplotypes in 240 index patients with common variable immunodeficiency and selective IgG subclass deficiency in central Alabama". BMC Medical Genetics. 4: 3. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-4-3. PMC 166147. PMID 12803653.

- Dhooge IJ, van Kempen MJ, Sanders LA, Rijkers GT (June 2002). "Deficient IgA and IgG2 anti-pneumococcal antibody levels and response to vaccination in otitis prone children". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 64 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(02)00068-X. PMID 12049826.

- Driessen G, van der Burg M (June 2011). "Educational paper: primary antibody deficiencies". European Journal of Pediatrics. 170 (6): 693–702. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1474-x. PMC 3098982. PMID 21544519.

- "IgG Subclass Deficiency | Immune Deficiency Foundation". primaryimmune.org. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- Dosanjh A (April 2011). "Chronic pediatric pulmonary disease and primary humoral antibody based immune disease". Respiratory Medicine. 105 (4): 511–514. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2010.11.013. PMID 21144721.

- Durandy, Anne; Kracker, Sven (2012). "Immunoglobulin class-switch recombination deficiencies". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 14 (4): 218. doi:10.1186/ar3904. ISSN 1478-6354. PMC 3580555. PMID 22894609.

- Pan Q, Hammarström L (December 2000). "Molecular basis of IgG subclass deficiency". Immunological Reviews. 178 (1): 99–110. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.17815.x. PMID 11213812. S2CID 6553947.

- Maarschalk-Ellerbroek LJ, Hoepelman IM, Ellerbroek PM (May 2011). "Immunoglobulin treatment in primary antibody deficiency" (PDF). International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 37 (5): 396–404. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.027. PMID 21276714. S2CID 31107473.