Servants' quarters

Servants' quarters are those parts of a building, traditionally in a private house, which contain the domestic offices and staff accommodation. From the late 17th century until the early 20th century, they were a common feature in many large houses. Sometimes they are an integral part of a smaller house—in the basements and attics, especially in a town house, while in larger houses they are often a purpose-built adjacent wing or block. In architectural descriptions and guidebooks of stately homes, the servants' quarters are frequently overlooked, yet they form an important piece of social history, often as interesting as the principal part of the house itself.

Origins

Before the late 17th century, servants dined, slept and worked in the main part of the house with their employers, sleeping wherever space was available. The principal reception room of a house—often known as the great hall—was completely communal regardless of hierarchy within the household. Before this period only the very grandest houses and the royal palaces such as Hampton Court, Audley End and Holdenby House, had distinct secondary areas. These areas, often courtyards known as the Kitchen of Base court, were not exclusively for the servants, and neither were they inconspicuous. At Hampton court the lesser courtyard forms part of the formal processional route under an ornate clock tower to the more grand areas of the palace. Servants before the late 17th century had a greater social standing than their 18th century counterparts. They included gentlewomen and various poorer relations of the owners, and there were also far more of them. In 1585, the Earl of Derby had a household of 115 people, while forty years later the Earl of Dorset was still maintaining a household of 111, all of whom were reported to be living in great state.[1] By 1722, the more elevated Duke of Chandos had a household of 90, 16 of whom were members of his private orchestra rather than domestic servants. The reduction in staff numbers went hand in hand with the reduction of ceremony. The formalities of presenting food to the entire gathered household in the hall with ceremonies of bowing, kissing and kneeling and cupbearers were disappearing and servants were becoming less obvious.[1]

Roger Pratt is the architect credited with pioneering the removal of servants from dining in the great hall.[2] In 1650 at Coleshill House Pratt designed the first purpose-built servants' hall in the basement. By the end of the century, the arrangement was common; the only servants left in the hall were those waiting for a summons.

By the late 17th century, the idea of giving servants their own designated areas had been adopted not only in the houses of the aristocracy, as at Coleshill, but also in those of the gentry such as Belton House. This improved privacy and kept cooking smells, noise, and any other indelicacies of the lower classes away from their more cultivated employers, thus allowing the great hall and its adjoining rooms to be more tastefully decorated and specifically employed.

It was essential that servants were close at hand, so they were given their own specific floors, usually the lowest and the highest. These floors were often, as at Belton, distinguished by a different fenestration from the rooms of the employers in between. Hence at Belton can be seen the small windows of the semi-basement containing the kitchens, pantries and servants' dining halls. Above are the large windows lighting the principal rooms, while right at the top of the house are again the small windows of the servants’ bedrooms. These rooms which were entirely in main block of the house, and constituted distinct servants' quarters, were to be the forerunner of the service wing.

While Belton was being completed, a change was taking place in architecture with more classical genres of the continental Baroque being introduced. Chatsworth House and Castle Howard are symbolic of this period. The Baroque house introduced revolutionary changes to the layout and introduction of the state apartments, and brought innovations in the lives of the staff who were now to be firmly lodged in their places downstairs.

The new Baroque fashion, and that of Palladianism which quickly followed it, swept away the double pile concept of one compact block with sets of rooms back to back as at Belton in favour of houses having at their centre a grand corps de logis flanked by long wings or pavilions, which in Palladio's original conception had been the mere farm buildings of what were small country villas. These wings became adapted in design to house the staff, and other secondary rooms.

A second distinguishing feature of this new era was that flat lead roofs often replaced the former attics where the servants had slept. This lack of space was compensated in the new houses by the entire ground floor being given over to servants. This floor, usually built of rusticated stone, was beneath the larger and grander piano nobile occupied by the employers. Ornate external staircases were built to the front door which was now clearly on the first floor. The nobility now had minimal contact with those living downstairs.

The 18th century servant

It was not uncommon for the service wings to be the same size as the main part of the house which they served, or even larger than it. At the Baroque Castle Howard and its slightly younger relation Blenheim Palace completed in 1722, the service wings are of monumental proportions, intended to be highly visible, enhancing the appearance of both the size and prestige of the mansion. In smaller houses the flanking wings could take the form of symmetrical pavilions linked to the corps de logis by open or closed colonnades. Each pavilion was a self-contained unit for a designated purpose as at both Holkham Hall and Kedleston, where one pavilion housed the kitchens and staff, and another the private family rooms. These servants wings could be fairly small compared to the overall size of the house, as the servants had at their disposal, in addition to their own wing, the ground floor of the entire building. The kitchen and its attendant odours, however, were always confined to a more remote wing.

While life upstairs away from the servants became more relaxed with less ceremony, life downstairs became a parody of the former world upstairs. Butlers, housekeepers and cooks now became monarchs in their own small kingdoms. A strict hierarchy among the servants developed which persisted in the grander households until the 20th century. The upper servants in large households often withdrew from the servants' hall to eat their dessert courses in the privacy of a steward's room in much the same way the owners of the house had withdrawn to a solar from the Great Hall in the previous era. Strict orders of precedence and deference evolved which became sacrosanct.

.jpg.webp)

During the 18th century, the only way of summoning a servant was by calling, or a handbell. This meant a servant had to remain on duty within earshot at all times (straight-backed uncomfortable hall chairs designed to keep servants awake date from this period). However, the early 19th century invention of the bell pull, a complicated system of wires and chains within ceiling and wall cavities, meant a servant could be summoned from a greater distance, and therefore also kept at a greater distance. From this time on it became fashionable for servants to be as near to invisible as possible, which fitted exactly with the next change in architectural and aesthetic fashions.

These new fashions made sweeping changes to the life of the servant. From the 1760s Palladianism was slowly superseded by Neoclassicism. A defining feature of the Neoclassical house was the absence of the first floor piano nobile. This was in part due to the picturesque values then coming into vogue. During this—the era of Humphrey Repton's idyllic landscapes—it became desirable to step from any of the main rooms directly into the landscape.[3] It was also desirable for all four sides of a house to enjoy this luxury.

Idyllic and pleasant as this concept was for those living upstairs, it was bad news for the servants, as the first and most obvious solution was to bury them. Nowhere is this more evident than at Castle Coole in Northern Ireland. The entire servant's quarters were put underground into cellars, lit only by windows at the bottom of grated pits. The only means of approach was through a single tunnel, the entrance of which was concealed by the brow of a landscaped hill some distance from the house.[4]

In the absence of electric or gas lighting the servants rooms and kitchens of this period were dark, dismal, often damp and badly ventilated places. The only advantage of Neoclassical architecture from the servants point of view, was that houses once again began to have pitched roofs, which could contain servant's bedrooms with gabled windows, albeit often hidden behind a stone balustrade or parapet. This arrangement for housing servants persisted in the affluent town houses of Britain into the late 19th century and is particularly common in the great Regency terraces of Belgravia and Mayfair designed by John Nash and later Thomas Cubitt in London.

However, in the country where there was more space, the more practical solution was to build a specific wing onto the house for the staff, and as it was often asymmetrical to the main body of the house, and of cheaper building materials, it became necessary to disguise it.

The invisible servant

The fashion for disguising the service wings led to feats of architectural engineering. In the country, where space was more available, the wings were hidden behind screens of trees, shrubs and grassy banks as at Waddesdon Manor and Mentmore Towers. While the rooms within were light and airy, the wings were often designed to have windows facing away from the principal areas of the house and its gardens. In towns where space was limited the servants fared less well, with their daytime, and sometimes sleeping, quarters in the basement.

In both town and country, means of access between the main house and the servant's wings were kept to a minimum, often the single door was lined with green baize to deaden any sound. Long and complicated passages linking kitchens with dining rooms were devised; in some houses the tortuous route through corridors and staircases from kitchen to dining room could be an eighth of a mile – an absence of cooking smells taking priority over hot food. Even the doors linking to the connecting corridors were covered by screens, sometimes disguised as bookcases with dummy books, or just simply covered in the same wallpaper as that with which the room was decorated, as the existence of servants was not to be acknowledged. Cleaning had to be performed in the early hours of the morning while the employers were asleep, and in the grander houses only male servants were allowed to be visible, and then only when required.

In some large houses from the beginning of the 19th century, enormous and ingenious efforts of building and design were employed to keep the staff out of sight. The service wings were often only accessed by tunnels as at Rockingham house and Castle Coole, both, in Ireland. At Mentmore Towers, where the service wing is a large block the same size as the mansion itself, the main part of the house is built on artificially raised ground allowing it to tower over the service wings which are in reality of a near similar height. The only windows to Mentmore's service wings were to an inner courtyard, thus preventing the servant's looking out on their employers, or their employers catching accidental sight of them. The outer, but blind, walls of the wings are of attractive dressed Ancaster stone adorned with niches and statuary, while the inner courtyard visible only to the servants is of common yellow brick. However the majority of the wing is hidden by dense planting.

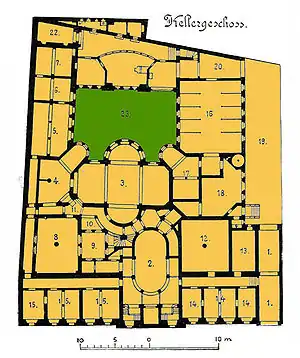

The Palais Strousberg, a vast townhouse built in Berlin between 1867–1868, confined the servants to its semi-basement. The only windows facing outwards at the front of the mansion were those of servants' bedrooms: all the workrooms either had no windows at all or were lit by a complicated system of light-wells and small internal courtyards. The servants' quarters were designed to run like a well-oiled machine. Everything from the carriage horses to the wine cellar, kitchen and laundry was confined to one compact floor under one roof and, most importantly, out of sight. Small staircases led to convenient points in a complex labyrinth of narrow passages on the piano nobile above, allowing servants to enter reception rooms when required, without being seen in other parts of the house.

King Ludwig II of Bavaria in his castles of Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee, built during the same period as the Palais Strousberg took the invisibility of his servants one step further by having designed dining room tables which were lowered through the floor to the kitchens below to be replenished between courses, negating the need for a servant's immediate presence completely. However, while the Palais Strousberg's layout of its servants' quarters was common throughout the capital cities of Europe, King Ludwig's seem to have been more an eccentricity peculiar to him. Such mechanisms had been used in 18th century "Hermitages"--small dining pavilions separate from the main house--in the Russian Empire. Examples may be seen at the suburban royal palaces of Peterhof and Tsarskoe Selo not far from St. Petersburg. This was meant to allow diners to chat freely, unencumbered by the presence of servants.

The 20th century

While staff accommodation continues to be built for hotels and similar buildings, in domestic use it has declined along with the numbers of staff kept. This major decline began in Europe following World War I. In Europe many owners of large mansions have gone so far as to demolish whole service wings. Queen Elizabeth II made this decision at Sandringham House in the 1980s, while at West Wycombe Park the roofless former service wing now contains a garden. In many other houses open to the public the former servants' domains are now restaurants, shops and offices, while the bedrooms are let to holiday makers and tourists. Where staff are retained in private houses, they are more likely to live in purpose-built apartments created from the former servants' quarters, or as at Woburn Abbey converted from former stables; at Woburn the servants' attic bedrooms have now been altered to provide more spacious bedrooms for the use of the owners, thus providing a retreat and privacy from the paying public viewing the rooms below.

Notes

- Girouard p 139

- Girouard p 136

- Jackson-Stopps p 109

- Jackson-Stopps

References

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English Country House. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02273-5.

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. Pavilion Books Ltd. ISBN 0-8021-1228-5.